documenta fifiteen: Britto Arts Trust, ছায়াছিব (Chayachobi), 2022. Installation view, documenta fifteen, Kassel, June 18–September 25, 2022. Photo: Nicolas Wefers.

If the reported statements of German officials are to be believed, rising antisemitism, amounting to five incidents per day in 2022,1 can be blamed in part on contemporary art from Asia.2 Coverage of the opening of documenta fifteen in Kassel in June of that year revealed that many German critics and politicians were not prepared for the violent antisemitism of their own past and present to be reflected back at them through a postcolonial funhouse mirror. The initial wave of outrage was provoked by a twenty-year-old painting, by the Indonesian punk art collective Taring Padi, that regurgitated entrenched European antisemitic tropes in a misguided attempt at political critique. Removing this painting did little to stop the criticism, including from artists who withdrew their work in protest. At the Berlin Biennale, French artist Jean-Jacques Lebel’s installation of rephotographed images depicting the atrocities committed by US soldiers at the Abu Ghraib prison attempted to draw comparisons between neoliberal imperial violence and Nazi atrocities but only succeeded in retraumatizing fellow artists who were survivors of the American occupation in Iraq. Here, the Biennale refused to remove a work even after artists and one of the curators withdrew.3 In both cases, the response from politicians and journalists seemed driven more by controversy than by ethics, and the media reaction to both exhibitions made clear that globalism as a value and a framework for contemporary art is threatened by the same nationalist political forces that are challenging democracies around the world. As a result, the shortcomings of “inclusion” as a strategy for cross-cultural integration in the arts were laid bare.

While documenta fifteen was organized around globally networked intentional communities of art practice, the Berlin Biennale treated artworks as forensic evidence of historical and present-day crimes. The exhibition in Kassel imagined postcolonial futures of mutual aid and sharing, while the exhibition in Berlin took a darker view anchored in state surveillance and imperialist violence. Charges of antisemitism leveled at documenta and complaints by Iraqi artists of dehumanizing imagery in the Berlin Biennale undermined these progressive stances. In Kassel, these charges came in concert with physical attacks by the public against artists representing Palestinian, South and West Asian, and queer perspectives. What was revealed is twofold. First is the political effectiveness of conservative groups equating critique of the Israeli military state with antisemitism. Second is an unresolved conflict between, on the one hand, a European mode of symbolic response to calls for resolution of historical crimes, such as colonization and the Holocaust, that serves western liberals and, on the other, an increasing demand for material restitution and representation coming from artists and colonized peoples, specifically those from the Islamic world.

documenta fifiteen: Taring Padi, Bara Solidaritas: Sekarang Mereka, Besok Kita / The Flame of Solidarity: First they came for them, then they came for us, 2022, Installation view, documenta fifteen, Kassel, June 18–September 25, 2022. Photo: Frank Sperling.

The organizing principle of documenta fifteen was lumbung. As defined by ruangrupa, the Indonesian collective that curated documenta fifteen, lumbung “is the Indonesian word for a communal rice barn, where the surplus harvest is stored for the benefit of the community. The lumbung practice enables an alternative economy of collectivity, shared resource-building, and equitable distribution. Lumbung is anchored in the local and based on values such as humor, generosity, independence, transparency, sufficiency, and regeneration.”4 Dozens of collectives from the Global South were invited to put this principle into action. Many treated their installations in Kassel like offerings, such as Britto Arts Trust from Bangladesh, whose members cooked fresh vegetarian meals for the public on all one hundred days of the event. Ruangrupa’s invitation resulted in a global network of collectives, with hundreds of participating artists and thousands of art objects. The aesthetic was all-inclusive and maximalist, with banners and artifacts of political demonstrations in abundance at most venues.

The unorthodox layout of documenta fifteen incorporated typical venues, including the Halle and the Fridericianum, but also a disused bus and train factory, the Hübner-Areal, in Bettenhausen, East Kassel, a thirty-minute walk from the city center on the opposite side of the Fulda river. The program at the Hübner-Areal was centered on a film by Netherlands-based Argentinian filmmaker Sebastián Díaz Morales, whose contribution Smashing Monuments (2022) featured members of ruangrupa addressing famous public monuments in Jakarta in a one-sided conversation about rampant development, socialist ambitions, and the public’s desire for self-determination. The film could have been a manifesto for the exhibition, not least in its address to cultural artifacts that post-date European colonial ambitions. In the Halle, ruangrupa invited Wajukuu Art Project, from Nairobi, Kenya, to transform the 1990s-era steel-and-glass facade into a Global South pavilion using corrugated tin and thatched straw grass. Oil paintings were hung on top of a tin skin in the Halle’s front gallery, while freestanding wire and wood sculptures by Wajukuu artists filled the space. Both of these artistic gestures signaled a shift in perspective away from European values and priorities such as individual authorship and monetary value.

Wajukuu Art Project, Wakija Kwetu, 2022. Installation view, documenta fifteen, Kassel, June 18–September 25, 2022. Photo: Nicolas Wefers.

About documenta fifteen nearly everything is now in question but this: the Taring Padi installation People’s Justice (2002) made use of antisemitic visual tropes. Documenta’s directors have reason to be anxious about antisemitism, both because of the recent upswell in violence in Germany that mirrors a larger fascistic turn across the globe, and because Germany is still in a reckoning with the sins of its Nazi past. Historically, documenta has been a site for reconciliation between Germans who participated in perpetuating the racial violence of the Shoah and those who experienced it. Founded in 1955, in the aftermath of the Second World War, the original founders of documenta included several former Nazis,5 and the first iteration included hardly any artists of Jewish origin. Joseph Beuys, whose work was included in the 1972 and 1982 editions and whose radical pedagogy paved the way for ruangrupa’s discursive experimentation, was a former Nazi radio operator and a graduate of the Hitler Youth.6

Jewish artists have been better represented in recent editions, notably Michael Rakowitz’s installation in 2012, which drew parallels between the German Holocaust, the destruction of Kassel by Allied bombs, and the more recent purging of Jewish communities and heritage in Iraq. That edition also included a historical installation of drawings by Charlotte Salomon, a German-Jewish artist who was killed at Auschwitz in 1943. Documenta’s political value, and to a large extent its programming, has been rooted in atonement for German crimes within Europe to the exclusion of crimes abroad, a position that was challenged first by Okwui Enwezor’s documenta 11 in 2002. Enwezor was the first non-European director of documenta and the only director of color until the appointment of ruangrupa. dOCUMENTA (13), in 2012, and documenta 14, in 2017, both attempted to further the redistribution of attention and resources away from western Europe by mounting parallel exhibitions in less resourced cities, beginning with Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev’s dOCUMENTA (13) in Kabul, Afghanistan, and continuing when Adam Szymczyk and team expanded documenta14 to Athens. Both partner cities had borne the brunt of neoliberal failures: Afghanistan was then weathering a capricious and doomed US military intervention, while Greece was only beginning to recover from financial collapse brought on by the pressures of globalization.7

Trampoline House, Castle in Kassel, 2022. Installation view, documenta fifteen, Kassel, June 18–September 25, 2022. Photo: Frank Sperling.

After documenta 14, two troubling developments foreshadowed the present controversy. In September 2017, the German newspaper HNA accused the organizers of $8.3 million in cost overruns, which were attributed to the Athens expansion.8 In November, documenta’s managing director, Annette Kulenkampff, resigned her post in response.9 Later, in October 2018, Kassel authorities secretly removed Olu Oguibe’s celebrated Monument for Strangers and Refugees (2017) from its center-city Königsplatz location, ultimately reinstalling the work in a less visible spot on the Treppenstraße in April 2019.10 These machinations came to mind again in July 2022 when Sabine Schormann, the director general of documenta fifteen, resigned in response to the antisemitism charges.11

In June, the backlash landed on Taring Padi. The Indonesian anarchist collective created People’s Justice twenty years ago in Yogyakarta. An eight-meter-high painted banner mounted on a scaffold in the Friedrichsplatz, the work had an overstuffed, cartoonish aesthetic characteristic of a politically motivated group of students making collective art. Hundreds of caricatures fill the painting; two include iconography that can be identified as Jewish. The work was installed a day after the exhibition’s opening and removed two days later. Taring Padi issued a statement that fell short of an apology, asserting that their work had been misunderstood.12 Eyal Weizman’s assessment of People’s Justice aptly describes their approach and their problematic imagery:

As agitprop, People’s Justice isn’t complex. On the right are the simple citizens, villagers and workers: victims of the regime. On the left are the accused perpetrators and their international accomplices. Representatives of foreign intelligence services—the Australian ASIO, MI5, the CIA—are depicted as dogs, pigs, skeletons, and rats. There is even a figure labelled “007.” An armed column marches over a pile of skulls, a mass grave. Among the perpetrators is a pig-faced soldier wearing a Star of David and a helmet with “Mossad” written on it. In the background stands a man with sidelocks, a crooked nose, bloodshot eyes and fangs for teeth. He is dressed in a suit, chewing on a cigar and wearing a hat marked “SS”: an Orthodox Jew, represented as a rich banker, on trial for war crimes—in Germany, in 2022.13

Weizman goes on to say that Taring Padi initially claimed a culturally specific reading of the work, in which the antisemitic tropes had been transposed by European colonizers onto people of Chinese origin. As Weizman notes in his excellent analysis, this response was insufficient.

A disproportionate amount of attention has been focused on People’s Justice, given its brief tenure on display, but Taring Padi was well represented even without this work. Another work by the group, Bilik Interactive (2002–22), remained on view in East Kassel, an industrial and immigrant-rich area of town into which past documenta visitors have rarely ventured. Cardboard silhouette puppets created through community-embedded workshops in Germany, Indonesia, Australia, the Netherlands, and the United States depicted Indonesian freedom fighters and resistance figures. Inside the Hallenbad Ost, the Bilik Archives (2000–22) told a more comprehensive story of Taring Padi’s formation and their resistance to the Suharto regime. The two installations were materially similar, employing caricature forms on cardboard cutouts held together with tape in a manner that defied institutional expectations of an archive. The works in Bilik Interactive were staked into the lawn, with viewers able to walk in their midst and potentially seize and carry them as signposts in an impromptu protest. Bilik Archive comprised banners, paintings, and drawings, with a video documentary that contextualized Taring Padi’s emergence from within a poor community of anarchists and punks.

People’s Justice was not the only controversial work in documenta fifteen. The exhibition included numerous artists of Arab origin who expressed outright solidarity with the Palestinian people. The artists’ perspectives ran afoul of a 2019 German law that defines any endorsement of the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions Movement against Israel as an act of antisemitism, and thus illegal.14 This law was used to challenge The Question of Funding’s documenta installation, which examined the financial constraints under which the Palestinian freedom movement operates. Throughout a subterranean network of rooms in the Werner-Hilpert-Straẞe 22 building complex, The Question of Funding installed comics, posters, and graphic illustrations on tablets. The works detailed dependencies between creative labor and systems of oppression that are reinforced through currency and financial systems. The installation emphasized ways to circumvent these circumstances as stateless persons. The group’s second installation, inside the Hübner-Areal, chronicled one artist’s difficulties in maintaining an art practice under Israeli sanctions in the Occupied Territories. Some group members’ association with the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center, a Palestinian organization whose namesake held antisemitic views, including Nazi sympathies in the 1930s, was enough to provoke ire. Vandals attacked the space designated for The Question of Funding’s installation a week prior to the exhibition opening, on May 28, leaving hate symbols, including the American slang term for murder, “187,” implying lethal intentions. Within a month of the opening, The Question of Funding cancelled their scheduled programming, and they departed Kassel two months earlier than planned.

The Question of Funding hosts Eltiqa, 2022. Installation view, documenta fifteen, Kassel, June 18–September 25, 2022. Photo: Nils Klinger.

Also subject to critique was Subversive Film’s Tokyo Reels Film Festival, which presented found footage from an archive of pro-Palestinian propaganda films produced in several countries in the Levant and Europe, as well as Japan, that were collected and preserved in Japan by members of a local Palestine solidarity group in the 1980s.15 The short silent film I watched, The Game (1973), by Iraqi director Shirak, spared no criticism of Israel’s military activities in the Occupied Territories. In the story, a group of Palestinian boys play at war, pantomiming fighting until one of them is killed by a wayward Israeli rocket. The loss of their friend radicalizes the children, and they take up arms as soldiers. As propaganda goes, it was effective. The one-sided narrative, in which the Israeli soldiers who launched the rocket are never seen, generates sympathy with Palestinians. There were no references to Jewish stereotypes, customs, or religious beliefs, or even to the existence of civilian Israelis, in the film I saw.

In September, a committee appointed by the documenta supervisory board and dubbed a “scientific advisory panel” found fault with ruangrupa’s inclusion of both People’s Justice and the Tokyo Reels films. Their statement reinscribed the 2019 law’s conflation of criticism of the Israeli government with antisemitic sentiment:

In the view of the Undersigned Members of the Panel, the “Tokyo Reels Film Festival” is the most glaring example of documenta fifteen’s bias with regard to the Arab-Israeli conflict which is dealt with by a comparatively large number of works. Almost all these works express attitudes that range from critically biased to decidedly anti-Israeli. These attitudes are reflected in the pictorial representations and statements, which can be judged as anti-Semitic according to commonly accepted criteria. This becomes particularly evident when the existence of Israel is questioned or denied in the works.16

The panel proceeded to criticize ruangrupa for failing to include commensurate references to the Jewish Shoah and Jewish perspectives on the Middle East. While it remains acutely necessary to remind Germans of the terrible cost of antisemitism, this criticism is misguided. Ruangrupa has deliberately decentered German actions and German narratives, including German wrongdoing, in order to foreground perspectives from the Global South that usually don’t command this many resources. This criticism by the panel seeks to restore a comfortable narrative of right and wrong on Eurocentric terms. Conflation of Jewishness and the Israeli state cast the pro-Palestinian perspectives of progressive Jews—such as Jewish Voice for Peace, who have supported the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions Movement—as antisemitic, flattening dissent within the Jewish diaspora in favor of alignment with a neoliberal political stance on Israel that, again, serves the interest of German diplomatic and economic policy first and foremost.

British Bangladeshi artist Hamja Ahsan’s comical lightboxes advertising imaginary halal chicken restaurants were placed at unexpected locations throughout the documenta fifteen exhibitions. Some contained references to Palestinian resistance, such as “PFLFC—Popular Front Liberation Fried Chicken.” Others allude to the imperial failures of the United States, such as “Kabul Fried Chicken—Graveyard of Empires.” In August, Ahsan was deemed too provocative to return to Kassel for scheduled live performances after he insulted German Chancellor Olaf Scholz on the artist’s personal Facebook page, calling him a “neoliberal fascist pig” in response to Scholz’s proposed one hundred billion Euro increase in German defense spending.17 Ahsan, a self-declared “shy radical”18 who sometimes operates similarly to an online troll, also made controversial posts using the term apartheid to criticize the Israeli state’s human rights record and generating inflammatory language online in the manner of a “flame war” on “WHITE Girl Boss Solidarity”19 in German cultural institutions.

Atis Rezistans | Ghetto Biennale, 2022. Installation view, documenta fifteen, Kassel, June 18–September 25, 2022. Photo: Frank Sperling.

Of the works in this documenta, a majority were collectively generated, many were shown while still in progress, and few adhered to marketable formats like painting, sculpture, and video, making this iteration a departure from the many biennials that feed directly into art fairs. This is another way that European audiences and their values for art have been decentered. The Finding Committee for the Artistic Direction of documenta fifteen, which consists of eight prominent global artists and curators and helped tap ruangrupa as the creative director, issued a response to the scientific advisory panel report in September. The committee defended both ruangrupa and the lumbung concept that anchors their decolonial rhetoric:

We reject both the poison of antisemitism and its current instrumentalization, which is being done to deflect criticism of the 21st century Israeli state and its occupation of Palestinian territory. At the same time, we embrace documenta fifteen’s pluralism and the possibility to hear such a rich diversity of artistic voices from across the world for the first time. We defend the right of artists and their work to rethink, expose, and criticize political formulas and fixed patterns of thought. We believe this right is something to be cherished by those in public life who make exhibitions like documenta possible.20

Lumbung emphasizes sociability, habitability, and collaboration while downplaying material or aesthetic value. Lumbung is social practice flavored with a Global South twist of politically selfsufficient collectivism—which ruangrupa terms the ekosistem. Hundreds of artists comprising over forty collectives from five continents filled the Fridericianum. Communications and broadcasts, food cultivation and preparation, new currency models, and kios (self-organizing kiosks) were some of the forms on display. New Delhi-based Party Office organized a subterranean nightclub with a BDSM theme. Several of the venues were in postindustrial spaces in East Kassel, far outside the traditional footprint for documenta. The Haitian collective Atis Rezistans created a Vodou-themed sculptural installation inside a church. Canvas domes housed sound installations and crafting programs. At the center of the Documenta-Halle was an active skate ramp. Here, too, were collapses: a hundred-day program of events was truncated when Party Office members were assaulted in Kassel in July,21 and Hito Steyerl withdrew her work in response to both the antisemitism charges and complaints by documenta staff of unsustainable working conditions.22

This last point is worth noting in light of documenta’s decision to invite artists to curate the exhibition, with administrative liaisons but no curatorial advisors to lend the kind of production and management expertise that is essential for a project of this scale and scope. Artists are increasingly being tapped to lead biennials in the role of “guest curator,” a position that already indicates institutional divestiture from the advocates and creative visionaries who make successful exhibitions work. In addition to choosing works for exhibition, curators also run interference, managing conflicts between artists and between artists and the public. These tasks are doubly difficult when the institution holds the curators at such a distance. Does the reliance on contract curators—often artists with limited institutional experience hired and managed by career administrators—reflect a conflicted desire on the part of the institution to both speak freely and control speech? In response to curator Jens Hoffmann’s 2004 e-flux project, “The Next Documenta Should Be Curated by An Artist,” we might now ask, “What Is a Curator Now That Documenta Has Been Curated by An Artist?” Artists often create immersive experiences that blur lines between reality and fantasy and tread in challenging areas of the human psyche. Within the parameters of their works, the systems and values of the outside world may be suspended. But within the walls of the institution, a politics exists that needs to be thoughtfully engaged. Ruangrupa asked powerful questions but frequently fell short of showing the artists they brought to Kassel in ways that left the artists feeling supported or granted visitors the benefit of a clear understanding of their practices. The situation begs a broader question: To what extent have institutions—as public sites of shared knowledge and collective organization—outsourced their core mission work, and to whose benefit?

Zach Blas, Profundior (Lachryphagic Transmutation Deus-Motus-Data Network), 2022. Installation view, 12th Berlin Biennale, June 11–September 18, 2022. Photo: Laura Fiorio.

One frequent criticism of documenta fifteen—that the artworks on view were provisional or unfinished—could not be leveled at the more conventionally objectbased and visually oriented 12th Berlin Biennale. Controversy was nonetheless a factor. Lebel’s appropriated photos of detainees being tortured by US military personnel at Abu Ghraib, a documented war crime, prompted withdrawals from Iraqi artists Sajjad Abbas, Raed Mutar, and Layth Kareem, whose work was displayed adjacent.23 These three artists were also included in documenta fifteen’s excellent “Sada [Regroup],” a presentation of films by Iraqi artists that was organized by curator Rijin Sahakian. Sahakian drafted an open letter to the Berlin Biennale curator Kader Attia and his team outlining the problems with their choice of including Lebel and explaining how his photographs aestheticize the violence visited on Iraqi citizens by American troops during the war. The withdrawals came after Attia (cosigning with Đỗ Tường Linh, Marie Hélène Pereira, Noam Segal, and Rasha Salti from the curatorial team) responded with a statement claiming a higher political value for the juxtaposition. “Let us show the colonial crime. Let us suffer from this vision of horror,” Attia and team intone, implicitly justifying these artists’ retraumatization “We will come out of it, if not grown, at least more human, having experienced, for a few moments, catharsis and the field of emotion.”24 If we give the curators the benefit of the doubt and assume that they do not actually wish to inflict suffering and visions of horror on artists and viewers who have had to flee war and persecution in their lifetimes, then we must assume that their focus is on a different viewing public. Sahakian’s response announcing the withdrawal characterized the curators’ statement as “instrumentalization of our work and our identities as Iraqi.”25 Their suffering, in this context, is simply further proof of the West’s collective crimes in a court of popular opinion masquerading as an art display.

If ruangrupa’s socially engaged curatorial praxis derives from a nongovernmental organizational model of micro-investment as international development, then Attia’s curatorial model comes from the police: the evidence locker. This works effectively when the setting is the Stasi Museum, where artworks by Haig Aivazian, Zach Blas, and Hasan Özgür Top are interspersed with historical artifacts documenting the overwhelming surveillance state operated by the former East German regime. (One work by Omer Fast was sited in an actual locker, although the ongoing European heat wave this summer had caused the electronic components inside to overheat and fail when I visited.) The artwork-as-proof approach makes far less conceptual or aesthetic sense in a large contemporary art museum like the Hamburger Bahnhof or the KW Art Institute, where the works are in dialogue with art history and museums, sites of ongoing state power and social control. In these hallways, images of atrocities committed in the name of power are late entries in a catalog of historical crimes. Why single out one atrocity for appropriation—Lebel’s Abu Ghraib grotesque—while soft-pedaling others? Egregious, yes, but not especially fresh. A bigger crime in terms of everyday, current impact could be said to be the eviction of migrant and destitute families from a vacant lot in suburban Paris, documented in the work of PEROU—Pôle d’Exploration des Ressources Urbaines. Their video, displayed on a small and unassuming screen, is a highlight of the Hamburger Bahnhof installation yet is afforded much less real estate than Lebel’s tone-deaf installation. The discrepancy in scale and attention between these two works suggests a desire to serve convenient outrage at US imperialist ambitions while downplaying European complicity in human suffering taking place right now.

Outside Lebel’s gallery, a sign installed in response to the Iraqi artists’ withdrawal advises, “Please do not enter the room if you have experienced racial trauma or abuse, as you might be triggered.” As a critic, this warning put me in an impossible position. My responsibility to my reader, as a writer, is to see, evaluate, and critique every artwork on display. My responsibility to myself, as a human in a racially marked body, is to shield myself from needless trauma anchored in my racial identity. The sign suggests that those who are most affected can simply opt out, while assuming that the majority of gallery visitors would elect to opt in to viewing an installation that can best be described as social pornography—an indulgence of our worst tendencies to delight in the suffering of others and justify it as truth-telling.

Mathieu Pernot, photographs from the series Les Gorgans [The Gorgans], 1995-2015. Installation view, 12th Berlin Biennale, June 11–September 18, 2022. Photo: Silke Briel.

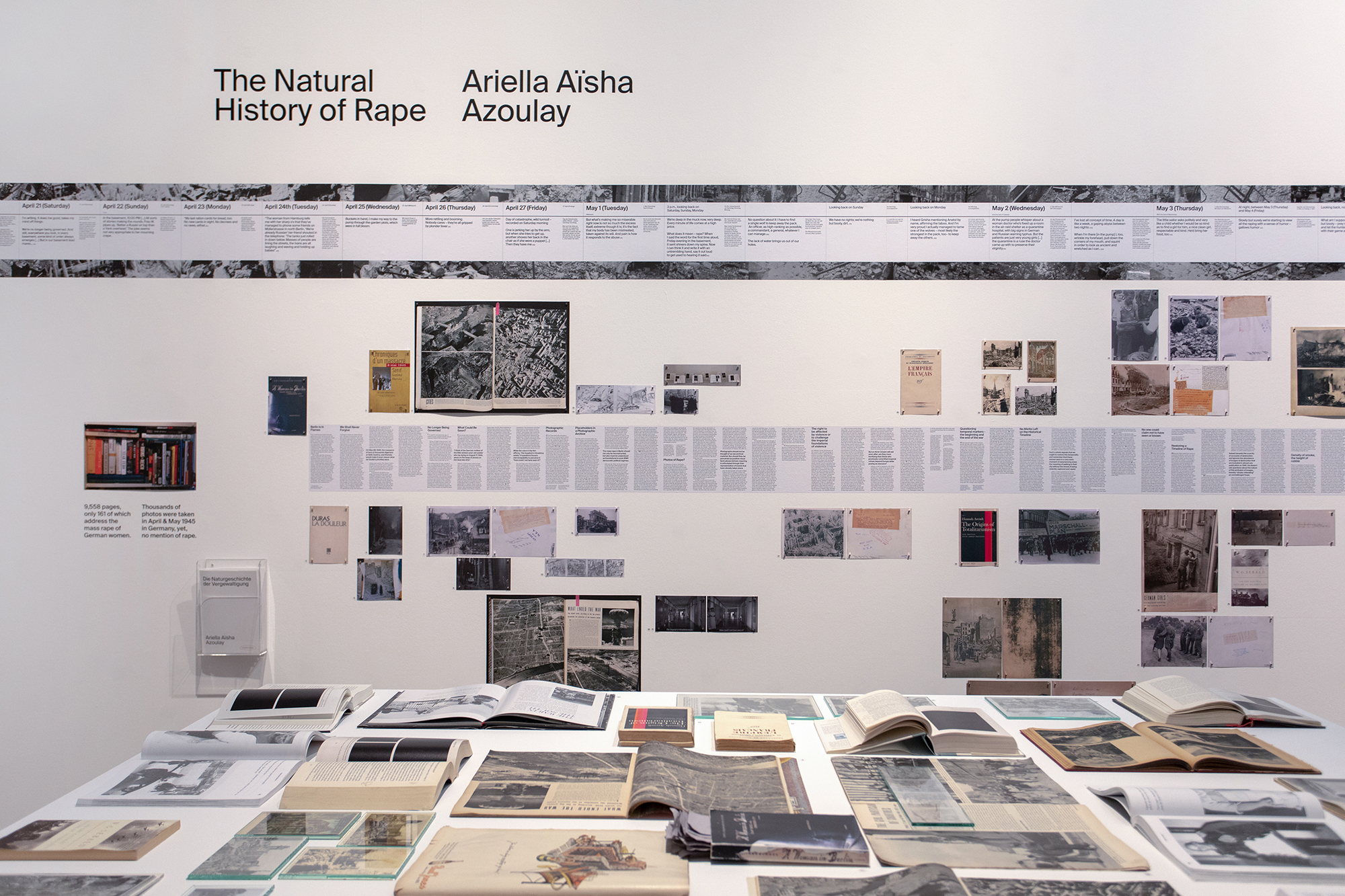

Also at the KW is an installation by philosopher Ariella Aïsha Azoulay consisting of archival photographs of women in postwar Germany. The work delves into the aftermath of Russian occupation, describing rampant sexual violence in the former East Germany for which there was no documentary evidence and no legal accountability. Azoulay’s chronicle of German women’s suffering helped cement my understanding of Attia’s curatorial approach as legal discovery, in which one attempts to use the sins of the past to indict the present in a connect-thedots fashion. In The Natural History of Rape (2017/22), Azoulay strives to recreate a historical record of crimes that were never documented by the camera by using materials that do remain in the archive to frame the gaps. In Azoulay’s influential book The Civil Contract of Photography, which is theoretically grounded in her consideration of Palestinian self-rule, she develops a discourse of rape as a violence that reinscribes women’s status as extralegal beings, unprotected by the state. The German women raped by Russian soldiers after the war exhibit “susceptibility to a particular type of disaster” that “does not tend to generate an examination of their civic status” as women.26 Captive populations, which can include minoritized groups like African Americans, German Turks, and Palestinians, alongside women, LGBTQIA+, the elderly, and children in the dominant group, are uniquely vulnerable to war crimes, because they are already excluded from systems of justice. No examination, no outcry on the part of indignant authorities will be forthcoming. Azoulay’s work in Berlin was haunted not only by the unseen crimes it details but also by the specter of the current Russian invasion of Ukraine.

On the heels of documenta, the Orange County Museum of Art, in Costa Mesa, California, disinvited artist Ben Sakoguchi from participating in the California Biennial 2022: Pacific Gold on the basis of a swastika in his painting of the Japanese Emperor Hirohito—a Nazi ally and an agent of genocide in Asia—whom the work is intended to critique.27 Sakoguchi’s censored painting is a critical representation of Asian history by a storied Asian American artist. Its fitness for exhibition was judged solely on the basis of its relationship to European history.

The California Biennial’s decision, like the findings of documenta’s scientific advisory panel, smells of protectionism for the sensibilities of patrons above all else. Can western art institutions reconcile that influence with growing support for decolonization among artists and their public? Artists based in the United States and Europe increasingly endorse Palestinian independence and express solidarity with victims of imperial violence. How can we preserve their right to tell their own stories in a deeply conflicted culture? The established role of publicly funded museums has been as a site of power for the state and, increasingly, they play a similar role for financial elites. As such, museums have overwhelmingly profited from the colonizing actions of western governments, such as the United States, Israel, and Germany.

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, The Natural History of Rape, 2017/22. Installation view, 12th Berlin Biennale, June 11–September 18, 2022. Photo: Silke Briel.

German biennials are underwritten with public funds, and as such they are promotional devices for state policy. In documenta fifteen, artworks by Kurdish Australian artist Safdar Ahmed and the Moana Oceanic arts collective FAFSWAG, from Aotearoa, New Zealand, were installed adjacent to a gallery displaying a scale model of the city of Kassel in ruins after the Second World War. Displays addressing Nazification and the Holocaust were present, but nothing packed the emotional punch of that model, which perennially centers the pain of Germans over that which they inflicted. The backdrop of German cultural institutions at both the 12th Berlin Biennale and documenta fifteen helped to contextualize the artworks on view within the larger narrative of how Germany sees itself, eighty years after the end of the war.

Two Berlin Biennale exhibitions at the Akademie der Künste struck a more dreamlike tone. The Hanseatenweg show featured a standout work by Tuấn Andrew Nguyễn, My Ailing Beliefs Can Cure Your Wretched Desires (2017). In Nguyễn’s film, the spirit of the last Javanese rhino describes the poaching that led to its extinction in 2010, while a fifteenthcentury sacred turtle listens empathically. This two-channel work is visually stunning and brimming with a barely concealed rage at the state of the planet, the ecosystem, and human behavior. It is one of the few works on view in the biennale that speaks to survivors of colonialism, rather than about or for us.

Taking a cue from Nguyễn, decolonization means deemphasizing the suffering of Europeans, even minoritized ones, in favor of the needs and concerns of Indigenous and displaced communities that precede colonization. Moreover, it means deprivileging human perspectives to consider the needs of non-human species and ecosystems. Based on the responses to documenta fifteen and the Berlin Biennale, most critics were comfortable with presentations that critiqued European and American violence and domination and far less comfortable with presentations that ignored Euro America as the source of new ideas in favor of other, more sustainable paths forward. Attia tried to follow the rules by building a case with evidence that showed Euro American audiences their complicity in the crimes of the present. Ruangrupa’s great transgression may be that they never tried to make their documenta legible to western art audiences at all.

Anuradha Vikram is a writer, curator, and educator based in Los Angeles. They are a member of the editorial board of X-TRA, co-curator of the 2024 Portland Biennial, and guest curator of the 2024 Pacific Standard Time Art and Science exhibition Atmosphere of Sound: Sonic Art in Times of Climate Disruption, hosted by UCLA Art|Sci Center.