A landmark study commissioned by the National Endowment for the Arts in 2000 signaled an impending crisis for cultural institutions. The report, titled “Age and Arts Participation, 1982-1997,” cautioned that long-held assumptions about the baby boom generation (born between 1946-1965 and making up the largest percentage of the US population) had been overly optimistic. Boomers were expected to “age” into cultural participation, with the greatest surge coming from those in their fifties who theoretically possess the leisure time, money, and philosophical inclinations to become more involved in the arts. However, despite the educational and financial advantages of many older boomers, their involvement has been markedly less than had been anticipated.1 Younger boomers are apparently not picking up the slack either; in fact, their attendance at art events has actually fallen over time.2 When the NEA report was first released, it must have kept arts administrators awake late into the night as they pondered who would introduce younger generations to the arts—if not their parents and grandparents.

In an attempt to stem the attrition, some fine arts organizations have begun to dabble in what has become known as “experience design.” The strategies of experience design have been kicked around since the 1955 opening of Disneyland, when it was determined that consumers were willing to pay as much for services as they had for goods, provided they were given a satisfactorily entertaining experience. During the 1990s, enterprising marketing consultants began to push experience design beyond the boundaries of the theme park and into the mall at places such as the Universal Citywalk. Working with architects and designers, they melded data from the social sciences (psychology, ethnography, and sociology) and the humanities (history and folklore) with theatrics to devise lucrative retail environments where “memorable events” were for sale.3 Our society has become enthralled with the spectacle provided by these hybrids of commercial and public space. The popular Sunset Strip restaurant/nightclub, House of Blues®), exemplifies this new species of experience-oriented franchise, where soul food served during the Sunday “Gospel Brunch” is a prop in what has been termed by its proprietors as “eatertainment.”4

Far, far, subtler manifestations of experience design can be witnessed at numerous art museums across Southern California. The Orange County Museum of Art, having struggled in its recent past both with identity and finances, is the latest to sample its tenets. Under the energized leadership of current director Dennis Szakacs (formerly of the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York), OCMA just completed a $1.65 million renovation of its Newport Beach site. An additional $200,000 went into the Orange Lounge, a storefront satellite gallery nestled beside a Paul Frank boutique in the lavish South Coast Plaza mega-mall.

With the renovation, social space has become the centerpiece of the Orange County Museum of Art. The lion’s share of the remodel took place in the 5,000 square foot entry pavilion and outdoor sculpture court, not in the galleries. In the most noteworthy improvement, Bauer and Wiley Architects replaced a wall of windows with a series of large, rolling glass doors to cultivate the “seamless inside/outside flow” between the two public spaces, thereby expanding the museum’s capacity to entertain anticipated crowds for events such as film screenings, membership galas, and, perhaps most importantly, the Orange Crush (an evening series of DJ dance parties and concerts with a no-host bar). Complementing the enlarged public area is a stylish reception counter and a café called Citrus, a chic Patina spin-off where patrons can dine or chat over a glass of wine.

In a recent interview, Szakacs stated that the goal of the renovation was to create a “more memorable, exciting experience” for patrons. He went on to express a hope that the museum improvements would provide OCMA with the ability to “entertain someone for an entire day.”5 Szakacs has a great deal of entertaining ahead of him, as he intends to double the museum’s 3,000-person membership in the next year and a half.6

The 2004 California Biennial was selected to inaugurate the newly reopened space. With this admirable choice, OCMA signaled its intention to re-establish itself as a strong advocate for California artists. The whole museum was devoted to the exhibition, a first in the 20 years that OCMA has hosted the Biennial. According to Chief Curator Elizabeth Armstrong, this gesture was in recognition of California’s growing role as an international center for artistic activity.

A still photograph of Joel Tauber’s Searching for the Impossible: The Flying Project (2002- 03) supplied the leitmotif for the Biennial exhibition. Ian Lipsky’s image of Tauber floating across a bright blue sky, buoyed by comically-sized white balloons and (ostensibly) the wind in his bagpipes, appeared in nearly all OCMA press materials. It handily evinced everything that is foolhardy, obsessive, and joyful about artistic practice.

New media artists made a particularly strong showing. Calling her Landslide (2004) a synthesis of the “code and the territory,” Shirley Shor’s real-time software animation was mesmerizing. Marco Brambilla’s three-channel video, Half-Life, from 2002, was even more chilling today because it was easy to imagine the same young, multi-ethnic virtual warriors conducting actual door-to-door searches in Fallujah. At the other end of the museum was Kerry Tribe’s quietly existentialist dualscreen projection, Here and Elsewhere (2002). Sadly for Tribe, her video was installed near Mads Lynnerup’s Rock Band Project: Newport Beach (2004), a live garage band rehearsing in deafening fits and starts.

Marco Brambilla, HalfLife, 2002. Three-channel DVD (ed. 5), Dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and Christopher Grimes Gallery, Santa Monica

Sculptural works also provided highpoints for viewers. Glenn Kaino’s grandly gonzo mechanical wonder, Simple System for Dimensional Transformation (2003) was undoubtedly a big hit with children. Mindy Shapero’s freeform Burnt Rainbow and Take Your Eyes Out to Sea (both 2004) both reveled in their idiosyncratic materiality. In Pennants (2004), Mark Dutcher wryly undermined his lamentation for a deceased lover by calling attention to the sentimentality of his gesture. His pennants, made with paper and wax, looked similar to the kind that brings cheap gaiety to dismal places like used car lots. With them, he seemed to suggest memorials could be the sorriest of affectations, revealing far more about the living than the dead.

Glenn Kaino, Simple System for Dimensional Transformation, 2003. Mixed Media, Dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and The Project, Los Angeles and New York

Throughout the exhibition, Dennis Szakacs and his curators appeared to succumb to the marketing principle of more is more. Frequently touted was the fact that 120 artworks had been brought together for the Biennial. This superstore-like presentation philosophy was not, however, advantageous for several artists, whose work would have benefited from increased rigor during the selection process. Furthermore, numerous pieces were crowded into the glamorous entry pavilion, because Szakacs insisted that art be the very first thing patrons saw when they entered the facility. His decision to allow artwork to compete with capital improvements led to some unintended consequences, probably not the least of which was the time spent by staff cautioning museumgoers not to sit on Sean Duffy’s twinned Double-Wide Sofas (both 2001).

Installation view, 2004 California Biennial. Mark Dutcher, Pennants, 2004. Mixed Media, dimensions variable. Courtesy of SolwayJones, Los Angeles. Mindy Shapero, Burnt Rainbow, 2004. Steel, wood, acrylic, 92” x 60” x 60”. Courtesy of the artist and Anna Helwing Gallery, Los Angeles.

The ValDes (San Fernando Valley Institute of Design) installation also blended too closely with the surroundings. Apropos of the Orange County setting, co-founders Peter Zellner and Jeffrey Inaba presented a multimedia analysis of “post-suburbia,” the market-driven and master-planned tracts that have taken root far away from urban centers. They included an intriguing examination of Orange County, China—a housing development one hour from Beijing that replicates the quintessentially post-suburban community of Irvine. Because, however, the ValDes display was tucked alongside the mod new dining area, their corporatelooking vinyl banners and didactic materials looked ever so much like an infotisement from the Chamber of Commerce.

Ruben Ochoa’s artist residency project, Class: C, suffered from an identity crisis in the open space as well. Since 2001, when Ochoa transformed a commercial van from his family’s tortilla business into a mobile art gallery, he has staged interventions at art establishments and delivered exhibits to new audiences in working class neighborhoods across the Southland. For the run of the Biennial, Ochoa scheduled fourteen stops around Los Angeles and Orange County, during which he presented artwork by Sandra de la Loza, the Pillow Lavas collective, and collaborative team of Aya Seko and Christopher Ferreria. Back at OCMA, a modified video arcade console and an object-filled plywood cabinet stood in for the street performances. In a region as notoriously divided along lines of race and class as Orange County, Ochoa’s proxies for his confrontation about “ownership” of high culture should have hummed with a potent charge. Instead, they seemed mute, awkwardly plopped as they were near the museum entrance and gift shop. Bereft of adequate signage, their interpretation was left entirely up to passersby, who must have momentarily wondered what to make of the funky stuff as they exited the building.

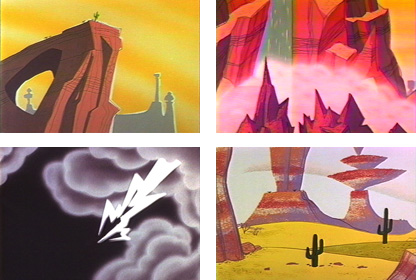

More bizarre was the installation of Mungo Thomson’s fantastic animation, The American Desert (For Chuck Jones) (2002), on a plasma screen monitor behind the café bar. When asked who allowed this piece to fully cross over into consumer turf (situated where one might expect to catch the current score in an Anaheim Angels baseball game), the curatorial staff acknowledged that it was their idea. Certainly, other Southern California art institutions have merged the art experience with merchandising (look no further than LACMA, which has for years force-funneled herds of blockbuster attendees through tchotchke-laden gift kiosks). Nevertheless, by not clearly signaling to the public which is which, OCMA has set a very disconcerting precedent.

Mungo Thomson, The American Desert (for Chuck Jones), 2002

Video, 34 min. Collection of the Orange County Museum of Art;

Museum purchase with funds provided through prior gift of

Lois Outerbridge

Biennial offerings did not fare better at the Orange Lounge, the highly touted site developed by OCMA to introduce young audiences to digital, video, and sound projects. A preponderance of the construction money was obviously spent tricking out the place to look hip. Unfortunately, the design team seemed to have lost track of the important acoustical needs for new media in the one place where it should have been given full consideration. The Black Box Gallery was not adequately insulated, hence noise from Kota Ezawa’s digital animation, Who’s Afraid of Black, White, and Grey (2003) rudely intruded into funny moments offered by Thomson’s sound piece, The Collected Live Recordings of Bob Dylan 1963-1995 (1999), playing in the front room. Gimcrack headphones did little to shield Dylan from the constant bickering of Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor.

The Great Park Project (2004), a virtual piece by Amy Franceschini of the new media collective Futurefarmers, also languished at the Orange Lounge. In order for this piece to succeed, Franceschini needed to inspire active participation from her audience about the upcoming conversion of the defunct El Toro Marine Corps Air Station into a community greenbelt at the heart of Orange County. A month after her website was unveiled, Franceschini had received only a few artist project proposals and a paltry number of responses to an online survey that was supposed to collect extensive commentary and suggestions from OC residents about the mission of this highly contested public space. For those viewers who could not fathom the too-slick Macromedia Flash web interface employed by OCMA, this ambitious eco-art project was rendered essentially inaccessible. A bit of active direction from on-site staff perhaps would have helped to ameliorate the problem.

In a way, there was both too much and not enough integration of artwork from 2004 California Biennial into the new experienceoriented setting. In a perfectly designed environment, every function is telegraphed to users, so that they unfailingly know what to do and where to place their attention. This aspect of design is crucial in circumstances when the message is unfamiliar. Otherwise, users dismiss the perceived dissonant elements as irrelevant. At OCMA, while less art-savvy art patrons would have had little trouble differentiating paintings and sculpture from the environs of the entry pavilion, conceptual projects that operated outside the parameters of traditional art posed more of a challenge. Had the exhibition staff more effectively offset the artwork from its fashionable surroundings, viewers would have a greater opportunity to identify what they were looking at as art and, consequently, give it closer attention.

If designing an entertaining environment is what is takes to get people in the door, then it is inevitable that museums will embrace this strategy for survival. However, there are many kinds of experiences a viewer can have in a museum, from the marvelous to the contemplative or edifying. Not all would be improved by a cocktail, club soundtrack, or crowd of single people. Art administrators would be well advised not to take to heart everything that marketing consultants whisper in their ears. Because while good design is about tying up loose ends, much of the very best art unravels the ends even further, in ways often as unassuming as they are unexpected.

Kristina Newhouse is curator of the Joslyn Fine Arts Gallery in the City of Torrance.