Note 1

“A divine teleology secures the political economy of the fine arts.”

-Jacques Derrida

“The tendency has always been strong to believe that whatever received a name must be an entity or being, having an independent existence of its own. And if no entity answering to the name could be found, men did not for that reason suppose that none existed, but imagined that it was something particularly abstruse and mysterious.”

-John Stuart Mill

“The inner and the outer did not form a harmonious unity, for the outer was in opposition to the inner, and only through a refracted angle is he [Plato / Socrates] to be apprehended.”

-Søren Kirkegaard

“I can’t help fooling around with our irrefutable certainties.”

-M. C. Escher

It is of the utmost urgency today to fundamentally transform the contemporary discourse on religion by radically transforming the very terms of that discourse (and its “irrefutable certainties”). Religiosities and their antitheses were twins at birth. Instead, I will take my task here to be not a “criticism” of religion, but rather a critique with respect to religion and religiosities. By the term critique I mean not simply examining the flaws or imperfections of a doctrine or a particular religion, or of religion as such (given the dangers of using a very specifically Eurocentric term such as “religion” in the first place). Critique is not a series of criticisms designed to “improve” a religion but is rather an analysis focusing upon the grounds for a system’s possibility, reading backwards from what is claimed to be natural, obvious, or self-evident. The aim of critique is essentially the work of philosophy: not only to articulate the historicality and artifice of naturalness, but also to make clear how such artifice is commonly blind to itself.2

My aim here is not simply to make religion “better” in favor of a “kinder, gentler theology” free of endorsing or promoting the death of adherents of different faith systems or different sectarian versions of one’s own faith, though surely that is to be desired by all. Instead, critique is concerned with the deconstruction and exposure from within of what a system’s basic presuppositions conceal–the blind spots and amnesia about what produces and maintains a system or systems of religiosity in the first place. Critique is more concerned with establishing primarily what a statement or claim or where it derives from and secondarily with what that statement purportedly “means.”

Critique, then, is a certain strategy of reading—a method of very closely and carefully reading statements, claims, theories, and beliefs—foregrounding not the weaknesses or stupidity or absurdity of a religious doctrine or dogma but rather foregrounding a belief’s structurally necessary silencing of what gives the belief its apparent naturalness or cogency. As a strategy of close and attentive reading, critique is a “deconstruction of the validity of the commonsense perception of [what is unquestioningly taken to be] obvious.”3 (In which case, then, it is a sibling of religious exegesis itself: a romance, perhaps, of twins separated at birth.)

My paper, then, attempts to elaborate a critique of religiosity in foregrounding what many religiosities appear to conceal or are ambivalent about, as a small contribution to elaborating a fundamental shift in perspective on the nature and role of religious systems in contemporary life. I will be using the term religiosity to foreground the structural processes or behaviors common to many instituted religious systems, focusing upon what I will call the epistemological technologies of those systems: how they work as intellectual, aesthetic, and ideological practices. My motivation for elaborating such a critique is in response to the urgent need to address the increasingly catastrophic problem that religiosities are claimed to have become in our world: the massive release, as the philosopher Alain Badiou recently put it, of ancient irrational passions which in the overt or covert name of one or another sectarian belief system have unleashed, in so many communities and nations, what must of course be absolutely unacceptable: an escalation of death and destruction in the name (literally or covertly) of religion. The problem with religion is larger and deeper than religion but concerns religiosity, of which established religion is in fact but one symptom–one symptom amongst others. My concern, then, is not with criticizing religion, but in understanding what processes religious systems are an effect and product of.

I should begin with a word about my own position. I see myself as standing both inside and outside a number of conventional academic fields of study, as my work occupies–to use an architectural metaphor–the grout” or cement filling between the “bricks” of several instituted areas of inquiry. My professional training and experience are, in a sense, elsewhere. So it is from elsewhere” (or perhaps several elsewheres) that I am writing. what follows is a deconstructive reading of some fundamental conundrums in religiosity and in artistry, and my paper will constitute a series of provocations for discussion. Such questions are themselves of very great antiquity in the western tradition–a situation that problematizes any claim that a criticism of religion in relation to artifice and artistry is a recent “modern” phenomenon.

A contemporary critique of these issues is necessarily complementary to what religiosities (and artistries) mask, refuse, deny, or repress, namely their own ghosts or hidden and contrary suppositions. of course any provocation is part and parcel of what it ostensibly provokes, so perhaps all I mean to signal by these preliminary observations is a certain topological mode or method of reading. I have tried to highlight several of the most pressing dilemmas common to reli- giosities of various different kinds, and I’ve condensed my observations into a few basic theses, theses intended quite explicitly as provocations to discussion.

First Thesis (First Provocation)

All modes of religiosity may be distinguished by being either ambivalent, amnesiac, or duplicitous with respect to the fabricatedness of their own fabrication; their own artifice or artistry.

There are a number of implications or corollaries that appear to follow from this, chief among them being:

a. Religiosities are responses to circumstances perceived as prior or pre-existing or determinant: as the products or effects of some condition or experience.

b. Religiosities are subsequent to and presuppose or “art”religion is an artistic or aesthetic practice) which suggests further that

c. Artistry and religiosity are either alternative responsesto some common or determining condition or alternative ambivalences or amnesias with respect to some prior problem or circumstance.

Religiosity and artistry may thus be seen either as different points on the same continuum rather than points in different conceptual spaces, or as indeterminate or circumstantial and situational products and effects of each other, or both. Some of these corollaries will be examined in some detail as we proceed.

Second Thesis (also concerning the epistemological status of religiosities) Religiosities are fundamentally invested in the problematic of representation to the extent that they constitute positions taken with respect to what might be called the rhetoric, syntax, or semiology of signification: the nature of the relationships (structural and ethical) between an object or event and its assumed cause: the nature, so to speak of what it means to “witness.”

In the case of most religious traditions, and especially of the various alternative monotheistic religiosities, this has normally entailed a declaration of an ontological dualism, and in particular a posited opposition between what might be termed “materiality” and “immateriality.” The positing of a dualistic ontology whereby a “material” world is contrasted with an “immaterial” or “spiritual” and “transcendent” world is not, however, an opposition between two equal states or modes of being, but is rather marked by a hierarchy of value, whereby one realm–the spiritual or immaterial is (normally unquestionably) taken as transcendent and primary, or even as the origin or cause of the world of materiality. The material world is seen as the product and effect of transcendent, immaterial forces. The “material/immaterial” dualism is of course not neutral but is already articulated from the rhetorical perspective of religious faith-systems themselves– a function of religionist categories.

Commonly this realm of the immaterial is personified or reified as an immaterial force, spirit, soul, or divinity,

in which (or in whom) is invested transcendent and usually unlimited, immortal, or permanently enduring or recurring powers or abilities. These latter are often invested with interventional force, with a power to intervene in and affect aspects or properties or qualities in and of the (produced) “material” or secondary world. Conversely, such reified principles or powers are often also understood to be impossibly remote, unapproachable, or even indefinably and totally other. But both conditions or properties of the immaterial principle or “spirit” are co-determined and co-constructed, and in some religious traditions oscillate and alternate: a double-bind of absolute otherness versus transcendently powerful interventionism. Any concept of an immaterial spirit or god as totally unfathomable otherness is linked and defined by an opposite complete transparency. Sometimes the god hears one’s wishes, sometimes it doesn’t.

What is traditionally masked in (or by) such ontologies are both their hierarchical structure or systematicity and their articulation as a religiosity; the very opposition between a “material” and an “immaterial” level of existence is defined from the position of that which it presumes (pretends) to investigate. The material/immaterial ontology is not a conclusion but a preliminary philosophical hypothesis masquerading as that which it ostensibly seeks to prove. Simply by evoking the “materiality” of the world, that the world is characterized by a property of materiality or of matter, it simultaneously co-produces its ostensible antithesis: the “spiritual” or non- (pre- or post-) material world. To criticize “materialism” is to create and invoke its alleged opposite.

This thesis suggests the following corollaries:

a. The material/immaterial opposition is the ground or template ormatrix for positing equivalent or complementary properties in multiple dimensions: on the level of the scale of the individual, the group, the community, the nation, the species, and so forth.

b. These scalar transpositions or postulates are as (metaphorical) equivalences, which commonly specify a certain appropriateness: certain proper or fitting human (and other) behaviors which bear with them legal or ethical force or discipline.

To which may be added that the effect of the maintenance of this duality is the possibility of imagining the belief that the “immaterial” has an “independent” existence of its own (a “transcendental signified” exceeding the chain of material signs), and thus prior to its “material” antithesis, constituting the essence of religiosity.4 This semiological or epistemological artifact is the most important and powerful implication of religiosity. But it simultaneously makes possible the imagining of its antithesis, namely that: the “material” has an independent existence of its own, independent of and prior to any imaginary projected “immaterial” antithesis, which constitutes the essence of artistry or artifice.

All of which suggests a further conclusion, namely that the maintenance of the duality generates an uncannily “oscillating ontology,” whereby “materialism” and “spiritualism” (to use the most common terms) perpetually contend for a position of primacy or transcendence. The entire “contest” between spiritualism and materialism is a rhetorical illusion.

In general, then, the maintenance of the materialism/immaterialism dualism–the belief in a realm of spirit or immateriality and its (from certain religious perspectives) lower or “derivative” antithesis, a realm of “pure” (or mere) matter–or vice-versa– allows for the possibility of each perspective imagining its antithesis. Each is the ghost perpetually haunting the “body” of the other: the system of its otherness. Each “realm” or mode of being is essentially unstable or fragile, as its essence always contains its “opposite,” each opposite (each “elsewhere”) being what grounds and makes possible the first ontological realm.

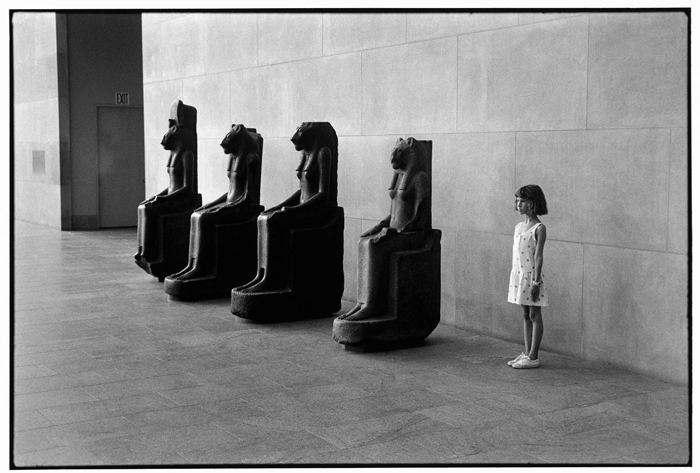

This was precisely the problem investigated 2500 years ago by one of the most ancient treatises on artifice, Plato’s Republic, which famously (or notoriously) called for the banishment of the mimetic arts from an ideal city-state (polis), an issue which also underlies the subsequent ambivalence and/or antipathy of religiosities toward artistry or artifice. Strictures against mimetic artifice, whether in terms of “naturalistic” imagery in some or all civic contexts, such as the portrayal of a reified immaterial force or divinity or even of that force’s proponent, inventor, spokesperson, “saint,” or “prophet,” or against the complete visual “representation” (writing) of the name of a reified immaterial force, have been essential (even if ambivalently enforced) features of all monotheistic religiosities.

Perhaps the extraordinary fear–the terror endemic to monotheistic religiosities in the face of possible “disobedience” (with respect to “visual representation”) –more often than not leading to ostracism, corporeal punishment, or at times in all ultra-orthodoxies or fundamentalisms violent death, is a perfectly “logical” and consistent application of a systemic need to forestall or prevent even the imagining of difference. By this I mean that if it were to be admitted that, for example, the structure of a certain social, political, or economic system were an artifact of human artistry (rather than having been “pre-ordained” by a reified immaterial force or divinity or deified ancestors, or by “natural” law), it would allow for the possibility of thinking otherwise–of imagining other forms of community, organizations of cities, economic systems or ways of life, even of different forms of human society: different ways of being “human.” This is the essence of Plato’s prescriptions for an ideal city-state (polis),5 which in the terms I am using here, resulted in what can be called a political religiosity– itself a central foundation of Augustine’s distinction, many centuries later, between an ideal “City of god” and a “City of Man.”

The terror at the heart of many religiosities attests to the fundamental fragility of instituted and enforced systems of thought (established “religions” in a strict sense) in the face of possible evidence of alternative “realities.” If a faith community’s members might be exposed to the awareness of the artifice of its religiosity–the possibility of it being not “created” by an immaterial (and thus unassailable) source or force but rather has its origins or sources in (“mortal”) human invention–then the possibility also exists that other realities, beliefs, social systems, cosmologies, reified immaterial forces (gods), or even ideas of what is “properly” “human,” might be imagined with equal cogency. The dreaded result would be the patent “destabilizing” of a given community or social contract, and the loosening of its legal bonds, leading to a vision of chaos. The reality or the very cohesion of an entire universe “really” does hinge on the size of a bikini. what if the land your people now occupy really wasn’t the gift of an immaterial divinity but was actually stolen by you or your ancestors from others?

This antithesis to fundamentalist religiosity is what some have characterized as a “postmodern condition,” although it would have to be said that any such “condition” is in fact a property of the orthodox system itself (for example, a “modernity”) being threatened: its co-produced and co-determined Other, which inhabits the system as its very possibility of existence in the first place.6

Religiosity would then appear dangerously fragile at every point in its system, if it can be cosmologically threatened if ten centimeters of female flesh were exposed, or if the flesh of an improperly slaughtered animal is served at a dinner table, or if the consequence of enjoying sex “outside” a “marital” state is being stoned or burnt to death, or if the utterance of a disrespectful or even incorrectly pronounced or written word in connection with a sanctified or hallowed person or divinity, could instantly incur the wrath of that divinity or prophet or minister, or if being of a different religiosity or ethnicity than that of someone in power could legally expose one to rape, impoverishment, or death. Ironically, what is specifically evoked in such instances of terror is the threat to the propriety or decorum of a social or civic order or code of behavior–in other words, the stylistic consistency and aesthetic harmony of an artistic fabrication. The “truth” of any religion is a property of its artistry. Such ironies, as Kierkegaard and his philosophical tradition of post-Hegelianism clearly understood in the late 19th century, are not “merely rhetorical” but are in fact deeply structural–which is to say ethical, suggesting the mutual entailment of aesthetics and ethics; more on this later.

Third Thesis (The mutually knotted [chiasmatic] entailment of the critiques)

An effective critique of religiosity will be linked to an effective critique of art, artistry, or artifice, which in its own right constitutes a perspective or position taken with respect to signification and representation which is ostensibly antithetical to that of religiosity.

Among the principal corollaries of this thesis are:

a. Art (in the modernist sense of “fine art”) is a secondary effect of a position taken with respect to the of representation; there is no art as such except as a reified (sanctified) modernist commodity;

b. Art is not a what (a kind of thing) but a when a position or perspective on things) whose reification constitutes an idolatry of a certain religious or spiritualist ontology, with scalar or dimensional consequences (the “artist” (genius) as a metaphor of a “divine” creator or artificer, and so forth);

c. The modern discourse on (fine) art, which is distributed across a network of discursive practices (art history, art criticism, art theory, aesthetic philosophy, and a variety of related modern disciplines and industries tourism, heritage, fashion, etc.) comprises a secular religiosity legitimizing a multidimensional coordination of social behaviors in connection with the evolution and maintenance of the modern nation-state. Art, in short, is the obverse of religion in the ostensification of its fabricatedness.

The point of these theses or provocations is to open up the discourse and critique of religiosity as essentially connected to and simultaneously an effect and artifact of the perspective on signification and representation (and of an ethics of the relations between subjects and between subjects and objects) of that which it denies–the discourse on and of art, artistry, and artifice. Art and religion are fundamentally interdependent upon each other and mutually defining, and the critique of either remains superficial and incomplete apart from or in the absence of a coordination with the critique of the other. But the point is that there are not, strictly speaking, “others,” as if these (religion and art) were two autonomous and distinct entities rather than being facets and products of a common underlying philosophical problem.

Far from being distinct or opposed domains of knowledge-production or behavior, artistry and religiosity rather constitute epistemological technologies which are the products of different perspectives on (and alternative responses to) a common, fundamental cognitive problem–the problem of representation (and the topology of relations between subjects and objects) as such. Art and religion are opposed yet mutually-defining

and co-determined answers or approaches to the same question of the ethics of the practice of the self,of how self-other relations are to be coordinated. The relationships between art and religion are not relationships between two random or incidental cultural phenomena; the problem of that relationship is precisely what defines and determines our most fundamental understanding of each. It is in that relationship–how religions deal with and make possible art and artifice, and how artifice simultaneously deals with, produces, and makes possible religiosity in the first place–that the essence of each can be articulated and understood. Note, however, that by saying “each,” one already reifies each perspective on signification–which in fact is my more general point: neither art nor religion exist except as reifications of perspectives or positions taken on a common, more fundamental philosophical ontological phenomenon: the nature of the relationship between entities and, ultimately, the question of otherness in its co-construction of sameness.

Fourth Thesis

All the relationships considered in the first three theses constitute alternative ethical positions or implications for individual or collective behavior, as ethics is itself a consciousness of the nature of relationships (of any kind) as such: a topology of self and other (implying a substantive rethinking of what is meant by ethics).

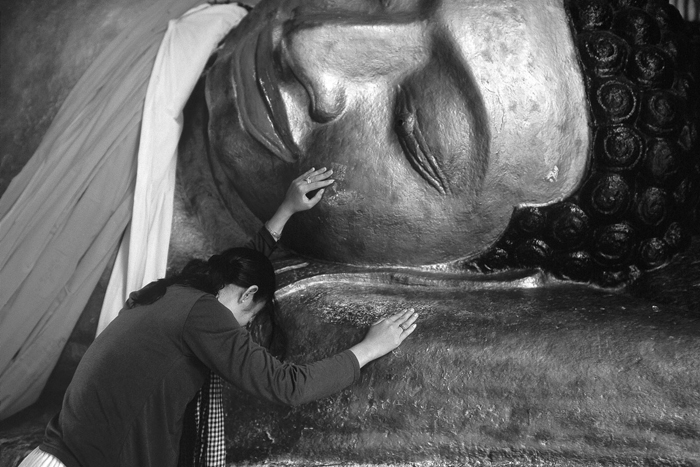

The entailment of ethics and aesthetics (artistry) has had a number of consequences in legitimizing modern disciplines or institutions such as art history,7aesthetic philosophy, established religion, and the political economies of modernity, which concern the virtual “superimposition” of objects and subjects wherein the object is seen by a subject through the screen of an erotic fetishization of another subject. The object–and in particular the (modernist) “artwork”–is invested with erotic agency (every object a potential love-object) and deployed as an object of sublimated erotic desire. Aesthetics (and fine art) are historically entailed with an ethics of what (from the perspective of religiosity) is framed as idolatry and fetishism, a situation (as seen in the image of St. Teresa by Bernini) where in certain religious traditions, artistry and religiosity are held in uneasy balance, recalling that of an optical illusion, perpetually oscillating between alternative geometries, alternative realities.

It is time to begin, not “conclude,” because these are essentially open-ended debates. The most basic question around which both art and religion revolve is what an object or entity may be said to be a witness to–precisely the core of the issue addressed by Plato, and which still determines and generates debates about idolatry, fetishism, and blasphemy today, 2500 years later. But witnessing does not exist as an abstraction, apart from specific, historically active producers, objects, users or audiences; witnessing is always a complex triangulation of semiotic perspectives.

So we must be very clear about what grounds and makes possible all current religious debates in the first place–their completely simultaneous aesthetic and philosophical presuppositions and beliefs, which were prefigured in the philosophical controversies such as that exemplified in Plato’s discussion about what constituted an ideal community or city-state.

I will end with a very brief coda–a look at a remarkable critique of Kant’s Critique of Judgment (Kritik der Urteilskraft)8 from a 1975 essay by Jacques Derrida entitled “Economimesis,” published shortly before his more well-known volume La Verite en peinture (The Truth in Painting).9 In that essay he noted that “[A] divine teleology secures the political economy of the fine arts.”10

I have in effect argued here that Derrida’s comment is only half the story and needs to be balanced with its complement: that at the same time it is “Artistry that secures the political economy of religion.” Derrida’s remark referred to Kant’s perspective on aesthetic practice in his Critique as arguing for a (very Platonic) co-ordination of artistry and religiosity. In observing that even though in dealing with a product of fine art, Kant says one, “must become conscious that it is art rather than nature, and yet the purposiveness in its form [what Aristotle would have considered its “entelechy”] must seem as free of all constraint of chosen rules as if it were a product of mere nature.”11

In other words, the artist (as a figure of genius) is imagined as producing in artistic practice a simulacrum or exemplar of “divine” agency; an analogue to the way in which a reified immaterial force (a “god”) is imagined to “design” and “produce” nature itself (the material world as if it were a “creation,” a work of art[ifice])a work of “intelligent design.” Kant’s perspective on aesthetics builds upon many centuries of elaborations on the proper ways in which artistry and religiosity might serve each other, a debate as old as Plato and Aristotle, not only antedating by centuries the historical invention of post-tribal monotheisms such as Christianity or Islam, but constituting the core problematic of each such tradition.

Art for Kant shouldn’t simply re-produce or re-present nature. Ideally (for Kant is concerned with what constitutes the “fine arts” rather than what I’ve been concerned with here, namely artistry or artifice as such), art must produce like nature (and by implication, like nature’s “god”)– precisely the question opened up by Kierkegaard. The world of artifice is not a “second world” alongside the world in which we live; it is precisely the world in which we really do live. The human world is a world of art: presentation rather than imitation or re-presentation. Derrida’s point was that (in Kant) the realm of the aesthetic was naturalized and given point and direction– was purposeful or entelechal–insofar as it could be analogized to a “divine teleology” or purposiveness. More generally, then, the modern invention of what is commonly taken as constituting art is “secured” (socially legitimized) by being imagined as an analogue to divine creativity. In such an ideological framework, the “artist” (that other modernist fabrication or invention) is a micro-dimensional projection of a divine persona (“genius” in its most common rhetorical rubric). The “artist,” the (romantic) idea of the artist-genius, was and is the device that pins together artistry and religiosity: the “hinge” linking aesthetics and religion. This resonates with the social and ethical position of artist or artistry in many cultural traditions; artistry creating and defining the sacred itself, and erasing the traces of its own artistry; sanctity’s dependence upon the erasure of its artistry or fabricatedness.

In modernity, and especially with Kant and his philosophical tradition, including that of aesthetic philosophy and its concomitant network of discourses and practices (art history, art criticism, etc.) art came to be socially sanctioned through the analogue of the “soul,” the genius, wisdom, and “spirit” of the artist, which (if exercised with a certain propriety or decorum) might truly “magnify the Lord” even where it seems to merely magnify its own ego: romanticism as a “secular” religiosity. The entire modernist discourse of the fine arts can be seen as a secular theologism or a theology of the political ethics of the self in the service of the modern nation-state.

My paper is entitled “Enchanted Credulities” so as to highlight the uncannily comparable enchantments attending the fabrications of both religiosity and artistry religion as an art and art as a religion: projections of possible worlds which simultaneously acknowledge and deny their fabricatedness. what you’ve read are a series of openings in an ongoing critical engagement with some very ancient yet enduringly complex questions. These are problems and conundrums that remain unresolved in many contemporary discussions and debates, and which antedate what we understand as either “religion” or “art” today.

Donald Preziosi is a member of the History Faculty at the University of Oxford and emeritus professor of Art History and Critical Theory at UCLA. His current book project examines the antithetical relations of artistry and religiosity.