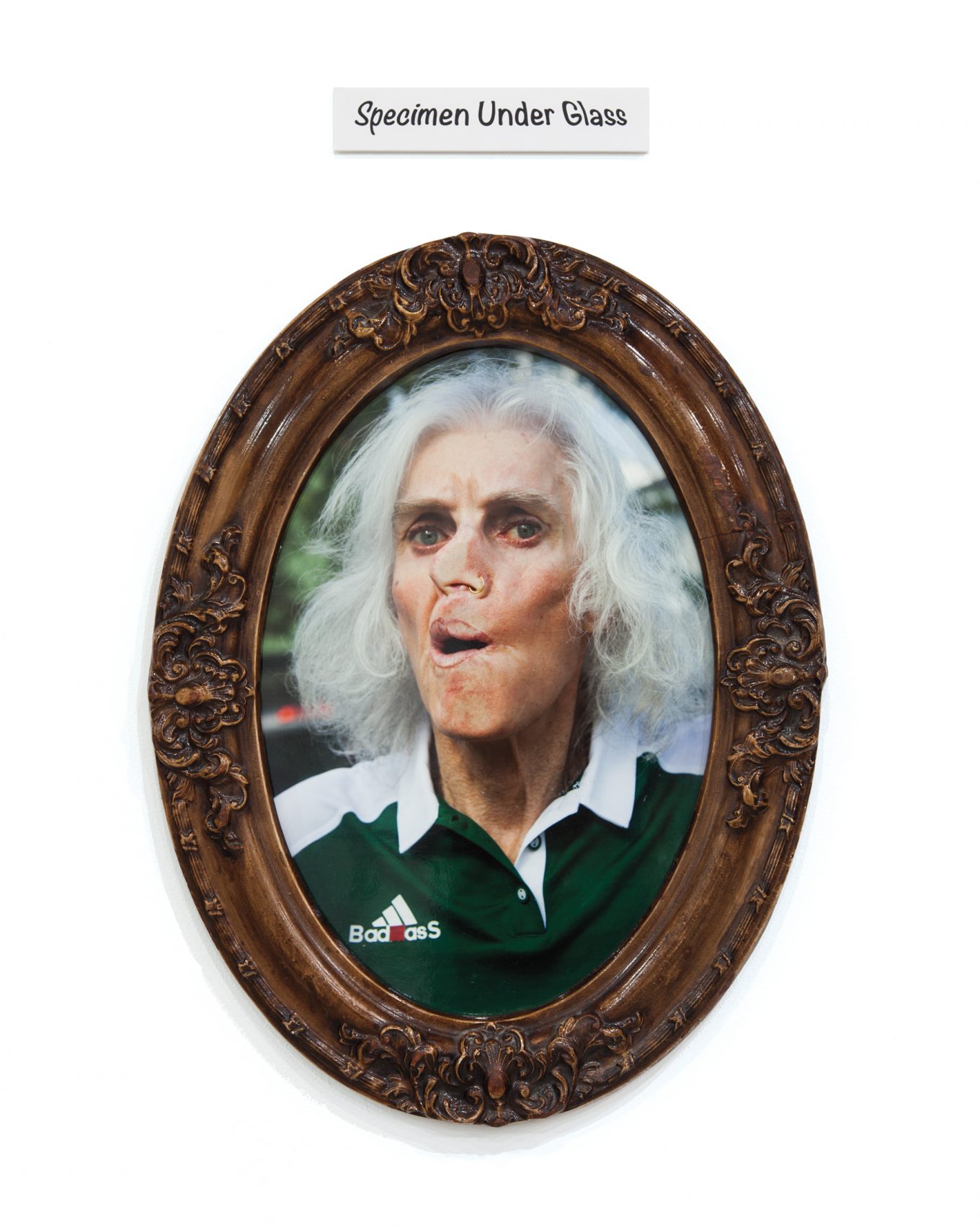

Pippa Garner, Specimen Under Glass, 2018, Framed photograph, 25 x 18 1/2 x 1 1/4 in. Courtesy of Redling Fine Art.

On Sundays, Misc. Pippa Garner takes one of her pedal vehicles for a cardio climb into the hills above her home in Long Beach. Built on the chassis of a recumbent bike, her car rides low to the ground. The woman at the wheel is six-foot-three; the hair under her helmet is long and white. She wears black spandex racing pants that reveal the wood grain of American oak inked below her left knee. Underneath her clothes are more tattoos—a blue G-string stuffed with Monopoly money and a pink bra on the C-cup breasts she got in Portland, Oregon. On her shoulder is the phrase “I is a ass.”

What she likes about California, Garner tells me, is that, “It’s just so monotonous. The sky’s always the same pale blue, except in the fall or spring when everything looks pale gray like an overexposed map.” She is attracted, she tells me, to “that quality of blandness. Somehow it acts as a backdrop for the absurdity that California seems to attract. Or used to.”

Garner relishes disturbing this monotony. As a satirist of consumer culture, she aligns herself with the fool found in medieval courts. “The fools were close advisors to the king. They were wise. They had perceptions. They were artists. They had a sense of how things were coming together or falling apart, because they could maneuver around the court and see what was going on, and they were very valuable to the king.”

Part of a boomer generation of West Coast artists, Garner’s circle during the 1980s included Ed Ruscha and the radical art and design collective Ant Farm. Garner (then known as Phil) gained attention for her performance, design, and video work at galleries and museums, such as the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, and appearances on The Tonight Show, The Today Show, and The Merv Griffin Show. Garner is the author of Philip Garner’s Better Living Catalog (1982), and Utopia . . . or Bust! (1984).

In 1988, Garner began a feminization process that included hormone replacement therapy and sex reassignment surgery. As an extension of her practice altering materials of mass production, Garner’s approach to gender transition demonstrated her experimental attitude, prankish sense of humor, and way of queering everyday objects. Collaging masculine and feminine traits in her own body, Garner also transitions between the twentieth and twenty-first centuries—between Duchamp and ORLAN or digital assemblage artists Laure Prouvost and Ryan Trecartin. The following interview was conducted by phone in January and February 2017 and has been edited for clarity.

NICOLE MILLER: The automobile is a recurring motif in your work. How did you get interested in cars?

PIPPA GARNER: I have this thing about enclosures. All creatures have to hide to protect themselves from the elements. Humans, with their bare skin, have had to be more resourceful. But our obsession with buffers has grown out of control, and the automobile is the most absurd and prominent symbol of that. It’s ridiculous. People drive to the market three blocks away in three thousand pounds of machinery.

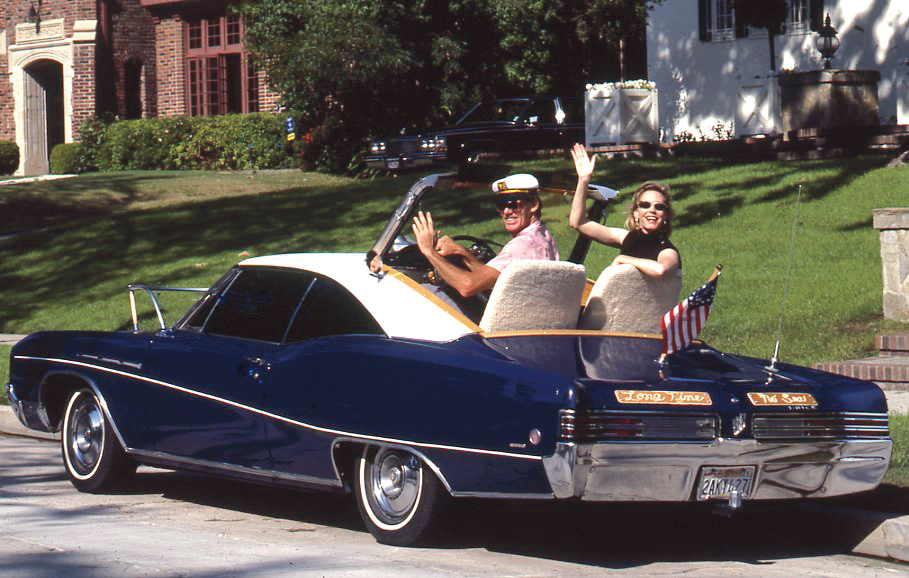

Pippa Garner, Nauti-Mobile (Two if By Sea), 1986. Mixed materials (including a 1986 Buick LeSabre and 1968 Datsun), approx. 220 x 80 x 100 in. Courtesy of Redling Fine Art.

MILLER: When did you start using the automobile in your art?

GARNER: As a kid, I drew constantly and made things, but I didn’t know any artists. My father was really straight. He was an ad man for McCall’s magazine. My mother was sort of a frustrated housewife who dropped out of college to get married during the Depression. She got her master’s degree in English much later, but they were not people that had any connection with the art world, and nobody else that I knew did either. I felt like I was doing something that interested me, but I didn’t know where it was going. That’s still the way it is.

I came out to California in 1961 to go to ArtCenter College of Design, which at that time was the leading supplier of car and industrial designers. The whole curriculum was aimed at putting you into a corporate job. My parents couldn’t deal with the idea of artists, so that was the compromise. They thought that if I was going to be an artist of some kind, I could work for a big company. The other students there just lived cars—we used the term autosexual. It made me feel the absurdity of the whole automobile industry. I refused to stick with the standard industrial designer curriculum, which didn’t include anything like figure drawing, which I really loved. I started doing things that were making fun of design.

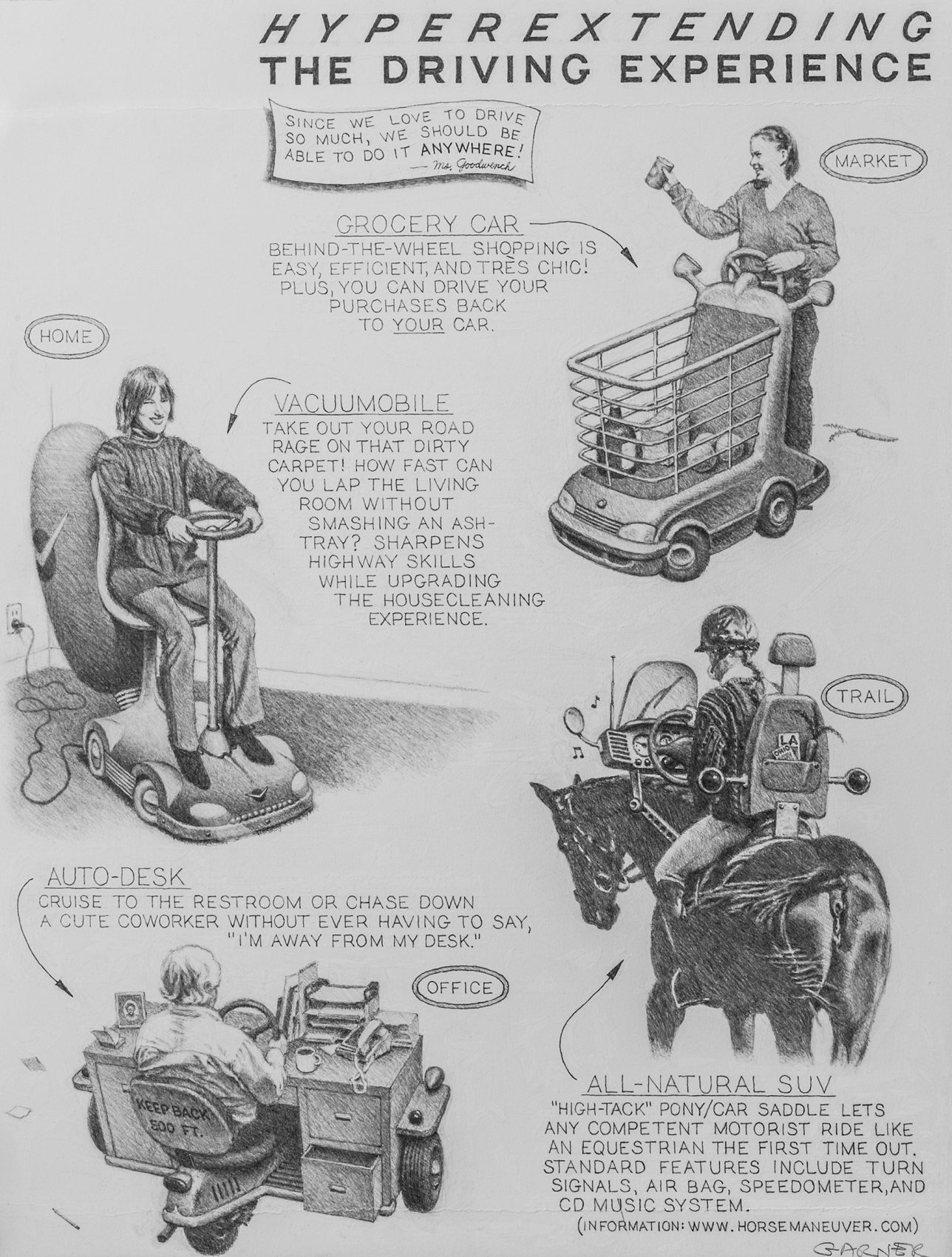

Pippa Garner, Hyperextending, circa 1990. Pencil on paper, 14 1/2 x 11 in. Courtesy of Redling Fine Art.

MILLER: How did you develop your satirical point of view?

GARNER: In 1965, while I was at ArtCenter, I got drafted. This was during the Vietnam War. I’d used up all my student deferrals, so I spent two years in the military. When I came back, I was totally motivated and super productive, and the satire part of it developed even further. I built this car—a typical big Detroit-looking car that gradually morphed into a male figure lifting its leg on a map of Detroit. That’s when I ran into trouble with the school officials, and they asked me not to return.

MILLER: How did you transition from industrial design to making work for a fine art context?

GARNER: I did some commercial work for West Magazine, the Sunday magazine of the Los Angeles Times, which was winning design awards at the time. Then I started to meet bona fide artists. Ed Ruscha was a good friend during the 1970s and ’80s. His studio was not far from where I lived. We used to have dinner and hang out, and he was already quite well known. During that period, I was married to a really good painter, Nancy Reese. There were a lot of artists in LA during the late ’70s and early ’80s who were just getting started. The whole thing was open to new talent. At that time, I became self-conscious about whether I was an artist or not. I watched artists making work for the galleries, working to advance in the art world—I hate that term. I thought, Gee, I’m not part of that. I was really compelled to do stuff for larger audiences. It was in the back of my mind that what they were doing was more sophisticated, and I knew I should be doing that, but I couldn’t think that way. It was never resolved, really.

I read a book recently on the history of the Volkswagen. Every so often you see one of the old Volkswagen Beetles, and it looks so safe and so appropriate. That is a machine designed to move human bodies. It has a happy face, and it’s small, and it just looks right. The original designer, Ferdinand Porsche, was an artist. If you look carefully at one of his cars—the lines, the sculpted sections in the hood, all the little details that pull it together—it’s a magnificent work of art. It doesn’t look like anything else that ever was done. So I think it’s possible to be a highly creative artist in any medium you want, and it can be a commercial medium.

Pippa Garner, I’d Rather Butter Myself from the series Shirtstorm, 2017. Mixed media on T-shirt, dimensions variable. Courtesy of Redling Fine Art.

MILLER: For years, you’ve been making graphic T-shirts using found images and collage. They remind me of internet memes. Why did you adopt the T-shirt as a medium?

GARNER: The whole point of the T-shirt is to work in an unexpected, throwaway medium. I like the format because it’s very graphic and the fabrics are interesting, and I like the contour, because the body is part of the image.

The T-shirt has a strange history. Through most of the 1950s, the T-shirt was underwear. Men dressed up in wool suits to go to work every day, whether they lived in Sarasota or Detroit. They wore hats. Women wore high heels. It was daring for a rebellious young person to wear a T-shirt as an outer garment—think of James Dean with a pack of cigarettes rolled up in the sleeve. But nobody put an inscription on the T-shirt. That would’ve been trash, like a sandwich board that people wore during the Depression, parading up and down in front of a restaurant to get a bowl of soup. It wasn’t until the 1960s or even later that some genius or jackass realized that people were walking around with a potential billboard on their clothing.

I buy shirts on eBay that have an image that I can use as a basis. I use fabric glue and different things to extend my work, but it’s all just collage. Several years ago, I started having trouble with my eyes, and it turned out I have advanced glaucoma. The eye strain is so great that I can’t draw for very long, but I can do these things with the graphics.

Pippa Garner, Crowd Shroud, 2017. Wheelchair, wood, paint, vinyl, two-way mirror, bicycle lights, 54 x 42 x 19 1/2 in. Courtesy of Redling Fine Art.

MILLER: When you showed your T-shirts at Redling Fine Art in 2017, you also created a performative installation called Crowd Shroud, which was a wheeled enclosure where you sat in the gallery, hidden from view. How did that work reflect your interest in the body?

GARNER: I’m fascinated with odd forms of human mobility. I was thinking of the sedan chair, which was used in London through the late nineteenth century. Apparently, the streets of London were so filthy that the wealthy would hire someone to carry them through the street. It was an image of class extremes, with the aristocrat being highly visible while being carried in public by a couple of drudges. Today, the tabloids have made it so that celebrities try not to attract attention. They want to be discreet when they’re in public. They wear big sunglasses and they have security. So I made a modern iteration of the sedan chair—a vehicle with mirrored, one-way windows that I could sit inside with only my feet showing.

MILLER: There’s something voyeuristic about your position inside the vehicle. I wonder how you feel about public visibility or camouflage.

GARNER: I’m an introverted exhibitionist. Artists are generally introverted, because it’s an observer’s vantage point, so you can’t fully assimilate into culture. You have to stay where you’re not altogether part of things. You’re on the edge watching other people and making some sort of statement about that. But I also like to be on display somehow. That was one of the motivations of the sex change. With a sex change, you’re making a visual statement.

MILLER: When you began to transition in 1988, what visual statement did you want to make?

GARNER: At the height of my career in LA, in the late 1970s and ’80s, my image was really masculine. In my books and in my talk show appearances, I played the role of the eccentric small-town inventor. In a way, I was making fun of masculinity, but I didn’t realize that’s what I was doing. I wasn’t ready to see it that way yet, but I was actually setting myself up for rejecting masculinity on some level. Transgender is a common word now, but at that point it was really freaky. That wasn’t really my motivation, but it certainly didn’t turn me off. I gravitated toward it. I liked the idea of trying something unknown.

Pippa Garner, Power to the People (pencil sharpener), 2018. Mixed media, 6 x 11 1/2 x 5 in. Courtesy of Redling Fine Art.

MILLER: Can you talk a bit more about why you wanted to transition?

GARNER: I had some of the traditional issues that are associated with gender transition, but I never felt born in the wrong body, which is the clichéd phrase that turns up in every biography or interview with a transgender person. I just felt like there was something that didn’t fit. If I had grown up in this age, it might’ve been recognized in childhood, like some parents are doing now.

MILLER: What might have been recognized?

GARNER: That I had gender dysphoria, as it’s technically called. The need to not be channeled into either male or female.

MILLER: So you have experienced gender dysphoria?

GARNER: Well, yes. I think it was there. Because of the timeframe, it wasn’t something that I could allow myself to accept. I had to shut it out. I reached a time in my middle life when I had this constant frustration with the male sex drive dominating everything. I wondered whether there was some way to experience something else, so I started talking to transgender people, mainly sex workers on Hollywood Boulevard, and I did some reading on the subject. It seemed to me that I could experiment with female hormones without any lasting effect. If I didn’t like what it was doing, I could quit. When I started taking hormones in 1988, all this pent up sexual energy fanned out into sensuality. I gained a wider spectrum of feelings.

MILLER: How did your experience with hormones shape the art you were making?

GARNER: After five years of taking hormones, I realized I was never going to go back and assume the male endocrine profile—but I wasn’t thinking about becoming a woman. You can feminize or masculinize, but you can’t become a woman or a man. That’s genetic as far as I’m concerned. When I decided to go through with sex reassignment surgery, as they called it then, it became more of an art project. I was always really body impulsive or body obsessive. All transgender people are, I would say, and that’s one thing that separates the transgender community from gays and lesbians. Body obsession has to do with how you look. The body becomes a sort of product. I was working with consumer appliances and products, and I thought, Hey, I’m a product too. I have this whole structure that’s designed to hold up my head—systems and subsystems that seem tuned to each other—and it has a lifespan just like other things. If I’m no different from anything else, if my body is assigned to me for a certain time, why not play with it?

MILLER: I wonder about the risks of treating the body like a product or a commodity. I’m thinking about the ways that commodification is often imposed on the body by corporate culture, or the potential health risks of body modification.

GARNER: When I got my breast implants twenty-five years ago, it had an incredible psychological effect. At first they were uncomfortable. Gradually, they became part of my body, like a prosthetic. You psychologically accept and bring something like that on board. You think, That’s as much me as my liver, even though it’s just silicone. I had one surgery in Brussels and another in Portland. I wanted to do all these surgeries under local anesthesia, because I wanted to be present and see what was going on and be part of the process. To me, it was like collaborating on a project—though with a surgeon as opposed to an artist. They go in there and pull and tear and bang and yank—it’s like working on a car. The body is very resistant, and it’s made of tough components. In order to make a change in it, you have to be aggressive. It was surprising, because I always thought of it as this very delicate procedure, like a dentist doing a filling. They said there was a twenty percent or lower chance that I wouldn’t be able to orgasm once I had the surgery. It turned out I was in that category.

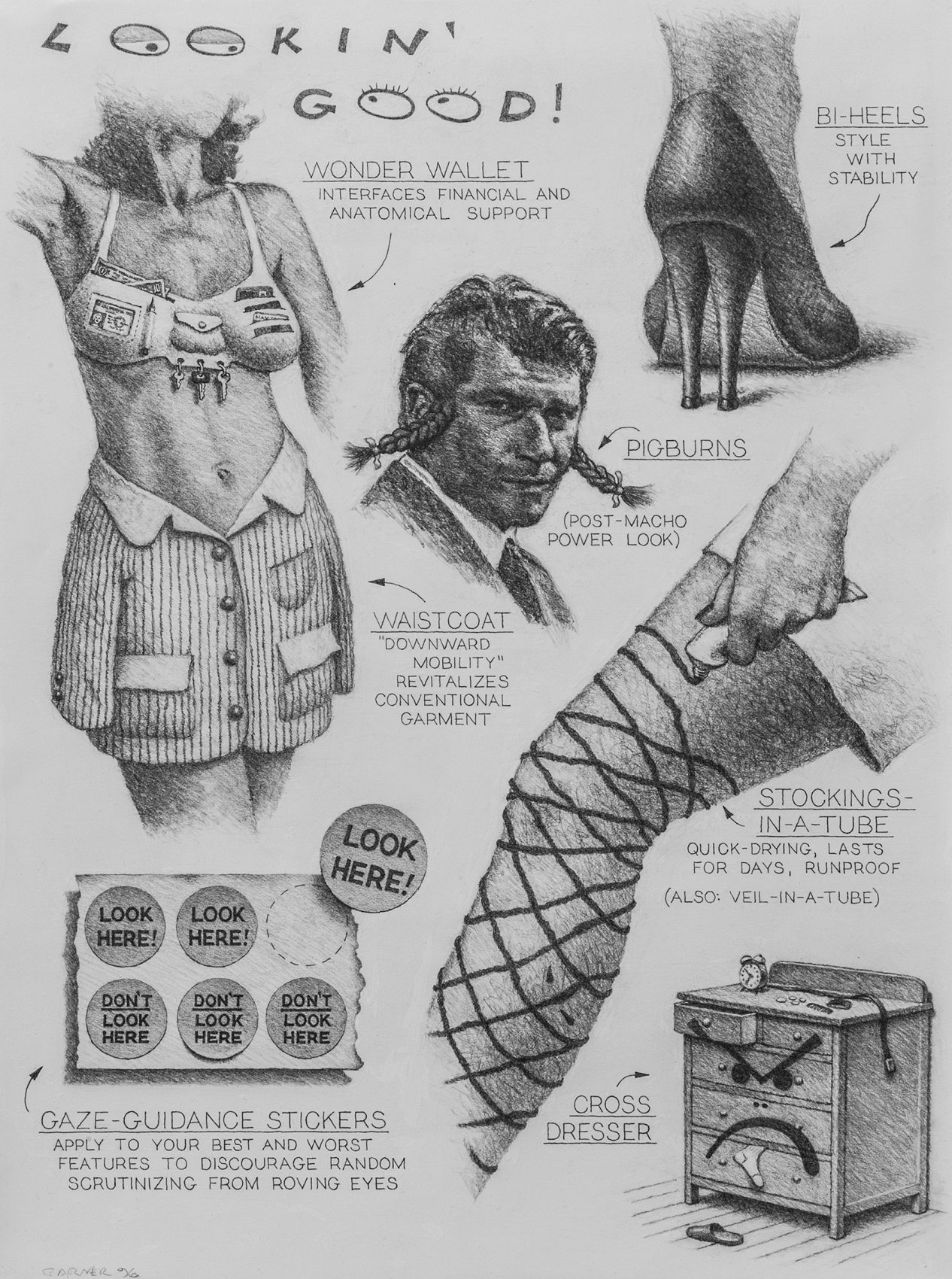

Pippa Garner, Lookin’ Good, circa 1990. Pencil on paper, 14 1/2 x 11 in. Courtesy of Redling Fine Art.

MILLER: If you’d known prior to the surgery that you would never again have an orgasm, would you have gone through with the surgery?

GARNER: I can’t answer that. It’s something I’ve asked myself. Again, the art idea came into play. At that point, I’d decided to do something that was really disorienting. I always felt like I was the most creative when I was the least comfortable. It’s the edge that you need to get that mechanism going, the so-called creative juices flowing. I had the feeling that if I did something that drastic, I’d always be a bit on the outside looking in and have to adjust to that and honor that, and it might stimulate a level of creativity that I’ve never known. I think it paid off.

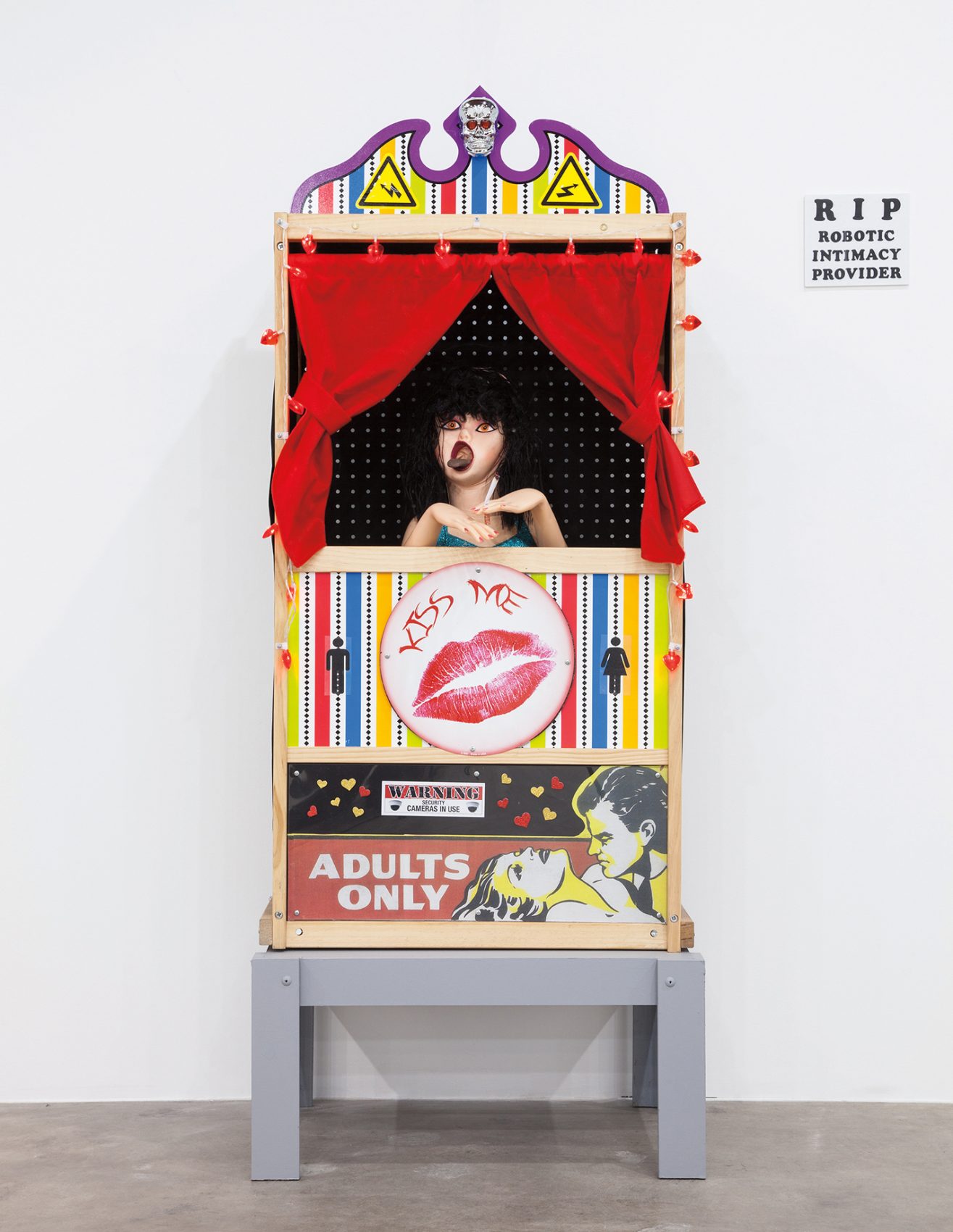

Pippa Garner, R.I.P. (Robotic Intimacy Provider), 2018. Mixed media. 64 1/2 x 27 x 19 in. Courtesy of Redling Fine Art.

MILLER: How did your artist community respond to your gender transition?

GARNER: I lost a lot of friends. They were a pretty macho group. If anybody really thought about it, my image as a male—the small-town tinkerer in a tweed jacket and bowtie—was a masculine character from the 1950s. People didn’t see it as satire. But when I started fooling with gender, their reaction was, Uh-oh. You’ve gone too far.

MILLER: How does satirical performance play a role in your work now?

GARNER: I have this idea, this sense of being theatrical. That’s very important to me. When I lived in Santa Fe in the early 2000s, I was reading a lot about early cultures. I discovered that one of the common conceptions of creation among prehistoric people was that the male and female sprang in equality from an androgynous godhead. So gender equality was built into early cultures, as far as we know. I wanted to do something that represented this early concept of creation, so I created a triptych of images—which ended up being a Piptych—where I posed as a man, a woman, and the gold-painted god that they sprang from. It was all very tongue-in-cheek. I worked with a videographer in Santa Fe to create the images, and then I decided the obvious next step was to bring these two characters to life. So we created a series of short videos where I played both genders. The point was to try to put some absurdity in the whole idea of gender stereotypes.

MILLER: How do you relate to the wider trans community? Have you found acceptance for your satire among other trans folks?

GARNER: No. In the Bay Area, where I was living when I had my surgery, there’s greater acceptance of variations in gender. I expected to find people who had a creative attitude about the whole thing, who were transitioning because they were fascinated with it rather than because they were driven to it. But what I found is that they weren’t at all open to my attitude. So I just said, Fuck it. I’ll keep it to myself.

In Long Beach, where I live now, I’m pretty much isolated. It’s a relatively new experience for me, because I’ve always had people that I was close to. It’s partly that being transgender is very isolating, because it’s a fringe thing. Only .3% of the population identifies as transgender, so people don’t really know how do deal with it. You don’t arouse the antagonism you once would have, but it’s not something that draws people. I miss that period during the 1970s and ’80s when there were so many people who were doing all kinds of interesting things. It was such a rich environment. But I’ve got enough stuff stored away now. I’ve had enough experiences in my life that I can pretty much go on what I’ve got. I don’t need to have the stimulation to do the work. But it means being alone all the time.

MILLER: This is making me think of where we started—with the automobile as an enclosure that’s potentially isolating.

GARNER: I think of the body as another enclosure in a way. It contains all this stuff that you can’t see, but you know it’s in there. You’ve got your heartbeat. You can sometimes feel your organs. When you go to the gym, you feel individual muscles getting exhausted. Maybe my work is based on a need for communicating, of being aware that I’m an enclosure full of this stuff, that I’m a thing that’s a container for other things. I don’t know if there’s some special aspect of that that I connect with more than most people. I think it’s also ego of some sort. I still have this sense of wanting to experiment with myself. I think of my body as art, as a resource, as an object—objectification is supposed to be a bad thing, but I love it.

Pippa Garner is an artist and author who lives and works in Long Beach, California.

Nicole Miller is an art and fiction writer living in Brooklyn. She is co-editor of the digital arts journal Underwater New York.