Francis Alÿs: Politics of Rehearsal offers a comprehensive view of the work of an artist widely considered one of the most important working today. Most of the work presented is either video distilled from filmed events enacted in real time, or video art that plays with the illusion of having been edited from a continuum. Curator Russell Ferguson’s strategy for dealing with this challenging material is to define how each piece represents a facet of Alÿs’ work, offering, along with the artists’ notes and sketches, examples of like or related pieces in the artist’s oeuvre. Despite the carefully written and selected documentation, the show feels a bit empty at first, as if it is about an elusive idea of art rather than art objects. If one reads all the supporting material and watches each video in entirety, however, this feeling dissipates and is simultaneously understood as an effect and end of Alÿs’ unique art practice.

Prescient as this work is, in its form and content it is also reminiscent of 1960s and ‘70s event and performance art. In the show’s documentation, Alÿs refers to predecessors such as Smithson and Long, explaining his own work as an attempt to “de-romanticize” theirs and recast it as “social allegory.” Elsewhere he refers to Chris Burden as a model. Curiously, however, neither in the show’s documentation nor in published interviews does Alÿs refer to Allan Kaprow, the artist to whom he would seem most indebted. The unintentional synchrony of Alÿs’ first major U.S. show and Kaprow’s first international retrospective appearing in Los Angeles during the same year illuminates the degree to which Alÿs’ work is built on the challenge that Kaprow made to the boundary between art and life. It is, as it were, a re-rehearsal of that challenge, now adapted to art institutions and the market, but with an explicit new focus on politics.

Anyone familiar with Allan Kaprow’s work will find in the work of Francis Alÿs echoes, variations, and provocative recombinations of Kaprow’s metaphorical Happenings and Activities. Paradox of Praxis I(1997) in which Alÿs pushed a block of ice through the streets of Mexico City, recalls, for example, Kaprow’s Drag (1984) where participants pushed or pulled a single concrete block around the UCSD campus, but also Fluids (1967), where Kaprow and others used large blocks of ice to construct enclosures throughout Los Angeles.

Alÿs’ When Faith Moves Mountains (2002) enlisted hundreds of volunteers to displace a huge sand dune a fraction of an inch. Kaprow’s Purpose (1969) did something similar on a smaller scale: “Making a mountain of sand/ moving it repeatedly/ until there is no mountain…”1 Various other Kaprow Happenings required collective effort to move water or dirt, as in Course (1969): “Digging tributaries to river/ Bucketing out the water/ Carrying it upstream to first tributary/ Pouring it back in/ Bucketing out that water/ Carrying it upstream to next tributary/ Pouring it back in/ And so on, till no more tributaries/ Telling the world about it….”2

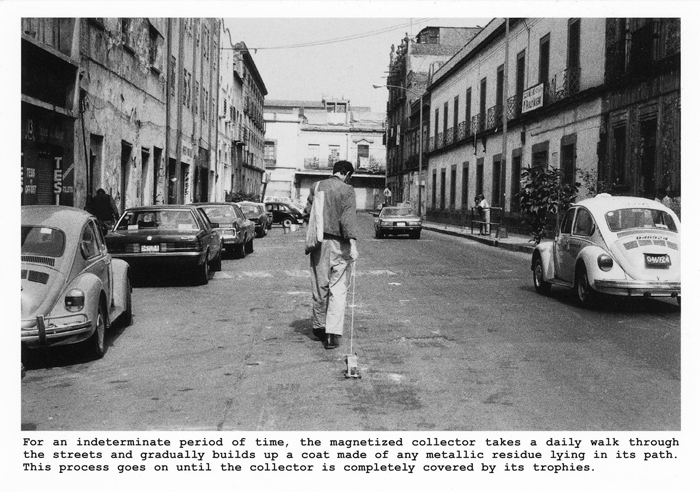

Francis Alÿs, The Collector, 1990-1992. Postcard. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York.

Allan Kaprow, Taking a Shoe for a Walk, 1989, Activity. Photo: Wolfgang Traeger. Courtesy of Wolfgang Traeger. Copyright / All Rights Reserved by Wolfgang Traeger, Germany.

A signature Alÿs piece is The Collector (1990-1992), where he pulled a little magnetized wooden dog on wheels by a string around Mexico City. In a related 1994 piece, Alÿs walked around Havana in magnetic shoes to see what would attach to them. Presented less than a year before The Collector, Kaprow’s Taking a Shoe for a Walk (1989) asked participants to select an old shoe, tie a string to it, and pull it through the streets of Bonn, periodically repairing the shoe with bandages. Nearly twenty years earlier, Kaprow’s Round Trip (1968) involved rolling a ball of paper garbage tied with string through city streets, collecting more garbage to it until it became a huge ball, then gradually stripping down the ball to nothing.

Countless more comparisons could be made, and similarities are not limited to objects used or actions undertaken. There is the absurdity of a simple gesture repeated again and again; the mirroring of the gestures of another; the aspect of the unfinished, or in-process work; the value placed on useless work; the importance of communal effort. Yet there is one apparent difference: Alÿs’ designation of his work as political. The exhibition’s very title, Politics of Rehearsal, is unlike any title in Kaprow’s oeuvre.

The title sets an expectation that politics will be central to this exhibition, but it also presents a riddle. Is the emphasis on politics or on rehearsal? And what does one have to do with the other? This quickly becomes clear in Alÿs’ title piece, a single monitor video in which the concept of development, both with regard to creative process and economic growth, is contrasted with the concept of rehearsal and found to be a retrograde, goal-oriented idea infused with imperialist implications. While reminiscent of surrealist film with flashes of Truffaut and Ophuls, politics is very much on the surface of this coolly witty piece. Beginning with the rehearsal of a dancer, singer and pianist, it cuts to documentary footage of President Truman’s 1949 inaugural address, then returns to the rehearsal. We hear Alÿs’ and Cuauhtémoc Medina’s “voiceover” discussion of U.S. policy of development in Latin America while the dancer does a strip tease exemplifying the enticements and frustrations of this ideology.

The playful collision of development and rehearsal continues throughout the exhibition, but in no other work is politics explicit. Other pieces, such as the one involving the efforts of a VW to make it to the top of a hill or of a boy to kick a bottle to the top of an inclined street, are defined as political parables in the exhibition documentation only. One wonders what the effect would be without the didactics. Certainly there would be more focus on the experience of frustration that leads to helpless laughter, after which various possible meanings come to mind about effort and achievement, creativity and the everyday, and last of all, mainly because of the setting, politics and poverty.

Alÿs’ political intentions expressed in the course of the exhibition are more fully articulated in interview fragments cited in the catalog essay. Alÿs comments, for example, on the impact his adopted city has on his work: “I think being based in Mexico City, and functioning in Latin America or other places where you find yourself confronted with ongoing economic, social, political, or military conflicts, the political component is an obligatory ingredient in addressing these situations.”3 Concerned with creating a politically significant art “without assuming a doctrinaire standpoint or aspiring to become social activism,”4 Alÿs believes resistance lies in the anecdotal. The idea is to insert a provocative action into a politically charged environment and allow it to attract meanings, like the magnetic dog. The artist may then point out these meanings, or preserve them by encouraging his actions to become anecdotal and thus a part of legend.

Though Kaprow worked in the “developed” U.S., a major portion of his work was created in a time of political upheaval. Even though they remained apart in a kind of parallel universe of the art world, his Happenings and Environments belong to a culture of political marches, sit-ins, and guerrilla theater. As Kaprow commented in an interview with Barbara Berman in 1967:

When I’ve been asked to prepare Happenings for this or that political function, peace movement or protest, I have said no in all but one case (and that was a fiasco). I felt that to the extent my work was politically useful as a tool, it would be bad as a Happening. The more the end was literally a kind of reward, that is, the achieving of a political goal, the less the work would have the broader philosophical implications I’m interested in. So you might say that my work is not strictly topical, although its materials are topical. 5

Kaprow’s Happenings of the early to mid 1960s, such as Service for the Dead (1962), Courtyard (1962), Chicken (1962), Bon Marche (1963), Household (1964), or Calling (1965), bear little comparison to Alÿs’ Politics of Rehearsal (2005-07) and Rehearsal 2 (2001) despite their elaborate (if plotless) scripting, music, nudity, and simultaneous or overlapping action. In contrast to Alÿs’ perfectly edited videos, Kaprow’s sprawling Happenings deal with archetypal human behaviors—scapegoating, sacrifice, and objectification—with roots in ancient ritual. These behaviors are still operative, the work suggests, in contemporary urban crime and other symptoms of social and economic disparity.6

Such ideas are never explicitly stated in Kaprow’s world; rather they remain suggestions embedded in location (the courtyard of a seedy hotel or a garbage dump) or action (wrapping people in laundry bags and tossing them in trashcans). Kaprow’s notes, written either for himself or for Pre-Happening presentation to participants, sometimes did provide the symbolism or allegory of a piece, but these explanations remained secondary to experience. Dumping others and being dumped in trashcans was meant to be transformative, an effect that post-Happening discussions presumably sharpened.

In the late 1960s, Kaprow began creating Happenings with the theme of labor. Pieces like Runner (1968), Transfer (1968), Record (1968), Fluids (1967), and Roundtrip (1968) refer to the work of bricklayers, carpenters, truckers, or stonecutters. The scores for these are spare and deliberately oblique: “Breaking big rocks/ Photographing them/ silvering Big Rocks/ photographing them/ scattering the photo/ with no explanation.”7 “With no explanation” became a key part of Kaprow’s Happenings during this period; the piece should remain an unexplained riddle. Nonetheless, Kaprow’s notes contain elaborate articulations of both the form and content of these pieces. Regarding Runner, for example, in which concrete rocks were equidistantly placed on a long strip of tarpaper, Kaprow writes: “Work as philosophical, not instrumental. Rather than being social criticism, social insight. The more active it is, the more reflective it becomes.”8 That is, the more repetitious and seemingly useless the work of the Happening, the more it becomes a means for reflection or social insight.

Francis Alÿs, Paradox of Praxis 1 (Sometimes Making Something Leads to Nothing), 1997. Videostill. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York.

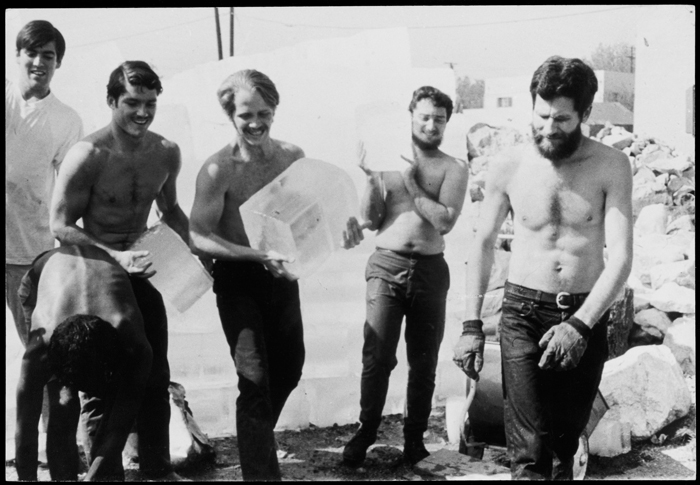

Allan Kaprow, Fluids, 1967. Photo Courtesy of Bruce Breland.

Alÿs’ repetitious activities and the videos he makes from them are amusing, even delightful, celebrations of nonproductive work. But they also provide a means for reflection. His defiant “sometimes making something leads to nothing,” which flashes on the screen at the end of Paradox of Praxis I (1997) is emphatically paradoxical: though the ice has melted and thus the work no longer exists, it has created an experience that is something— not to mention a video. This paradox, central to the creative act, where the notion of an end or goal stifles a work’s internal unfolding, is not the only stated meaning of Praxis. Alÿs designates this work as a parable about Minimalism and a generational working through of its legacy. Perhaps coincidentally, Kaprow’s pointedly ephemeral Fluids (1967) was seen as a reply to Minimalism as well: “During three days, about twenty rectangular enclosures of ice blocks (measuring about 30 feet long, 10 wide and 8 high) are built throughout the city. Their walls are unbroken. They are left to melt.”910

Allan Kaprow, Sweet Wall, 1970, Activity. Photo by Dick Higgins. Courtesy of Hannah Higgins.

In 1970, in the vicinity of the Berlin Wall, Kaprow built a wall of concrete blocks held together with white bread and jam instead of cement. When Sweet Wall (1970) was complete, Kaprow and others knocked it down. In a 2004 piece completely different in its form from Kaprow’s, Alÿs walked along the boundary line that separates East and West Jerusalem, carrying a can of green paint that leaked and thereby created a literal green line in reference to the one that commonly exists in political maps of the zone. Though Alÿs’ Sometimes Doing Something Poetic Can Become Something Political and Sometimes Doing Something Political Can Become Poetic is the more elegant piece, and Kaprow’s the more comic, both are interventions into a foreign, polarized context where a political boundary becomes an object of play. The difference between them, apart from the participatory nature of Sweet Wall, lies in the artists’ statements. Of Sometimes Doing Something, Alÿs says: “I had reached a point where I could no longer hide behind the ambiguity of metaphors or poetic license. It created a personal need to confront a situation I might have dealt with obliquely in the past.”11 Kaprow articulated his view of Sweet Wall in the activity booklet for the piece from 1976:

“Sweet Wall,” looking back six years, contains ironical politics. It is a parody. It is for a small group of colleagues who can appreciate the humor and sadness of political life. It is for those who cannot rest politically indifferent, but who know that for every political solution there are at least ten new problems.

…As parody, “Sweet Wall” was about an idea of a wall. The Berlin Wall was an idea too: it summed up in one medieval image the ideological division of Europe. But it also directly affected the lives of more than three million residents, at least six governments, as well as countless non-Berliners who at one time or another would be involved in that city.

As an idea for a handful of people, “Sweet Wall” could be played in the mind without serious consequences at the time. Like the wall with its bread and jam, symbols could be produced and erased at will.

The participants could speculate on the practical value of such freedom, to themselves and to others. That was its sweetness and its irony. 12

Francis Alÿs, SOMETIMES DOING SOMETHING POETIC CAN BECOME POLITICAL AND SOMETIMES DOING SOMETHING POLITICAL CAN BECOME POETIC, 2004. Jerusalem video projection; 17:45 minutes. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York.

Knowing whether or not Kaprow has influenced Alÿs is less pertinent than understanding the way Kaprow’s invented form, the Happening, has evolved through the past fifty years. A comparison of the two artists’ statements may suggest how the form has changed with regard to the word “political.” Where Alÿs regards his intervention as an assertive political act, a refusal “to hide behind the ambiguity of metaphor or poetic license,” Kaprow regarded his piece as “parody” and something to be “played in the mind.” One wonders if the change in language is a result of a political context so quietistic that what would have once been considered playful is now confrontational. Alternatively, perhaps Alÿs’ claim for the politics of his art is an ingenious way of making it a political tool without reducing it as art, a way now open to artists of his generation.

Annette Leddy is a writer who works at the Getty Research Institute, where she cataloged the Allan Kaprow Papers and collaborated on the book Allan Kaprow: Art as Life (2008).