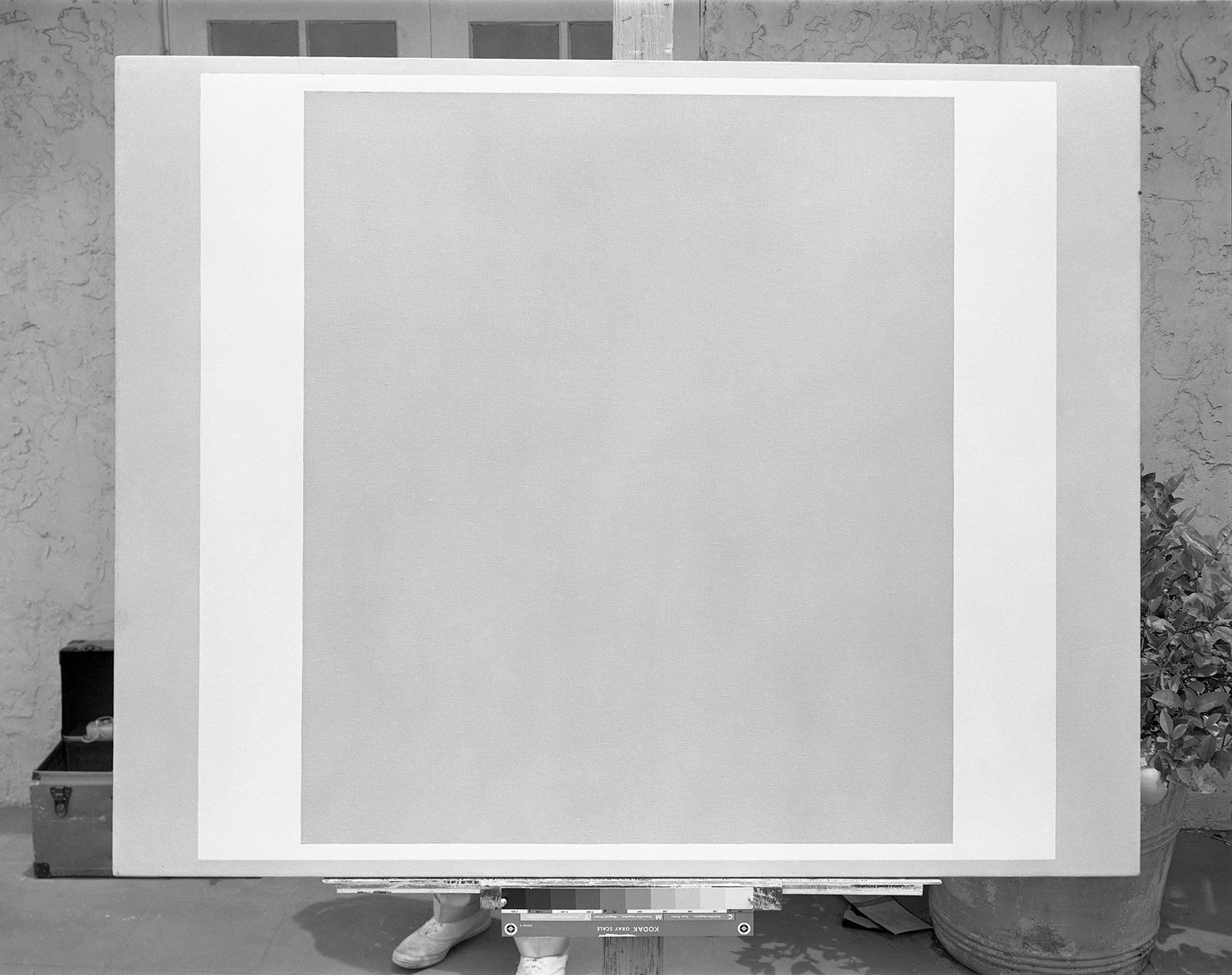

In early 2016, artist Fiona Connor visited the archive of photographer Frank J. Thomas in Portland, Oregon. From the 1950s to the 1970s, Thomas was the go-to photographer of the Los Angeles art world, regularly hired by artists, dealers, collectors, galleries, museums, and publishers to photograph art-works, exhibitions, and events related to the lively art scene growing in and around the city.1 While seeking documentary photographs of site-specific works by Los Angeles artists such as Maria Nordman, Michael Asher, and Robert Irwin, Connor encountered Thomas’s photographs of paintings by John McLaughlin. This was Connor’s first introduction to McLaughlin’s work. Thomas was hired to document a series of McLaughlin’s works in preparation for the painter’s first East Coast retrospective, organized by James Harithas and held at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., in 1968.2 The black-and-white photographs, taken with a large format camera, show each austerely abstract painting propped on an easel placed among everyday objects in various locations around McLaughlin’s home, in Laguna Beach, California. There is an ironic disjuncture between the artist’s intended program and what the documentary photographs picture: Whereas McLaughlin used a vocabulary of “neutral forms” in his paintings to “free the viewer from the demands or special qualities imposed by the particular,” in these photographs, we see only particularities within the frame.3 This vivid contrast between McLaughlin’s abstract paintings and their lived-in setting captured Connor’s interest.

In Thomas’s photographs, it is impossible to view McLaughlin’s paintings apart from the manifold details that surround them. Multiple potted plants and cuffed khaki pant legs and white tennis shoes (presumably belonging to the artist) appear in some of the photos, all suggestive of a comfortable, middle-class lifestyle. In other images, the house’s window shutters and panes echo the rectangular forms found within the paintings themselves. Although the mundane details that surround each of the paintings in the photographs were incidental, meant to be cropped out when reproduced in catalogs or other printed matter, these documentary photos nevertheless reframe our perception of McLaughlin’s paintings, counteracting the artist’s claim to “total” abstraction by making palpable the paintings’ relation to their maker in a particular time and place.4 Connor was struck by how the paintings in the photographs seemed to act as “reverse frames,” directing her eyes to their margins and bringing into view their surrounding context.5 Her initial search for documentation of site-specific works uncovered another type of specificity, one in which the documentation of a work, or the mediation of a work through documentation, itself embodies the concept of specificity, by binding an object to a situational moment in time from a particular point of view.

Frank J. Thomas, Documentation of “No. 17, 1965” by John McLaughlin, Laguna Beach, n.d.. Courtesy of Frank J. Thomas Archives.

Connor’s mediated encounter with McLaughlin’s work in Thomas’s archive led to an ongoing project. In the artist’s words, the project is “roughly about the way art is documented and how it lives past its primary physical form.”6 Since encountering the photographs, Connor has researched and analyzed a range of materials related to McLaughlin’s work, from photo documentation and old magazine articles to condition reports of existing paintings. She has examined papers saved in the artist’s archive and traveled to Orange County to see the houses (still extant) in which the artist lived and painted.7 Connor has responded to her findings by producing uncannily precise replicas of found objects—such as newspaper reviews on McLaughlin and window frames from the artist’s longtime home—and exhibiting them alongside works by other artists and photographers. She has given public talks, updated for each occasion, that reflect the current state of her evolving thinking and research.8

In these pages, Catherine Wagley wrote about “the young female artist as historian,” a young woman artist, often in her twenties or thirties, who comes across and is inspired by the work of a forgotten or lesser-known older woman artist.9 The older artist’s “unruly” work resists integration into dominant art historical narratives; the goal of the younger artist is to figure out how to write a non-revisionist history that remains faithful to the spirit of her work. Wagley argues: “The younger woman’s task becomes preserving that complexity, and narrating the artist’s life in a way that allows her to remain outside of the limiting frame of canonical narratives. It also becomes acknowledging a personal stake while giving her subject space and autonomy.”10

Like Wagley’s “young female artist,” Connor’s approach to history is not revisionist, in that her object is not to replace one dominant narrative of the art historical canon with another. Rather, Connor’s approach to history is to de-center her subject by bringing into view the discourse that surrounds it: John McLaughlin as the discursive production of “John McLaughlin.” Whereas the task for Wagley’s “young female artist” is ultimately one of recovery (a model of history writing that will, when most effective, instigate a “fundamental reorganization of the institutions that govern us”11), the task for Connor is one of deconstruction. And while the writing on woman artists such as Marjorie Cameron, Eve Babitz, and Barbara T. Smith is now gaining momentum,12 McLaughlin was recognized by the art world during his lifetime—for example, his work appeared on the January 1964 cover of Artforum—before sliding into obscurity after his passing in 1976.13 Interest in McLaughlin’s work has grown since the Getty-sponsored initiative Pacific Standard Time in 2011 and 2012, and it received another boost recently with a retrospective at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), which closed in April 2017. Yet one could argue that his work has not quite entered the mainstream. For example, it is significant that Connor, who received her MFA from California Institute of the Arts, did not know of McLaughlin’s paintings before seeing the photos of them in Thomas’s archive.

Connor’s project has produced work that is significantly historical, but what kind of historical work is this? Clearly, Connor is not a historian in a strict sense, but she diverges even further from that tradition by not constructing historical narratives, at least not in the forms that the project has taken to date. Instead of writing history by abstracting an object from its context into language and using narrative strategies, such as cause-and-effect, Connor has set up an arena that allows objects to speak for themselves, while keeping them tethered to their specificity and historicity as much as possible. In December 2016, Connor curated a group exhibition titled Ma, at Chateau Shatto, in Los Angeles. In this most recent installation of her larger project around McLaughlin, Connor placed Thomas’s photos of McLaughlin’s paintings, a painting by McLaughlin, and her own work on McLaughlin into conversation with historical and contemporary works by other artists and photographers. What model of history is this, and how does a viewer experience such a paradigm? What might be at stake in this historical model?

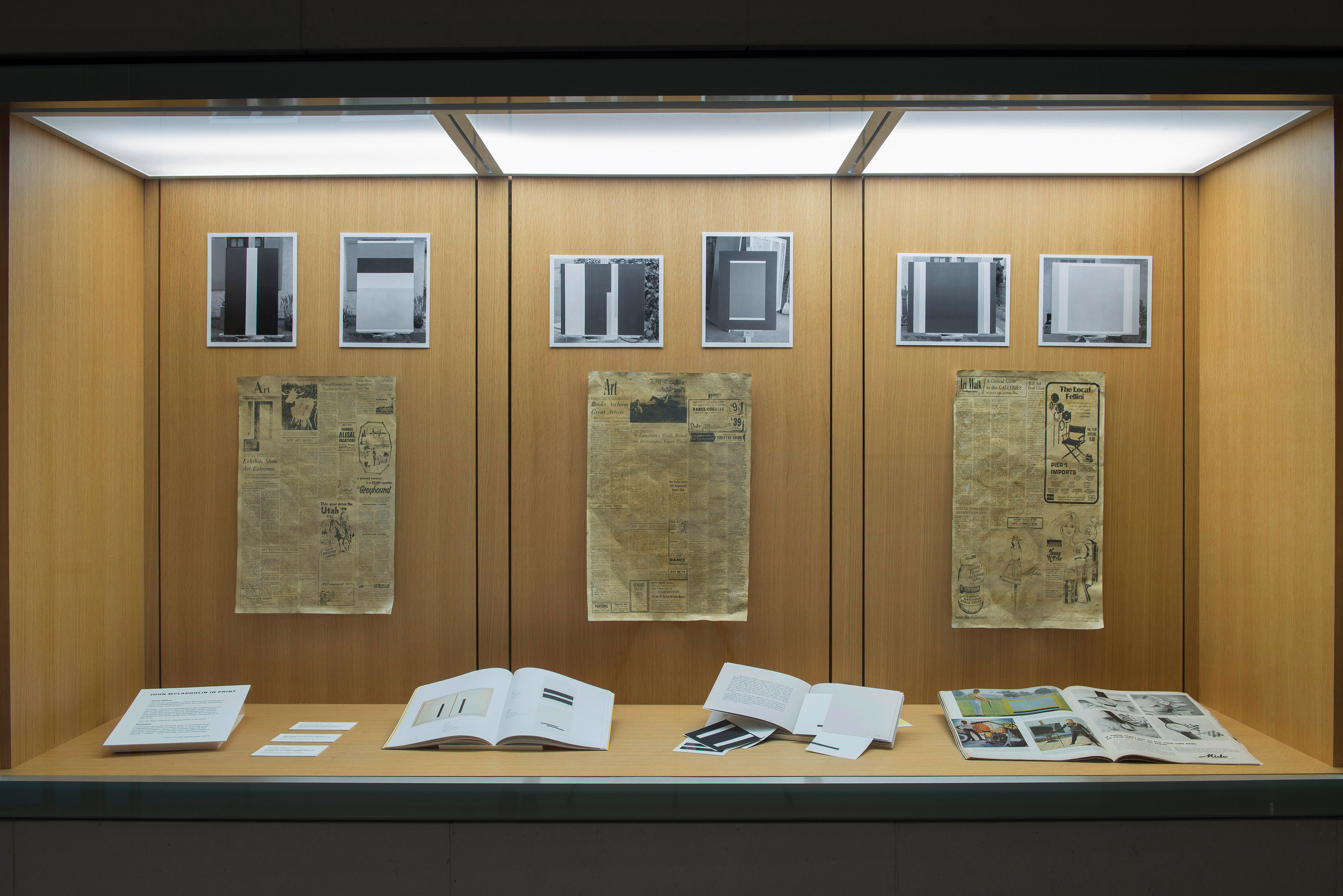

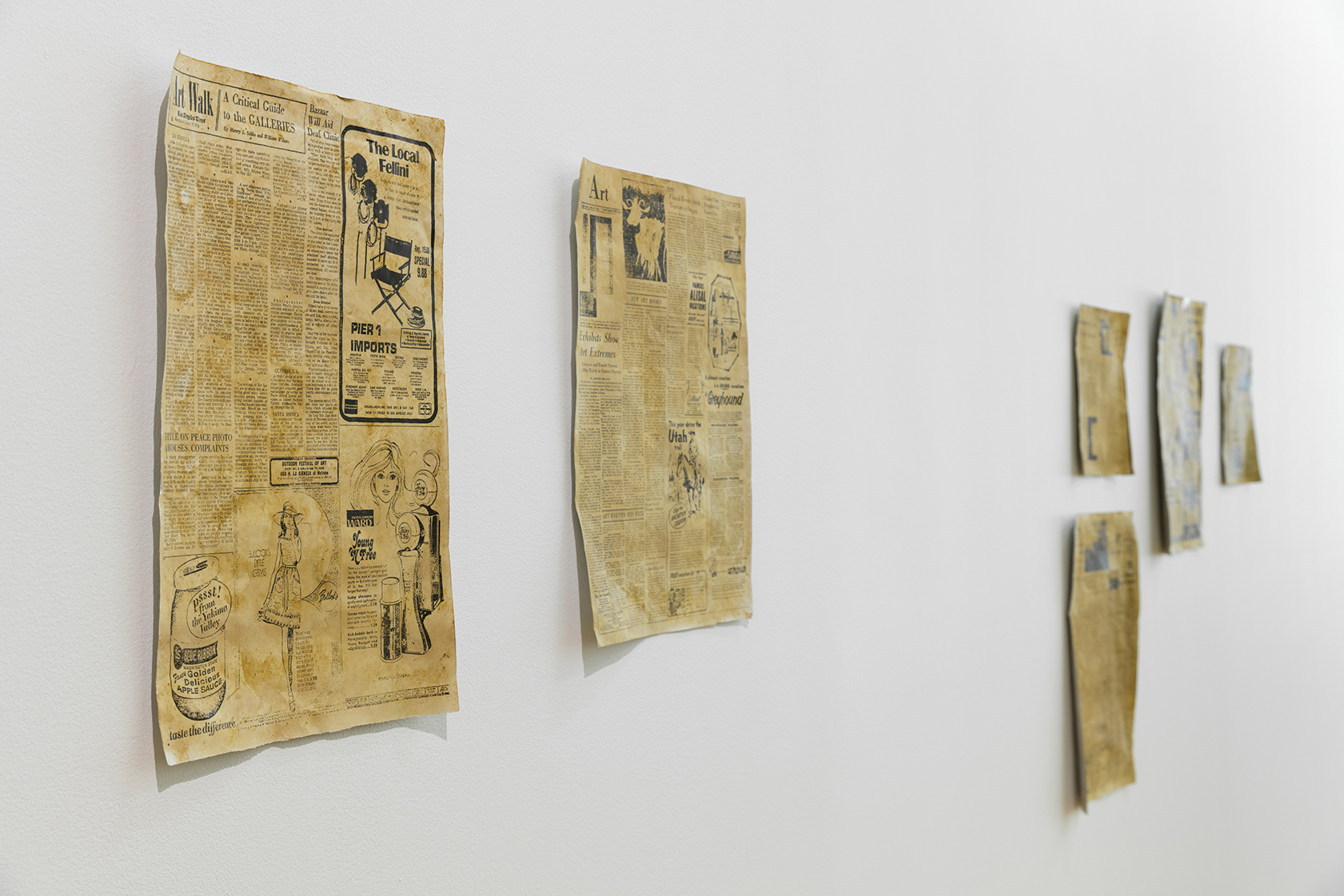

Before Ma opened, Connor presented three related works.14 The first two were a presentation of objects and a public lecture that took place in New Zealand. In the fall of 2016, Connor installed a mini-exhibition, titled John McLaughlin in Print (2016), in a display case at the Auckland Art Gallery. Six of Thomas’s photographs of McLaughlin’s paintings were displayed in a row. Below these photos were three works by Connor—full-scale reproductions of reviews on McLaughlin published in the Los Angeles Times during the artist’s lifetime. The reviews were scanned from archived microfiche that Connor found at the Los Angeles Public Library. She silkscreened facsimiles of the newspaper pages onto aluminum foil that was coated and tinted to appear yellowed and worn with age. At the bottom of the case were two exhibition catalogs on McLaughlin, an article featuring McLaughlin in Life magazine, and a didactic text that included the title of Connor’s installation, a statement about her project, and her name and the work’s date (“September 2016”). On September 20, 2016, Connor gave a lecture on her project at the Elam School of Fine Arts at the University of Auckland.

Fiona Connor, John McLaughlin in Print, 2016. Installation view, Research Library display case, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, September 19–Oct 19, 2016. Courtesy of E H McCormick Research Library, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

The third work in Connor’s project was a group exhibition that she curated at Minerva gallery in Sydney, Australia, from October 29 to December 10, 2016. This group exhibition, titled Fiona Connor, Sydney de Jong, Audrey Wollen, featured one work by each of the artists in the show’s title.15 In one room of the gallery, a projector played Wollen’s Objects or Themselves (2015), a video that interweaves narratives about the suffragette Mary Richardson’s slashing of Velazquez’s Rokeby Venus (1647–51) and the experience of procedures that Wollen underwent for cancer treatment as a teenager. For All the Doors in the Walls (2016), Connor had all of the gallery’s doors removed from their hinges and embedded into the walls of the gallery for the course of the exhibition. De Jong’s contribution was Colored Clay Pieces (2016), a set of multi-colored ceramic cups and plates meant to be used by the gallery staff, not for display purposes only. As a supplement to the works in the exhibition, Connor commissioned five people to write five different press releases for the show and sent them a selection of Thomas’s photos of McLaughlin’s paintings. It was up to the writers to decide whether or not to address Thomas’s photos in their texts. Only one writer—Harry Dodge—did.16

The exhibition Ma included Wollen’s video Objects or Themselves and de Jong’s Colored Clay Pieces, as well as works by Judy Fiskin, John McLaughlin, Frank J. Thomas, Bedros Yeretzian, and Connor. To produce a visual frame for the show, Connor worked with Sebastian Clough on its exhibition design.17 The contributors to the exhibition were heterogeneous and diverse, representing different generations, professions, and sexes. All have participated in the Los Angeles art world, past and present.

Fredrik Nilsen, Documentation of Ma at Chateau Shatto with works by Fiona Connor, Judy Fiskin, Sydney de Jong, John McLaughlin, Frank J. Thomas, Audrey Wollen and Bedros Yeretzian, 2016–17. Digital image. Courtesy of Fiona Connor and Fredrik Nilsen.

The exhibition’s point of departure was the Japanese concept of ma—the interval between two or more things. Ma can refer to physical space, such as a room or an opening between two walls, or a temporal one, such as a rest or pause between notes in music. Ma implies an inherently relational dynamic—something perceived as between things—and conveys both objective and subjective meanings: it can signify a gap existing in space and/or time as well as one’s perceptual recognition of this gap.18 This multivalent concept was of crucial importance to McLaughlin, who was interested in the use of “empty” or negative space in traditional Japanese artworks; he cited the influence of fifteenth-century painter Sesshū Tōyō and his concept of the “Marvelous Void” in particular. McLaughlin wrote: “Certain Japanese painters of centuries ago found the means to overcome the demands imposed by the object by use of large areas of empty space. This space was described by Sesshu as the ‘Marvelous Void.’ Thus the viewer was induced to ‘enter’ the painting unconscious of the dominance of the object. Consequently there was no compulsion to ponder the significance as such. On the contrary, the condition of ‘Man versus Nature’ was reversed to that of man at one with nature and enabled the viewer to seek his own identity free from the suffocating finality of the conclusive statement.”19 In his paintings, McLaughlin sought to provide the viewer with spaces for contemplation. His paintings are not meant to be deciphered and interpreted, but rather experienced.

Extending the concept of ma into a spatiotemporal realm, Connor set up in her exhibition a constellation of objects that did not illustrate a curatorial thesis per se but rather offered the viewer a space in which to consider how objects, images, and ideas are mediated through modes of representation and how one’s reading of them is dependent upon their context. The impossibility of perceiving an exhibited work apart from its surrounding context is the defining characteristic of the exhibition Ma.

A stack of press releases printed on marbled pink paper on a ledge greeted visitors as they entered the gallery. Resting on top of the pile was a crystal paperweight with beveled edges, about the size of a large bar of soap. When I picked it up to grab a sheet of paper, I could see that the exhibition’s title, dates, and the gallery’s name were etched onto its surface, and a decorative border traced its inner edge. A glance at the floor plan-cum-checklist printed on the reverse side of the press release revealed that this object was Mutual Enemy Arousal Souvenir: ‘Ma’ Chateau Shatto, 12/10/16–01/14/17, 2016 (2016), by Bedros Yeretzian.

Fredrik Nilsen, Documentation of Ma at Chateau Shatto with works by Fiona Connor, Judy Fiskin, Sydney de Jong, John McLaughlin, Frank J. Thomas, Audrey Wollen and Bedros Yeretzian, 2016–17. Digital image. Courtesy of Fiona Connor and Fredrik Nilsen.

Two floating shelves painted white and lined with beige linen cloth were built into the left wall. Each shelf held five eight-by-ten-inch black-and-white photographs from Thomas’s series that documents paintings by McLaughlin, taken at the painter’s home in Laguna Beach and in other locations in the 1960s and 1970s. The light-colored lines in some of McLaughlin’s paintings were echoed by the white borders framing each photograph, which in turn mirrored the white framing the beige shelf surfaces, which emulated the white ceiling and wide white border along the top of the gallery’s walls, which were painted beige below. The photographs were not protected by a cover, so one could bend down and look very closely at the prints.

Fredrik Nilsen, Documentation of Ma at Chateau Shatto with works by Fiona Connor, Judy Fiskin, Sydney de Jong, John McLaughlin, Frank J. Thomas, Audrey Wollen and Bedros Yeretzian, 2016–17. Digital image. Courtesy of Fiona Connor and Fredrik Nilsen.

Six works by Connor hung on the opposite wall of the gallery: Ma #4–9 (Newspaper article featuring John McLaughlin from the Los Angeles Times) 1956–87 (2016). Each work consisted of tinted aluminum foil on which a review of McLaughlin from the Los Angeles Times was silkscreened (three of these had been included in the display case at the Auckland Art Gallery the previous fall). The thin pieces of foil were taped directly onto the wall and their edges curled inward, which allowed me to see the untinted silver surface of their backs. I had to stand rather close to the works in order to read them, and even then not all of the text was legible. Most discernible were the articles’ titles and sometimes their authors’ bylines, such as “John McLaughlin’s Search for the Infinite by Henry Seldis,” “McLaughlin’s Works Encourage Meditation by Constance Perkins,” or “McLaughlin’s Work, Based on Rectangles, Gives Thrill.” Often degraded reproductions of McLaughlin’s paintings and numerous advertisements accompanied the texts. Like Thomas’s photographs across the way, these exposed surfaces conveyed a sense of fragility despite being made of durable material.

Fredrik Nilsen, Documentation of Ma at Chateau Shatto with works by Fiona Connor, Judy Fiskin, Sydney de Jong, John McLaughlin, Frank J. Thomas, Audrey Wollen and Bedros Yeretzian, 2016–17. Digital image. Courtesy of Fiona Connor and Fredrik Nilsen.

A freestanding wall occupied the center of the main gallery space. On one side, closer to the gallery’s entrance, I could see Wollen’s video Objects or Themselves playing on a loop. As I sat down on a bench-like structure extending from the wall to view this work, I realized I had been hearing her video since I walked into the gallery, but not listening to it. In the video, textual fragments of the voiceover periodically appear over an image of Velazquez’s Rokeby Venus, allowing a word or phrase to linger. I learned about the phenomenon of the “Venus effect,” in which a painted figure gazing into a mirror, such as the one in Rokeby Venus, is assumed by viewers to be gazing at herself, although the figure is actually looking out at you, the viewer. I heard about the British suffragettes in the early twentieth century, Richardson’s decision to slash the Rokeby Venus as a feminist statement, and the “successful” repair of the painting that followed. Weaving in and out of this historical narrative was a personal account of Wollen finding a lump on the side of her chest and the difficult and drawn out process of being diagnosed, treated, and finally having the tumor removed. The poignancy of the artist’s emotionally and intellectually charged tale left me feeling momentarily stunned.

On the opposite side of the freestanding wall was McLaughlin’s painting #13 (1964). Symmetrically composed, with one half painted black with a white vertical line and the other half painted white with a black vertical line, the painting shared the center point of the exhibition with Wollen’s Objects or Themselves. On the one hand, the two works could not be more opposed: McLaughlin’s abstract formal program of colorless rectangles and lines versus Wollen’s audio and visual time-based meditation on gender, violence, and the politics of looking. On the other hand, as I stood in front of McLaughlin’s painting, residual emotions and thoughts from my experience of Wollen’s video (which was starting to play again) colored my perception of it. I couldn’t help but see McLaughlin’s painting as a kind of body, its aging skin-like canvas marked by fine cracks and scratches accumulated over time.

Fredrik Nilsen, Documentation of Ma at Chateau Shatto with works by Fiona Connor, Judy Fiskin, Sydney de Jong, John McLaughlin, Frank J. Thomas, Audrey Wollen and Bedros Yeretzian, 2016–17. Digital image. Courtesy of Fiona Connor and Fredrik Nilsen.

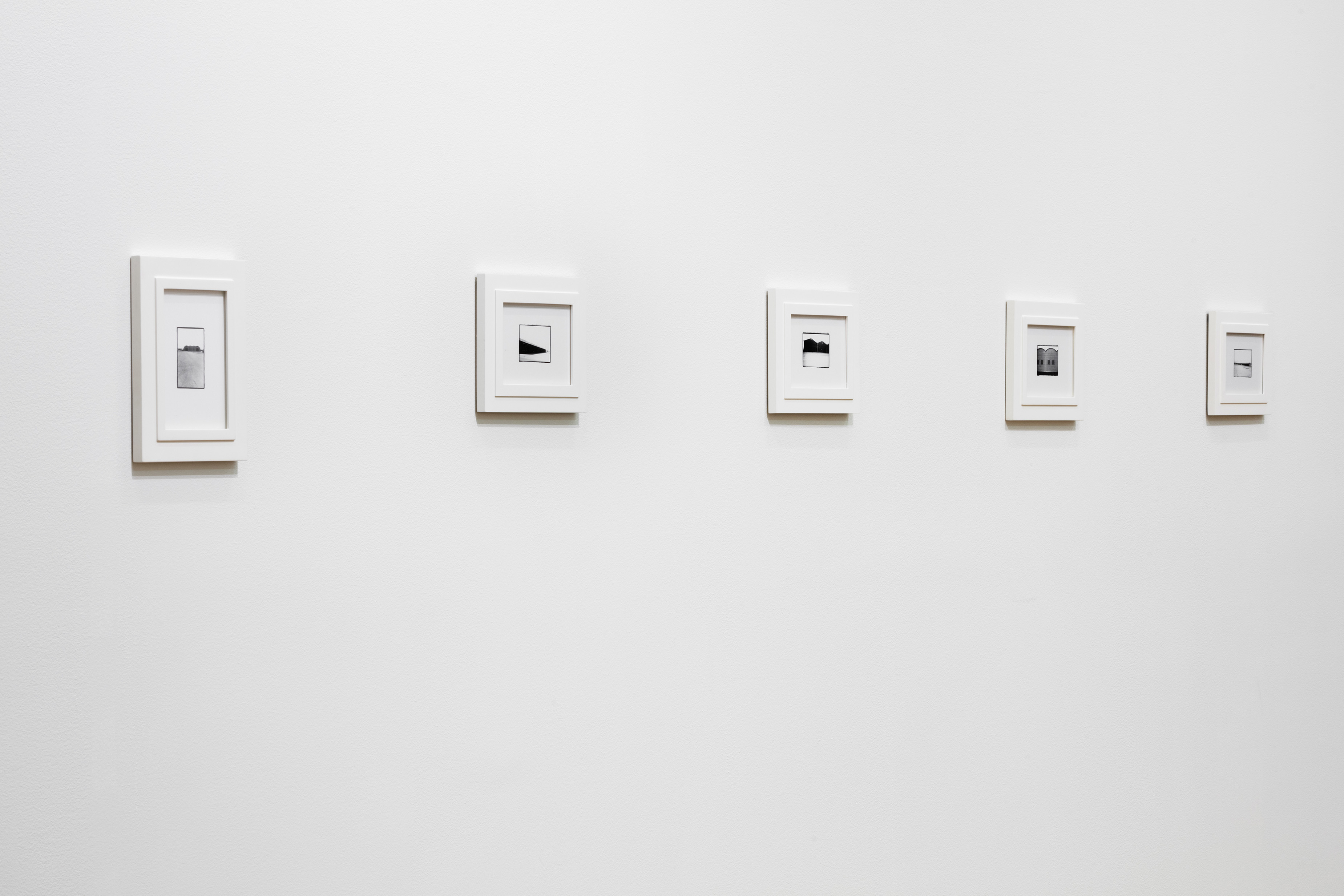

A series of five photos from Judy Fiskin’s Military Architecture series (1975) and Connor’s sculptural installations Ma #1 and Ma #2 (2016) were installed in the back of the gallery. In Fiskin’s diminutive black-and-white photographs, buildings in the shape of repeated or elongated geometric forms stood silhouetted against bright skies.20 Connor’s Ma #1 and Ma #2 replicated two adjacent bedroom windows in McLaughlin’s former home in Dana Point. The rectangular window frames and the geometric division of their panes recalled the compositions of McLaughlin’s paintings. The glass panes and window frames were installed directly into the gallery’s walls, revealing found compositions of more rectangles created by the vertical wooden studs and horizontal supports within the wall. Exposing a portion of the gallery’s inner skeletal structure, Connor’s sculptures underlined the perceptual and conceptual inseparability of a work from its context. Making literal the timeworn metaphor of “painting as a window,” the two works also asked the viewer to examine McLaughlin’s windows as intently as one might examine his paintings. In proximity to McLaughlin’s #13, Fiskin’s and Connor’s works drew the abstract painting into the language of architecture. The trio of works spoke to the ubiquity of rectangles in modern art and modern industrial construction—for military and non-military use alike—thus drawing connections between abstract forms, mass production, and the built environment.

Fredrik Nilsen, Documentation of Ma at Chateau Shatto with works by Fiona Connor, Judy Fiskin, Sydney de Jong, John McLaughlin, Frank J. Thomas, Audrey Wollen and Bedros Yeretzian, 2016–17. Digital image. Courtesy of Fiona Connor and Fredrik Nilsen.

Finally, in the gallery’s back room was de Jong’s Colored Clay Pieces (2016), a set of nerikomi cups, plates, and a large bowl, which the artist invited the gallery staff to use during the run of the show. The nerikomi technique involves creating bold patterns by taking different colored clays and pounding them together into a mold or throwing them on a wheel.21 A combinatory method was also apparent in Ma #3 (Inspiration Board of Sydney de Jong) (2016). In this work, Connor utilized her silkscreen-on-coated-foil technique to faithfully reproduce arrangements of photographs pinned on a cork board in de Jong’s studio.22

In his 1971 essay “From Work to Text,” Roland Barthes proposed a model of a “text” that offers a key to navigating Ma and Connor’s project more generally.23 Barthes differentiates between what he calls a “work” and a “text”: whereas a work takes the form of an object, a text takes the form of activity. A work can be “held in the hand,” whereas a text is “held in language.”24 A text is intrinsically intertextual and depends on what Barthes calls the “stereographic plurality of its weave of signifiers.”25 He evocatively likens the act of reading a text to passing through a foreign landscape already richly inhabited:

The reader of the Text may be compared to someone at loose ends (someone slackened off from the “imaginary”); this passably empty subject strolls (it is what happened to the author of these lines, then it was that he had a vivid idea of the Text) on the side of a valley, an oued flowing down below (“oued” is there to attest to a certain feeling of unfamiliarity); what he perceives is multiple, irreducible, coming from a disconnected, heterogeneous variety of substances and perspectives: lights, colors, vegetation, heat, air, slender explosions of noises, scant cries of birds, children’s voices from the other side of the valley, passages, gestures, clothes of inhabitants near or far away. All these incidents are half-identifiable: they come from codes which are known but their combination is unique, founding the stroll in a difference repeatable only as difference. So the Text: it can be itself only in its difference (which does not mean its individuality), its reading is semelfactive (this rendering illusory any inductive-deductive science of texts—no “grammar” of the text), and nevertheless woven entirely with citations, references, echoes: cultural languages (what language is not?), antecedent or contemporary, which traverse it through and through in a vast stereophony.26

Fredrik Nilsen, Documentation of Ma at Chateau Shatto with works by Fiona Connor, Judy Fiskin, Sydney de Jong, John McLaughlin, Frank J. Thomas, Audrey Wollen and Bedros Yeretzian, 2016–17. Digital image. Courtesy of Fiona Connor and Fredrik Nilsen.

This description of reading a text as a semelfactive experience woven with “citations, references, echoes” recalls my own sensory experience of Ma as a “stroll” through a multidimensional space composed of formal and textual references that comprised the exhibition’s installation. The exhibited works in Ma were presented in a strikingly non-hierarchical manner—traditionally fine art mediums next to traditionally commercial mediums, non-functional objects next to functional objects, originals next to copies, and copies presented as originals.

Another important feature of a “text” is how it fuses together space and time: a text exists in motion. Barthes places particular emphasis on this aspect: “[T]he Text is experienced only in an activity of production. It follows that the Text cannot stop (for example, on the library shelf); its constitutive movement is that of cutting across (in particular, it can cut across the work, several works).”27

This lateral movement of “cutting across” is most apparent in the final work included in Ma. Connor commissioned photographer Fredrik Nilsen to document his experience of the exhibition as a contribution to it.28 Nilsen’s position as a photographer of artworks and exhibitions in Los Angeles is comparable to Thomas’s from the 1950s to 1970s. These photographs were not physically displayed at Chateau Shatto and are publicly presented here in X-TRA for the first time. Connor’s inclusion of this last work raises a series of questions: How should we understand the material, temporal, and conceptual form of this exhibition? Does it continue to be “on view” in some sense, for example, in this very instance as you read this text and see Nilsen’s images? The inclusion of his photographs in Ma draws attention to and blurs the boundaries between the exhibition and its discursive reception. In this way, Connor’s project opens up a new, dilated historical perspective, one that frames the “work” as a text, something that is ongoing and forward looking, set to expand through future sites of reception. But what or where are the boundaries of this text that Connor has put into play?

The recent retrospective John McLaughlin Paintings: Total Abstraction, held from November 13, 2016, to April 16, 2017, at LACMA, offers an instructive contrast to Ma. That Connor’s exhibition ran concurrently with LACMA’s was, according to the artist, purely coincidental. The LACMA exhibition, co-curated by Stephanie Barron and Lauren Bergman, included about fifty paintings by McLaughlin as well as a selection of his drawings and paper collages. The works were arranged chronologically and demonstrated his stylistic development over the years—from his early paintings with colorful biomorphic compositions to his final paintings with black and white rectangular forms. A variety of supplemental materials—from video interviews playing on a monitor to a homage titled “Appreciation” by Edward Albee and quotations by McLaughlin printed on the exhibition’s walls—all served to reinforce a notion of the artist as the single—and by implication, final— author of his work.

Fredrik Nilsen, Documentation of Ma at Chateau Shatto with works by Fiona Connor, Judy Fiskin, Sydney de Jong, John McLaughlin, Frank J. Thomas, Audrey Wollen and Bedros Yeretzian, 2016–17. Digital image. Courtesy of Fiona Connor and Fredrik Nilsen.

Connor’s project undermines such a perception of the solitary artist and instead opens up a view of authorship that is inherently multiple and collective. In her own works, she replicates pre-existing objects that are often on the periphery of art making and extends a sense of authorship to the makers of the found objects and the contexts from which they were extracted. Her collaboration with Nilsen and the other artists in Ma can be seen as “play, activity, production, practice,” in which reading and writing collapse into “a single signifying practice.”29 Nilsen made the documentary photographs of Ma, and Connor has provided the captions for the photographs reproduced here. Who is framing whom? Whose work are we seeing? This blurring of boundaries—spatially, temporally, and conceptually—and the movement from object-based work to collectively authored text, understood CM dynamically in the present tense, characterizes the project set into motion by Connor.

By not reifying the work as an object, Connor’s project carries out one of McLaughlin’s essential goals. In an interview, McLaughlin explained: “The response that I would hope a viewer would get—and this is a very critical thing—is that he is supposed to respond to the wonder of the omission of an object. When you look at a painting with an object in it, you assess it by its value as an object. So I take the object out and you’re in a position to worry about yourself, not whether this artist was a good one or is telling you anything worthwhile.”30

Elsewhere, McLaughlin wrote, “Art is not in the canvas but in the mind of the beholder,” which seems akin to Barthes’s declaration that “a text’s unity lies not in its origin but in its destination.”31 In her ongoing project, Connor situates her work in proximity to the works of others in order to create a kind of (art) historical “text” that unfolds into the future, waiting to be received.

Kavior Moon is an art historian and writer living in Los Angeles. She teaches at the Southern California Institute of Architecture.