Martha Rosler, Nature Girls (Jumping Janes), from the series Body Beautiful or Body Knows No Pain, 1966–72. Photomontage. Variable size. Courtesy of the artist.

Any discourse which fails to take account of the problem of sexual difference in its own enunciation and address will be, within a patriarchal order, precisely indifferent, a reflection of male domination.

Stephen Heath, 19781

In 1983 Craig Owens revisited his influential pair of essays The Allegorical Impulse to address what he identified as an omission from his theory on postmodern tendencies in art. Characterizing his own analysis as a “case of gross critical negligence,” Owens admits: “I had overlooked something–something that is so obvious, so ‘natural’ that it may at the time have seemed unworthy of comment.” This “natural” and therefore invisible category was, of course, sexual difference. What Owens did in 1983 was to “indicate a blind spot in our discussions of postmodernism in general: our failure to address the issue of sexual difference–not only in the objects we discuss, but in our own enunciation as well.”2

At the crux of the Modern and Postmodern, second-wave feminism fought to foreground the issue of sexual difference as one of the most important concerns in society and art. Feminist artists and theorists of the late ’60s and early ’70s propelled a slow and profound paradigm shift that is only now being fully acknowledged by mainstream art institutions for the magnitude of its impact on art. WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution, the first major exhibition to examine the international foundations of feminist art from 1965 to 1980, fires the starting gun on the process of canonizing this expansive and diverse movement, providing institutional recognition of what feminist art proposed so long ago. And the influence of this exhibition is already unfolding; since Los Angeles’ Museum of Contemporary Art began publicizing this exhibition, we have seen a rapidly growing interest in feminist art spread internationally.

“My ambition for WACK!,” curator Cornelia Butler states in the exhibition catalogue, “is to make the case that feminism’s impact on art of the 1970s constitutes the most influential international ‘movement’ of any during the postwar period…” Reconciling a host of positions within feminism, Butler relies on Peggy Phelan’s definition that feminism is “the conviction that gender has been, and continues to be, a fundamental category for the organization of culture.”3 The centrality of gender in the understanding of how meaning is made in the world has infiltrated every outlook on art and life since the 1960s, but the major art institutions have largely ignored the significance and impact of this movement.

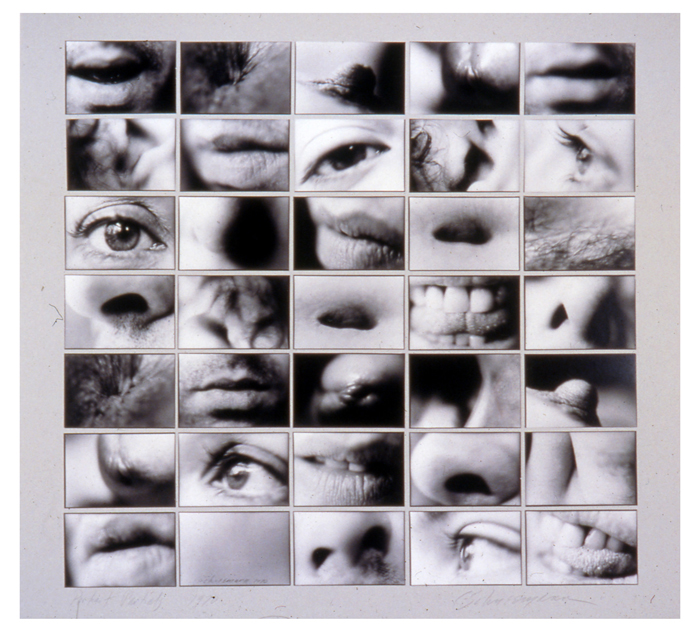

Carolee Schneemann, Portrait Partials, 1970. Thirty five gelatin silver prints, overall 26 7/8 x 26 in. Acquired through generosity of the Peter Norton Family Foundation. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, U.S.A.

Previous exhibitions by M. Catherine de Zegher, Nina Felshin, Susan Stoops, Marcia Tucker, Lynn Zelevansky, and Amelia Jones, as well as the book The Power of Feminist Art: The American Movement of the 1970s, History and Impact, edited by Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard, are cited by Butler as her major influences. Although these earlier projects signaled the urgency to re-route the course art history has taken, we have finally arrived at the moment when the combined influence of the exhibitions and scholarship on feminism can no longer be ignored. Showcasing a vast inventory of artwork for re-examination, WACK! marks the institutional acknowledgment of the extent and depth of the feminist transformation of culture.

One might argue, as Doug Harvey does in the LA Weekly, that because feminism is such a vast and all-encompassing category, “WACK! reinforces its monolithic invisibility.”4 But the exhibition doesn’t propose a change of terms along a traditional line of argumentation, where an antithesis is clearly argued in opposition to a defined point of view and thus effects a change. Rather, it showcases a movement that provided a cross-section of every creative, analytic, and historical method, and points out how the parameters by which we have measured our existence were lacking a major component.

Sensual, intellectual, and sexual, the quality of the artwork refutes the prevailing notions of “bad” feminist art. In another feat of intellectual curation that has become the signature of MOCA, the bold and powerful display overwhelms the audience with the formal, discursive, and historical impact of this vast body of work. Perhaps I am blinded by the fact that I have been waiting to see this exhibition my entire adult life. (Or is it a submissive gratefulness to being finally handed that which I have deserved all these years?!) It is not as if this exhibition lacks faults or omissions, but given its scope, ambition, and the gap in art history it aims to fill, to embark on a fault-finding fest would be easier than criticizing the Whitney Biennial. At this historic moment–the mainstreaming of feminist art–it seems much more interesting to frame what the exhibition is doing, instead of what it does not.

One of the strengths of WACK! is that it juxtaposes an impressive group of works–national and international–that have barely been exhibited, with foundational works that are already recognized as masterpieces. On a floor flooded with powerful artwork, WACK! foregrounds feminism not as an inventory of marginal practices, but as a series of contributions that stated their claim in relation to a mainstream. In the consolidation of this massive movement, it becomes clear how many of the artists have simply not been acknowledged sufficiently. Some of the artists showcased made artworks far more sophisticated and complex than male artists of their time. While the contributions of major male artists in Minimalism, Conceptualism and Pop remained within the comfort zones of the dominant discourse, WACK! reminds us that feminist practices that have come to be considered as staples of contemporary art were met by a host of resistances when they initially introduced the discourses of gender, or race, into art’s dominant discourses.

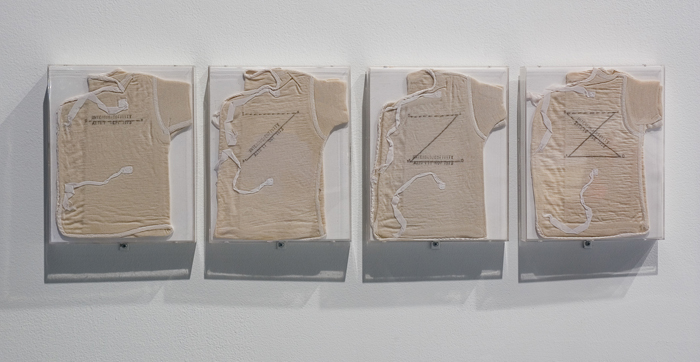

Installation view of WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, 2007. (Detail of Mary Kelly, Post-Partum Document, 1976.) Courtesy The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest.

When Mary Kelly’s Post-Partum Document was originally exhibited in London in 1976, only a few could fathom that the stains left on an infant’s diaper could be recoded as artistic mark-making, or that a psychoanalytic analysis of the intersubjective relation of mother and infant could drive such a significant contribution to conceptual art. Gradually, the historical implication of an epic like Post-Partum Document was acknowledged, and it is absolutely great to see it now–flesh, blood and excrement–where one can walk along this staccato of the mundane and read the subtleties of the day-to-day in a child’s initiation into the language of the self. Also on view are Kelly’s collaborations with Margaret Harrison and Kay Hunt on their project documentation Woman and Work: A Document on the Division of Labour in Industry (1973-75), showing a range of practices that intersected the theoretical, the social and the political with art.

In the early 1970s, Adrian Piper’s conceptual art flew into viewers’ faces, or over their heads. Interrogating identity at the intersection of class, race and gender, Piper fragments perceived notions about appearance and identity or the articulation of individual identity within language. Piper’s work converses with its audience in fearless textual confidence, confronting the racism the art world would prefer to ignore. Using conceptual art strategies, the aesthetics of Concrete Infinity Documentation Piece (1970) nevertheless echo a vulnerability of the body, risking the integrity of a personal sense of self by analyzing its foundation. In a lean grid of black frames, Piper collages her photographic, mirrored self-portraits onto graph paper, where they are accompanied by dense, handwritten diary entries charting her bodily activities over the course of a month. Working on the axis of paradoxical propositions, Piper speaks in what Benjamin Buchloh called “the aesthetics of administration,”5 yet she undermines the authority of the conceptual tone by forcefully interjecting subjectivity. The analysis of subjectivity is both a means for self-criticism (Piper is an accomplished Kantian philosopher) and a strategy for a politics of identity. “

Pimping, in the nude and in drag, Lynda Benglis’ notorious ArtForum ads inserted the gendered body as key to the interaction with minimalist sculpture. In a historical moment that relocated meaning from the artist into the space of the viewer, Benglis provoked a reconsideration of this critical paradigm in terms of gender identity. When the artist presented her own sexualized body in these outrageous ads, presented here in display cases, she shifted the focus onto gender, and the field could never again function as “neutral,” or employ the term as euphemism for white-male. Benglis’ work persistently disrupted the philosophical underpinnings of major art movements. Odalisque (Hey Hey Frankenthaler)(1969), drawing on both American Abstraction and Minimalism, is a composition of poured pigmented latex, its colors flowing into each other like magma, rendering gravity in fluorescent colors, while air-bubble craters dot it like geological phenomena. Neither painting nor sculpture, or contradictorily both, the work interrogated the metaphysical crux of presence around which distinctions between the transcendental spectator of abstraction and the embodied viewer of Minimalism were made. You were looking at a painting that was lying on the floor, like sculpture. The fallen painting (Fallen Painting [1968] is the title of a similar work by Benglis not exhibited in this show), recalled the psychoanalytic interpretation of women’s anxiety as fear of becoming a “fallen woman.” A minimal sculpture as painting, or an abstract painting as sculpture, the work lacked a fixed identity. In effect, the work declared that the stakes of art had changed. At the dawn of the postmodern in art, Linda Benglis shifted the terms of discussion by bleeding the distinctions between philosophical positions and by gendering the discourse. Philosophy, as a companion to art, needed to be revisited, and the discussion shifted from existential questions about being to social questions about identity and gender.

Installation view of WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, 2007. Courtesy The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest.

The significance of WACK!’s contribution to art history seems enormous, despite the fact that, as the process of canonization inevitably does, it cleans up some of the sticky, messy and disturbing aspects of feminism that made the movement indigestible for the faint of heart. Displaying this work in a white-cube setting, thirty years later, the blood, sweat and tears that were a part of its inception have been dehydrated or cured. (Despite video documentation and lectures by living artists, I can barely imagine what the experience of Womanhouse or the performances of Suzanne Lacy and Leslie Labowitz might have felt like.)

Back in the 1960s, the merging of second-wave feminism and art enabled artists to express, think, expose and create art of subject matter, media and attitude that made everyone uncomfortable. Feminist art broke skin and aired dirty laundry that belonged under our clothes or inside the body, behind the door, under the table–contained. Confrontational, difficult, emotional and sentimental, feminist art–from the psychological to the psychoanalytic, from the expressive to the conceptual–persisted in outing itself and its surroundings by foregrounding the oppressed, suppressed, and repressed.

WACK! brings together a multitude of works of diverse complexities, yielding unruly combinations of unexpected sensibilities. These are not your darling Dadaesque shock-tactics that we are witnessing here, as those scandals of yesteryear turned overnight into salon decor. In Linda M. Montano’s video, Mitchell’s Death (1978), the artist mourns the death of her ex-husband. An extreme close-up shot frames her face, which, pricked by multiple acupuncture needles, looks like a precursor to Hellraiser. Her monotonous chanting/singing of her remembrances is both painful to watch and meditatively cathartic. Yoko Ono’s Fly (1970) is a mesmerizing, close-up meditation on flies resting upon fragments of a female body. This contrast of species is scored by Ono’s haunting vocals, an extraordinary sound sequence that flutters back and forth between sounding human and sounding like an insect. Faced with the realities of limited working space in her tiny apartment in Poland, Magdalena Abakanowicz nevertheless resolved to make monumental sculpture. Working craft into the scale of architectural space, she wove natural fibers into structural environments mnemonic of orifices. Abakan Red (1969) (its title derived from the artist’s name) greets the viewer in the exhibition’s entrance with its peculiar hybrid of human and monumental scales.

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Abakan Red, 1969. Sisal and mixed media. Each: 157 x 157 x 137 13/16 in. Courtesy of the National Museum in Wroclaw. Photo courtesy of Magdalena Abakanowicz

WACK!’s contribution to art history is made by opening up, rather than attempting to fix, possible categories and classifications of feminism. Instead of wall labels, viewers refer to the gallery guide, which divides the space into loose themes, explaining the installation’s logic in a suggestive rather than an authoritative voice. The themes–Goddess, Gender Performance, Pattern and Assemblage, Body Trauma, Taped and Measured, Autobiography, Making Art History, Speaking in Public, Silence and Noise, Female Sensibility, Abstraction, Gendered Space, Collective Impulse, Social Sculpture, Knowledge as Power, Body as Medium, Family Stories and Labor–operate in multiple paradigms, flowing in and out of given scholarly taxonomies, proliferating the inter-textual dialogue between the artworks. Mixing and matching some of the old categories with new ones, and paying attention to artistic intention as well as posthumous critical interpretations, the exhibition is more a showcase of possibilities than a strict academic argument. Gone are the divisions between expressive and conceptual models; absent is the notion that subjectivity is inherently regressive; missing is the classification of an essentialist 1970s contrasted with a theoretical 1980s; nowhere to be found are the misconceptions of an anti-formal feminism or a lack of feminist painting.

Indeed, I was delighted to see so much excellent painting, from an era in which its detractors where plenty. Nasreen Muhamedi’s quiet investigations of the grid, in drawing and in photography, touch upon the infinite vocabulary of investigating the minimal. To combat the many arguments against the patriarchal legacy of painting or the obsolescence of representation, feminist painters introduced new dimensions to the practice. Joan Semmel’s headless lovers, in and after copulation, radiate with a sense of the human skin. The rendered figures retain a tangible sense of flesh despite the arresting artificiality of the colors. With a vantage point that reveals the erotic from a woman’s perspective, these sizable paintings are anti-idealized, delighting in the vulgarity of sex. Alice Neel’s intense foreshortening and confident use of color highlight the personality of her sitters, returning to portraiture with a 20th century freedom. Her stunning 1970 portrait of Andy Warhol after being shot by Valerie Solanas converses with Solanas’s SCUM Manifesto (1968) displayed in a case nearby.

From Solanas’s Manifesto to Tee Corinne’s Cunt Coloring Book, a multitude of publications, ephemera and artworks are organized in museum cases throughout the exhibition. These materials not only provide an invaluable resource for future scholarship and curatorial projects, but provide evidence of the social interactions, the collaborative atmosphere, the talking, performing, gathering, supporting, living, learning, theorizing, and debating that were the bustle of the feminist world. Video, though hindered (as usual) by problems of display, is a strong component of the show, both as documentation and as media in and of itself.

Installation view of WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, 2007. Courtesy The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest.

The installation as a whole provides ample space for the artworks to breath and dialogue, finding affinities across international boundaries and articulated alliances. Better late than never, MOCA presents us with the opportunity to mine the gamut of feminist artistic strategies, not in order to reuse them, but to further examine their analytic methods and to rethink what is the task of art and art history in the present.

Lastly, on the subject of excavation, it is still shocking that much of this wealth of excellent art, till very recently, has gone largely ignored by the market and museum collections, demonstrating once again how narrow-minded art buying can be. Wouldn’t viewing a work by Matthew Barney (an artist heavily influenced by feminist art) be worth so much more in a museum collection that also includes the referents of his performance-based work? One could find the foundation of his imagery through the Rose English equestrian exhibition events, Adrian Piper’s Catalysis and Carolee Schneemann’s performances.

Better late than never, it seems that in the last two years feminist art has suddenly been selling. There is still time for museums to compensate for years of neglect, beat the collectors to the artists’ basements, and get the artwork into institutions so that the vast creative output of this crucial historical period can finally be preserved and made available to future generations.

Nizan Shaked is a curator and an Assistant Professor of Museum Studies and Art History at California State University, Long Beach.