Upon entering Ends of the Earth: Land Art to 1974, the sprawling survey at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, visitors encounter a large video projection of the artist Jean Tinguely gathering junk in the Nevada desert, assembling it into a kinetic tableau of whirring, smoking wreckage, and then exploding most of it from an electronic control panel a safe distance away. Study for an End of the World, No. 2 (1962) was originally broadcast on NBC. The scripted finale of the broadcast is a hilarious anticlimax—“the end” is fraught with malfunction, more whimper than bang.

Next to the large video projection are a handful of small drawings, easy to miss but essential to the Surrealist character of Tinguely’s project. The doodles and jottings on one framed typing-paper drawing spell it out: “un revée” (a dream). The drawings reveal that the project was initially conceived in a primarily pictorial space. Tinguely seized upon the American West as a morphological counterpart to the evacuated backdrops of classic Surrealist painting. It is the space of Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, and Yves Tanguy, the flat horizon with blended gradients of color that suggest a curiously flattened depth, but this time transposed into the real space of the desert. Also in the Surrealist fashion, Tinguely also brought his entourage, and a press crew.

Or rather, the press crew brought him. NBC financed the entire production, sculpture included, for broadcast as “a documentary.” And thus, unsurprisingly, the project remains hostage to the editorial sensibilities of a corporate TV studio. It’s very accessible, and even mildly entertaining, but it doesn’t reward multiple viewings. Tinguely is a stupendous artist (the Tinguely museum in Basel is probably the best single-artist museum in Europe), but this video is not the proof.

The video is used to introduce the vexing question of Land art’s relationship to media proper. If Study for an End of the World isn’t a work of art exactly, it isn’t an ordinary television broadcast either. In this respect, Tinguely’s relationship to the NBC video is a departure from the abstractionist 1950s model of painting’s relationship to media. Jackson Pollock, for example, painted for the camera in his Life magazine profile, and for Namuth’s films, but his practice as a painter was easily materially separated from these photographs and films. Pollock played to the camera, to be sure, but Tinguely’s daffy showmanship, his specific choice of the site as a pictorial background, his sly humor (“No. 2”?) and his position as a commissioned artist mark an essentially different circumstance. The camera binds these differences: where Namuth’s photographs exist primarily to affirm the existential authenticity of Pollock’s canvases, Tinguely’s moving image of the desert as a real-life surrealist expanse exists primarily, perhaps exclusively, in the camera. The video doesn’t merely promote, represent, or relay “the work,” it contains it utterly. Historically and conceptually, this establishes the groundwork for much of what is to follow in the exhibition.

But wait a second, what makes this video “Land art”? “Earth art” has typically been thought of as, well, sculpture made of earth. In the scholarly catalog that accompanies the exhibition, Willoughby Sharp, curator of the 1969 exhibition Earth Art at Cornell University, recalls how his principal requirement for works submitted to that show was simply that dirt be somehow involved. So when the artist Walter De Maria proposed a sculpture consisting of a mattress and an audiotape of crickets, Sharp rejected it as out of bounds. Instead, De Maria arrived the night of the opening, neatly spread some dirt on the floor with a broom, and then scrawled “god” and “fuck” into the dirt with the broom’s butt end. With the college president wandering around the opening, the gallery staff went into a panic, and De Maria’s piece was quickly cordoned off, swept up and disposed of the next day. Sharp muses, “Why he did that, I don’t know. We’ve stayed friends, so I don’t think it was because his original piece was rejected. But I’m not sure.”1

The story is funny, but it also gets at something deeper, more difficult to articulate or acknowledge. It’s a telling moment, one in which the nihilism, ferment, paralysis, and uncertainty of the era come bubbling through. Here’s Robert Smithson, philosopher-king of the Land artists, in 1971: “Why do even the best-installed shows have the appearance of a dud? Why are the plain white walls of a modern museum as oppressive as the imperial halls of our older museums? Could it be that we spread culture not to liberate but to enchain?”2

MOCA’s show has none of the“appearance of a dud,” but it doesn’t exactly exude ferment. If it sometimes feels like homework, it might be because the generation that produced this work was keenly aware of art’s potential to be oppressive and was determined to interrogate those possibilities directly, in ways that might easily be misread at a distance. The forms are for the most part numbingly similar: Mounds of earth are dutifully shaped into tidy geometric piles, working plans are presented on signed and framed pieces of typing paper. This was the age of the diagram and the objectified splitting of the art act into proposal and execution. It’s not entirely clear whether some of the animating ironies and inside jokes of the period in question have simply been lost to time, or whether some of this work is just not as exciting as textbooks have led my generation to believe.

It’s not simply a question of art versus the documentation of art. In their essay that opens the catalog, the curators Philipp Kaiser and Miwon Kwon insist correctly, if somewhat defensively, that nearly everything in the exhibition was originally shown in a gallery as art. They are not, they make clear, “retroactively recasting past productions of ephemera or supplementary material into a new frame of elevated legitimacy.”3 Land art took a wide variety of forms in gallery settings, alongside the great permanent outdoor sculptures, of which there are in fact relatively few.

Remarkably, there’s never been an Earth art survey show in the United States until now. Over the past twenty years, MOCA has unpacked most of the various tendencies of the late sixties/early seventies moment, in a renowned program of survey shows. With the turn to Earth art, it is clear that the museum has saved one of the most difficult and institution-resistant of those tendencies for last. Viewed in this context, Ends of the Earth has a feeling of endgame about it. The collective, even collectivist, energy that animated shows like the feminist spectacular WACK! is nearly absent here. While Ends of the Earth adds lots of women to the Land art mix, the genre remains mostly an art of romantic loners, most of them men.

Why did so many artists all of a sudden begin working with dirt in the sixties? It’s not an easy question to answer, and the show doesn’t presume to offer a singular origin narrative. It had something to do with the perceived exhaustion of formalist painting and hard-edge sculpture, the critical anxieties surrounding Pop art, and the nascent interest in ecology and the environment.

For precedent, one might look, as so often happens, to the work of Robert Rauschenberg (which isn’t included in Ends of the Earth). Rauschenberg’s Dirt Painting (1953) consisted of dirt in a wooden frame and was covered with mold. Rauschenberg made a few variations on this theme. Supposedly, when he showed them at the Stable Gallery, he would visit them often to water them, keeping the mold alive. Unlike his gold leaf paintings from the same period, most of the dirt paintings haven’t survived.4 The dirt paintings are the double of Rauschenberg’s all-white paintings made just a couple years earlier. Their dialectic within the cosmos of early Rauschenberg is easily grasped: the perfectly clean implies the utterly dirty. The utterly dry implies the wet. A fixed geometric form implies the possibility of a mutating, growing, organic form, that of the mold. New York Minimalism and Land art were, from the beginning, two sides of the same coin.

Rauschenberg’s omission from the Earth art history is partly a genuine difference in sensibility. He is the golden retriever of twentieth-century art, buoyant almost to the point of irritation, and out of step with the mordant critical seriousness of most of the artists in this show. But Rauschenberg’s omission is also a product of timing: by the late sixties, the political landscape had changed. Political disaffection was going mainstream, and American art, Rauschenberg’s especially, had taken hold in Europe. It was strategically useful for champions of Earth art to see Rauschenberg as one of the Pop artists, “in the ‘service’ of consumerism,” in the words of curator Germano Celant.5 Celant explains the politics of the moment:

The colonizing arrival of American art [began] with the award [of the Golden Lion] to Robert Rauschenberg at the 1964 Venice Biennale and the consequent invasion of Pop art to which we were looking to respond while still evading French provincialism, which, from 1945 to 1960, was still dominant in Europe. For the generation that was beginning to work during the early 1960s on the precedents set by [Alberto] Burri and Lucio Fontana and linguistic departures made by [Piero] Manzoni, Enrico Castellani, Michelangelo Pistoletto, and Giulio Paolini, the intent was to form a collective identity that could set itself against both the old French hegemony and the recent American one. The need arose to form a “front” that would linearly unite Turin–Milan with Düsseldorf–Cologne, Amsterdam, and London.… Of course, we were aware that it wasn’t possible to establish a new force without the American artists present; it was just that they couldn’t already be members of a defined movement like Pop or Minimalism.6

For those looking to alternatives to Pop, for whatever reason, the Land artists played this strategic role capably. Ends of the Earth reconstructs this transatlantic art-world alliance with a mix of acknowledged masterworks, lesser-known works by brand-name artists, and total unknowns. The show is expansive, with 250 works by over 80 artists. It’s a fine model for a large survey show, one that allows for both familiarity and discovery.

In the acknowledged masterworks category are Charles and Rae Eames’s film A Rough Sketch for a Proposed Film Dealing with the Powers of Ten and the Relative Size of Things in the Universe (1968); Smithson’s film Spiral Jetty (1970); Michael Snow’s La Région Centrale (1971); and somewhat more modestly, Herbert Bayer’s Earth Mound (1955), an elegant, early, and influential piece, documented here by two black-and-white photographs. In the company of a blizzard of like-minded works from their era, the inspiration of these landmark pieces shines even brighter than usual. (More on Smithson in a bit.)

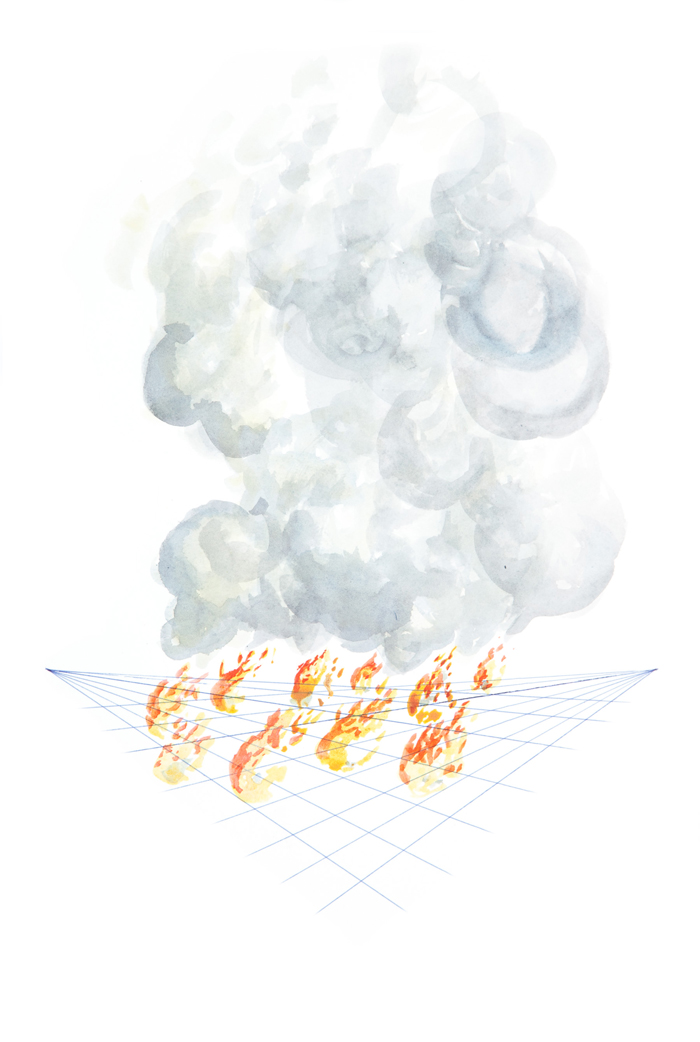

Lesser known works by well-known artists include Giovanni Anselmo’s Direzione (1967–68), a compass embedded in a large wedge-shaped piece of granite, pointing due north. Like almost all of his work, it’s clever without being glib. Joseph Beuys is represented by Loch-Rannoch (1970), a half hour black-and-white film of a Scottish moor, shot from the window of a slowly moving train. The film was originally used as the background of a performance. The footage is beautiful, but installed as it is here on a small monitor, in an odd point of passage, and with no gallery bench, it’s almost impossible to watch. Landscape for Fire (1972), a short color film by Anthony McCall, shows burning puddles of petroleum, carefully measured and placed across a disused World War II airfield, according to a gridded geometric score. It’s simple, brooding, and memorable. With its tropes of geometry, mapping, optical transmission, and the “slow burn,” it can be seen to lay the thematic groundwork for Line Describing a Cone (1973), McCall’s well-known projection piece that he would complete the following year.

Paul McCarthy contributes three “scores for actions” from 1968, before he moved to Los Angeles. These are pithy typewritten descriptions of simple actions using dirt, with titles like Competitive Digging and Digging a Trench across the Desert. They’re really just historical anecdotes, serving only to demonstrate that the earthwork genre was a rite of passage for almost every ambitious American artist who kept up with the magazines. Also in this category is Mary Kelly’s An Earthwork Performed (1970), which, in its installation at MOCA, feels like the half-articulated residue of a performance. It’s a pile of mineral coal with a shovel, a microphone, and a film projector that wasn’t running each time I visited. It’s strangely inert, lacking the formal panache and complex personal dimensions that characterize Kelly’s best work.

Then, there are scores of artworks by artists and artist groups that for many are not familiar. Their presence here is the result of exhaustive research. These include the Slovenian OHO group, Vancouver’s N.E. Thing Co, the Czech artist Zorka Saglova, the German artist Heinz Mack, and the Iceland artist Sigurdur Gudmundsson. The inclusion of this work is part of an explicitly revisionist program on the part of the curators and part of an attempt to point the way to a broader international understanding of the Land art category. But, to risk generalization (as a reviewer always must), with much of this work, you can’t help wondering if you just had to be there. This is partly because of some of the art’s emphatically performative character, which locates “the work” in a poetic foretime, of which the photograph or film is in some cases intended as a tragically pale reminder. But it’s also because the analogy between art and printed graphics, especially the magazine page, which was developed so aggressively in this period, allowed much of this work to operate convincingly outside the institution. Dragged back into the institution, some of these image and text works feel like yesterday’s papers, caught in the very obsolescence they were partly designed to question.

As everybody knows, MOCA’s great run of survey shows has coincided with the fluorescence of Los Angeles as an art production capital. But where the intertwined character of historical work and contemporary production was implicit in each of the earlier MOCA surveys, it is harder to discern the connections of Land art to the contemporary. There are a few points of contact: the Bay Area group Survival Research Laboratories carries on the tradition of Tinguely’s festivals of self-destructing machines, in an outrageous, comic-book vein. High Desert Test Sites, the biannual gathering in Joshua Tree, features sculptures and performance in remote desert locales. And the Center for Land Use Interpretation leads a strong series of public programs that extends the interest of the Land artists in the intersection of the natural and the built environment. But, generally speaking, people don’t make art like this anymore. Gone are the days, my friend, when you could garner serious attention by digging a trench and filling it back in again.7

The legacy of Earthworks and Land art lies in a more general license to operate (even if only temporarily) outside the confines of the gallery. In retrospect, it is obvious that this was not an exit from the gallery system, but an extraordinary expansion of its logic. Land art’s exertions at the art system’s limits were hypertrophic, ultimately strengthening and extending the reach and logic of that system.

The elephant in the room here, of course, is the absence of Walter De Maria and Michael Heizer. On the face of it, a Land art show without Heizer is like “Peanuts” without Charlie Brown. As laboriously documented in the catalog (but not in the show), in the late 1960s Heizer, De Maria, and Smithson were the ruling triumvirate of Earth art—collaborators, comrades, and compatriots. Virginia Dwan, the gallerist who mounted the exhibition Earthworks, in 1968, in Los Angeles, explains their absence thus:

I must commend the curators of “Ends of the Earth” for their bravery and ambition in the face of a tremendous challenge. But I must also espouse the sentiments of De Maria and Heizer that the photograph is not the work. Earthworks must be experienced as actual, palpable structures. It is my hope that short excursions to these very real works will become a part of the lives of many people. The sense of space and time and one’s place in the universe they bestow is inherent and intrinsic to each of them and to each of us.8

Huh? What’s intrinsic to what exactly? Dwan’s indirection here is forgivable—the point is that it’s authentically difficult to describe an aesthetic encounter with the hero-objects of Land art without falling into a hopelessly cosmic romanticism. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of art-tourist bloggers have attempted and failed. Earthworks promise escape from the system, escape from urbanism, perhaps even from capitalism itself. They dangle the critically unfashionable possibility of an unmediated encounter, a first-person, fully embodied experience, and they do it so well that even a megadose of history, theory, and criticism to the contrary may not fully erase the tremor of that promise.

The irony of Heizer’s nonparticipation is that he is actually fairly significant as a photographer. His Dissipate 2 (1967), a six-foot-tall backlit photographic transparency of a Nevada Earthwork shown in Dwan’s original Earthworks exhibition, was far ahead of its time; it was over a decade before Jeff Wall would hit upon a similar technique, to very different ends. Similarly, at the Whitney Museum’s painting annual in 1969, Heizer’s contribution was not a painting but a huge photograph of a dye painting in the desert, also decades ahead of its time.

Adding to the irony further still is the simultaneously staged but completely separate exhibition of Heizer photographs across town at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, timed to coincide with the unveiling of Levitated Mass (2012), a new outdoor sculpture by Heizer on the LACMA campus. At LACMA, contra Dwan, Heizer photographs stand in for artworks in the most emphatic fashion. Actual Size: Munich Rotary (1971), consists of one enormous, darkened gallery filled with towering large slide projections of an Earthwork produced in Germany. In another massive gallery, Actual Size (1970), is full of black-and-white snapshots of large rocks, printed enormously large on wall vinyl at, yes, actual size. Heizer’s halls of giant projections and mega-prints are, by every indication, earnest attempts at a re-creation of the visual space of the objects and environments they represent. But in spite of having been remade using contemporary equipment and materials, they seem to belong to an earlier, more trusting time. It’s an approach that, in Jean Baudrillard’s theory of the simulacrum, might be designated as “pre-modern,” in which the signifier (the photograph, in this case) is meant as an utterly faithful copy of the real item. In the gallery of vinyl prints, the result is a strangely dissonant combination of mow-’em-down advertising banner technology and rock-hound shutterbuggery, in a way that seems to uncomfortably exceed the artist’s own intentions, in the best, most productive sense. The zone of overlap between Heizer’s buckeye cowboy negativism and the pop gigantism of LACMA’s Broad building is a very thin vein, one that these prints are surprisingly able to locate and extend.

The Land artists deserve credit for wrestling deeply, if sometimes inconclusively, with the question of a photograph’s relationship to its subject. Heizer’s (and De Maria’s) late-career half-hearted disavowal of photography as a medium for their work is, of course, a reversal that they are entitled to make as creators, but it doesn’t settle the status of those images, which have a permanent life in books and on the Internet.

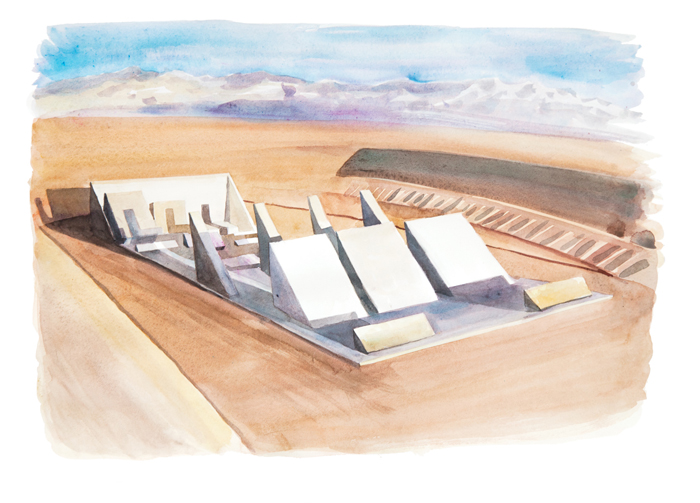

Since 1972, Heizer has spent most of his time on a remote ranch in Nevada, where he is completing City, possibly the largest sculpture ever made, a network of linked geometric structures made of concrete, steel, and earth. By all accounts, it’s a sculpture designed to last a few thousand years. It has been “several years from completion” for at least a couple of decades. Egotistical, paranoid cranks are everywhere in the history of art, but Heizer is a crank of a higher order, a complete singleton. It’s hard to think of another artist who has attracted institutional and financial support for his projects on such a massive scale while almost never appearing in public and vigorously attempting to quash the presentation of his work. In short, it’s hard not to be impressed.

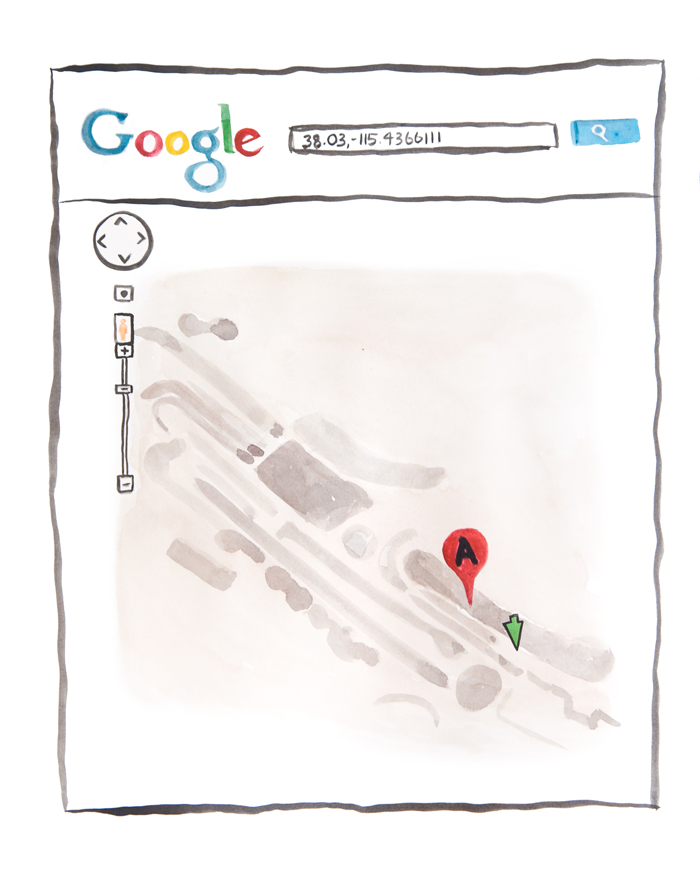

Despite Heizer’s best efforts to keep out interlopers with cyclone fencing, “no trespassing” signs, and threats of gun violence, City bubbled back up into public view a few years ago, courtesy of the creeping eyes of Google Maps.9 It’s a soft, somewhat vague image, a symphony of browns. The images appear to have been taken at high noon, so that no lateral shadows are visible that would precisely model the form. Still, it’s exactly what Heizer doesn’t want, what he calls a “gestalt” view, by which he means a sweeping everything-in-a-single frame panorama or overhead view. (Google’s orgy of information and connectivity also probably does a deeper violence to any vestigial fantasy of pioneer frontiersmanship that the Land artists seem to have nourished.)

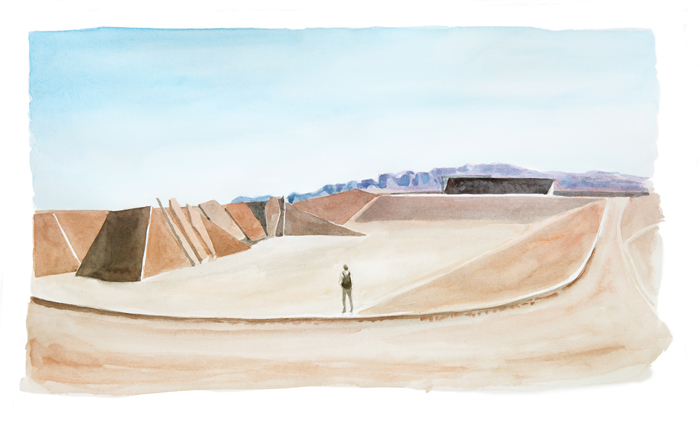

Indeed, the very form of Heizer’s City seems designed to elude the photographic, to exceed and evade its powers of capture. Like most, I haven’t seen it, but some features of the piece are known. Each of the sculpture’s distinct zones (“complexes” he calls them) is sunk below the horizon line, carved out of a massive negative space in the ground. The below-grade forms defy the visitor’s ability to gauge the overall scale of the piece from a distance. Reportedly, standing a few hundred yards back from the piece, the visitor sees only the mountains on the horizon. Another aspect of this layout is that when one descends to enter the sculpture, the mountains on the horizon disappear from view. “I’m not selling the view. You can’t even see the landscape unless you’re standing at the edge of the sculpture,” Heizer insisted in 2005, in his most recent public statement on the piece.10

Like many artistic undertakings, this aesthetic of the unphotographable began as a byproduct of other formal concerns. The notion of Earth art exceeding photographability through scale and position first appears in the literature not as a strategy, but as a problem. In a 1972 interview with Paul Cummings, De Maria explains his awareness of the difficulty:

De Maria: For instance I did this piece on which there has been no article yet but it’s a piece of about three miles of lines cut into the desert in a certain configuration and it takes you about four hours to walk through this sculpture.… It’s a 100 miles northeast of Las Vegas; I’ll draw you a map, sort of back roads out there in some hidden valley.… But anyway, it takes you about 2 or 3 hours to drive out to the valley and there is nothing in this valley except a cattle corral somewhere in the back of the valley.… Now, I did this piece in 1969 and I haven’t done an article on it because I didn’t find a way to photograph it properly. You can only photograph in multiple views, you know, like this is looking east and this is looking…

Cummings: A satellite shot.De Maria: Well, that’s true, but that’s a different experience because that’s an experience like a drawing but this is an experience at ground level, it’s a different experience.11

De Maria’s comment is not a full-fledged theory of photography, but it manifests a significant problem at photography’s perimeter: how to consider situations in which sheer (absolute) size conflicts with photography’s ability to communicate (relative) scale. The totalizing overhead view of a satellite is similar to drawing in the sense of the map-making tradition, but opposed to drawing in that it nullifies traditional perspective, supplying instead an infinitely extensible, gridded space. Heizer and De Maria would both go on to make a virtue of this difficulty, using enormous size as a way of going beyond scale, to create environments that frustrate ordinary habits of visual comparison, sites that are not entirely framable using photographic media, except possibly as an extended photo essay or film. De Maria isn’t above enforcing this point of view: beginning early on, visitors to The Lightning Field (1977) have been barred from bringing cameras. The goal is not to stifle reproduction, per se, because a set of premade 35 mm slides (today, postcards) could be purchased from a kiosk, but to ensure that the act of photography didn’t preemptively define the visitor’s visual experience. In practical terms, this is probably a futile fight: in the end, the photograph always wins.

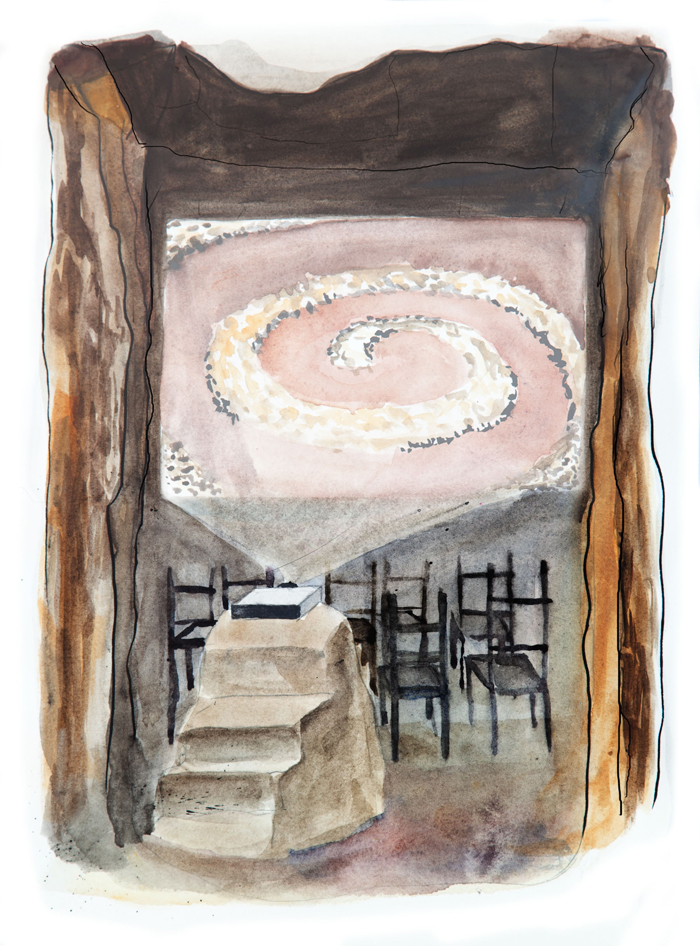

And so it is that in the MOCA show, Smithson’s film Spiral Jetty roundly dominates, as the piece that most fully develops the poetics of the relationship between Earth art and media. In Smithson’s 2004 MOCA retrospective, it was relegated to the basement screening room, with the misleading suggestion that it was some sort of documentary. Here is it again, this time properly installed on the main floor as a major work, perhaps the major work of its genre.

At the core of Smithson’s project was a strategy to subvert the hierarchical categories of “primary” sculpture and “secondary” reproduction. This began as a kind of elaborate joke. Writing about some of Smithson’s published writings, Mel Bochner remembers Smithson’s process this way:

We all started speculating that if slides were all anyone wanted to see, and if they were already a form of reproduction, was there any need to make actual works? In other words, why bother with production when you could go straight to reproduction? And wouldn’t this go a long way toward subverting the marketing system that held artists in its iron grip? But the question remained: What to actually do? This is where the literary hoax, a form perfected by Borges, came into our conversation. Why not camouflage the work as a magazine article, then surreptitiously slip it into the media stream? Without there ever having been an original, the reproduction would become the work of art.… We would completely bypass the galleries, transforming a secondary source into a primary medium.12

The analogy to the Spiral Jetty film’s production is nearly exact. The piece is a filmic commentary on the modes, methods, and ideals of sculpture, one that deliberately operates quite outside sculpture’s specific physical boundaries. As in Tinguely’s video produced by NBC (which Smithson hadn’t seen), the sculpture exists through the film. In his direct engagement with the various conventions and tools of film,13 however, Smithson’s production is the more auteur. As a filmmaker, Smithson was deeply alert to the parallel world of experience that photography purveys: “The disjunction operating between reality and film drives one into a sense of cosmic rupture,” he wrote in his essay on Spiral Jetty. The generically upbeat overdubbed corporate voiceover in the NBC film of Tinguely’s performance is the perfect cultural foil to Smithson’s stoner mumble, which drawls a repetitive list of compass points and geologic features. It’s a hilarious montage of serious science and stoner poetry—ratiocinative recitative and bright purple prose. Spiral Jetty thrives on the depth of its own contradictions, and in this exhibition one sees the exact locus at which Smithson exceeded most of his contemporaries.

* * *

I visited the site of Spiral Jetty once, almost a decade ago. I wish I could say I was a fan at the time, but the truth is that an old friend wanted to meet up, suggested the spot, and it seemed like a good excuse to fly out of town, rent a truck, and tool around. Arriving at Rozel Point in the very early morning, we experienced something like Smithson’s “cosmic rupture” in reverse, a falling to Earth that was simply mundane. The site, or what’s left of it, seems absurdly small, much smaller that the film suggests. We felt certain for quite a while that we were at the wrong place, perhaps a reduced scale model for Spiral Jetty made by some interloper. It’s also very close to another manmade structure, an “oil jetty” that was apparently there when the film was shot, although the film never shows it, and it’s very hard to understand how it could possibly have been cropped out given the framing of some of the wider shots. I’ve found it difficult over the years to communicate this to people who haven’t trundled out to the site themselves. When you experience something quite differently from how it looks in a photograph, and recount it later to others, they will universally assume that you’re simply misremembering or confused. Such is the authority of the medium.

My friend and I stand on the shore of Great Salt Lake, trying to discern whether or not we have in fact arrived at our destination. The density of the mineral deposits in the water, blown by an intense warm wind, produces great volumes of a strange pink foam at the edge of the lake. Bundles of this foam break free from the water and tumble across the dry land. My friend films these flights of the tumble-foam with her super-8 camera, chasing them doggedly across the landscape. The foam turns out to be our destination: more puffy pink than blood red, shapeshifting and amorphous, impossible to pin down, laugh-out-loud funny, and mostly comprised of hot air.

Benjamin Lord is an artist based in Los Angeles.

Melissa Huddleston is an artist currently based in Los Angeles. Her drawings for this article are interpretative illustrations based on the work of Jean Tinguely, Herbert Bayer, Anthony McCall, Michael Heizer, Walter de Maria and Robert Smithson, and the lore that surrounds them.