The crowd is his element, as the air is that of birds and water of fishes. His passion and his profession are to become one flesh with the crowd. For the perfect flâneur, for the passionate spectator, it is an immense joy to set up house in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement, in the midst of the fugitive and the infinite. To be away from home and yet to feel oneself everywhere at home; to see the world, to be at the centre of the world, and yet to remain hidden from the world—such are a few of the slightest pleasures of those independent, passionate, impartial natures which the tongue can but clumsily define. The spectator is a prince who everywhere rejoices in his incognito. The lover of life makes the whole world his family, just like the lover of the fair sex who builds up his family from all the beautiful women that he has ever found, or that are—or are not—to be found; or the lover of pictures who lives in a magical society of dreams painted on canvas. Thus the lover of universal life enters into the crowd as though it were an immense reservoir of electrical energy. Or we might liken him to a mirror as vast as the crowd itself; or to a kaleidoscope gifted with consciousness, responding to each one of its movements and reproducing the multiplicity of life and the flickering grace of all the elements of life. He is an “I” with an insatiable appetite for the “non-I,” at every instant rendering and explaining it in pictures more living than life itself, which is always unstable and fugitive.

–Charles Baudelaire, The Painter of Modern Life (1863)1

Garry Winogrand, New York, ca. 1962. Gelatin silver print, 8 3⁄4 × 13 1⁄4 inches. Garry Winogrand Archive, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona. © The Estate of Garry Winogrand. Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

Has a more perfect description of the work of Garry Winogrand ever been penned? Re-reading Baudelaire’s mellifluous prescription afresh, the continuous arc of depictive art practices that lifts off from mid-nineteenth century European painting and crash-lands in American street photography of the mid 1960s is brought into vast, sweeping relief. The exquisite dovetailing of this famous passage and Winogrand’s practice cannot help but cast both in some sort of mutual light: Baudelaire as prophet, Winogrand as classicist. Baudelaire’s crystal ball may have been seriously cracked when it came to picking art-historical winners (The Painter of Modern Life was written about the half-forgotten painter Constantin Guys), but his poetic notion of an art of urban observation that fuses nature and the imagination, the individual and society, the fugitive and eternal, kept artists and scholars busy for well over a century, ultimately succeeding in redefining Romanticism in terms of the fleeting impressions of the modern metropolis.

The stunning retrospective of Winogrand’s work currently up at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art,2 affirms that it was Winogrand, more than any of his cohort,3 who glimpsed and executed the endgame of this redefinition. Winogrand defined a new poetics of alertness to public space that prized the intuitive, the underdetermined, and the as-yet-unknown. It’s an anxious, giddy, widely varied body of work, in which the careful balance between the “ephemeral” and the “eternal” that Baudelaire esteemed is brazenly tipped toward a pure poetics of the fleeting individual glance. By rendering the most pointed and the most passing of human gazes equally permanent, or “eternal,” through the fixed medium of photography, as no one had ever really done before, Winogrand’s art forced a serious recalibration of the meaning and scope of these hoary but omnipresent terms.

Baudelaire, of course, hated photography, seeing in it the corruption of the imagination, and the subjugation of the individual to mass society. But he also valorized the inexpensive, quickly produced sketch, which could keep pace with the artist’s impulsive perceptions as he navigated the thrill of the throng. (Reading across Baudelaire’s writings, it is hard not to suspect that his hatred of photography conceals, in the fashion of the stories of Edgar Allan Poe, something like lust.) To the quizzical reader, Baudelaire’s famous paragraph quoted above baits some difficult questions: Does the spectator-prince abandon his own family in his embrace of the whole world as family? Do the powers of the lover who draws from the electricity of the crowd go into remission when the crowd’s energy is gone? Does insatiable spectatorship ever interfere with the flâneur’s ability to truly participate in life? These questions are the demonic underside of the cult of the spectator, writ large in the obsessions of popular photography. They constitute a moral calling-to-account to which the questioning moralist may never hear a fully satisfying reply, and all of these implicit criticisms can be leveled brutally at Winogrand, whose personal life can read like a litany of major irresponsibilities and minor catastrophes. Aesthetically speaking, the force of these queries isn’t so much a flaw with the work as it is an indication of its immense scope, which charts the pleasures and terrors of flâneurdom with an almost morbid depth.

Winogrand adored still photography with the devotion of an absolute addict, apparently hooked for life from the moment he first stepped into a college darkroom. (He soon dropped out.) He quickly mastered the techniques of the staged advertising photo and found steady commercial work through the 1950s. In the exhibition, a lone magazine advertisement in a vitrine suffices to show his full command of the staged photo-illustration, bounce-lit and perfectly printed. Perhaps by virtue of his very facility, he came to be repulsed by the obviousness of advertising’s messaging. It was more challenging, and more thrilling, to produce an unplanned image, one that directly analogized the accelerated, modern experience of the still photograph to the theater of snap-judgments that occur when strangers meet in public space. Winogrand’s exploitation of the handheld camera and the sensitivity of high speed film are utterly historically contingent on the technical breakthroughs of the previous era, but the material foundations of his craft should not be confused with its method, which is predicated on a radical lack of preconception, a surrender to circumstance that runs profoundly contrary to most theories of creative authorship.

Some pictures are triumphantly simple. The strolling lady and gentleman in New York (1962) are on top of the world, crowned with sunshine, and flush with the pleasures of material comforts. It’s an unfussy, ebullient picture of the postwar American boom, of capitalism gone right. I think of this couple (who grace the cover of the exhibition’s catalog) as the loose counterpart to the middle class couple in Gustave Caillebotte’s Paris Street, Rainy Day (1877). In juxtaposition, the photographic focus effects of the Caillebotte and the faintly painterly composition of the Winogrand, both in the service of a passing pedestrian glance, chart a deep but fractured historical symmetry whose details could easily fill a book.

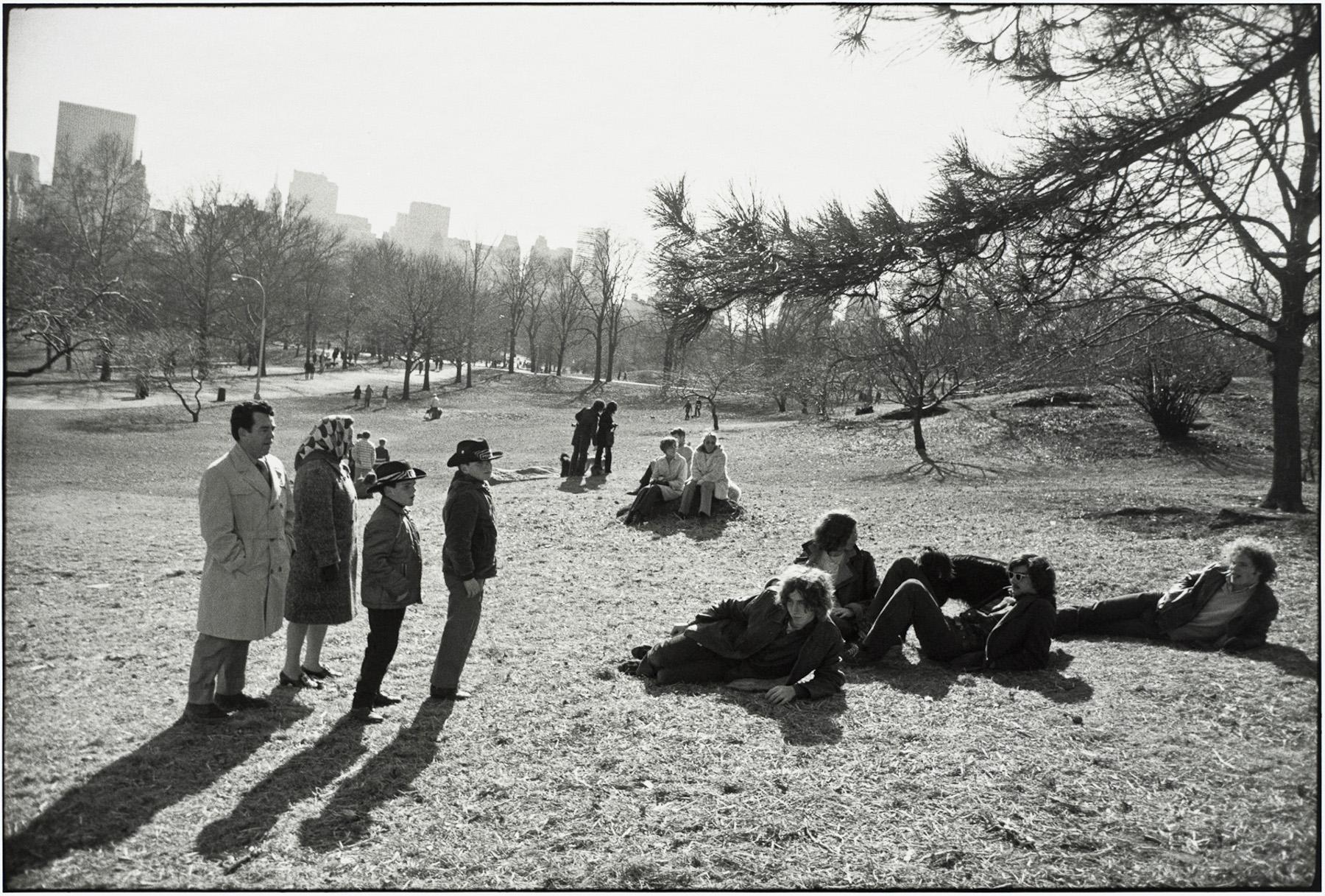

Garry Winogrand, Central Park, New York, 1969. Gelatin silver print, 8 3⁄4 × 13 1⁄4 inches. Collection SFMOMA, purchase through a gift of Mark McCain and Caro Macdonald. © The Estate of Garry Winogrand.

Other pictures work on a principle of ironic juxtaposition. In a later picture,4 a conventional nuclear family (possibly tourists) visiting Central Park closely approaches a loose group of hippies lounging on the grass. The humor of the picture has something to do with the directness of the family’s befuddled stares, and the affected swagger of the hippies, who refuse to return that stare directly. This picture has a strange ambiguity of scale, owing to the small stature of the family and the exaggeratedly long shadows thrown by the late afternoon sun. Everything in the picture feels either slightly too large or slightly too small, in the manner of a painting unconcerned with perspective. It’s always reminded me of Manet’s On the Beach at Boulogne (1869), with its flattened distribution of figures and open landscape setting, promising endless permutations of social interchange. But in Winogrand’s image, that metaphoric interchange is hilariously disrupted; the viewer is presented with a social chasm that won’t be crossed.

Such scenes of straightforward ironic difference, however, are generally few and far between. More commonly, Winogrand looked to the play of manners recorded by the photographic encounter itself, as when he cornered a group of men in an elevator, or recorded the faces of passersby in the street, often cropping their bodies disruptively. His signature approach of the 1960s quickly became a recognizable stylistic template: a wide angle shot stuffed with the incongruous faces, gestures, and reactions of New Yorkers in public space. Like Diane Arbus, he was attracted to images in which a person’s managed self-presentation can be seen to break down. But unlike Arbus, he didn’t make a business of fetishizing people’s abnormalities. He is sometimes compared to Weegee, but this comparison mainly serves to highlight their obvious differences: Weegee’s attraction to shocking, graphic subjects and Winogrand’s preference for the surreality of the everyday.

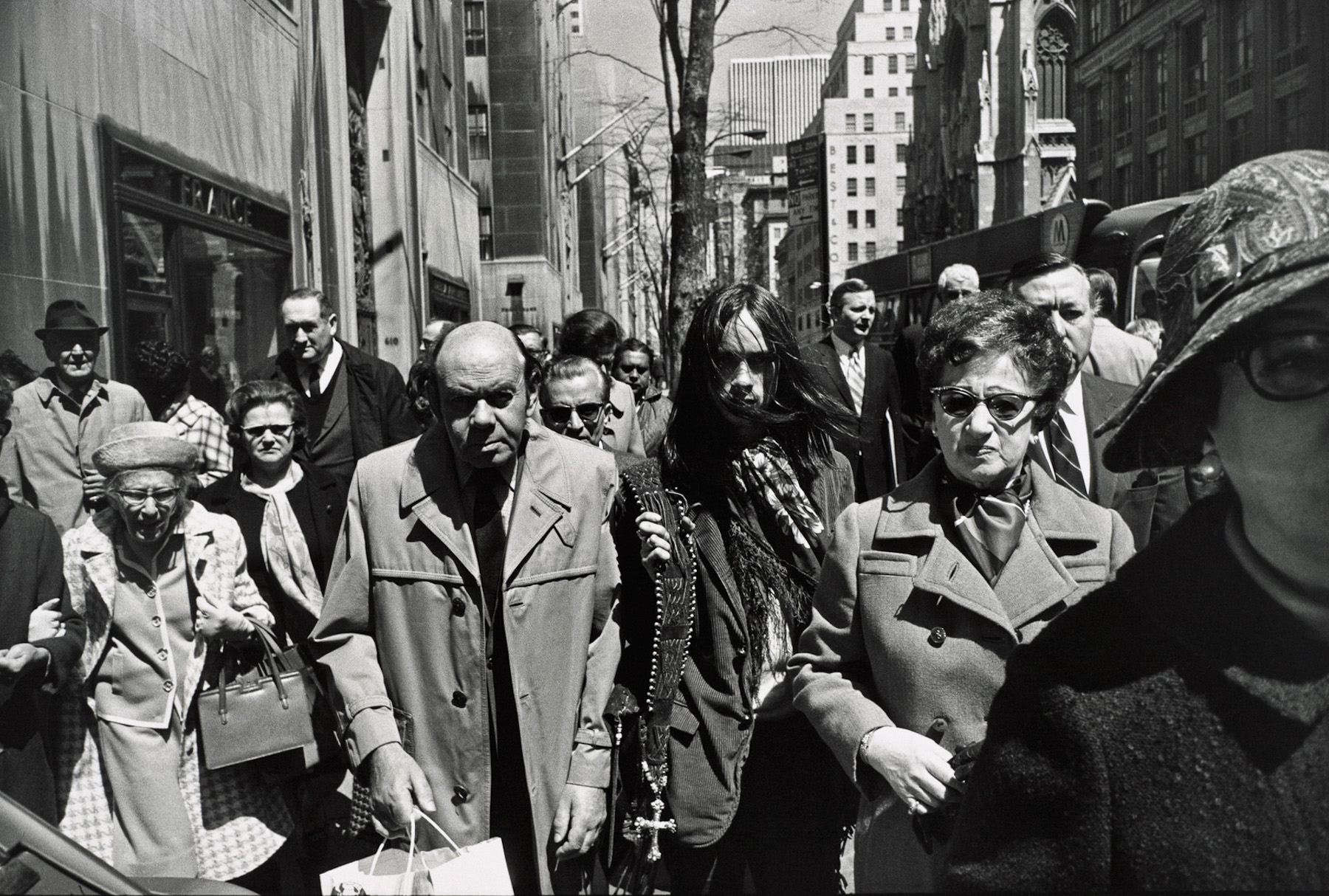

Garry Winogrand, New York, 1970. Gelatin silver print, 8 3⁄4 × 13 1⁄4 inches. Collection of Randi and Bob Fisher. © The Estate of Garry Winogrand. Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

Motion is the only rule, a jostling, headlong stride across the street. He doesn’t look for turning points in the actions or gestures—everything is captured mid-stride, with a brusqueness bordering on belligerence. Friends who knew him have described an act that he would do when shooting in public, checking and double-checking his camera, pretending that something was wrong with it, something that needed fixing, while all the while making exposures and advancing the film. This silent patter, this “game” of playing the fumbling amateur no doubt evolved as a way of remaining unobtrusive and avoiding direct confrontation with his subjects.

The photographic literature of Winogrand’s lifetime is deeply marked by the writing of John Szarkowski, the Museum of Modern Art curator and self-described “game warden” who nurtured Winogrand’s professional career, proclaiming him “the central figure” of his generation. Szarkowski’s early writings establish a photographic essentialism, a theory of the photographic that is unmistakably indebted to Clement Greenberg’s essentialist theories of painting and sculpture. But while Greenberg, who wrote almost nothing on photography, hewed almost exclusively to painting’s formal properties (its flatness, its shape), Szarkowski drew upon the cultural “essences” of photography (the amateur snapshot, the travelogue, the anonymous image). From these observations he produced a compelling argument for the importance of Winogrand by virtue of his central engagement with ordinary subjects, public space, and conventional tools.(This didn’t go over well with everyone. Beaumont Newhall, Szarkowski’s predecessor at MOMA, stormed out of a Winogrand talk after standing up to exclaim “But they’re just snapshots!”) Part of the thrill of these pictures, then and now, is in just how closely they tread to bad photojournalism, and how roughly their simple low-contrast printmaking style defies the mannered niceties of the darkroom-embellished “fine” print. In this “preference for the primitive,” to borrow Ernst Gombrich’s phrase, they reproduce and extend a midcentury taste for the familiar rendered difficult. “He’s not afraid to look ugly,” Greenberg once wrote admiringly of Pollock, and the same could be said of Winogrand. To his even greater credit, Winogrand’s not afraid to look funny.

Winogrand, borne into the art-world firmament partly on the wings of this photographic essentialism, appears to have adopted it wholesale as his own. His marvelously quotable epigrams manifest a distrust bordering on nihilism:

“I don’t have anything to say in any picture.”

“My only interest in photographing is photography.”

“A photograph is an illusion of a literal description of how the camera saw. …From it, you can know very little. It has no narrative ability. You don’t know what happened.”

“The photograph is its own reality. Come right down to it, once it exists, it has no relation to what was photographed.”

“The thing that’s intriguing is not really knowing what the result is going to be like.”

“Generally, I probably take every picture just to see what something looks like photographed. Why I aim at particular things I haven’t the vaguest idea. That you gotta lay down on a couch for.”

“I really don’t have an imagination.”

“That work is not discussable as photographs, period.” [speaking of Jerry Uelsmann’s photomontages]5

Today, as many have insisted, the myth that photographs tell the truth has been replaced by the myth that they tell lies,6 and Winogrand’s brilliantly pithy pronouncements should be seen as both symptoms and agents of this reversal, far in advance of any digital “revolution.” But how did someone whose work is so full of accident, humor, and unresolved chaos come to espouse a notion of photography that is so reductive, formally ironic, and narrowly mediumistic? Part of the answer is surely generational: Winogrand came of age at a moment when the Life magazine-style photo narrative was the dominant model of production, and resisting that model required a rigid, even hyperbolic rhetorical stance. The prestige of Szarkowski’s influential exhibitions, too, must be recognized as giving Winogrand the license to refrain from explaining his work in the way that artists are customarily expected to today. Lastly, Susan Sontag’s essays on photography from the late 1960s must be counted as a major influence. Sontag, approaching photography from a fundamentally literary perspective, dismantled humanistic claims for photography’s benevolence with an unprecedented ferocity. (It was Sontag, too, who drew the historical connection between the flâneur and the street photographer.)7 Winogrand read Sontag, and took note, even directing his students to read her book Against Interpretation (1966) as a guide to understanding his own work.8

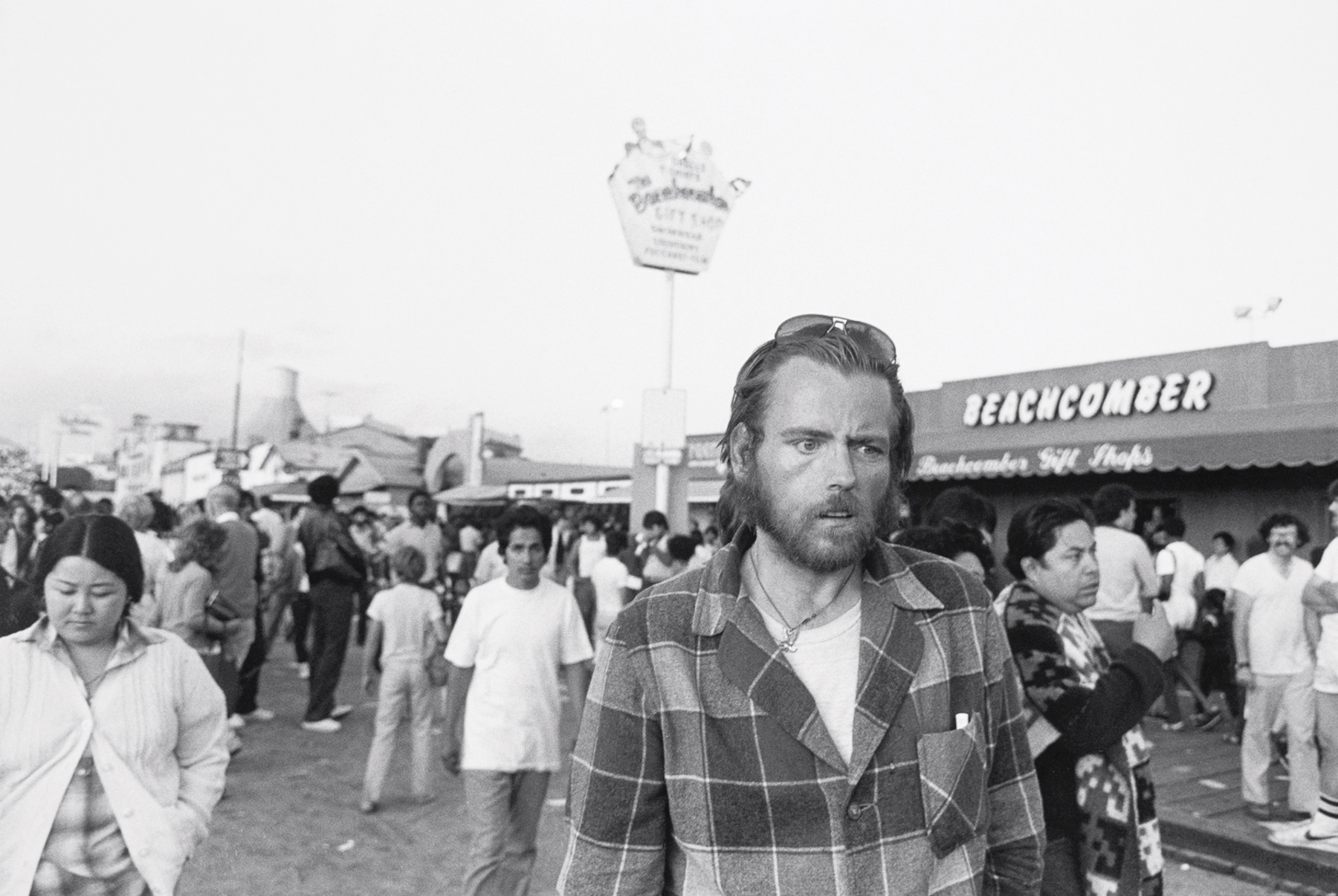

Garry Winogrand, Los Angeles, 1969. Gelatin silver print, 8 3⁄4 × 13 1⁄4 inches. Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. © The Estate of Garry Winogrand. Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

Back in the galleries, Winogrand’s cheekily dogmatic materialism comes across as something of a ruse. Today, many artists make work that is more belligerent, more invasive, or more nihilistic. In hindsight, Winogrand’s earnest attachment to his subjects, to people, seems much clearer. If anything, his deep philosophical pessimism makes his authentic love of actual human beings all the more striking. Today, we accept that the narrative content of a still photograph is fragmentary and limited, but we can safely insist that all content has a narrative dimension. His photographs’ true subject, in a sense, is the contestation (a favorite word of his) between content and form that they enact. Winogrand’s formalism was ultimately just a straw man that the eccentricities of his subject matter could set ablaze.

When he died of cancer in 1984, Winogrand left behind 2,500 rolls of exposed but undeveloped film, 4,100 rolls that he had processed but not contact printed, and 3,000 contact prints that seem to have been barely examined. Much of this film was shot in Los Angeles, where he moved in 1979. Some money was found to develop the film, and a selection of images were shown at the Museum of Modern Art in 1988. But only recently has the work been fully reviewed, this time by a team including photographer Leo Rubinfien, Erin O’Toole from SFMOMA, and Sarah Greenough from the National Gallery of Art. The endpapers of the exhibition’s catalog are handsome enlargements of vintage contact sheets, annotated with the photographer’s signature scribbles, two small red circles on each image that appears to have been “of interest.” There are other telltale marks too: boxes drawn around certain frames, and smaller rectangles within the frame whose meaning isn’t entirely clear; this mental map has no precise legend.

Garry Winogrand, Los Angeles, 1980–83. Posthumous digital reproduction from original negative, 8 3⁄4 x 13 1⁄4 inches. © The Estate of Garry Winogrand. Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

Following Szarkowski, who was dismissive of the late work, many have argued that Winogrand, in his later years, was simply out of control, shooting with obsessive abandon, and had lost the ability to meaningfully edit his work. Evidence for this viewpoint comes from the relatively high percentage of dismally boring pictures from the later contact sheets. Others suggest, more generously, that Winogrand was simply more interested in shooting than in printing, and that this preference can be seen as a positive philosophical preference for process over product, action over stasis, becoming over being. A third possibility is that Winogrand simply preferred to “age” his photographs so that he could evaluate them objectively, his judgment unclouded by the profound enjoyment he clearly took in the shooting process. There is ample precedent for this approach in the production methods of the magazine work that Winogrand cut his teeth on, a process in which editing was typically performed by someone other than the photographer. Each of these three explanations clearly has a role to play in explaining the mess that Winogrand left behind, but none of them clears the ethical minefield that any curator faces in editing, indeed arguably completing, a late artist’s unfinished work. The curators realize the issue fully, to their credit, and take care to annotate the provenance of each print in minute detail, correctly choosing to describe the problem rather than try to solve it. The problem is that, even in simply deciding to print and frame the later work in the same general fashion that the early work was displayed, the exhibition’s organizers run the risk of insisting on a false continuity.

Garry Winogrand, Santa Monica Pier, 1980–83. Posthumous digital reproduction from original negative, 8 3⁄4 × 13 1⁄4 inches. © The Estate of Garry Winogrand. Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

Moving to Los Angeles, Winogrand had to have sensed that his principal formal model, the wide angle New York street view packed with incident and shot close-at-hand, would not transfer intact to the wide, relatively pedestrian-free boulevards of Los Angeles in the 1970s. His earlier photographs taken on visits to Los Angeles had essentially been one-shots. For example, his snarky 1964 photograph of a boy in Mickey Mouse ears traipsing across Forest Lawn cemetery was apparently a hit in New York, where it was printed large and hung high on the wall in Szarkowski’s 1967 New Documents show. A few pictures sustain the specific effect of the earlier work, but Winogrand seems to have struggled to realize a new way of working that was idiomatic to Los Angeles. There are a few photographs of celebrities (Drew Barrymore, Art Laboe) with his distinctive peculiar framing. There are the images of beautiful women, always a staple of his oeuvre, though fewer in number and less ebullient. Several powerful images depict desperate-looking individuals surrounded by open space—portraits, really, of damaged-looking strangers caught off-guard, or sometimes on-guard. And then there are endless contact sheets from this period, all taken from the window of a car, in which the distance from the human subject of the image yawns into a dull chasm. These sequences have their own poetics of desolation and wandering, but they are so far afield from the single-image geometries of the early work that one is simply left wondering what Winogrand himself would have made of them had he lived a little longer. Like the film director in Wim Wenders’s The State of Things (1982), or the photographer in Jacques Demy’s The Model Shop (1969), he appears to have genuinely gotten lost in the city’s endless thoroughfares, a romantic vision well charted by cinema, perhaps even a part of his decision to relocate there.

One of these car shots, of an inscrutable figure collapsed in the street (also reproduced prominently on the rear of the catalog’s dust-jacket) occasions this wall text:

This photograph of a woman collapsed in the parking lane of Sunset Boulevard is one of four consecutive frames that Winogrand exposed one afternoon not long before the end of his life. In his earlier pictures of the injured and the fallen a primary element was the sense of his own unsatisfied curiosity, his straining to understand what was happening. Here, though, the dominant note is speed—that of Winogrand’s movement, and that of the sleek Porsche Carrera roaring out ahead of him. Here death is presented as a brutal, irredeemable force, while life is shown to rush by so fast that we have little chance of comprehending it at all.

Garry Winogrand, Los Angeles, 1980–83. Posthumous digital reproduction from original negative, 8 3⁄4 × 13 1⁄4 inches. Garry Winogrand Archive, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona. © The Estate of Garry Winogrand. Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

It is flat-out impossible to accept that an artist who pointed to Against Interpretation as the key to his work could possibly have countenanced this sort of writing. The problem, of course, is that Sontag’s demand that we renounce interpretation is equally impossible to satisfy. Given the centrality of intention to art discourse, how do we not interpret? While the image is basically an artistic flop, it’s a flop by such a great, skewed talent that it can’t help but take on a certain metaphoric weight when presented on the museum wall, especially alongside this text. While it has always been true in some sense that images are “produced” in “collaboration” between the artist and viewer (the old post-structuralist saw), this image seems more to have been produced mainly by a garbled authorial voice that is more Rubinfien than Winogrand. The potential of a photograph to capture an object or quality that the photographer himself was unaware of, what Walter Benjamin famously termed “the optical unconscious,” is showcased here to uncomfortable extremes, made all the more problematic by this particular image’s origin on an unmarked, possibly unviewed contact sheet. The rights of the dead are continually being compromised, or at least ventriloquized through the living. But the vexed status of this quietly haunting image, the optical unconscious in extremis, pointedly asks us anew: whose unconscious is it, anyway?

Benjamin Lord is an artist based in Los Angeles.