By most accounts, the Mike Kelley retrospective exhibition at MoMA PS1 was a resounding success.1 The old public school building seemed the perfect environment for Kelley’s work, given its themes and iconography, and it was always packed. There were crowds of young people, more than a few in elaborate costumes; art students, or people who fit that description; and families with children in strollers. One hopes the kids were young enough not to know what they were looking at, but with Freud and Kelley both, it is likely that no child is ever young enough not to be traumatized, if only after the fact. Every time I went there were lines waiting to get into the gallery that housed his Deodorized Central Mass with Satellites, (1991/99); it’s not clear to me why that work in particular, but it became a popular Instagram and Tumblr image and blog entry. The Brooklyn Rail’s reviewer calls the work “iconic,” though I’m not sure how it got to be, or even whether it was before PS1. The atmosphere was oddly joyful or, maybe fittingly, carnivalesque. I don’t know what people made of the work, but there was palpable good will and a real respect for how hard Kelley worked, and how much different work he produced. As one blogger put it: “We all have the same 24 hours in a day and I have to strive harder to make the minutes count.” “It’s a testament to how much productivity and creativity can come from a mind that is challenged and passionate about their craft. Hoping to gain more of that perspective this year.”2

Walking through the exhibition I felt myself quite distant from the crowds (a conventional modernist feeling, I know), wondering what they got from the works assembled, beyond lessons in productivity, time management, and Goth punk sensibility; what they took in or imagined it was about. You might hear this as elitist and pedantic, given that I am presuming a right, or at least a righter, way to think about the work. Maybe so. I do have some sense of the interpretative horizon of Kelley’s work and I’ve written a lot about at least some aspects of it. But my estrangement was not only “critical distance” or aristocratic distaste; it was also affective, and not about the crowd at all. PS1 was very much a haunted house for me, as it was for many who knew Mike, and if the show was affirming, it was also, at least for me, sad and angering. Embittered, maybe, but whether that applies to me or to Mike, I’m not sure. Therapeutically, it might make most sense for me to write about the work I feel closest to—even if it were merely to lament that those early works weren’t, and maybe couldn’t be, adequately represented. Certainly it would be difficult to draw together all of the drawings Kelley made for Monkey Island (1982–83) or The Sublime (1984) and even then the performances themselves would be missing. As Kelley says to Eva Meyer-Herman in the catalog’s interview, “You’re never going to see my shows again as they originally were. Viewers of a survey exhibition have to realize that they’re only seeing a kind of series of fragments of a whole.”3 While whole rooms are devoted to the initial exhibitions of Monkey Island, The Sublime, and Plato’s Cave, Rothko’s Chapel, Lincoln’s Profile (1985), the assembled drawings can only fill so much space—The Sublime feels particularly sparse—and it might matter that the spaces in which they were originally exhibited were relatively modest, certainly smaller than the spaces in which Kelley’s work has been seen for the past decade and a half.

Mike Kelley, Day Is Done, 2005–06. Installation views in Mike Kelley at MoMA PS1, 2013. © 2013 MoMA PS1. Photo: Matthew Septimus.

Almost all of Kelley’s works are partial in some sense; almost all are parts of series or sequences related to other works and other aspects of his research. Kandors (2007) and its related works and Day Is Done (2005) take up the most real estate at PS1, and even they are only partial. Kandors as a project spans more than a decade, as do the Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstructions that form the spine of Day Is Done; PS1 showed only seven of the twenty-five installations included in Gagosian’s Day Is Done in 2005. But where the galleries of early work felt fragmentary, Kandors and Day Is Done felt sprawling—Day Is Done occupied the largest single gallery on the second floor and the most uninterrupted floor space overall. Kandors filled eight rooms, an entire wing on the first floor. This appropriation of real estate was not lost on the New York press or on social media. Holland Cotter put it most generously (as he is wont to do) in the New York Times. Of the Kandors works, he writes, “they’re uncharacteristic of Kelley’s art overall…. Like the wildly elaborate Day Is Done, they date from after the time Kelley signed on with the Gagosian Gallery in 2005. He was now a star with a big budget, and the work suddenly looks expensive, machine-tooled, overproduced. The Kandors have the luxury-line gloss of Jeff Koons junk art. What saves them is that they have Kelley’s history behind them.”4 Acquaintances on Facebook were not so kind: “Mike did not make much very good work for the last fifteen years. It just feels like production to me, but with very little soul.” I want to find a way to write about Kandors and the Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstructions, precisely because the works are so unlovable, so slickly realized; the installation so cacophonous and large. And, to be blunt, I want to write about them here because of their bleakness.

PS1’s deliberately non-chronological installation may have made Kelley’s history hard to grasp, but in an interview in the Brooklyn Rail, Cary Levine made at least some of the history Cotter was referring to clear. Levine is the author of a recent book on Kelley, Paul McCarthy, and Raymond Pettibon, and he links his discussion of Kelley’s retrospective to McCarthy’s WS (2013).5

It was the same kind of response to Kelley’s Day Is Done (2005), that it was hyper-indulgent, as though the artist was not aware of what he was doing, as though it was devoid of self-critique. Moreover, such criticisms preclude an engagement with the specific subject matter of the works in question. No one said, “He’s reproducing these high school musicals as scenes of trauma linked to both mass media and pedagogic institutions, and this is consistent with virtually his entire oeuvre.” Both Day Is Done and White Snow are culminations of 30 years of work. This doesn’t mean they’re above criticism, certainly not, but it’s more than that these artists simply got a lot of money and decided to blow it out and have a big circus.6

I would like to see Day Is Done and Kandors as continuous and consistent, as Levine suggests, but I am wary of saying that it has always been about “trauma linked to mass media and pedagogic institutions,” or even that there have always been such themes. The methodological problem with themes, whether trauma in Levine’s presentation or home in Holland Cotter’s (“Home, in one form or another, is what Kelley kept coming back to”), is not only that they are potentially reductive readings, but also that they are, like Kelley’s Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstructions, symptomatic ones: readings projected from the present onto the past that allow us to imagine that these meanings were always there, written from the outset, both causal and caused. And there’s no question that Kelley’s own reworking of his origins, from Educational Complex (1995) on, encourage such readings.

Levine refers to Kelley’s “scenes of trauma” as “subject matter,” a term that hearkens back to Meyer Schapiro’s important and cautionary distinction between subject matter and “object-matter,” a distinction given voice by Barnett Newman: “Most people think of ‘subject-matter’ as what Meyer Schapiro has called ‘object-matter.’”7 That is, they confuse what a work of art depicts—its subject matter in the conventional sense—with what it is more deeply about, its content or its meaning. It’s not entirely clear how Levine might mean the term, but it is clear that trauma was Kelley’s “object-matter” from the 1990s on, and he was very smart—that is to say distancing and ironic—about it. He knew what his work was about, and what he was up to. Nearly everyone who has written on Kelley’s work since the mid 1990s has recounted how he took up the issues of repressed memory and victimhood in conscious and quite tactical response to the misinterpretations of the earlier craft works. Indeed, Kelley, by far his own best critic, told the story more than a few times: “I had to abandon working with stuffed animals for this reason. There was simply nothing I could do to counter the pervasive psycho-autobiographic interpretation of these materials. I decided, instead, to embrace the social role projected on me, to become what people wanted me to become: a victim.”8 A role had been projected onto him as though he was one of the figures in a high school yearbook picture, and he took it on. Or, as he said, “I am often working ‘in character.’”9 Given that trauma was his primary—I would say sole—subject matter from the mid 1990s on, the question of the last work might be if and when did it become his content.

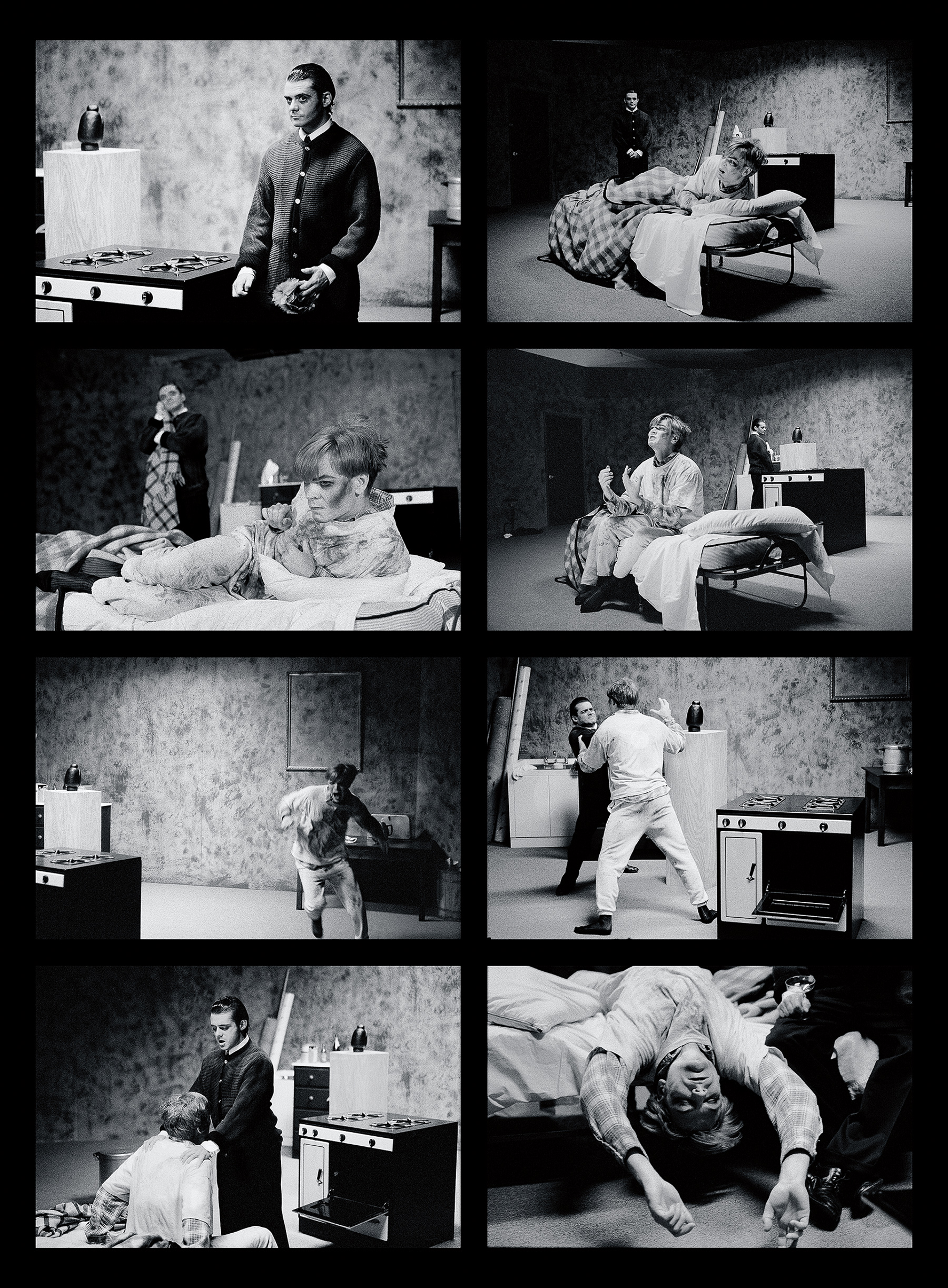

Mike Kelley, production still from Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction #36 (Vice Anglais), 2011. Video, color/sound, 24:15 min. Photo: Jennie Warren. Courtesy Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. © Estate of Mike Kelley. All rights reserved.

Were I to pick a recurring theme, a motif Kelley returned to throughout his career, it might be caves, but its recurrences mark the ruptures more effectively than they do the continuities. Caves are there near the beginning, in Plato’s Cave, Rothko’s Chapel, Lincoln’s Profile, and at the end in the Kandors. (And we could backdate them still further if we broaden the subject to include the primordial landscapes of Meditation on a Can of Vernors [1981], Three Valleys [1980], and Monkey Island.) The cave is a nearly perfect image, subterranean, dark and dank. And it comes to Kelley readymade, already fully written in myth and folktale as the female body, as the unknown, as death. It was an important figure for surrealism, certainly, the very image of the unconscious, and Kelley found it close at hand. Introducing the American painter Gerome Kamrowski to a Paris audience in 1950, André Breton wrote, “Of all the young painters whose evolution I have been able to follow in New York during the last years of the war, Gerome Kamrowski…was the only one I found tunneling in a new direction.”10 Breton links the painter, then teaching in Ann Arbor, to a remarkable group of artists, “Picasso, Chirico, Duchamp, Kandinsky, Mondrian, Ernst, Miró,” as a way to insist on his originality: “All that the latter have bequeathed to Kamrowski is their pickaxe and lamp.” Two decades later, Kamrowski would be Kelley’s favorite teacher at the University of Michigan, but Kelley’s caves are quite different from his teacher’s surrealist tunnels with their phosphorescent lights and aquatic, spectral depths. His are inhabited not by Theseus or the Minotaur but by Nazi spies and Superman and by the legendary city of Kandor.

Shrunken and bottled, vacuum sealed in time and space, Superman’s hometown Kandor is a perfect metaphor, or perfectly metaphorically available. It “functions metaphorically as a symbol of his alienated relationship to the planet where he now resides,” Kelley explains. “Kandor now sits, frozen in time, a perpetual reminder of his inability to escape the past, and his alienated relationship to his present world.”11 Here in his Fortress of Solitude, Superman is the artist, and an insistently romantic one at that, reciting selections from Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, which is, in case we’ve missed it, where Kandor is housed. Kelley’s Kandors works are based on the renderings of generations of Superman’s illustrators; some bottles are squat, others narrow and tall. Sometimes the city is quite crystalline and detailed, other times amorphous and sketchy. There was no decided image for the city, as there was, say, for Superman’s costume; rather it was often set decoration, overlooked, and site for a certain creative license. That too makes it symptomatic; a metaphor hidden in plain sight like the purloined letter. As Kelley notes, complaining to Meyer-Herman:

With the Kandors series, people can’t seem to get past the Superman reference. Apart from a few metaphors that interest me, I’m not particularly interested in Superman comic books…. My primary interest was that each rendition of Kandor was completely different, and that allowed me twenty quite different formal variations of the city…. But, instead, it’s more “bad boy” crap. “Mike Kelley is a nerdish comic book fan.” That’s simply not true, or what that series is about.12

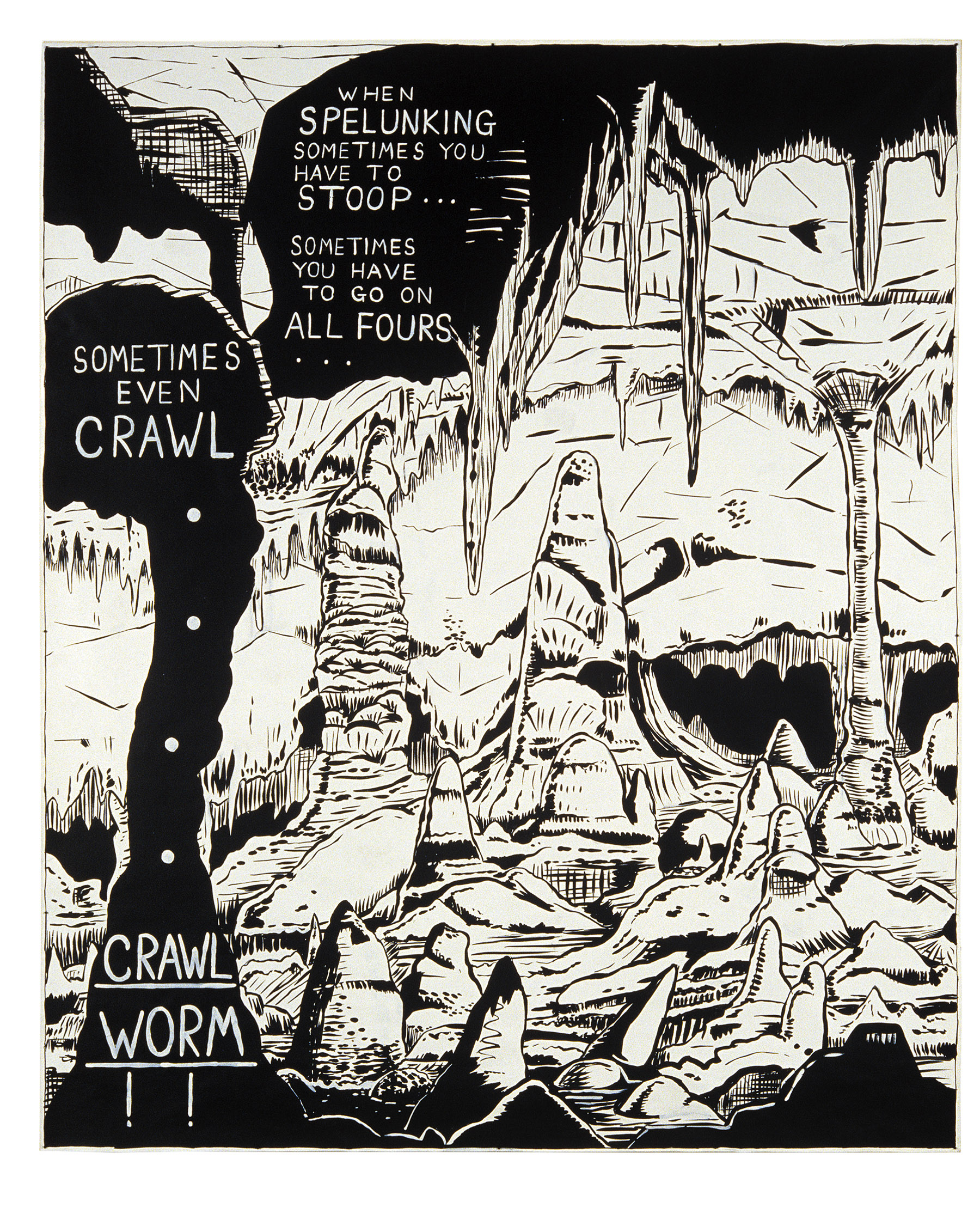

Perhaps aboutness is the issue, how tightly the metaphors are constructed and how clearly Kelley wants them to read. One entered the installation of Plato’s Cave, Rothko’s Chapel, Lincoln’s Profile at Rosamund Felsen in 1985 on all fours, crawling under a large drawing of a cave, and the command “Crawl worm.” But when Meyer-Herman asks, “What would you say Plato’s Cave is about?” Kelley responded, “Almost nothing! It’s about a certain set of cave references and other kinds of references related to my research.”13

Mike Kelley, Exploring, 1985. Synthetic polymer on paper on canvas, 76 1⁄2 × 64 inches. Courtesy Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. © Estate of Mike Kelley. All rights reserved.

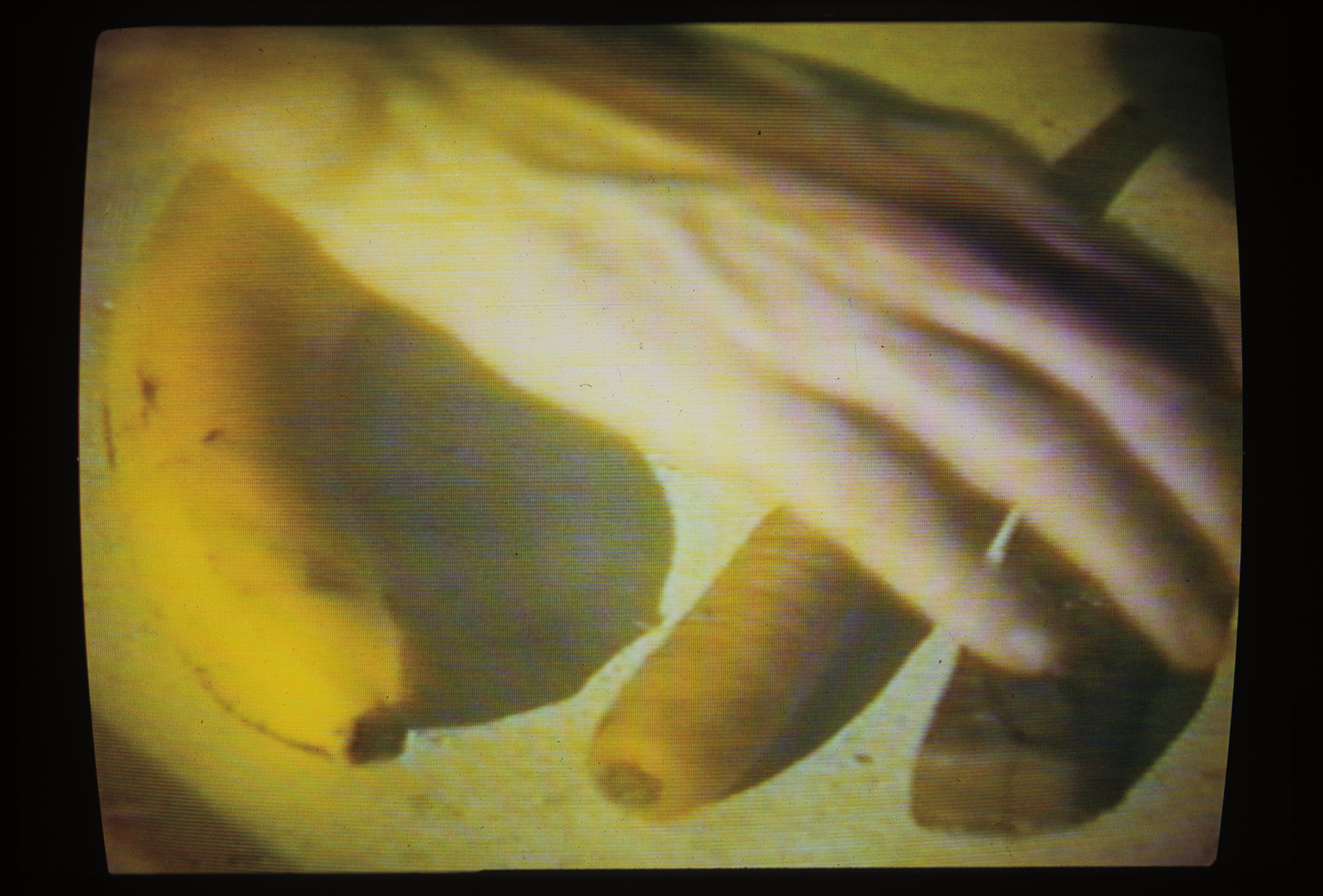

In 1986, Dan Cameron titled an essay “Mike Kelley’s Art of Violation,” pointing to the artist’s comic anti-formalism and his aesthetic border crossings.14 With Day Is Done and the Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstructions, and with the Kandors in their exploded sense, the violation is more direct and literal, indeed quite specific. Kelley’s works have long been driven by sexual energy, scatology, and shame, but they are not all about sex and shame in the same way. In the later works there is no sexuality without violation, no pleasure that does not depend on the humiliation of the self or another, no model that is not sadomasochistic. The violations have no catharsis, no sense of release. There is no longer, as in the early performances, a belief in play of language or the talking cure. However talky some of the Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstructions might be, they are insistently, relentlessly scripted, the script moving only in one direction—and only ever thematically, dramatically. Shame, remorse, the Freudian family romance, homosexual attraction, and abduction might be themes shared between Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction #1 (A Domestic Scene) (2000), installed at MoMA on 53rd Street in conjunction with the show at PS1, and The Banana Man (1983), the earliest video in the exhibition, but Kelley’s scripts and his visuals are quite different. A Domestic Scene is scripted with and after Sylvia Plath and Saul Bellow (in particular, Bellow’s The Victim), and acted as melodrama; The Banana Man is more clearly a performance than a play, and far closer to poetry than to melodrama: a recitation of linguistic, visual, and spatial metaphors that hover around the sexual and the religious. (And it was a pleasure to hear Kelley’s voice intoning it.) It is about sexual seduction and loss of self, perhaps, but there is not yet a perpetrator or penetrator, and not yet a victim. There is a structural homophobia in the later work, in the stories of Timeless/Authorless and the Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstructions. That is the calculus of victimization they have inherited from abuse stories and their formulas. And from the “victim” culture that Kelley cannibalized: all sex is degrading, and degradation comes only from behind, only anally. The corncob that appeared as part of his Pagan Altar in 1989 and that adorns the sides of More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid and the Wages of Sin (1987) now only does one thing.

Mike Kelley, Untitled (Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction #1 [A Domestic Scene]) (detail), 2000. One of five black and white photographs; parts 1–4: 37 × 27 1⁄2 inches each, framed; part 5: 37 × 32 inches, framed. Courtesy Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. © Estate of Mike Kelley. All rights reserved.

Mike Kelley, still from The Banana Man, 1983. Video, color/sound, 28:15 min. Courtesy Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. © Estate of Mike Kelley. All rights reserved.

I tried not to end my essay for the catalog for Mike Kelley’s exhibition at the Weils Centre d’Art Contemporain in 2009, and my discussion of Black Out (2001), his large-scale photographs of a trip down the Detroit River, with the words “Fade to black.” I got there and pulled back: “Fade to black is not the way to end. It is, on the one hand, too neat and expedient, and on the other it suggests a kind of nihilism. Kelley insists that he is a poet rather than a nihilist.”17 Now I am not so sure. I shared an office with Kelley in 1982–83, when we were both adjuncts at the University of California, Los Angeles. His class reading list that fall included Ernst Kris and Otto Kurz’s Legend, Myth, and Magic in the Image of the Artist and Kris’s own Psychoanalytic Explorations in Art, with its essays on caricature and “a psychotic sculptor of the eighteenth century,” as well as another essay on the image of the artist in ancient biographies—hero stories of the artist as Superman, the theme Kelley circles back to in Kandors. “[T]he fact that Superman is an alienated being saddled with the responsibility of caretaking his traumatic past—represented by the city of his birth in a bottle—is somewhat like my own Educational Complex.”18 Kelley was well aware of the constructedness of the image of the artist and the craft of identity formation. This, too, is about working in character. Kris writes: “One gains sometimes the impression that the actual behavior of one or another of the famous artists of the time has been used as a prototype, frozen into a formula which is being handed down as such to succeeding generations.”19 I had copies of those books on my shelf as well that semester, for an essay I was writing in the office that year on how the artist was represented—was typecast—in The Rothko Conspiracy, a BBC docudrama about Rothko’s death and the aftermath of his estate. I quoted those lines above and railed against the producers’ insistence on engaging in “pathographic analyses….on seeing the artist’s life and work as one and the same thing.” “The Rothko Conspiracy,” I wrote, “offers [his paintings] only one meaning….they can only be seen as suicide notes.”20I would like to offer a similar caution here, but whether or not trauma was the content of Kelley’s work before January 2012, it seems unavoidably so now.

Mike Kelley, Untitled (Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction #1 [A Domestic Scene]) (detail), 2000. One of five black and white photographs; parts 1–4: 37 × 27 1⁄2 inches each, framed; part 5: 37 × 32 inches, framed. Courtesy Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. © Estate of Mike Kelley. All rights reserved.

Howard Singerman is the Phyllis and Josef Caroff Professor of Fine Arts and Department Chair at Hunter College, a division of City University of New York. He is the author of Art Subjects: Making Artists in the American University (1999), and Art History, After Sherrie Levine (2011).