In 1992, the year the artist David Wojnarowicz died of AIDS, the New York City Planning Department released a comprehensive redevelopment proposal for the city’s waterfront. Subtitled Reclaiming the City’s Edge, the 18-year plan anticipated the transformation of Lower Manhattan’s shoreline from a derelict post-industrial zone into the recreational and tourist attraction that it has become, with popular sites such as Diller, Scofidio + Renfro’s High Line and, more recently, the new Whitney Museum of American Art, where History Keeps Me Awake at Night, the first major retrospective of Wojnarowicz’s work in nearly two decades, took place.

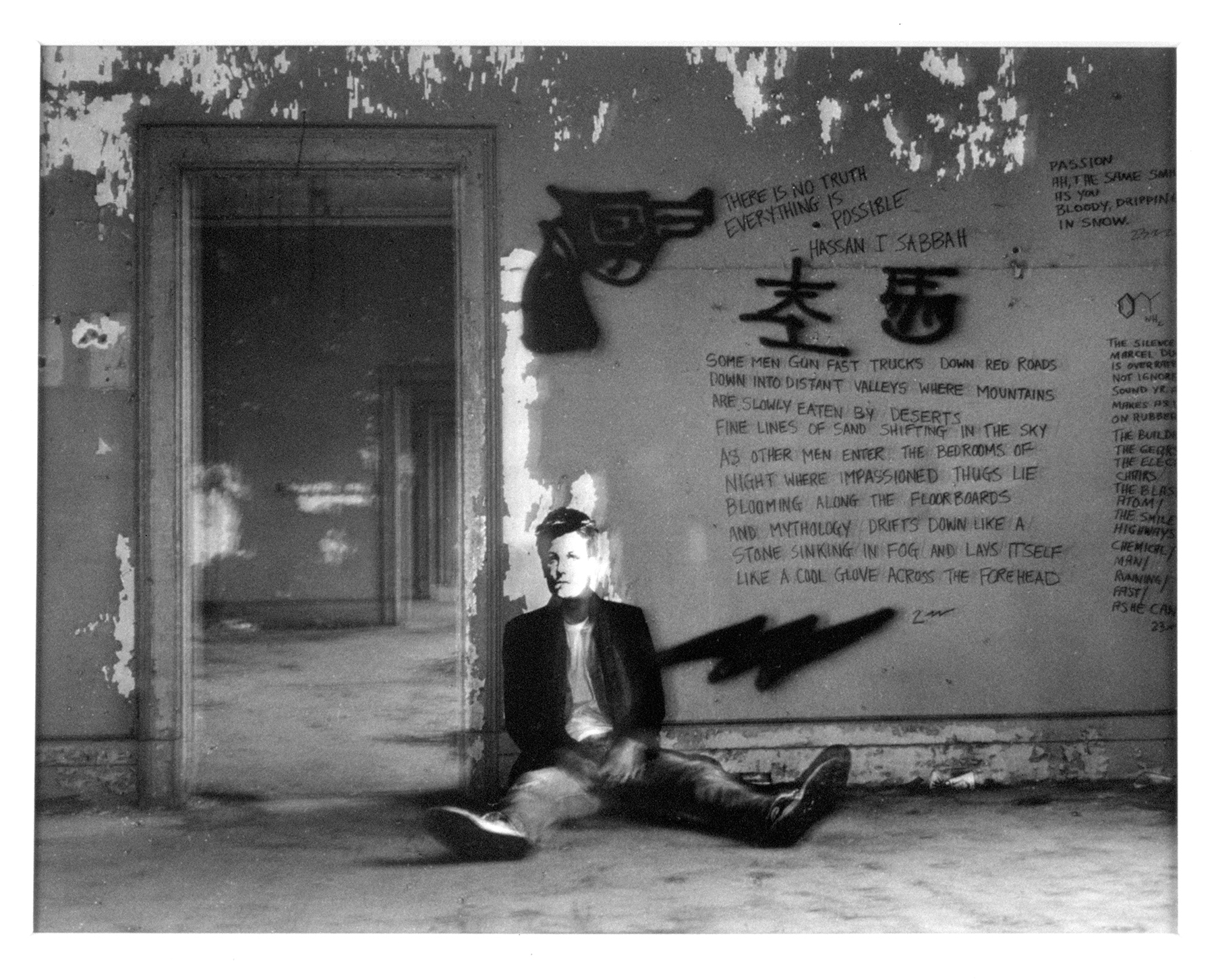

Andreas Sterzing, David Wojnarowicz and Mike Bidlo at Pier 34, New York, 1983. © Andreas Sterzing. Courtesy of the artist and P•P•O•W, New York.

The “reclaiming” part of the plan wasn’t a metaphor. Since the sixties, New York had disavowed much of its waterfront after the heart of its shipping industry moved across the river to New Jersey. Many of the city’s piers and their grand Beaux-Arts terminals, constructed at the turn of the century, were left to rot. Subsequently, these were commandeered by artists such as Vito Acconci, who held a month-long, midnight confessional at the terminus of one deserted Westside pier, promising to reveal dark secrets to anyone that visited him. Joan Jonas used the rubble of the shoreline as a stage for her performance Delay Delay (1972). And Gordon Matta-Clark cut towering slits into the floor, wall, and roof of the terminal of Pier 52, near the current Whitney. The notorious Christopher Street pier and others were also vital cruising zones, as well as places for gay men to sunbathe and hang out. In one sense, the abandoned piers embodied the city’s mismanagement: its near bankruptcy in 1975, the failure of urban renewal, and the loss of thousands of local jobs. From another perspective, however, their ruin presented a thrilling opportunity.

The autonomy of the piers was particularly formative for Wojnarowicz. In his incandescent memoir, Close to the Knives (1991), he captures his fascination with the waterfront as a site of both public art and public sex, alighting first on “vagrant frescoes painted with rough hands on the peeling walls, huge murals of nude men…with large outlined erections poised for penetration.” In the next paragraph, he witnesses the “pale flesh of the frescoes come to life” as men “line the walls like figurines before firing squads.” 1

David Wojnarowicz, Arthur Rimbaud in New York (sitting/pier, gun), 1978–79/2004. Gelatin silver print, 14 x 11 in. 1 AP. (WOJ-E202). © Estate of David Wojnarowicz. Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York.

Wojnarowicz began frequenting the piers in 1979, when he was in his mid-twenties. The same year, he featured them in one of his first and most well-known artworks, Rimbaud in New York (1978–79). In this series of black-and-white photographs, friends of the artist don a photocopied mask of Arthur Rimbaud. An exceptional writer himself, Wojnarowicz not only considered the French poet a literary hero, but also a kindred figure of social alienation. The work conveys this position of apartness; it exists somewhere between a document of a performance and an in-camera collage, thrusting a quintessential image of Rimbaud against the contemporary city. A proxy for the artist, Wojnarowicz’s Rimbaud visits the amusement park at Coney Island, the 8th Avenue subway, a diner with a neon-lit pie case, and the marquees of Times Square. But the play of anachronism is more amorphous in the pictures staged at the piers. Aside from Wojnarowicz’s graffiti guns and poetic asides scrawled on the walls, the setting—a vast mirror-maze of empty rooms and tattered wooden floors—seems to come directly from the time of Rimbaud.

During the early eighties, Wojnarowicz and a group of around 30 other artists, including the painter Mike Bidlo, established a consistent presence at Pier 34, at the end of Canal Street, reclaiming the shipping terminal as a community studio and improvised exhibition space. In Wojnarowicz’s show at the Whitney, a slideshow by photojournalist Andreas Sterzing documents the group’s spirited output, little of which remains. In the pictures, the terminal’s cavernous space is open to the elements: water, snow, and detritus gather on the floors, while the walls and windows are painted with kinetic human figures, a border of creeping rats, ominous political proclamations, and Wojnarowicz’s renderings of a choking cow and a pterodactyl spreading its wings in a corner. In a statement Wojnarowicz and Bidlo circulated at the time, the pair wrote of the creative energy inherent in empty buildings. What they had done, they said, was possible everywhere.

But standing in the Whitney, just steps from where they were, the potential of the piers now seems remote. This irony—noted by numerous reviewers but ignored by the museum itself—of course wouldn’t have surprised Wojnarowicz, whose work is directly concerned with the death march of global capitalism. In his writing, he frequently invokes the government-upheld illusion of a “onetribe nation,” which attempts to stamp out difference and corral us deeper into what the artist called “the pre-invented world.”2 For Wojnarowicz, the power of the imagination and speaking private truths publicly both provided key antidotes.

Andreas Sterzing, Gagging Cow Mural by David Wojnarowicz at Pier 34, New York, 1983. © Andreas Sterzing. Courtesy of the artist.

If these themes remained more or less consistent throughout the short span of the artist’s career, his process of conveying them grew increasingly nuanced. A former teenage hustler, he was essentially self-taught, apart from a brief time in high school art class. In the overwhelming number of paintings, prints, photographs, films, sculptures, and collages presented in the Whitney show, we see Wojnarowicz rapidly develop as an artist. His trajectory and output are staggering, especially given the length of his production: just over a decade. Following his Rimbaud photographs, he began making crude stencils developed for posters and promotion for his no-wave band 3 Teens Kill 4. They feature a house on fire, a falling man, a bull’s-eye, and soldiers in combat: in total, a scene of urban warfare. Other staples from Wojnarowicz’s visual vocabulary include maps, globes, and money. Initially, he spray-painted this imagery unadorned, like pictographs, on paper and board. In the exhibition’s most atmospheric room, where 3 Teens Kill 4’s version of “Tell Me Something Good” played in the background, examples hung salon style on a black wall alongside similar images screen-printed, painted, and collaged on supermarket posters. A particularly pointed example, Sirloin Steaks (1983), juxtaposes the discount meat on offer with an outline of a choking cow above a bullet striking a soldier’s bare white chest.

David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night, installation view, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, July 13–September 30, 2018. Photo: Ron Amstutz.

Rarely subtle and never coy, the work’s power seems to come not only from an urgent rage at the status quo, but also from Wojnarowicz’s attraction to language and his acute desire to comment meaningfully on the state of the world. Many of his paintings and, later, photographs are broken up into grids of images that build sequentially. His painting The Death of American Spirituality (1987), for instance, is divided into four square panels, each connected by a twisting, blood-engorged artery. The depiction of a Native Kachina doll in the first panel gives way to a plugged-in industrial monster in the second, followed by a cowboy and, finally, the disembodied head of Christ. A number of other paintings appear as fever visions or dreams, where violent actions unfold above the body of a sleeping man, as in the densely layered History Keeps Me Awake at Night (For Rilo Chmielorz) (1986). Still others are based on Wojnarowicz’s own dreams (which he meticulously recorded), such as the atypically serene Something from Sleep III (For Tom Rauffenbart) (1989). The vision of this ethereal image of a male outline suffused with planets, stars, and galaxies came to Wojnarowicz as something of a reckoning with his own mortality after he was diagnosed with AIDS in 1988.3

David Wojnarowicz, Something from Sleep III (For Tom Rauffenbart), 1989. Acrylic and spray paint on canvas, 48 1/2 × 39 × 1 5/8 in. Collection of Tom Rauffenbart. Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York.

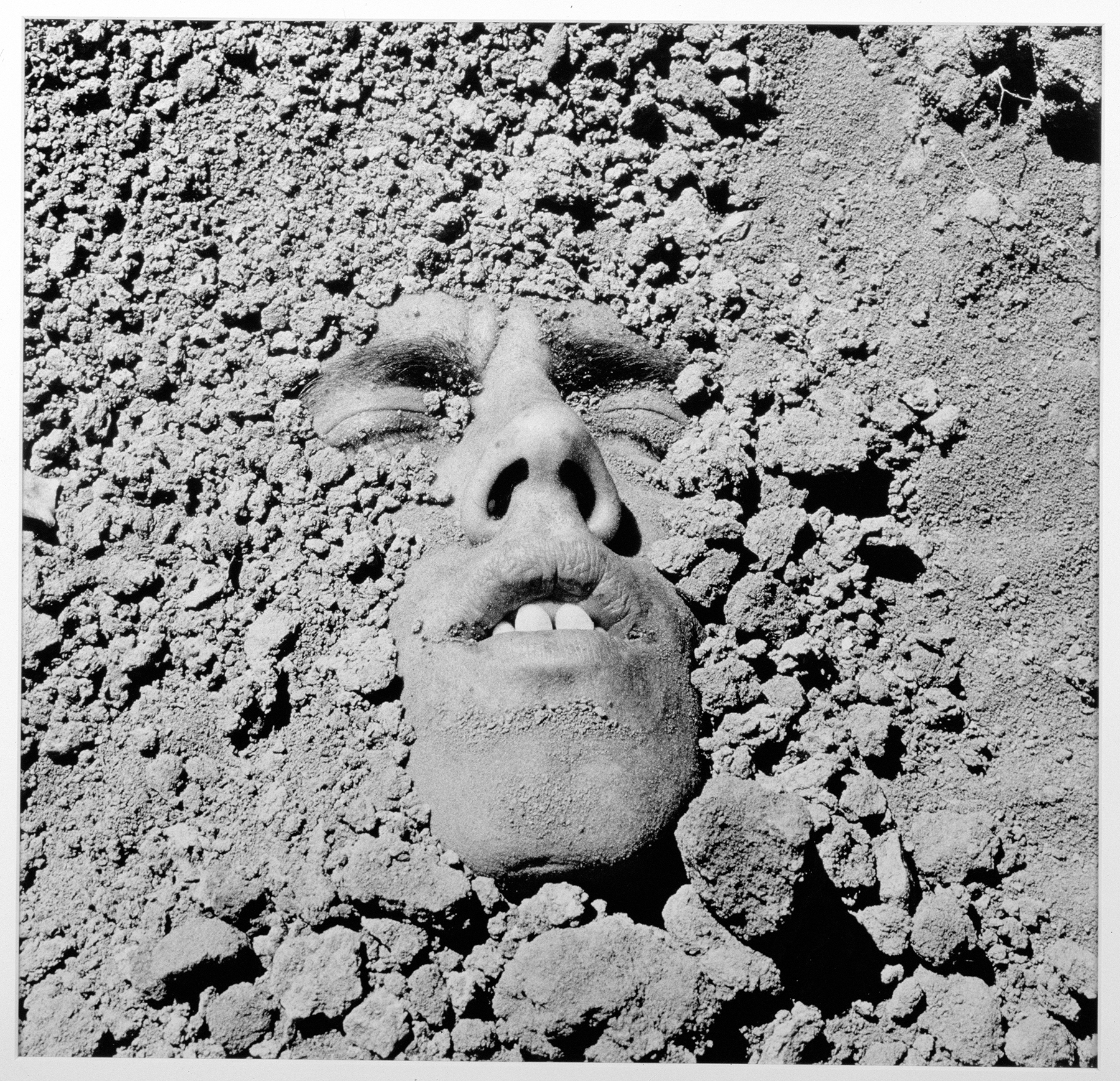

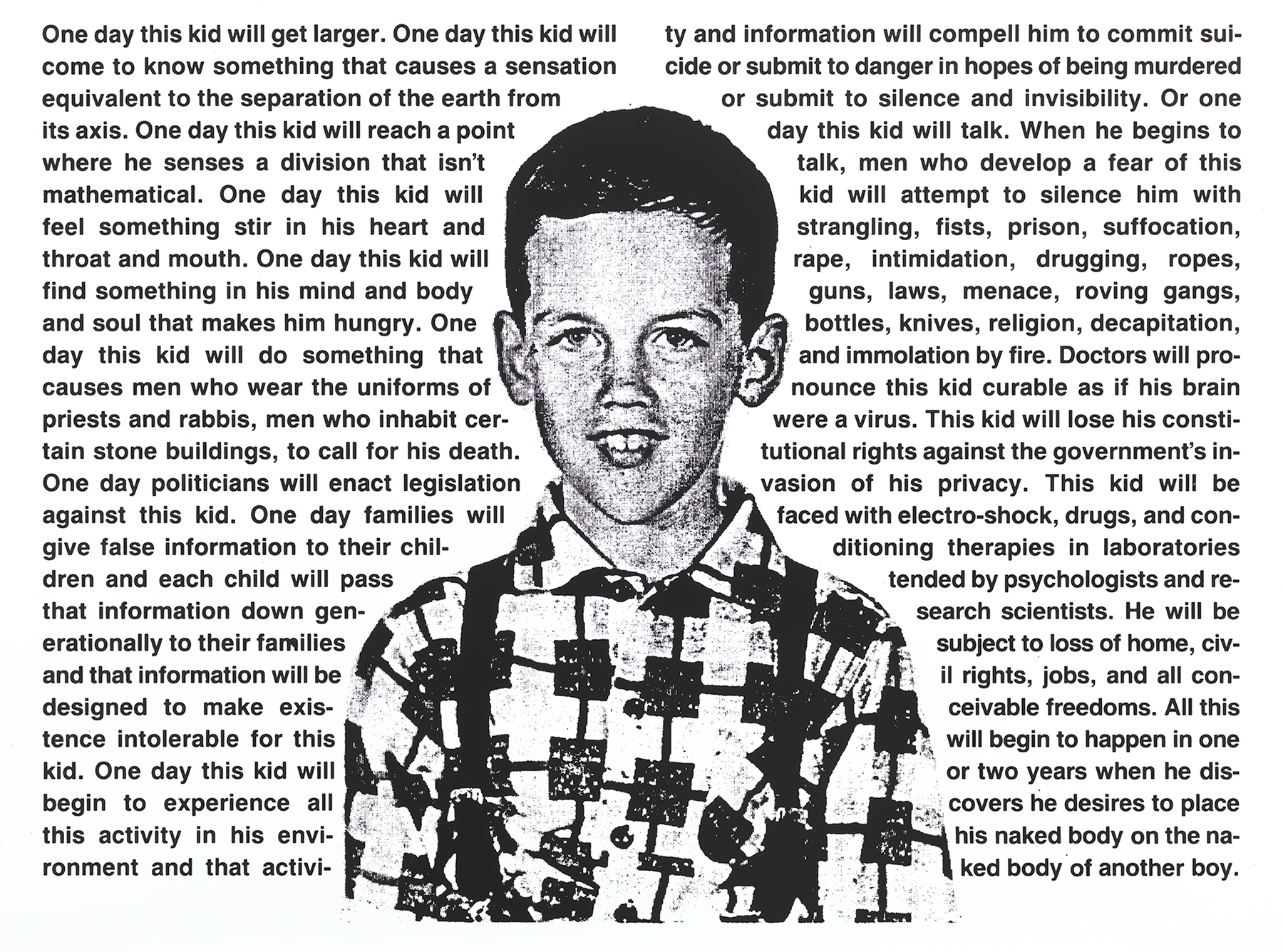

Wojnarowicz’s paintings exhibit both rawness and intricacy, but their sheer size and number threatened to overtake the other works in the show, particularly the smaller photographs and photo/text pieces, which are equally powerful, if not more so. Here Wojnarowicz concentrated his imagery, stripping down his approach and sacrificing some the visual polyphony of his painting. The photograph Untitled (Face in the Dirt) (1991) is an enigmatic single image. Intended as Wojnarowicz’s final work, it shows him buried up to his eyes, as if in an early grave. It could also be read as an emergence myth, as Lucy Lippard has suggested: a picture of the artist giving birth to himself from prima materia.4 Created with a Photostat machine, Untitled (One Day This Kid) (1990–91) is perhaps Wojnarowicz’s most reproduced work. Its bold black-and-white design resembles something from mass media, while the list of abuses that await the young, unassuming, queer Wojnarowicz pictured in the piece’s center are less assimilable. The deeply sincere and moving What is this Little Guy’s Job in the World (1990) also depicts a vulnerable creature: a small block of text questions the meaning of the mortality of a tiny frog shown climbing on a person’s hand.

Since much of this work was made at the end of Wojnarowicz’s life, it was jammed into the final few galleries of an exhibition that, overall, would have benefitted from a riskier organizing principle than chronology or medium. Arranged as it was, the show didn’t elucidate the compound breadth of Wojnarowicz, a cathartic artist whose most potent material was his vulnerability and emotion. A greater emphasis, therefore, should have been placed on ephemera, such as writing and performance—modes of address that more readily convey the artist’s presence. Though one gallery was given over to a reading Wojnarowicz held at the Drawing Center, in New York, and a few of his journals were on display, these inclusions felt paltry. The exhibition also seemed to flatten a history relevant to the artist, who often worked collaboratively and was grouped in with the East Village scene of the early 1980s (though Lippard has argued that Wojnarowicz should be considered among the ranks of a previous generation, such as Dan Graham and Robert Smithson, with whom he shared an affinity for post-industrial landscapes and geological time, among other themes).5 Apart from the images in Sterzing’s slideshow, which illustrate a range of approaches to subject matter similar to Wojnarowicz’s and a collective joy at the transgression of putting images directly on the wall, there were few examples of contemporaneous artwork and not more than a passing reference to the alternative galleries and spaces, such as Civilian Warfare, Gracie Mansion, and P•P•O•W, that supported Wojnarowicz’s rise to notoriety. This period has surely been covered elsewhere, but the lack of additional scholarship or context gave the exhibition a generic, unmoored feeling. It wasn’t clear what was at stake for the curators, David Breslin and David Kiehl, apart from Wojnarowicz’s biography and his outsider singularity. Julie Ault, in her catalog essay, “Notes Toward a Frame of Reference,” redresses some of these absent, wider concerns by collecting the voices of many of Wojnarowicz’s peers. Their quotations reckon with the effects of surviving a continuing AIDS epidemic, the chimerical freedoms of a pre-gentrified New York, and the complicity of relaxing into economic stability amidst the continuing inequities of today. “Am I one of the zombies,” one asks, “plugging along in the preinvented world that [Wojnarowicz] railed against?” 6

David Wojnarowicz, Untitled (Face in Dirt), 1992–93. Gelatin silver print, 28 1/2 x 28 1/2 in. Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York.

While ever ambivalent about his own commercial successes, such as his inclusion in the 1985 Whitney Biennial and sold-out painting shows, Wojnarowicz was deprived of some of these other quandaries, having died before midlife set in. But within his lifetime, AIDS demanded that he face and work through loss again and again. The untitled photographs displayed here of his mentor and closest friend, the photographer Peter Hujar, record this confrontation. One artist who couldn’t escape mention in the exhibition, Hujar met Wojnarowicz in 1981. Six years later, Wojnarowicz photographed him on his hospital bed moments after he passed away. The images of Hujar’s thin face and mouth ajar, his feet and hand peeking out from the bedsheet, are tender, but also brutally bare, a testament to Hujar’s humanity and the gravity of his loss to the world. After Hujar’s death, Wojnarowicz moved into his apartment, where he endured incessant, bitter negotiations with the landlord over the lease. (Eventually he settled out of court, promising to move out within 30 days if a cure for AIDS was found and not to pass the apartment on to anyone else with AIDS before he died.7) He began to use Hujar’s darkroom, and the flurry of photographs that came toward the end of his life are the result. Wojnarowicz also recycled Hujar’s porn collection for the works of photomontage in his Sex Series (1989). These reclamations were possibly as much a matter of access and tribute as they were a way to metabolize the injury of Hujar’s death and to critique its odious circumstances.

David Wojnarowicz, Untitled (One day this kid . . .), 1990–91. Photostat mounted on board, sheet: 29 13/16 × 40 1/8 × 3/16 in., image: 28 1/8 × 37 ½ in. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from the Print Committee 2002.183. Image © Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

The massive malfeasance and prejudice that fueled the AIDS crisis and became the center of so much of Wojnarowicz’s late work, as well as his activism with ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), aren’t hard to imagine today. Indeed, if some aspects of the time Wojnarowicz inhabited now seem as lost to the past as the piers, the political tenor of his era does not. The curators note that the timeliness of the show was not intentional—it had been in the works for almost a decade. Yet there is a depressing, eerie overlap between the “compassionate conservatism” and the culture wars of the 1980s, which targeted Wojnarowicz, and the Trumpist imbroglio of late. The present political darkness gives Wojnarowicz’s output a renewed immediacy that made the tameness of this exhibition that much more disappointing. Instead of going toward the palpable ferocity of Wojnarowicz’s work, the installation seemed to try counterbalance or “domesticate” it, as the Whitney’s director, Adam Weinberg writes in his foreword to the catalog.8 The decision to display a series of 23 plaster and collaged “mutant” heads, entitled Metamorphosis (1984), as aesthetic specimens under individual glass boxes, is perhaps the most blatant example. When originally installed by the artist at Gracie Mansion, the heads were lined up on a single shelf behind a painting of a target, in reference to a firing squad. Even the few unfinished Super 8 films projected in a gallery were all silent and more subdued than the grotesque gore fest of Where Evil Dwells (1985). The film, which the artist made with Tommy Turner, was based on the true story of a Long Island teenage murderer and Satan worshiper. ITSOFOMO (In the Shadow of Forward Motion) (1989), a gut-socking multimedia performance about the violent motivity of the AIDS crisis, which Wojnarowicz made with the musician Ben Neill, played in a separate theater at the museum for only a few nights. These curatorial minimizations and omissions present Wojnarowicz as a more pristine artist than he was. This is not to say that his work wasn’t beautiful or thoughtful or at times meditative. But most importantly, it was furious and intentionally abrasive to encounter. “Sometimes I wish I could blow myself up,” the artist once wrote:

Wrap a belt of dynamite around my fucking waist and walk into a cathedral or the Oval Office or the home of my mother and father. I’m in the last row of the bus, the seven other passengers are clustered like flies around the driver in the front. …I lean back and tilt my head so all I see are clouds in the sky. I’m looking back inside my head with my eyes wide open. I decide I’m not crazy or alien. It’s just that I’m more like one of those kids they find in remote jungles or forests of India. A wolf child. And they’ve dragged me into this fucking schizo-culture, snarling and spitting and walking around on curled knuckles.9

Perhaps there isn’t an apolitical or objective way to successfully institutionalize someone who saw himself so starkly in opposition to institutions and whose righteous indignation at the hypocrisies of morality, American style, feel like an infallible form of blood lust. Wojnarowicz had a knack for stepping outside the present and portraying a capacious version of history where disparate events were compressed together. Part of the resonance of his work is his long view, the deep and cosmic sense of time he affected. Like Walt Whitman, he wrote of and visualized himself as containing multitudes, and within a limited frame, his grasp of existence went as far forward as it did back. “I think history is a totally false subject,” he said into a tape recorder for a series of audio journals he kept, which were recently published by Semiotext(e). “I cut right through time, the same way I cut through borders when I rip up a map.” 10 Somewhere on this continuum, Wojnarowicz’s work seems to urge a starker grappling with the present than the one the Whitney exhibition provided. What kind of treachery has brought us here, it asks, and what type of picturesque ruins await?

Kate Wolf is a writer and editor in Los Angeles.