A rewarding experience for me is a narrative structure where you are not told what to think and what to do. Otherwise, that’s what you get in jail. That’s what you get with government. And when you get it in art, it can put you to sleep.1

–Bruce Conner

Bruce Conner, Opening sequence of A MOVIE (details from filmstrip), 1958. 16mm film, black and white, sound, 12 min. Courtesy the Conner Family Trust.

Bruce Conner was born in 1933 and reportedly died multiple times. He fabricated false accounts of his own death to rid himself of a standard, predictable biography. This strategy began in 1959 with a stark black and white invitation announcing his exhibition entitled WORKS by the late BRUCE CONNER.2 In the years following, he continued to generate false reports about his death. After a request for information from Who’s Who in America, Conner wrote back declaring his death. As a result, he then appeared in the 1973 issue of Who Was Who in America. Conner eluded the restrictions of identity and authorship in his life through this conceptual gesture and via strategies of avoidance, confusion, and the use of aliases. Almost 50 years after his first disappearing act, Conner passed away in the summer of 2008. His ultimate end is an apt occasion to recognize the power of absence within his career, whether symbolic or literal.

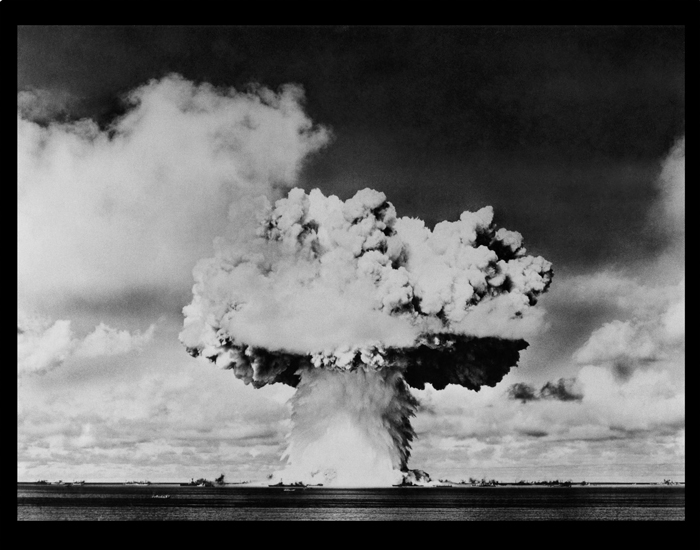

The end was the beginning of Bruce Conner’s film career. His first film, A MOVIE (1958), starts with appropriated leader countdown, a woman undressing between the numbers 3 and 4, and an image declaring the end. The film then quickly fires through a montage of random found footage: cowboys chase Indians, an elephant runs towards the camera, and a locomotive screeches across the screen. Each scene of movement plays for several seconds and then ends with a stark black screen. The film’s visual barrage continues with title screens and narratives that enter just as quickly as they exit: race cars take off, the end appears again as a momentary disruption, an atomic bomb goes off, movie credits are reintroduced several times and crashes ensue. Eschewing a clear linear narrative, time lapses at an inhuman rate and disparate scenes appear within a haphazard timeline. A MOVIE was the beginning of Conner’s false ends and he never looked back.

Deeply invested in subversions, Conner spliced together signifiers to create irregular timelines in many artistic forms. The bold title of his 1999 survey exhibition at the Walker Art Center, 2000 BC: THE BRUCE CONNER STORY PART II, promised an epic tale. However, Conner’s stories are never direct. In this case, the very title is a combination of temporal signifiers. The travelling exhibition took place in the years 1999 and 2000 AD, but 2000 was incorporated into the title along with the abbreviation of BC (also Conner’s initials). In addition, no clues were given about the nonexistent PART I. Through the absence of a PART I and PART III, Conner’s title is a disembodied signifier. Unlike WORKS by the late BRUCE CONNER, this title does not refer to death, but rather signifies a new, artificial timeline.

Just as one experiences a “birth” of a moving image, single frames disappear within the overall temporal structure of a single film. Within a traditional film, the forward mechanical movement of the medium parallels the progression of the narrative. Time passes in a logical order with a strict beginning and end caused by the movement of the film itself. Hollywood stories similarly continue in a linear fashion, often with an end denoted by a death or a villain’s defeat. The stillness of film, which acts as a bookend to the story, may then imply a sense of death because it concludes this narrative progression. As film theorist Laura Mulvey suggests, “Of all the means of achieving narrative stasis, death has a particular tautological appeal, a doubling of structure and content.”3 Throughout his career, Conner used breaks in film narratives and their structures to cause temporary departures from linear movement, thereby departing from an expected and continuous timeline.

For A MOVIE, Bruce Conner chose to tie his disparate imagery together with a montage of quick jump cuts. Conner used a constant of black and white film to make these leaps of time, space, and subject matter as seamless as possible By quickly moving from one scene to another (at times in less than a second), Conner’s images provide an overwhelming flurry of movement evident to the viewer. As a result a viewer’s eye does not disconnect the scenes from one edit to another, but instead sees a hurried interconnection of multiple movements. The extreme edits reject standard storytelling techniques. In fact, Conner defies standard time within A MOVIE by starting with the end title screen, repeating black still frames, and breaking apart the film’s continuity. The scenes of A MOVIE continue to flash so quickly in front of a viewer’s eyes that some may need to look away because their vision is overwhelmed by the montage of moving imagery. The structure of time within A MOVIE does not move in a horizontal fashion like a train, but rather transports a viewer from one frame of reference to the next through his techniques of rapid-fire film editing.

By using hand-cut splices of 16mm film, Conner created a montage of disembodied scenes that occur in a new time independent of their original narratives. He selected footage from B-movies and newsreels purchased from a camera store including propaganda films, racing shorts, westerns, and other found material. The resulting images build upon one another into a cacophony of popular cultural and war time symbolism. While disaster is not limited to modern military battles, the film is filled with Cold War fears of technology: race car drivers skid off their track, a submarine launches a missile, and a suspension bridge collapses. Laura Mulvey’s observation of the recurrent theme of death again continues through the recurring explosions and crashes of this film. Echoing the structure of time in the film, each scene is a new beginning but ends as abruptly with a disaster. Unlike a direct narrative, the visual barrage of A MOVIE teases false ends and new beginnings through impossible and shuffled sequences.

Bruce Conner, Opening images of REPORT, 1963-67, 16mm, black and white, sound, 13 min. Courtesy the Conner Family Trust.

Through jump-cuts in REPORT (1963-67), Conner again denied the normal linear motion of time. He collaged archival footage of John F. Kennedy’s fatal motorcade ride with sequences of found film and countdown leader. Repeated over and over in the opening sequences, Conner shows the same image of the President’s car proceeding down the parade. The screen suddenly goes black and tension builds through a panicked voice on the sound track. In place of the actual assassination footage, Conner imposes alternating frames of pure black and white frames, film leader, and text. The visual effect created by the film media denies a normal linear motion of time and a viewer cannot anticipate the next sequence of events. This intensely optical section of the film, which replaces the historic scene of JFK’s assassination, hovers without narrative and suggests an allegorical response to the unknown experience of death. The shocking footage of the assassination that Conner leaves out has been seen many times by most Americans. Displacing the familiar scene may be his way of avoiding the event or reflecting upon a national trauma in a Freudian manner. While unseen, the implied end sends a chill into the audience as they recall the images of the shooting and the President’s death. Unlike the stillness associated with death, REPORT includes aggressive flickering to suspend time. The images within this abstract interlude typically characterize the beginning or end of a traditional film structure. However, REPORT then proceeds into an epilogue featuring a “re-birth” through JFK’s inauguration speech and collaged images of pop culture. With structural and narrative alterations, Conner halts linear movement of time with flashing visual effects and then continues to reintroduce Kennedy’s myth.

Conner’s own biographical timeline was just as flexible with moments of stasis and temporal changes. At the young age of eleven, he reportedly felt the effects of aging through an indescribable vision. He relaxed on a rug and drifted into a state of unconsciousness. He suddenly felt ancient, but also knew he did not leap forward in time. The only way he could describe it was by saying: “There were so many things that were unknown secrets, that adult society knew, that they didn’t let children know about. I thought this was one of them.”4 If this is truly the case, Conner’s consciousness of the sequence of his life’s events may have been hardwired differently than others. A person is expected to grow old at a particular rate of time; however, through this story Conner suggests that his consciousness aged quickly while his body did not change.

Bruce Conner, CROSSROADS, 1976. 35mm film, black and white, sound, 36 min. Courtesy the Conner Family Trust.

Stillness and the absence of narrative was also used in Conner’s film CROSSROADS (1976), a rumination on the atomic explosion at Bikini Atoll. The explosion is repeated twenty-seven times within the film with footage recorded by the U.S. government from numerous camera positions. The actual detonation of the bomb lasted moments, but Conner expands it into a thirty-six minute film replaying the destructive video in normal and super slow motion. The still shots, some of which are longer than Conner’s earliest films in their entirety, add to the haunting quality of the image. Additionally, he altered the duration of the explosion through the soundtrack, created by Patrick Gleeson and Terry Riley, which emulates the sounds of an explosion while the bomb image remains unnaturally still. Through these manipulations, the film structure recalls a motionless photograph, while its subject is one of great kinetic energy.

The film’s central image of the atomic cloud is an eerie symbol of death. CROSSROADS is a repetition of the distressing image without a surrounding narrative. With the fears of a world torn asunder from atomic explosions, and the extreme after-effects of radiation, could this scene be less than traumatic for an audience in the 1970s or during the Cold War? Much like REPORT, Conner repeats scenes without showing the climax of the actual event. In CROSSROADS, Conner slowly reveals the explosion from multiple angles but does not depict the full dynamic potential of the bomb. He provides an image of maximum destruction, but denies its full potential.

The absence of the actual explosion in CROSSROADS and lack of representation of JFK’s death in REPORT recall the many disappearances made by Conner himself. In the 2000 BC catalog, Joan Rothfuss used the label “Escape Artist” to describe Conner’s habits of avoiding public appearances.5 Conner seemed to disappear many times during his career, including a period between the mid-1950s to 1964 in which he was not photographed. In addition, he did not sign his work for several years in the 1960s—which included the lack of his name on the title screen of his film COSMIC RAY (1961). Besides complete disappearance, Conner also used repetition to hide or divert the authorial presence behind his work. After finding many others with his name, he proposed, but never realized, a Bruce Conner Convention. Conner created two different buttons for this event, which respectively said “I am Bruce Conner” and “I am not Bruce Conner.” This doubling continued in 1971 as Conner titled his solo exhibition THE DENNIS HOPPER ONE MAN SHOW. Crediting the authorship of his etchings to his friend Dennis Hopper, Conner allowed his personal identity to disappear.

Conner used manipulations of structure and narrative to create an enigmatic sense of time in his films and career alike. His lifetime is now officially recorded as 1933 to 2008, but the Bruce Conner story continues to drive forward. Much like the many stops and starts within Conner’s films, the end is still elusive. Using methods of disappearance and absence, Conner abandoned predictable conventions to cleverly side-step easy categorization as an artist. His work will continue to be ripe for rediscovery because there is still much to be uncovered within his complex, unpredictable narrative.

John McKinnon, Assistant Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Milwaukee Art Museum, is currently working on a posthumous exhibition of Bruce Conner’s work.