Ottmar Hörl, Euro-Skulptur, 2001. Steel, acrylic glass, LED lights, 46 ft. Photo: Christoph F. Siekermann, Creative Commons.

The distance between Frankfurt am Main’s train station and the TowerMMK, an exhibition space under the aegis of the Museum für Moderne Kunst (MMK), is lined with drugstore chains, an Indian grocery store, a bakery famous for its cinnamon rolls, an old-fashioned gelateria. This distillation of urban Germany ends abruptly in a park where the city walls used to be. No longer marked by gates, the threshold into Frankfurt’s inner circle is still perceptible as a psycho-geographical shift: here, the shiny surfaces of glass and steel high rises reach into the sky, tantalizing concrete-bound walkers with the dream of a lofty corner office. A monumental Euro sign rises up from the lawn; twelve stars flock to its core.1 According to the website of the European Union, this constellation symbolizes unity, harmony, perfection—a clue to how the EU presents itself to citizens and non-citizens alike: a safe haven, a steady investment, an age-old guarantor of reason, and a locus of balance, even if the world is out of joint.2

Balance and the distribution of weight subtend the conceptual, aesthetic, and political stakes of Amt 45 i, Cameron Rowland’s solo exhibition at TowerMMK.3 Over the past decade, Rowland has made a name for themselves as an astute and conceptually rigorous investigator of the links between property, accumulation, and race as they are operative, for example, within the US prison system (in their 2016 show 91020000 at Artists Space, New York) and the real estate market (D37, on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, in 2018–19). In Frankfurt, Rowland presents visitors with a constellation of objects, an essay, and a contract between Bankrott Inc., a company formed for this purpose, and MMK.4 Together, these components of Amt 45 i materially manifest the violence of slavery upon which Frankfurt’s status as a financial capital and Germany’s wealth rest.

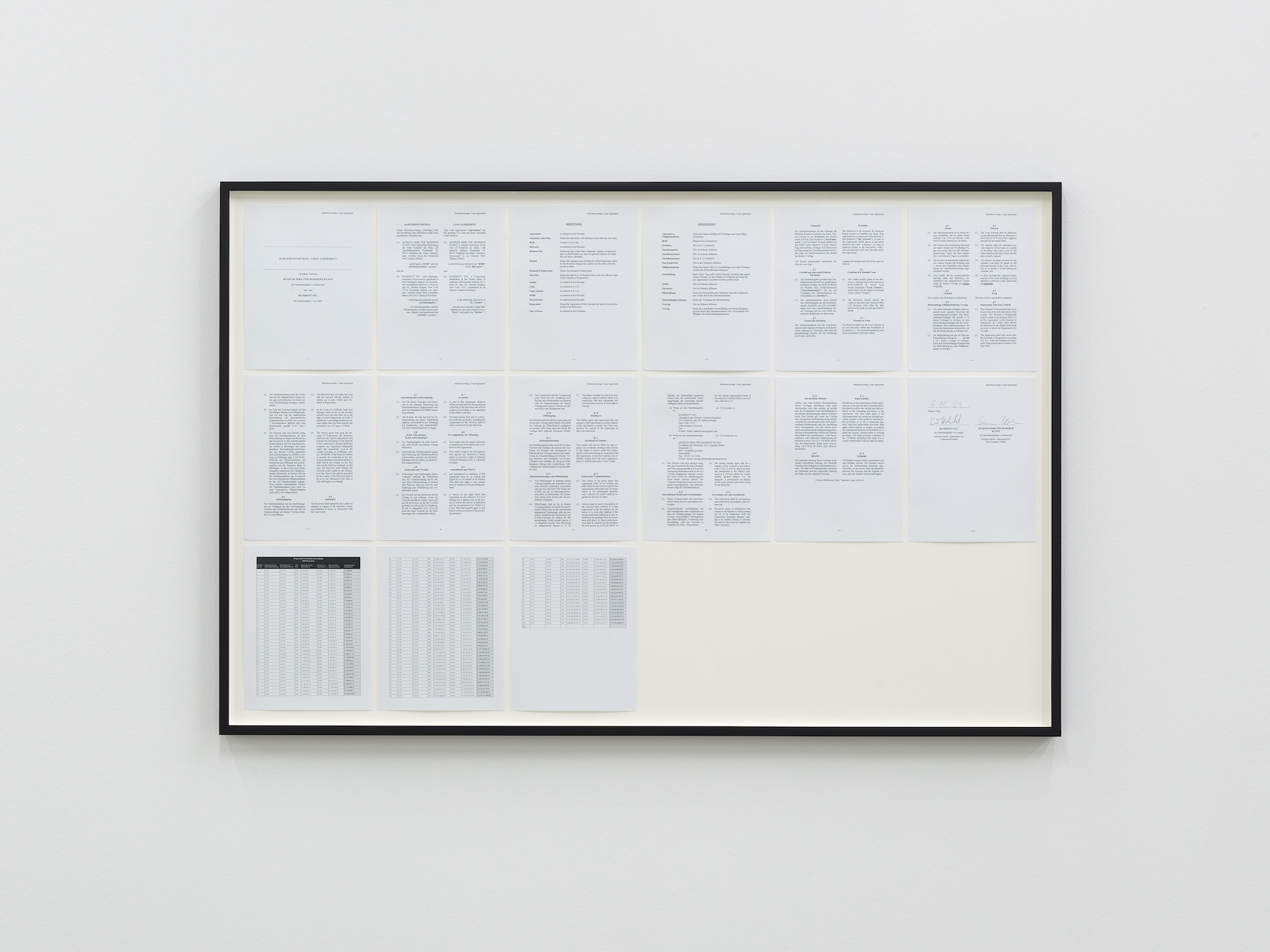

Cameron Rowland, Bankrott (Debt), 2022. Installation view, Amt 45 i, TowerMMK, Frankfurt am Main, February 11–October 15, 2023. Photo: Axel Schneider.

The epigraph of Rowland’s exhibition essay is taken from the book Slavery and Social Death (1982) by the sociologist and historian Orlando Patterson: “The slaveholder camouflaged his dependence, his parasitism, by various ideological strategies. Paradoxically, he defined the slave as dependent.” Here is a dialectic that has been uttered many times yet still bears repeating: the steady continuity of capitalism rests on the ever-accelerating destabilization of the many. Ostensibly smooth transactional infrastructures are built on the creation of imbalance and out-of-jointness. (Re)production and destruction are two sides of the same coin. Rowland gives artistic form to the dependency of present-day capitalism on slavery. By conscripting visitors into its spatial relations, their installations also tease out the psychological implications of the dependency alluded to in Patterson’s evocation of the great lengths an ostensible “master” will go through to mask the anxieties brought about by intersubjective double-binds.

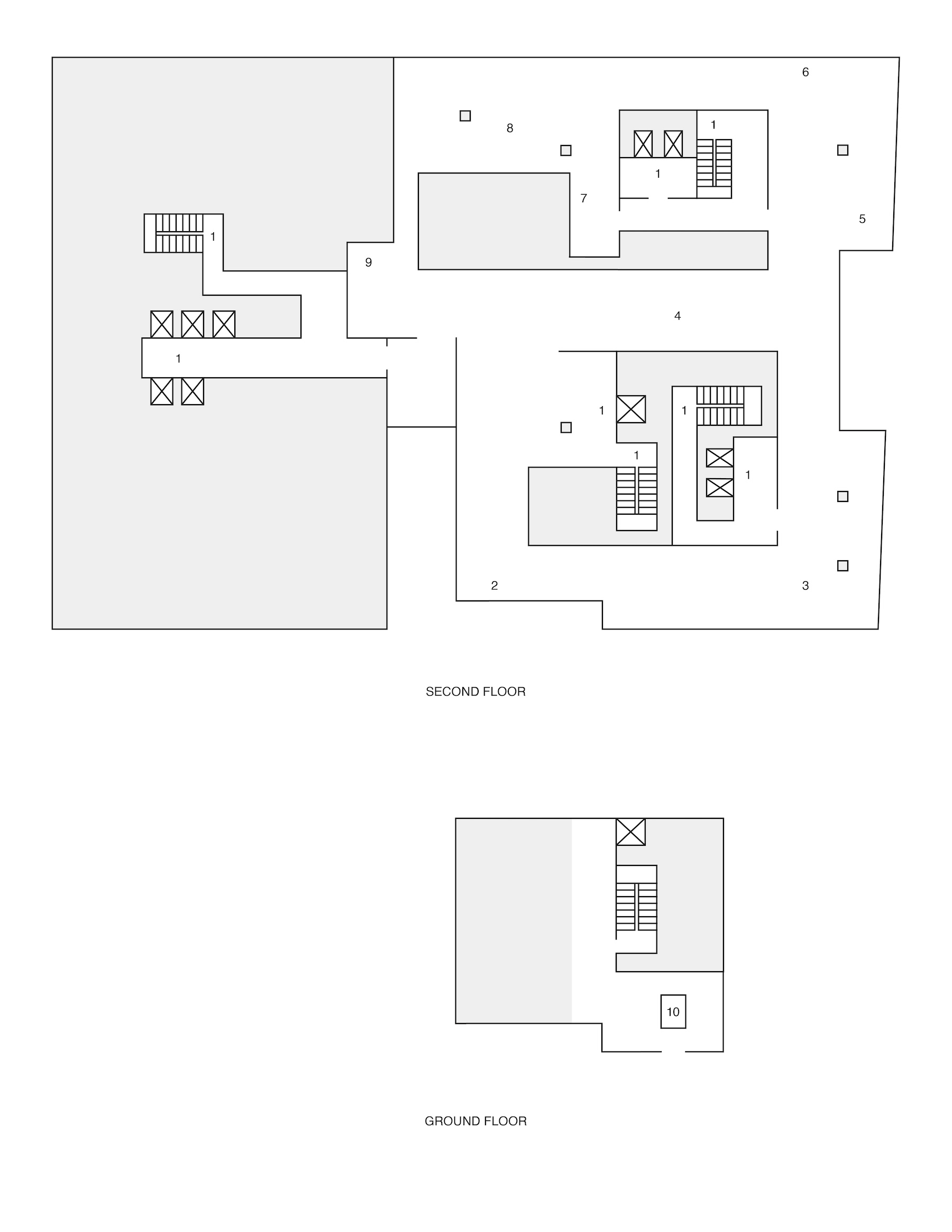

TowerMMK occupies an oddly shaped floor characterized by alternations of narrow corridors and wide rooms that foreshadow the space’s ultimate destiny as an office. Its current use as a gallery is a temporary concession made by Commerzbank and the real-estate corporation Tishman Speyer when the Tower was built in the early 2010s. In order to comply with the city’s demand that part of the structure be put to public use, the owners granted MMK a rent-free stint limited to fifteen years. Rowland points to this discomfiting agreement between high culture and late capitalism in the exhibition booklet: “TowerMMK materializes the relationship between Frankfurt’s public cultural development and private financial development. TowerMMK is subsidized through the rent paid by the numerous financial corporations located in the building. These include inheritors of the profits of slavery: Barclays, Schroders, J.P. Morgan, and Credit Suisse.” Public Use (2023), the name under which the entries and exits to the gallery space are listed as the first exhibit, makes sarcastic reference to this gift, given in expectation of invisible returns.

This relation between the location of the exhibition and Rowland’s art is compelling, but it also opens one of the pitfalls in writing about their work: an overemphasis on site-specificity. Site-specific art is often rooted in the desire to imbue a place with an experience of meaning that is available even to short-term visitors. Thanks to the museum, the city—formerly a fungible conglomerate of buildings, people, and incidents—begins to cohere into a story, even if it is largely one of greed, crime, and plunder. At first glance, Amt 45 i seems to fit this mold, an exhibition intent on teaching visitors about the history of Frankfurt so that they may leave the museum with a better understanding of the horrors behind the city’s façades, turning their experience of the city from one that is pre-determined by forces that render it exchangeable into a singular, didactic encounter. In this scenario, working through the sense of dislocation and anonymity of the city’s business district becomes a wellspring of redemption, as if reckoning with the occluded history of a place will remedy its alienating qualities.

Exhibition floor plan, Amt 45 i pamphlet, TowerMMK, Frankfurt am Main, February 11–October 15, 2023.

Amt 45 i latches onto Frankfurt’s status as a banking hub as well as the contractual relation between TowerMMK and its host, but the exhibition does not emerge from these conditions. In Rowland’s work, site-specific meaning remains a promise that is never truly delivered. A case in point is the repetition of formal strategies across their international solo exhibitions of the past decade. Each, including the current iteration, comprises a few framed documents, a matte steel plaque, something oblong, something heavy—lonely prosaic objects revalued as art by way of context. Each exhibition includes a pamphlet; all are designed with the same cool font and spare formatting, always accompanied by a floor plan. Considered as a series, these geometric constellations of rectangles, curves, and parallel lines evidence a relative indifference to their specific locations. The plans all look alike, a logical consequence of each venue partaking in the same transnational art-world circuit and the capital that flows alongside it, but also of the fact that the dispossession Rowland investigates is spectral rather than specific.

Whether a plan represents rooms in Frankfurt, London, or New York hardly matters. What does matter is the piercing of the floor plans’ spatial vacuums by numbers, which function as placeholders for the exhibited objects. In Frankfurt, the objects included a billhook, salt, pepper, two buckets, a loom, a sugar kettle, a postcard. Together with their counterparts at Rowland’s previous exhibitions, these things amount to a dispersed material history of the inseparability of culture and capital, capital and slavery, freedom and bondage, extraction and exchange—all suspended in a net whose nodes span from New York to London to Frankfurt and beyond. Rowland draws attention to place but refuses to alleviate the alienation of objects and visitors by returning them to site-specificity in order to “counter the sameness of places.”5

The pamphlet for Amt 45 i, as with Rowland’s previous exhibitions, features an essay that discloses the research that undergirds the exhibition. The artist thereby stakes a claim as their own best interpreter, exerting a large degree of control over the exegesis of the work. For the critic, this poses the risk of merely reiterating the information and arguments laid out by Rowland in the exhibition booklet or limiting oneself to a summary of the (admittedly crucial) economic interventions they stage. In Frankfurt, the latter comprised a contract between Bankrott Inc., founded by Rowland for the purpose of the exhibition, and MMK. In January 2023, Bankrott Inc. lent 20,000 Euros to the museum at the highest legal interest rate of 18%. A table spanning several framed pages predicts that MMK and its proprietor, the city of Frankfurt, will owe Bankrott more than 311 billion Euros in 2123, with the caveat that Rowland will never ask for the debt to be repaid. They concisely sum up the implications of this contract in the booklet: “As reparation, this debt is a restriction on the continued accumulation derived from slavery. As a negation of value, it does not seek to redistribute the wealth derived from slave life but seeks to burden its inheritors.” To which we may add, this “negation” is also a gain for inheritors, like the city of Frankfurt or Commerzbank, who reap cultural capital from Rowland’s intervention into their orbit. The term negativity might be used to describe the stakes of Rowland’s work, as the artist wrestles with the perpetual desire for and simultaneous impossibility of negation rather than performing its achievement in the realm of art through gestures of countering.

Faced with such conceptual somersaults, one critical choice would—and frequently has been—to push the aesthetics of Rowland’s work to the sidelines. But form haunts even the most mind-over-matter approaches to art, and engaging with aesthetic experience (and its impossibility) plunges us right into the most complicated implications of Rowland’s artistic choices.

Amt 45 i, installation view, TowerMMK, Frankfurt am Main, February 11–October 15, 2023. Photo: Axel Schneider.

Amt 45 i accessed the fraught balancing acts of extractive capital through the positioning of objects in space. At TowerMMK, only rarely did I find myself in a spot where more than one object was visible. The memory of other things spun threads of connection between the dispersed objects. An eighteenth-century loom from Osnabrück, Germany, an object of considerable size and authority, became related to a pair of plastic buckets filled with oxalic acid located across the gallery space. The loom was likely used to weave coarse linen fabrics that were sold across the Atlantic as slave garb and became known as Osnaburgs. Oxalic acid is a common household stain remover that offered a means for sabotage, like raw manioc or ground glass, when used as a poison against slaveholders, overseers, or livestock. Looking down at the twin pails, I felt a pull from their weighty counterpart, as if the entire floor was tilting toward the heavy wooden loom, spinning yarn for surplus value, until the buckets slide, tumble, roll away, tearing apart a perfect pair. In the context of Amt 45 i, this relation between balance and out-of-jointness maps onto debt’s relation to profit and is therefore economic and political in scope.

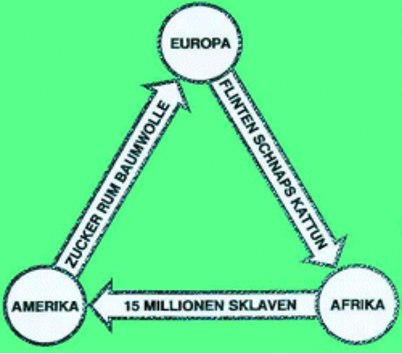

Balanced reciprocity is the ideological screen that obscures extraction, and like most ideologies, it circulates through images. I have a memory of being taught about the slave trade in history class at a secondary school in Germany, circa 2011. The teacher handed out a diagram: three arrows connect Europe, West Africa, America. Text inside the arrows read: “Guns, alcohol, textiles—15 million slaves—sugar, rum, cotton.” One exchanged for the other, which implied guns equal humans equal sugar.

Erwin Raeth, Dreieckshandel (triangular trade), date unknown. © Erwin Raeth, courtesy Gesellschaft für Schleswig-Holsteinische Geschichte.

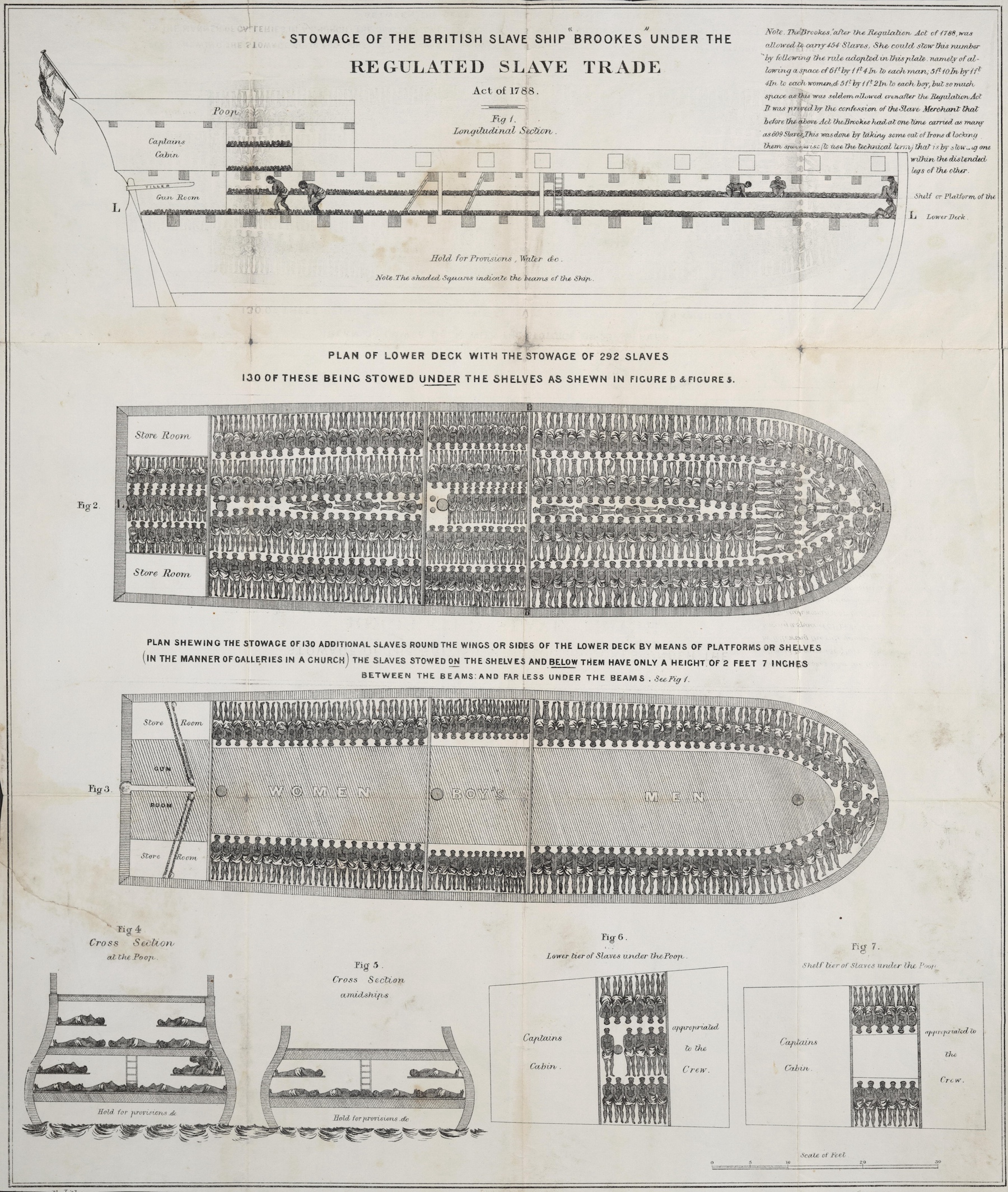

This cruelly abstract image was presented as a visualization of global exchange rather than the schematic rendering of a crime without a single agent. Its equilibrium is based on a willful omission of images like the stowage of the Brookes, a British slave ship, filled to the rim with bodies, their weight and size quantified to prevent the vessel from sinking. This arrangement is another balancing act, not in the interest of survival but of continued exchange, which is really extraction.

Stowage of the British Slave Ship Brookes under the Regulated Slave Trade Act of 1788, 1790. Etching, 48 x 40 cm. Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Washington, DC, public domain.

Amt 45 i confronted visitors with a phenomenological experience of destabilization dressed in measured restraint. Compare this to minimalist art—an ineludible reference for Rowland’s work—which also favors the sparse display of objects in otherwise empty spaces. The question that comes up in this comparison is again one of fraught dependency: Does it relegate Rowland to a genealogy of predecessors who considered relations between bodies and objects but omitted the fraught racialized relations inside and outside the gallery? My choice to compare creates an uneasy dependency between Rowland and a whitewashed version of the twentieth century. That’s the trap of the master narrative. But the dependency also works the other way around, in a retroactive reading of Modernism and modernity vis à vis Rowland’s positioning of racial capitalism at their core.

Here is a brief gloss of canonical art history: Minimalism played a trick on the Modernist obsession with disinterested aesthetics and autonomy by embedding objects into worldly contexts, thereby turning the relation between object, beholder, and the space shared by both into the medium of art itself. At least initially, the perfect stacks and mirrored cubes of Minimalism quarreled with the transcendental status of high art. This quarreling is essential for Rowland’s practice too: the exhibits in Frankfurt—bucket, loom, billhook—are encountered as objects of the world at hand. However, that does not mean that they are reduced to fungible entities, meant for passive consumption. Instead, they may be seen as tools that, like the poisonous content of the buckets, can be worked to dismantle the material conditions of subjection, even if that dismantling is never fully achieved.

Cameron Rowland, Mackandal (Oxalic Acid), 2022. Installation view, Amt 45 I, TowerMMK, Frankfurt am Main, February 11–October 15, 2023. Photo: Axel Schneider.

Thickening the threads between art, economy, and subjectivity, Rowland’s work suggests that all three rest on the occlusion of dependencies, which allows them to posture as sites of autonomy. Qua Orlando Patterson, the would-be transcendental subject is revealed to be a parasite, frightfully camouflaging their dependence on the enslaved. Qua Rowland’s aesthetic strategies, the possibility of aesthetic experience itself is put into question: each art object may also be regarded as a tool that is contingent on its user and intervenes in the material conditions from which it emerges.

A thick rope, slightly above knee-level (Bug trap, 2023) crosses a corridor dividing Amt 45 i in half. This could be another image of balance: a body, staggering with graceful precarity from one side to the other. But this rope is also a trap that pulls toward the ground, named after the so-called bug traps that fugitive slaves in North America would set up to halt the horses of mounted patrols in their pursuit.

If Amt 45 i was meant to be experienced phenomenologically, through its relations, the question remains: By whom and how? Am I the bug that will stumble? Minimalist art relegated the specific body of the beholder to the sidelines in favor of a presumed general experience of gestalt. The rope, according to this logic, would be an object in space that everyone relates to similarly. In Rowland’s case, however, the rope is not merely the facilitator of phenomenological and aesthetic experience but also a trap—and the joke is on the critic whose quest for an “art experience” in Frankfurt turns into a stumble, unraveling as it happens.

Luise Mörke is a writer and critic based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Berlin.