Particularly in relation to African American historical images, we need to find ways of incorporating them into social and political memory, instead of using [them] as a substitute which encourages the atrophy of such memory.

–Angela Y. Davis, Afro Images: Politics, Fashion, and Nostalgia

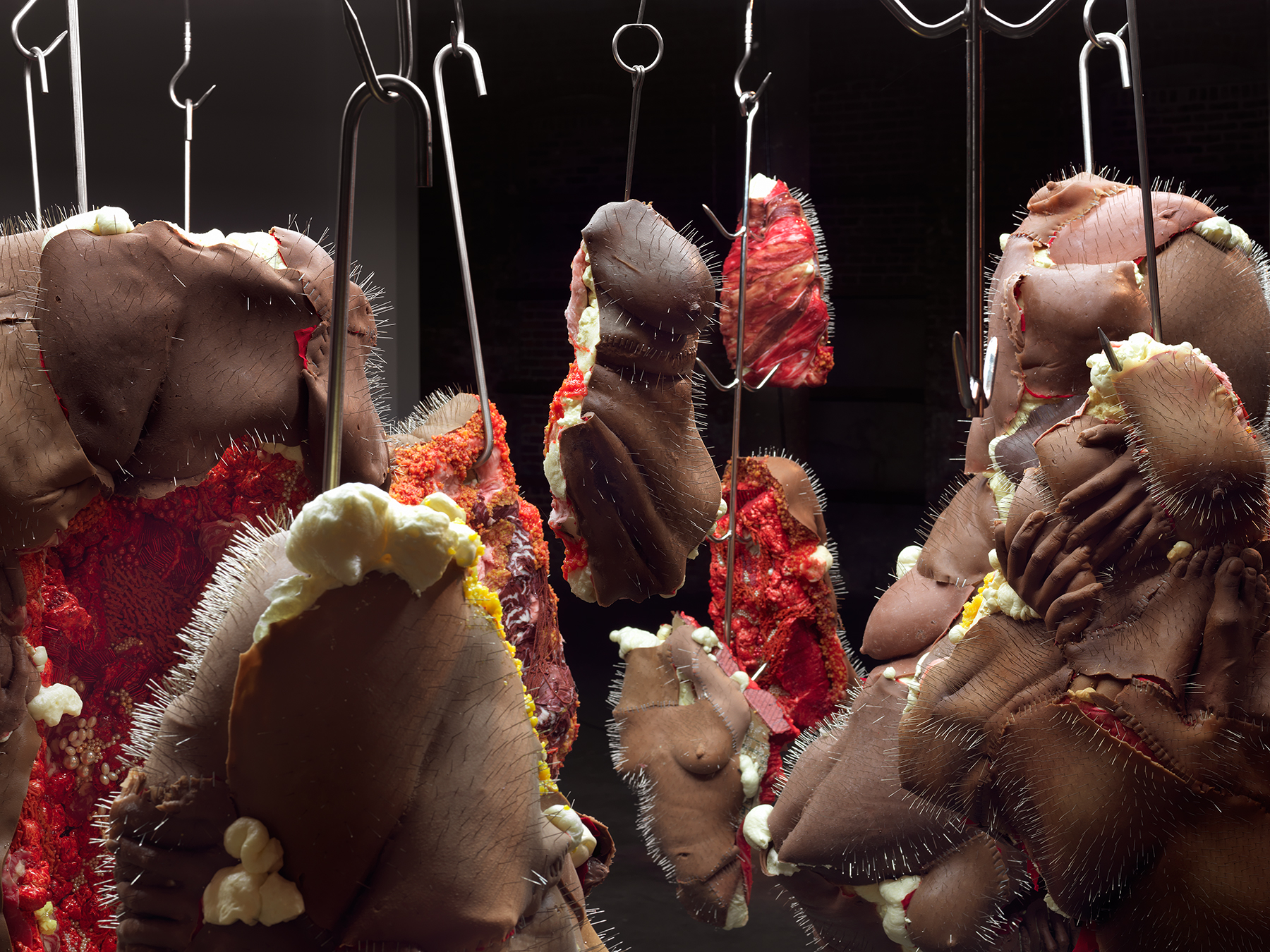

Doreen Garner, Rack of Those Ravaged and Unconsenting, 2017. Silicone, insulation foam, glass beads, fiberglass insulation, steel meat hooks, steel pins, pearls, 96 × 96 × 96 in. Courtesy of the artist and Pioneer Works, New York. Photo: Dan Bradica.

Visual and tattoo artist Doreen Garner’s interdisciplinary sculpture and performance practice considers the normalization and suppression of violent racist histories directed at the Black female body. Many of her works expose the brutality of Dr. J. Marion Sims, known as the “father of modern gynecology,” who has been canonized for his contributions to medicine despite the fact that his legacy was built on Black women’s degradation and suffering. In works such as PONEROS (2017) and Purge (2017), Garner literally knocks Sims off his pedestal and tears down the myth of heroism that surrounds his image. Her works educate viewers about suppressed racist medical histories embedded within the foundation of a nation built on slavery. Her exploration underlines slavery’s inhuman conditions, the pain Black women have endured, and the ways in which racism and sexism persist today. Garner’s works also examine the concept of White Monumentality, in which public statues uphold white supremacy.

Garner has extensively researched Sims’s legacy of inflicting abuse on Black female bodies to advance his medical career. Her scholarship informs many works, including Rack of Those Ravaged and Unconsenting (2017); A Fifteen Year Old Girl Who Would Never Dance Again: A White Man In Pursuit of the Pedestal (2017); Vesico Vaginal Fistula (2016) and “Not only had Sims to close the natural openings in the ravaged vaginal tissues; he had to make the edges of these openings knit together. He opted to abrade or scarify the edges of the vaginal tears every time he attempted to repair an opening. He then closed them with sutures and saw them become infected and reopen, painfully, every time” (2016). In deconstructing the image of Sims across several bodies of work, Garner highlights the urgent need to examine racism not only in one’s head but also in the world to show its structures in the everyday, including the dangers of passivity toward seemingly harmless and celebrated monuments that are commonplace in the public realm.

Garner’s recent works center on the fields of medicine and science, which are rife with violence directed at Black bodies and which contribute to the fetishization and sexualization of such bodies by wider society. Rather than resurrect Sims, this new body of work turns our attention to his victims and more contemporary examples of Black women who have been subjected to medical spectacle and racialized violence. For her most recent solo exhibition, She Is Risen, at JTT gallery, New York, in 2019, Garner invokes the ghosts of three of Sims’s victims—Anarcha Westcott, Betsey Harris, and Lucy Zimmerman—alongside Henrietta Lacks, whose cells were cultured in the 1950s without her knowledge or consent.1 Betsey’s Flag (2019) reimagines the American flag as a hanging sculpture of viscera. Pieces of brown silicone skin emulating various parts of the body are stapled together; on one side, incisions cut in the shape of stars reveal striations of fat and flesh. The reverse shows the layers beneath, made from Garner’s signature materials—silicone, glass beads, staples, plexiglass, steel pins, and urethane foam shaped to resemble human organs. In the exhibition, Garner makes the small leap from these four women, whose bodies were used for others’ gain without their consent, to Sandra Bland, who died under suspicious circumstances while in police custody in 2015.2 In Heard From Her Larynx: Sandra (2019), a gramophone, made of pink flesh covered in body hair and symbolizing a larynx, plays an audio recording of Bland’s arrest. The sculpture speaks to the persistent threat of racist police violence to Black women (and all Black lives). Together, these works address many ways institutions have failed Black women.

Doreen Garner, Betsey’s Flag, 2019. Silicone, glass beads, staples, plexiglass, steel pins, urethane foam, 60 × 43 × 5 in. Courtesy of the artist and JTT, New York. Photo: Charles Benton.

In Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America, Saidiya Hartman speaks of the urgency to remedy this pervasive threat against Black bodies:

Redressing the pained body encompasses operating in and against the demands of the system, negotiating the disciplinary harnessing of the body and counterinvesting in the body as a site of possibility. In this instance, pain must be recognized in its historicity and as the articulation of a social condition of brutal constraint, extreme need, and constant violence; in other words, it is the perpetual condition of ravishment. Pain is a normative condition that encompasses the legal subjectivity of the enslaved that is constructed along the lines of injury and punishment, the violation and suffering inextricably enmeshed with the pleasures of minstrelsy and melodrama, the operation of power on Black bodies, and the life of the property in which the full enjoyment of the slave as thing supersedes the admittedly tentative recognition of slave humanity and permits the intemperate uses of chattel.3

Garner takes up Hartman’s call, actively liberating the pained bodies of Black women by addressing trauma that has been overlooked. The violence Garner probes often has been justified historically in the name of medical contributions, which were seen to outweigh the moral and ethical rights of the Black women whose bodies were experimented on. She adopts an artist-as-surgeon role to counter the medical gaze, which Michel Foucault describes thus: “By reciprocity, the clinician’s gaze becomes the functional equivalent of fire in chemical combustion; it is through it that the essential purity of phenomena can emerge: it is the separating agent of truths.”4 Examples of this medical gaze include doctors modifying patients’ stories to fit into recognized biomedical paradigms and selecting data that serves their purposes while ignoring other details. Garner’s visceral works turn the body, rendered in silicone and other materials, inside out; her fragmented replica organs serve as fleshy recollections of traumatic histories that she—as the artist-surgeon—excises.

Doreen Garner, Heard From Her Larynx: Sandra, 2019. Silicone, synthetic hair, electronics, wood, brass, 60 × 14 × 14 in. Courtesy of the artist and JTT, New York. Photo: Charles Benton.

Garner specifically contests the medical practice of Sims, who performed his experimental operations on enslaved Black women without consent or anesthetics in order to perfect his procedures to correct vesicovaginal fistulas, “abnormal openings between the bladder and the vagina that result in continuous and unremitting urinary incontinence.”5 Many of his “patients” were women he purchased and kept. Anarcha Westcott endured Sims’s invasive procedure over thirty times before he finally closed her fistula. During his public procedures, Sims exhibited dangerous and disturbing scientific racism, purporting Black people had “thicker” skin and did not feel pain, a belief that he used to justify not giving his victims anesthesia. Sims is still lauded for this work by the current medical establishment, which resists reevaluating a nineteenth-century physician by today’s ethical and moral standards.6

In the joint exhibition White Man On A Pedestal (WMOAP), which took place at Pioneer Works, in Brooklyn, in 2017, Garner and artist Kenya (Robinson) addressed their experiences as Black women working within systems of white supremacy, white monumentality, and historical erasures. Garner’s contributions included a series of sculptures: PONEROS, The Skin of Poneros (2017), the aforementioned Rack of Those Ravaged and Unconsenting, and a collaborative performance titled Purge.

PONEROS is a fifteen-foot-tall, 3D-printed foam copy of the bronze statue of Sims that stood in Central Park at the time of Garner’s exhibition. The removal of Sims’s statue, on April 17, 2018, brought Garner’s work into dialogue with ongoing calls for the removal of contested statues in the United States and around the globe, a movement that signals that, although society is evolving, structural racism remains intact.7 PONEROS translates from the Ancient Greek as “Evil One,” and the artist painted her version in blood-red polyurethane. The Skin of Poneros comprises a silicon form peeled from her sculpture of Sims and set in a coffin illuminated by red light. The sculptural installation Rack of Those Ravaged and Unconsenting consists of lifelike assemblages of body parts made from silicone, expanded foam, and meticulously placed pearls, Swarovski crystals, and glass beads. The fleshy chunks dangle on hooks from a rack, similar to those found in abattoirs, suspended from the gallery ceiling. As is common in a number of Garner’s works, the viewer’s attention is drawn to the sutured skin and layers of flesh and fat hidden beneath the epidermis. A red-lined vitrine displayed surgical instruments, on loan from the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia, similar to the kinds of tools Sims used for his operations.

Doreen Garner, PONEROS, 2017. Foam, blood-tinted polyurethane, 216 1/2 × 48 × 48 in. Courtesy of the artist and Pioneer Works, New York. Photo: Dan Bradica.

The exhibition closed with an hour-long performance of Purge, an interplay between the politics of pain and the abuse of power. Garner and her collaborators executed a vesicovaginal fistula operation on the silicone skincast of her Sims sculpture in front of a seated audience.8 This public setting was comparable to the way Sims demonstrated his procedure on Anarcha Westcott, who was subjected to thirty surgeries, in an operating theater. Garner’s performance offers abjection as an aesthetic and critical strategy for understanding the intergenerational trauma that is the legacy of slavery. Racialized science and biological fallacies justified slavery, and these ideologies still contribute to perpetuating stereotypes and stigma around Black women and deny Black people the right to feel pain. Contemporary understandings of Black pain bear the weight of these fraught communal failures, as one can observe in cases of police brutality, lack of access to affordable healthcare, the penal system, and all of the institutions that continue to fail Black people and subject them to violence. By literally and physically using performative action to dismantle the image of Sims, Garner’s works serve as both protest and corrective.

Doreen Garner, Purge, 2017. Live performance during White Man On A Pedestal: Doreen Garner and Kenya (Robinson), Pioneer Works, Brooklyn, NY, November 30, 2017. Courtesy of the artist and Pioneer Works, New York. Photo: Lexie Moreland.

The artist and her collaborators do not seek transgression for transgression’s sake but rather to confront the authority of white monumentality. In Garner’s words, “Purge is not about creating gruesome work, it is about creating a work that has subtle nuances where you don’t know completely how to feel, and maybe that’s what stays with you.”9 As feminist Betita Martínez reminds us, white supremacy “is an historically based, institutionally perpetuated system of exploitation and oppression of continents, nations, and peoples of color by white people and nations of the European continent, for the purpose of maintaining and defending a system of wealth, power, and privilege.”10 Garner’s performance of Purge rips apart the dominant white male narrative.

In addition to revealing ongoing abuse against Black women’s bodies, Garner seeks to subvert the (male) medical gaze and offer Black women openings for pleasure in experiencing her works. Jared Richardson notes that an earlier performance work, The Observatory (2014), “evokes a metaphorical nexus between body, flesh, organs, and land—a move that integrates archaeological and clinical gazes into a black female optic of pleasure wherein an oppositional gaze disidentifies the theatrical and scopophilic framing of black women’s bodies.”11 The Observatory saw Garner offer up her body sacrificially to the viewer in an hour-long performance exploring the links between the medical gaze, disgust, and sensual and sexual fascinations. The artist contorted her body to fit into a transparent vitrine that was filled with stuffed condoms that had the appearance of organs, synthetic hair, and slatherings of petroleum jelly and glitter. The documentation of this work on Garner’s website shows the artist’s gaze fixed on the camera—unflinching and confrontational.12 In the live performance, Garner selected audience members and fixed her gaze on them for a period of time as they walked around the vitrine, while she lay and adjusted her body in what was clearly an uncomfortable space. She displayed her body as if dissected, put on public display and surrounded by viscera, in a direct reference to the nineteenth- and twentieth-century public exhibitions of Black and Indigenous peoples’ bodies in “human zoos,” where they were caged in “natural” habitats.

Doreen Garner, The Observatory, 2014. Video still. Video, 60 min. Courtesy of the artist and JTT, New York.

By putting herself into this observational frame as a form of performative self-sacrifice, Garner complicates the dynamics of bearing witness to her work and actively destabilizes the power and politics of viewing the Black female body for her audience. Garner explores pain’s potential as a tool for engaging in the critical labor of redress, pointing to pain’s relationship to Black bodies as part of both a difficult past and the narrative of an ever-unfolding present. Enslavement has left an intergenerational legacy of trauma that is too often underrecognized or erased. Garner’s work considers the impact of past injuries on the current state of Black lives, which are still the targets of injustices that undermine a collective sense of group identity, values, meaning, and purpose.

X—

Jareh Das is a Lagos- and London-based curator, writer, and researcher. She holds a PhD in Curating Art and Science from Royal Holloway, University of London, for her thesis Bearing Witness: On Pain in Performance (2018).