Drew Heitzler regularly moves between sculpture, painting, photography and film, sometimes making the work with his own hands, sometimes contracting it out, and sometimes appropriating it as is. His output to date bespeaks no ongoing commitment to any one medium, tool or technique, and neither does it reflect a consistent thematic orientation, or at least not one that can be easily grasped. Surfing, structuralist cinema, paranoid literature, comic books, motorcycles, and land art are just a few of the topics that have made an appearance. On first pass, one might imagine that their only point of convergence is the artist himself, that these are simply the things he is interested in, and that they thereby amount to a kind of deflected self-portrait. But Heitzler is not really that kind of artist—the kind that Walter Benjamin designates as lyric, in reference to Baudelaire, for instance. Rather, Heitzler sits closer to the epic end of the spectrum: a broad range of material is gathered and processed, but it does not wind up indelibly marked with the artist’s psychic signature.

The epic work is characterized, first of all, by a multiplicity of characters, each of whom receives a fair measure of attention from the author or artist, as in the process of representative government. In this sense, such works are inherently political; they are sites set aside for the airing of often-divergent worldviews that are not so much invented as reordered into a social whole, or the semblance of one.1 The second defining trait of the epic is its broad historical scope. Such works tend to exceed the limited range of any individual’s experience of life in order to plumb our collective experience over the long range. If we take the works of Homer as our model, or even the Judeo-Christian Bible, then we can say that epic works always concern the formation of societies over and above any of their singular subjects. If there is to be a hero, then it is as a prime mover of the social process. Crucially, such figures are not immediately identified, as in the lyric mode, with the “I” of their authors. In Benjamin’s writing on Baudelaire, whom he characterizes as a lyric poet in the “inhospitable, blinding age of large-scale industrialism,” particular attention is drawn to the imprinting of the crowd as a “hidden figure” within the verses.2 Baudelaire’s words take shape, Benjamin suggests, as if on the big city street, in and amongst the jostling masses; the influence of all these others is pervasive, and yet they are rarely mentioned by name.3 The external world exists only to enrich the inner life of the artist with impressions and affects. Here, then, what is described is a state of being that alternates between immersion in and exclusion from society, whereas, in epic works, a more nuanced dialectic of inside and outside comes into play. The narrating “I” of the epic occupies society in a way that might be related to that of the embedded journalist; it disperses itself over the multitude while simultaneously maintaining a bird’s-eye view. On the other side of Baudelaire, Benjamin locates the epic theater of Bertolt Brecht, where the insular formalist impulses of modernism are consistently checked by questions of collective organization.4

Heitzler’s work is similarly poly-vocal, to employ a favorite term of the 1980s, and if we can say that he largely composes this work with the voices of others, it is not to claim full aesthetic ownership over them. Composition here takes the form of a kind of diagramming; it is a mode of organization that operates on behalf of associative freedom and political speculation. In this regard, it is perhaps worth noting Heitzler’s various sideline occupations as a gallerist, bar-owner, and curator, all of which provide a literal analog to the social-collective element in his art. In 2003, together with his then-wife, artist and dancer Flora Wiegmann, he opened Champion Fine Arts in Williamsburg, hosting a series of artist-curated exhibitions by a number of his emerging peers. In 2004, Heitzler and Wiegmann relocated to Los Angeles. They brought Champion with them, expanding its roster to include a greater number of West Coast representatives. In 2006, in partnership with the artist Justin Beal, they opened the Mandrake, a bar that remains in operation in the Culver City arts district. After over two decades of “relational aesthetics,” we are perhaps no longer inclined to consider these venues—the white cube of aesthetic contemplation and the dimly lit lounge of intoxication—in terms of their difference; yet, in this case, their particular symmetry still stands out. In press reports, Champion was consistently characterized as a “club house,” a socially boisterous counterpoint to the normally hushed and inwardly focused precincts of art. And, for its part, the Mandrake has always functioned as both a regular watering hole—a “public house”—and a more targeted addendum to art-world activities, hosting exhibition after-parties, artists’ lectures, book releases, screenings, and discussions. Both the gallery and bar may be described as community-building projects; yet, for Heitzler, they are also a crucial source of material for his own works, which tend, on the whole, toward the darker, non-democratic, un-transparent and anti-convivial end of the political equation.

Endless Bummer / Surf Elsewhere, installation view, Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, July 3–August 28, 2010. Courtesy of Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo.

In preparation for a group show that Heitzler curated for Blum & Poe in the summer of 2011, he led a reading group at the Mandrake on Thomas Pynchon’s then-recent novel Inherent Vice (2009).5 The exhibition was titled Endless Bummer: Surf Elsewhere, in a downbeat nod to the 1966 documentary celebration of the wave-riding lifestyle, Endless Summer, and its conceit was that all of the works included would conform to the sensibility of the South Bay-dwelling detective of Pynchon’s book, Larry “Doc” Sportello, here reimagined as an art collector. Accordingly, whatever this character is drawn to in the author’s recounting determined the process of curatorial selection: sun and sand, the sublime expanse of the ocean, bikinis, surfboards, and pot—all faintly clouded with intimations of intrigue. Highlights of the show included Anne Collier’s appropriations of West Coast lifestyle imagery (California Poster, 2007), a marble surfboard by Reena Spaulings (Mollusk [Rosa Portogallo], 2009), and Roe Etheridge’s photograph of a dope-smoking redhead (Sarah Beth with Pipe, 2006), alongside characteristic offerings from such éminences grises of the “cool school” as Billy Al Bengston, John McCracken, and Ed Ruscha. The works of all the featured artists, a number of whom were drawn from the Champion “club” and participated in the reading group, were in this way shoehorned into a predetermined narrative scheme.

It is standard procedure for a curator to speak through the works of artists, to ventriloquize their production, but what is perhaps more unusual in the case of Endless Bummer is that the overriding voice was not Heitzler’s but that of a fictional construct, and openly proclaimed as such. Literature, with its proliferation of alter egos, is a model that can productively disrupt the expected relations of expression and authenticity within the context of art exhibitions, and Inherent Vice provides a particularly complex and recursive instance. Significantly, the novel is set at the start of the 1970s, right around the time, as well as the place, that Pynchon wrote his breakout novel Gravity’s Rainbow. Pynchon’s at once introspective and evacuated, drug-addled detective effectively retraces the author’s steps to the “scene of the crime”—or its writing—and thereby offers a lyrical meditation on the epic intentions of that earlier book. Gravity’s Rainbow has long served as a conceptual touchstone in Heitzler’s own work, and here the artist, via Sportello, channeled the voice of Pynchon rereading himself, and then projected the outcome onto the works of all the artists in his show.

Heitzler, who grew up in South Carolina, relocated to Los Angeles for a number of reasons; perhaps the most pressing one was to get close to the waves—he rented an apartment in Venice and set up studio in El Segundo— and this has as much to do with his enthusiasm for surfing as for the writings of Pynchon. In other words, the move was an attempt not just to escape the old social pressures that we once associated with congested urban centers, but also to meet head-on the new, more invisible and perhaps more pernicious pressures that have dispersed toward the outlying zones. “Tip the world on its side and everything loose will land in Los Angeles,” Richard Neutra famously proclaimed, invoking a city populated as much by easy-going free thinkers as ideological fundamentalists: loose nuts. The sinister global plot that Pynchon intuited while composing Gravity’s Rainbow in the “mellow,” i.e. outwardly a-historical and de-politicized, atmosphere of Manhattan Beach may have originated elsewhere, but Inherent Vice makes it plain that it landed here, and moreover that California was perhaps a central base of operations. Of course, the beachside idyll of the West Coast was a hotly contested terrain right from the start—apparently not everyone is entitled to la vita nuova—but by the 1970s the hostilities had reached a boiling point. Pynchon’s return to those days unfolds amidst televised reports of the Charles Manson trial, the utopian dream of starting over from scratch having already degenerated into a terroristic death trip. In the novel, starting over is increasingly recast as a process of taking over—the land, its resources, and ultimately the minds and bodies of those already there. “Was it possible,” Pynchon asks, “that at every gathering—concert, peace rally, love-in, be-in, and freak-in, here, up north, back East, wherever—those dark crews had been busy all along, reclaiming the music, the resistance to power, the sexual desire from epic to everyday, all they could sweep up, for the ancient forces of greed and fear?”6 In his book, the logic of the hippie commune, now comprised strictly of the brainwashers and the brainwashed, is extended to the whole range of industries that dominate Southern California in the postwar years: entertainment, marketing, information processing, aerospace, real estate, psychiatry, pharmaceuticals, body-building, cosmetic surgery, and self-help, a tangled web of competing or synergistic cults.

Endless Bummer / Surf Elsewhere, installation view, Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, July 3–August 28, 2010. Courtesy of Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo.

In Endless Bummer, it was first of all the title that prompted a dismal read of even the most feel good works on view. Art is, after all, freighted with historical memory, and also sometimes fraught with it. This is the element that Heitzler drew out and emphasized in his exhibition scheme: whether they asked for it or not, all of the included works would be implicated in the great disasters of the twentieth century. If we agree with Friedrich Kittler’s claim that all information technologies originate in war, then any artist employing a medium that emerged along the line of development between the typewriter and computer terminal—phonography, film, radio, television, etc.—is automatically tied to the “military-industrial complex.”7 In the case of California, however, the links are more explicit and damning. From the first moment, the “L.A. Look” is tainted: the regionally representative movements of Light and Space and Finish Fetish, with their use of new chemical compounds, synthetic colors, and advanced engineering, spotlight the artist as the most immediate beneficiary of the midcentury dismantling of the war industry and its dissemination into the private sector. Moreover, from the “Weimar diaspora” of aesthetes and intellectuals in the interwar years to the postwar brain drain of the German technocracy, the culture of California would become increasingly haunted by specters of fascism. Behind every smiling beach bum lurks a “Surf-Nazi.” This ominous figure, glimpsed on the horizon of Endless Bummer, would become the leitmotif of Heitzler’s most recent solo show at Blum & Poe.

This exhibition was titled Pacific Palisades, after the affluent Los Angeles neighborhood, perched on the canyons of the west side and overlooking the Pacific, that is still widely remembered for the exiles and émigrés who settled there after fleeing Germany and Austria under the Third Reich. For the occasion, Heitzler produced a lengthy piece of critical writing that bears the same title and is, in its content at least, academically credible and compelling. In the introduction, however, it is described as an “art book” and, true to form, it was here displayed on a narrow pedestal as a limited-edition work. But perhaps more substantively, its status as art has to do with its method of construction, which is explained in the opening pages accordingly: “It is mostly cobbled together from cut and paste Wikipedia pages, online sourced magazine articles, and plagiarized texts.” Again ventriloquizing and/or speaking in tongues, the artist traces the genealogy of the Surf-Nazi to several key sources.8 One is the Hungarian Mickey Dora, arguably Southern California’s original star surfer, whose custom-made boards featured a prominent swastika. Another is the Pacific Model Homes Company, which employed this same sign as a logo on their mass-produced surfboard line, and kept it there from 1930 until 1937 (when it was removed, for obvious reasons). And then there is the former military engineer Bob Simmons, who began transitioning wood surfboard design toward plastics with the help of polyester resin, “a German wartime secret,” Heitzler notes in his text, “stolen by the Allies in 1942.” On their own, these bits of information could be written off as coincidental, but they add up. “Everything loose” that is “tipped” into Los Angeles, to resume Neutra’s wording, appears overwhelmingly to come down to the ruins and fragments of Germania and, before that, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which here become grounded as cultural bedrock. From the swastika cut into Manson’s forehead to all the military regalia—“German eagles, iron crosses, SS lightning bolts”—donned by the hardcore bands of Orange County and their fans, this particular symbology reappears again and again, suggesting that California is not so much a land of new beginnings as eternal recurrence, the site of a catastrophic history set on repeat.

Drew Heitzler, Pacific Palisades, 2015. Edition of 5 + 2 AP. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/ New York/Tokyo.

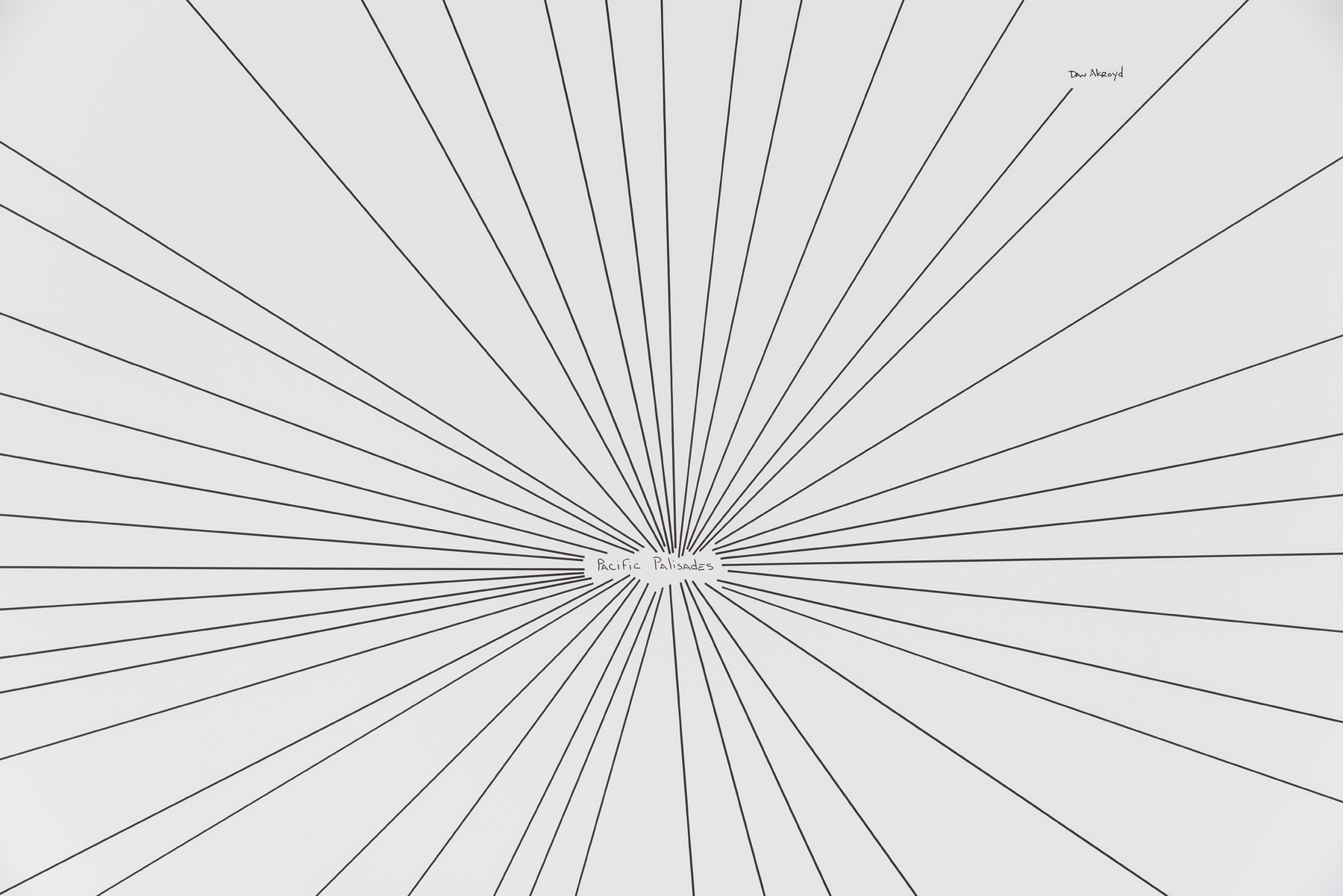

Heitzler has mined the geo-political terrain of this region in previous works, such as the video Untitled (Ladera Heights) (2007), which juxtaposes footage of a pumping oil derrick with picture-postcard shots of palm trees as a ghostly reminder of the days when, for instance, the paradisiac view of Venice Beach actually was marred by the exposed machinery of coastal drilling. However, it is only after Endless Bummer that the “German Question” would begin to take center stage.9 This is not to suggest that Heitzler simply wants to blame the Nazis for everything that went wrong here, for as the beam of Teutonic influence expands from its point of origin, it grows increasingly diffuse, ambiguous, polarized. After all, California also inherited a legacy of anti-fascism, which then formed the basis of its various youth, sub and counter-cultures. This particular turn was at the crux of Pacific Palisades, and yet Heitzler’s take is again circumspect. As has been amply demonstrated by the passage of the beatniks, hippies, and punks through the Golden State, even on the extreme anti-establishment side of the fence, one is not any more likely to come out from under the authoritarian shadow. The point was immediately clinched in a massive diagram, a hand-drawn sketch enlarged and transposed in adhesive vinyl onto a whole wall of Blum & Poe’s upstairs gallery, which served as an index or key to the show. Projecting outward from a central point, labeled “Pacific Palisades,” via a series of radiating lines, this work maps the trajectories of a wide variety of cultural producers that crossed paths in this place. Included are such pantheon figures as Theodor Adorno, Arnold Schoenberg, and Thomas Mann; some still-controversial and cultish types, like Kenneth Anger, Frank Zappa, and Manson; and, finally, those who, through techniques of brand incorporation and franchised merchandising, have successfully worked to mainstream radical ideology. Here we are given the founder of Scientology, L. Ron Hubbard, the communications network guru, Jon Postel, and the producer of The X-Files TV show, Chris Carter, as well as a host of institutions listed only by title: the Rand Corporation, Jet Propulsion Laboratories, The Human Betterment Foundation, etc. The idea of sinister cooption that hangs heavy over Pynchon’s Inherent Vice is again suggested here, but the resolutely nonhierarchical and atemporal form of Heitzler’s mapping also suggests otherwise. His is a free-floating constellation, and as such, imprinted with a kind of fatalism that is imminently reversible, that tracks backward. One could say, for instance, that the ideological structures of hippiedom were not defeated by corporate powers so much as fulfilled in them.10 The names are connected across lines of kneejerk opposition in a way that points toward the dialectical principles of montage.

Drew Heitzler, Pacific Palisades, installation view, Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, July 2–August 22, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo. Photo: Joshua White.

Although Benjamin never states it outright, he was likely thinking epic when he wrote about filmic montage in “The Work of Art in the Age of Technological Reproduction.”11 In this essay—which he composed, not coincidentally, while on the run from the Nazis—we observe the reappearance of the key themes of interruption, estrangement, and audience training that inform his work on Brecht, now projected onto the standard operating principles of technical media. Heitzler’s work on the whole can also be viewed through this lens, yet here the apparatus of cinema, Benjamin’s case in point, confronts a revolutionary scene that has already been televised and is cycling through reruns. The works that comprised the bulk of Pacific Palisades wrap around most of the remaining three walls of the gallery.The series of framed red, yellow, and blue monochrome prints bear juxtaposed images pertaining to the various points of aesthetic and ideological confluence charted on the key-map. Intimately scaled, they appear from a distance handmade but are in fact the result of a rote digital reprocessing of photomechanical source material. All are from 2015 and titled Study #1 for Paradies Amerika after a likewise California-themed five-channel video piece, produced one year earlier, from which their contents have been derived. First screened at Marlborough Chelsea in 2014, Paradies Amerika features a selection of mainstream, genre-based, experimental, and educational films projected side by side and occasionally crossfading. Merging strictly extant footage, this is a montage-film through and through, and the still pictures that Heitzler draws out of it focus on the most salient moments of montage: the edit, the dissolve, the overlap. In one telling instance, a close-up of a skull from the Richard Burton-helmed version of Doctor Faustus (1968) merges with a statuesque shot of Mickey Dora and a colleague climbing atop their surfboards from a film in the Beach Party series.12 This conflation of high and low registers barely deserves mentioning, however, at least not as a means of leveling the class-based assumptions that might still attend to each side. Benjamin’s thoughts on the socially redeeming aspects of distracted learning, the forging of a collective unconscious by cinema, always implied a shared mass reception. But here we are clearly dealing with more privatized forms of the psyche. In their diminutive size and their sleek white-frame “cladding,” these works relate less to the silver screen than the TV set or laptop computer. These are the sorts of images captured while scrolling, rolling over each other in time to their scan-rates. The determined intentionality of celluloid cut-and-paste is already far behind them; as Heitzler has suggested, they are more like the products of channel surfing.

Drew Heitzler, Study #1 for Paradies Amerika (Doctor Faustus/Beach Party), 2015. Solvent and water-based ink on Arches, polyester resin on wood; framed dimensions: 9 9⁄16 x 12 inches. Edition of 2 + 1 AP. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo.

Drew Heitzler, Study #1 for Paradies Amerika (The Information Machine/My Demon Brother), 2015. Solvent and water-based ink on Arches paper, polyester resin on wood; framed dimensions: 9 9⁄16 x 12 inches. Edition of 2 + 1 AP. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo.

The saturated red, yellow, and blue pigmentation of these works points to the primary triad of subtractive color mixing in art; in their stand-alone presentation as monochromes, they take in a modernist lineage that extends from Aleksandr Rodchenko’s zero-degree constructivist canvases, Pure Red Color, Pure Yellow Color, and Pure Blue Color (1921), to Barnett Newman’s painting suite, Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue (1966–70). The conversion of an originally radical avant-gardism into the more depoliticized forms of midcentury modernism might also be recalled here. Heitzler deploys his colors as a kind of painterly veneer over their hyper-mediated, collaged ground, which is partly submerged in the process, and this begs an allegorical reading. Collectively designated as “studies,” these works are paradoxically proposed as precedents for what they actually follow, and in this sense echo the form of his book, which is also spliced together from existing sources, but then formatted to resemble an original manuscript. The old-school typewriter font of Pacific Palisades is a literary analog to the watercolor-like appearance of the “studies”; both suggest authorial primacy, but in an openly deceptive manner, across the great distance of the aesthetic preset of the computer’s font menu.

Drew Heitzler, Paradies Amerika, installation view, Marlborough Chelsea, New York, September 6–October 11, 2014. Courtesy of the artist and Marlborough Chelsea, New York, 2014.

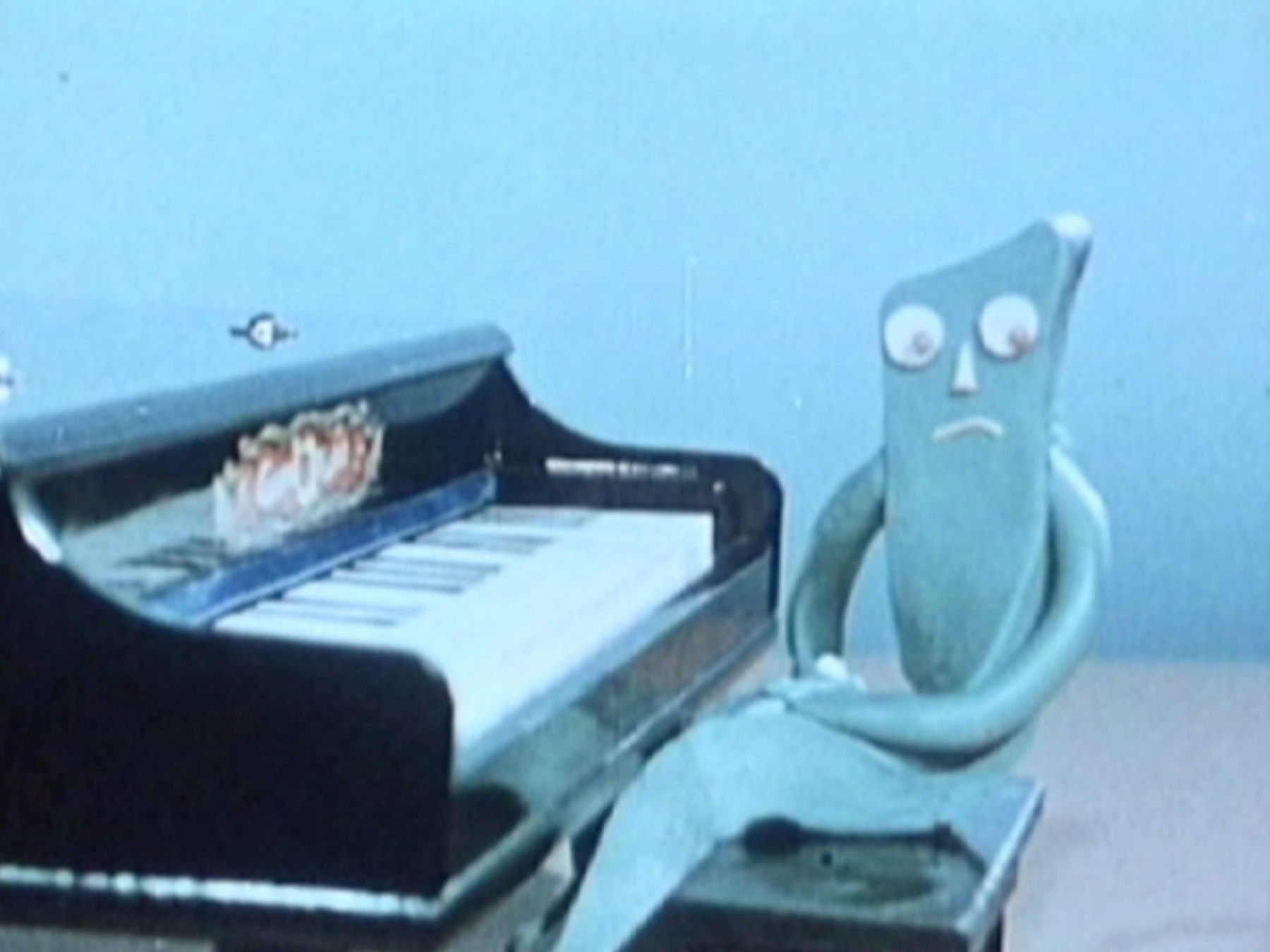

Even when the montage process is more hands-on, as it is in a film projected in a corner of the gallery featuring Gumby, the animated clay character that was created by Art Clokey in the early fifties, the results are no more progressive or, as per Benjamin, “redemptive.” This work is based on an episode that subjects its stop-motion figure to an especially trying piano recital, in which the instrument literally seizes up underneath his fingers. Heitzler proceeded to reedit the original footage so that Gumby appears to be struggling with a whole other repertoire of atonal music, one that begins with Schoenberg and then transitions through Zappa to Megadeth.13 The outward anomaly of this conjunction of innocuous Saturday morning TV fare with an at first advanced and then openly antagonistic musicality is played for laughs, but let’s not forget that Walt Disney, in the 1940 film Fantasia, enlisted Mickey Mouse to explain Stravinsky to the initially recalcitrant masses.14 Gumby and Disney, along with a host of other cartoon humorists—Mel Blank, Chevy Chase, and Tommy Chong among them—also hold a place on Heitzler’s chart of the Pacific Palisades.

Drew Heitzler, California Medley (A piano concerto performed by Gumby:, Arnold Schoenberg, Piano Piece #1, Opus 23/George Antheil, The Airplane/Hans Eisler, Klavierstucke, Opus 3/Ornette Coleman, Lonely Woman/Alice Coltrane, Altruvista/John Cage, Metamorphosis III/LaMonte Young, Study Number 2/Horace Tapscott, Piano Solo 1991/Brian Wilson, Surfs Up/Frank Zappa, The Little House I Used To Live In/Flying Burrito Brothers, Dark End of the Street/ Captain Beefheart, Evening Bell/Neil Young, Cinnamon Girl/The Doors, Crystal Ship/Steely Dan, Babylon Sisters/Black Flag, Screw the Law/Easy-E, Boyz In Da Hood/Megadeth, Tornado of Souls/Slayer, Seasons in the Abyss/Elliott Smith, Lost ‘n Found/ Brian Jonestown Massacre, That Girl Suicide/G-Unit, G’d Up/Beck, MTV Makes Me Want to Smoke Crack/Earl Sweatshirt, Looper), 2014. Video with color and sound, 45 minutes. Edition of 3 + 2 AP. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo.

Like the “grand master” of montage, Sergei Eisenstein, Benjamin was a great fan of Mickey Mouse. He saw the animated character as a figure of youthful promise, one that had absorbed the shock effect of the edit into the very core of his being, his dasein—he is, after all, a creature drawn frame by frame—to emerge not traumatized, but infinitely resilient and feisty. The moribund and merely pliable Gumby is another story, however, and Heitzler compounds his characteristic foot-dragging agony by forcing him to confront the avant-garde lessons of revolutionary fracture, dismantling, and reconsolidation that he ostensibly skipped the first time around. Here, the use of montage reflects less upon the emancipatory body-building version of Benjamin than Adorno’s “after Auschwitz” rethinking of it in terms of “laceration” and suffering. And yet, what stands out in the end is that, in California at least, all such antitheses can be swiftly synthesized. Ask any gym rat: it all comes down to the pain/gain equation. That the last sitting governor of California was an Austrian national, a movie star, and a muscleman brings this line of thought to a perhaps too tidy conclusion, but this is just the sort of thinking that Heitzler’s work prompts.

The complex social web of the epic work is sometimes unwound by way of a hero’s passage. Like Odysseus or Jesus, this is someone who comes from afar to land in the middle of things, in media res, settling in among a people and revealing to them the peculiar nature of what they all take for granted. The epic hero is neither a comic nor tragic figure, both of whom are essentially defined by their blind spots, the first triumphing by remaining blind to the truth, and the second blinded by its appearance and defeated. Rather, as Benjamin suggests, the epic hero is “a wise man,” always learning on the job, adaptable, and hence “an empty stage”—which is also to say, both a nobody and an everyman.15

Drew Heitzler, Drawing for Pacific Palisades (detail), 2015. Vinyl wall drawing, 98 x 349 1⁄4 inches; installed dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo.

In media res: the epic hero is condemned to live not in unfolding, durational time, but between the flashback and flash-forward. Pynchon supplies his “bummer ending” to the “Summer of Love” in 2009, at a time when the paranoid-critical narratives of the 1970s suddenly became ripe for revision as a nostalgic genre. With hindsight, the reader might be inclined to ask just what is it that has been purposefully left out of this account, or imprinted on it as the “hidden figure” to find. The detective who operates in the epic mode is always both a latecomer and ahead of the curve; the crime that has already happened, he knows, will happen again. The point, for him, is no longer to resolve a past injustice by bringing its perpetrators before the law but to work through history in order to predict the injustices of the future. By the 1970s, Pynchon argues, this figure has become a conspiracy theorist, and the conspiracy that he uncovers provides a highly compelling origin myth of the present.

Heitzler’s attraction to the postwar culture of the Pacific Palisades speaks to this as well, and his evocation of the conspiracy is no less tinged with the cozy autumnal hues of fond memories. For the audience in turn—at least for those who came of age before the emergence of the World Wide Web—the pleasures it offers are familiar ones. If we return again and again to this place, it is because we obviously enjoy the vertigo of teetering there on the edge of a narrative that thereafter becomes literally unreadable. Who would not prefer to tap a succinct three-way telephone conversation between Adorno, Mann, and Schoenberg, for instance, than to confront an endless stream of wiki-leaks? The new epic author is perhaps a big-data miner like Edward Snowden, and the new epic work, a big-data dump. No more paranoid projection is required to produce this conspiracy; everyone knows it actually exists and, moreover, that we all already play a part in it. The dedication that opens the Pacific Palisades book reads: “for paranoia.” Considering all that has transpired since the histories compiled in its pages, the fact that our present age could be described as post-paranoid is perhaps astonishing, but Heitzler’s work reminds us that this too could have been predicted as we began winding our way from high atop the Pacific Palisades down to the flats.

Jan Tumlir is an art writer who lives in Los Angeles. He is a founding and contributing editor of X-TRA.