An appreciation for artist and writer Margi Scharff (1955-2007)1

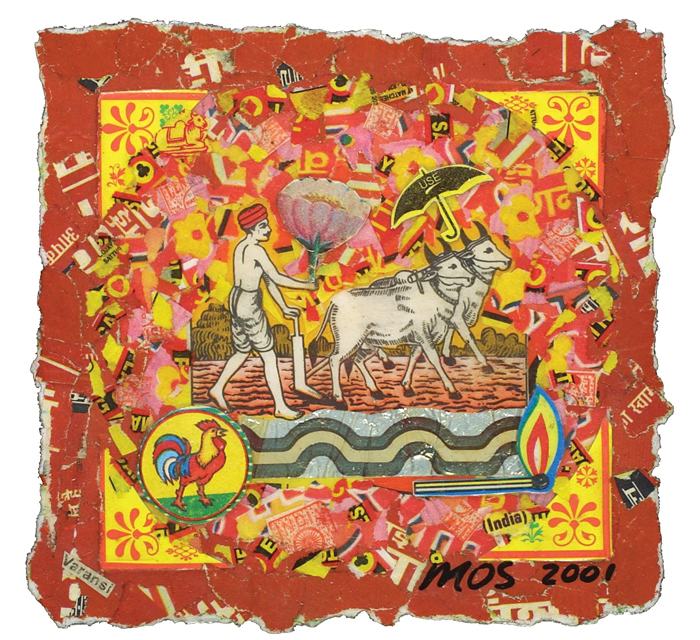

Margi was barely five feet tall and under one hundred pounds, even before she became ill. Nevertheless, she was a passionate force to be reckoned with. She spent the last eight years of her life traveling—alone—throughout Southeast Asia. She exuded warmth that drew people to her wherever she went. She was open and trusting while at the same time possessed the street smarts of a seasoned world traveler. If she found a clean, cheap room with a table at which she could work, she would make it her home for a while, settling down to assemble delicate collages from tiny fragments of detritus, such as candy wrappers and matchboxes, picked up along the road wherever she found herself.

Once her journey began, Margi gave up her tiny shack perched on a cliff above the Pacific Ocean outside of Tijuana. She would return to her base in Los Angeles long enough to raise sufficient funds to get back on the road. She appeared to have no care for possessions beyond the minimal amount needed to sustain travel and artwork. Whenever she came to town, her many friends would rally around, offering up assistance of all kinds—a place to stay, introductions, opportunities to show and sell her work, help with writing grants, whatever else was needed. Margi’s support system was extensive, even before her illness. It seemed as if her ardent convictions about her artwork and the way she lived her life compelled her many supporters to help her. I suspect that I wasn’t the only one who, lacking the gumption to take off like a vagabond on my own, treasured the vicarious pleasure of her vivid and humorous stories. Like her collages, Margi’s stories were dense, vibrant and keenly observed.

When Margi recovered from ovarian cancer in India in 2006 despite a grave prognosis, I was relieved but not entirely surprised, given her ferocity of will. At her opening at Overtones in Los Angeles in May of 2007, I was shocked to see how fast a second bout of cancer was overtaking her by-then fragile body. Margi died in Tiburon, California, on July 2, 2007, surrounded by close friends and family. I’m told that, although she was weak and stoned by the copious drugs she’d ingested, she was characteristically ebullient. “She jumped up to stand on the porch that overlooked the entire San Francisco Bay. It was an exquisite summer afternoon; the sun sparkled off the water and she called me over to admire its beauty. She said goodbye to everything of this world, took my hand and led me back inside.”2 When she died later that night, Margi left us with the considerable challenge of honoring her intrepid spirit.

Elizabeth Pulsinelli

The Art of Laundry (Varanasi, 2001)

Margi Scharff

…Thwuuwaaappp!Thwuuwaaappappph!!!Thwuapp!! This was the early-morning sound of laundry being washed on the shores of the ancient and holy River ganges. The laundry sounds begin just before dawn as a single slap of wet fabric is slung down hard on one of the stone washing slabs that dot the river’s edge. Then, as more washers join in, the slapping sounds build and blend in syncopated rhythms. After washing, the laundry is dried by laying out each piece flat on the steps of the ghats, allowing the sun-warmed stone to do the work. Solar energy at its best. No dryer. No ironing. By 11 a.m. the wind kicks up and laundry time is over for the day.

My balcony at vishnu Resthouse was situated just above one of these laundry spots so that I could see the whole operation from a bird’s-eye view. After watching a woman laying out a row of colorful saris edge to edge, I felt compelled to go down and tell her how beautiful the patterns and colors looked from above. It was a real show—fabulous as a giant painting. The woman’s name was Reka and I could see in her eyes and in the way she tilted her head to the side as she listened that she was imagining what I had seen. As it happens, my own family is in the laundry business, and so for a short while we talked and laughed about laundry. when I returned to my balcony I looked down again, knowing Reka would be looking for me, and we both waved.

The next morning when I looked down to the ghats to watch the laundry show, Reka was already looking up. She signaled for me to come down, and then she led me to a slanted embankment where she had perfectly laid out 100 sheets, edge to edge in an enormous rectangle. The sheets were blue on the outside, fading to white in the center. It was stunning. Reka was silent for a moment while she watched me take it all in. Then she lifted her arm in a theatrical gesture, pointing at the layout of sheets. “This is my work today,” she announced with a smile.

Reprinted with permission from Margi Scharff: On India Time (Los Angeles: Overtones Gallery, 2008).