In today’s world, boundaries are fixed, and most significant facts have been generated. Gentlemen, the heroic frontier now lies in the ordering and deployments of those facts. Classification, organization, presentation. To put it another way, the pie has been made—the contest is now in the slicing. Gentlemen, you aspire to hold the knife.

–David Foster Wallace, The Pale King1

The astringent voice of the substitute teacher in Wallace’s novel conjures something paramount and potentially violent in contemporary artistic production. All of these procedures—classification, organization, and presentation—follow the logic of preservation. But what is possible when we set down the metaphorical knife and pick up the literal knife (or sledgehammer, screwdriver, excavator, etc.) and give in to destruction? Recent museum exhibitions have taken up destruction as production and the accompanying concerns of immateriality and existentialism. Destroy the Picture: Painting the Void, 1949–1962, at the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles, focused on postwar works aggressively undoing the two-dimensional picture plane. More contemporary and multi-dimensional, the Hammer Museum’s 2011 invitational, All of this and nothing, brought together recent works steeped in transformation, fragmentation, and the formless. Adopting varied approaches to production as destruction, three contemporary artists—Eduardo Abaroa, Cyprien Gaillard, and Henrik Olesen—proceed by navigating configurations of destroyer and destroyed.

Eduardo Abaroa, Total Destruction of the Anthropology Museum, 2012. Installation view at kurimanzutto. Courtesy of the artist and kurimanzutto.

The artists in Destroy the Picture are cast against the trauma of World War II, but the contemporary artworks discussed here cannot be viewed against such a determined backdrop. The economic collapse in 2008 instigated broad effects on all creative workers, leaving less funding, fewer jobs, and diminished prospects. However, prior to the fallout, the accelerating conditions of semiocapitalism (such as labor and leisure time becoming steadily indistinguishable) laid the ground for artists to become reinvested in interrogating the politics and ideologies that drive institutions and economies.2 The unrelenting pace of technology is partially to blame for the temporal fusion addressed by Abaroa, Gaillard, and Olesen. The ruin of 2008 occurred with the help of the digital movement of money and communication—immaterial in form but vastly powerful over a multitude of materials (houses most conspicuously) and bodies. The power of these digital currents is exacerbated by the precision of the digital copy/code that indefatigably replicates and spreads out in viral fashion. To undo these invisible congealed flows, they must be corporealized. These three male artists each carries with him a self-selected patriarch to act as an effigy for an ossified history in need of slicing.

The other form on the chopping block is the substitute. The works of Abaroa, Gaillard, and Olesen analyzed here often wrestle with the replica or the surrogate. These substitutes, inherently separate and in excess of what they stand in for, have agency in a negative economy and are able to play a trick that causes bifurcation and rupture in a contemporary fusion of chronology that points to a perpetual now.3

Razing the Museum

In July of 2012, I joined a group of students in the SOMA summer program for a tour of the Museo Nacional de Anthropología in Mexico City, led by the artist Eduardo Abaroa.4 The museum opened in 1964 during the long reign of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), and reflected and coincided with a vision of national identity promoted by the PRI. Architect Pedro Ramírez Vásquez’s modernist design was seen by many critics as ideologically synonymous with the political party that supported its creation, as well as their political corruption. Moving through the exhibition halls, Abaroa’s narrative expanded far beyond the scope of the wall didactics. He claimed allegiance with the critique of the museum in Octavio Paz’s poetic and scathing essay “Critique of the Pyramid” (1969).5 Without being overtly performative, the tour had a scripted quality, reminiscent of Andrea Fraser’s institutional critique from Welcome to the Wadsworth (1991). The complexity and dialogue generated through the outlying nodes of political, religious, and historical information Abaroa brought into the room undercut the petrified national identity presented in the vitrines and illustrations of the museum’s vast galleries. The “exaggerated” and “impoverished” representations were most egregious in the postcolonial stereotyping of the ethnographic halls on the second floor.6 In one exhibit, Abaroa pointed to a display representing a contemporary indigenous population known for their refusal to speak to outsiders and asked the tour group to consider the efficacy of that model as a form of resistance to exploitation.

Eduardo Abaroa, photograph of the guided tour, from the project Total Destruction of the Anthropology Museum, 2012. Courtesy of the artist and kurimanzutto.

We entered the Mexica-Aztec exhibition hall along a grand white marble walkway. Inside, we crowded around the massive statue of Coatlicue. This mythic Aztec mother earth deity conceived Huitzilopochtli, god of sun and war. His birth was the catalyst for a series of deaths. First Coatlicue is beheaded by her other children, and then they are in turn killed by the new son.7 Abaroa explained that this religious totem had been so potent that it was reburied after excavation by the Spaniards to prevent unwanted worship by the Aztecs. The crux of Paz’s critique, enacted here through our guide, reveals that the thread of domination originating with the Aztecs was replicated by the Spaniards and then by the presidents of Mexico, as each successive group gained control of the territory. The museum itself constructed under this corrosive scepter had no other potential than to similarly infect the represented histories of Mexico and Mesoamerica in its walls.8

Upon exiting the final exhibition hall, Abaroa showed a set of printed photographs from his recent exhibition at kurimanzutto gallery, which had closed before the tour. The first images from his project, Destrucción Total del Museo de Anthropología (The Total Destruction of the Anthropology Museum) (2012), were step-by-step plans, based on the expertise of a demolition civil engineer, to destroy the museum’s structure along with all its contents. The series of color-coded maps indicated various demolition techniques (recycling, expanding concrete, excavating, manual cutting). The images of the kurimanzutto gallery showed a pile of rubble in the middle of the floor with sculptural replicas of museum artifacts simulating their post-destruction state.9 Within the pile was a sculpture depicting a human skull in the center of the sun’s rays, symbolizing the dialectical relationship of life and death.10 It is a replica of the Disco de la Muerte (Disc of Death), originally an Aztec basalt piece. In the heap at kurimanzutto, Abaroa’s replica of Disco de la Muerte is just as damaged, which is to say, just as preserved, as it is in the museum. This substitute, a body double, hovering between destroyed and intact, brings questions of authenticity and originality of the copied artifact into relief. Overall, the exhibition expertly mimicked the museological format. On the wall, vinyl letters state, “El cuidado que se tuvo en la construcción de la obra le ha dado una seguridad absoluta en su permanencia en el tiempo….” This statement, by Pedro Ramírez Vásquez, translates from the Spanish as, “The meticulous care that we took in constructing this building has absolutely guaranteed its permanence in time…” Abaroa appropriates this statement and reorients it to his vision of destruction presented in the room.

Eduardo Abaroa, simulated debris from the project Total Destruction of the Anthropology Museum, 2012. Prehispanic sculpture replicas, museum guides and souvenirs, Mexican handcrafts, marble, volcanic rock, and concrete. Courtesy of the artist and kurimanzutto.

Abaroa’s project took Paz’s critique as a script, but it also referred to Ben Vautier’s Fluxus work Total Art Matchbox (1968).11 Like the recipient of a Vautier matchbox who could follow the instructions printed on the vessel, beginning with “USE THESE MATCHES TO DESTROY ALL ART…,”12 Abaroa followed the direction of Paz, and Abaroa’s audience similarly has the opportunity to consider his destructive fantasy. The tour had unmoored the authoritative voice of the museum and fractured the façade and the foundation in our minds. The intimacy in the reference to Vautier helps us make the imaginative leap to individually raze the museum in totality and make a split with its past.13 Abaroa’s tour was able to seamlessly fake authority amongst the numerous and simultaneous tours at the museum on any given day, but his replicas would be considered inadmissible inside the walls of the museum. Unlike souvenirs, which metonymically, and usually in miniature, reaffirm and authenticate the official narrative of the collection, Abaroa’s objects undermine the originals. He would be apprehended as a forger or thief for discrediting the collection, which bears a name given by the state. Rather than continuing the series of substitutes aligned with the lineage of dominance critiqued by Paz, Abaroa’s surrogates constitute a rupture, a complete recomposition, not just the inheritance of a blood line or a repeat performance with new players. Abaroa insists that to raze it all to the ground could be the best possible choice. Abaroa has no utopia or reformation to propose; instead, via negation, he asserts a temporary break in the flows of meaning forced upon this group of symbolic objects.

Demolish, Rebuild, Repeat

COATLICUE: You have no future.

CHRONOS: And you have no past.

COATLIQUE: That doesn’t leave us much of a present.

CHRONOS: Maybe we are doomed to being merely some “light-years” with missing tense.

COATLIQUE: Or two inefficient memories.

—Robert Smithson14

Tackling undoing another way, French artist Cyprien Gaillard appropriates destruction and employs its detritus as a readymade. In Gaillard’s exhibition this year at the Hammer Museum, architectural destruction was a common theme. In the center of the Hammer Projects gallery stood ten towering plinths topped with glass-encased industrial excavator parts. All named Untitled (Tooth) (2012), the entombed excavator bucket teeth were impotent, separated from the machines that once wielded them. Their pristine and phallic cases contrasted with the rust and wear that interrupted the warm yellow surface of the metal forms within. The vitrine tops were made of half-inch-thick glass and the off-white base structures looked like some type of impenetrable composite material; together they felt like a labyrinth of futuristic reliquaries.15 Each vitrine was placed under a brightly focused spotlight, which created a crisp curve on the floor below. This dramatic effect drew a direct comparison to the conventions of a natural history museum, but was almost garish, making each vitrine a stage, with the objects like cohorts about to begin a choreographed action in unison. In a natural history museum, these fragments would likely be placed in a single case, configured like bones to approximate the body they stood-in for. However, treated this way, the pieces spoke the language of serial art production.

Cyprien Gaillard, installation view at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, April 20–August 4, 2013. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer.

Although Gaillard found the excavator parts in a California desert junkyard, these ten artworks were shown first in Gaillard’s solo show, titled What It Does to Your City, at the Schinkel Pavillion in Berlin in 2012. That overarching title and the accompanying experimental performance were shed from the exhibit as presented at the Hammer. The Berlin performance, conducted in a lot visible from the Schinkel Pavillion, was a ballet choreographed for two excavators set to a live xylophone soundtrack. (I wonder if the robotic battles of Survival Research Laboratories made an early impression on the artist.) Gaillard’s work is well known for actively critiquing urban renewal projects all over the globe. However, in his Los Angeles exhibition, inertia dominated. Maybe the mythic blankness of the West was an apt setting for Gaillard to move into a new phase, affectively more passive, but as though transported to a distant future in which the materials on view have always already been buried, excavated, and formalized by preservative conventions. Here, without the reference of the performing excavators of the Schinkel exhibition, each tooth floated dislocated from its body into the slippery terrain of signification.

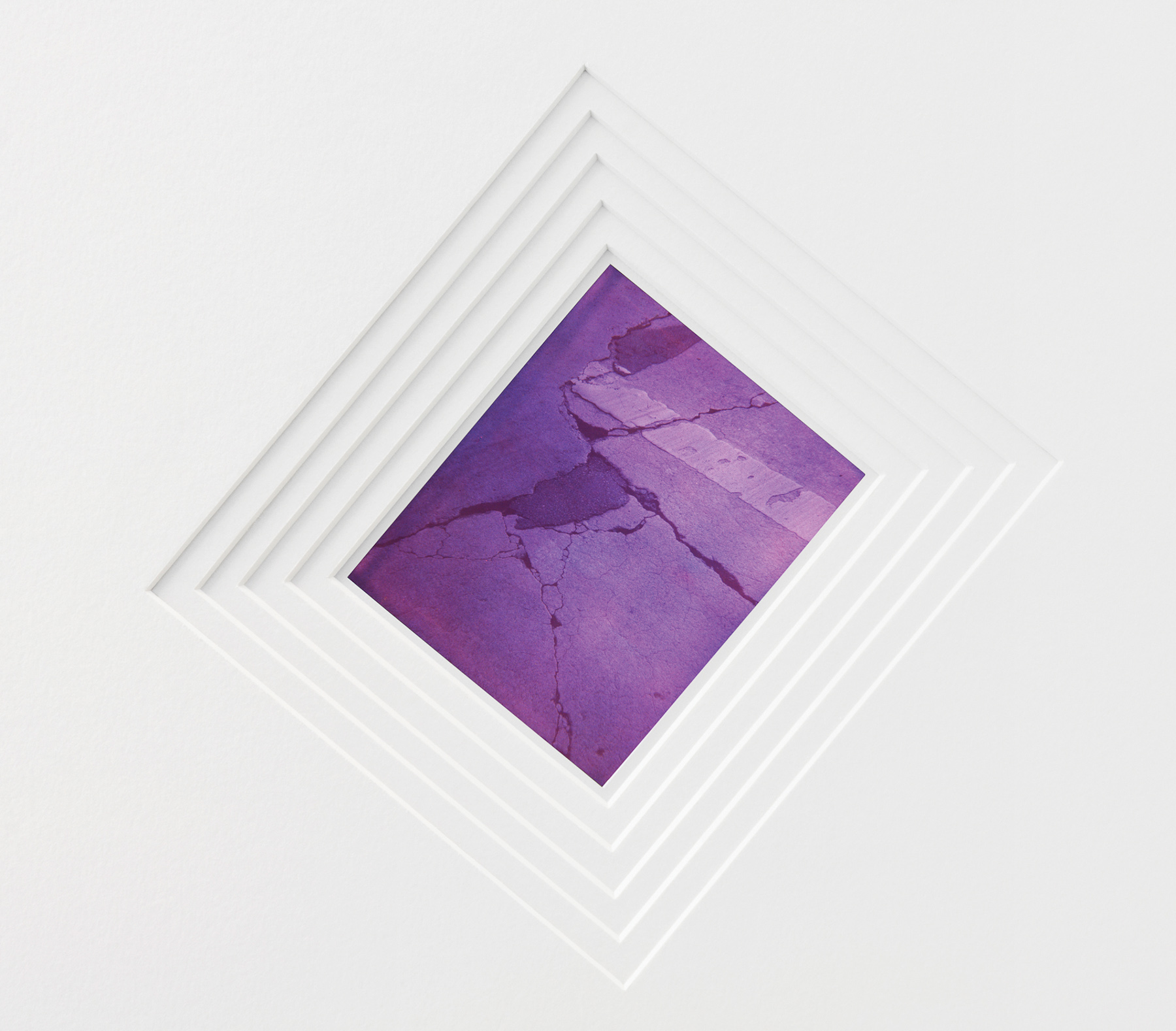

Gaillard subscribes to Robert Smithson’s entropic vision; his adoption of Smithson as a forefather is clear. Galliard’s group of twelve Polaroids, Westwood Cracks (Ice Age) (2012) were hung along two walls in the Hammer gallery. Each image showed a section of asphalt breaking apart, implicating pressures from above and below, indexically marking this icon of urban surfacing. The geologic time of the “ice age” can be linked to several of Smithson’s writings, but the Hammer’s literature tells us “…as soon as the photos came out of the camera, he [Gaillard] dipped them in the cooler so that the prints developed with intense purple and blue hues.” But those familiar with Polaroid film will note that these almost monochromatic hues indicate that the chemistry has turned; the goo that makes the instant image has expired. Each one in the series of Polaroids was sedimented beneath five layers of mat board and pitched at a 45-degree angle. The tiered layers of matting created the illusion of a ziggurat breaking apart from its center. The subtle shifts from conventional display (the angled images and oversized plinths) created a convincing displacement from present to future. One experienced time as vacillating: temporarily collapsed then distending in both directions. Smithson became another monument in the room. The works collected here practically illustrated Smithson’s essay “Entropy and the New Monuments” (1966), in which he described objects against the ages “involved in a systematic reduction of time down to fractions of seconds, rather than in representing the long spaces of centuries. Both past and future are placed into an objective present.”16 While it may not be accurate to describe Gaillard’s exhibition as an attempt to represent an “objective present,” future and past were co-present, almost like a top and a bottom, and we find ourselves in the middle like the crushed asphalt.

Cyprien Gaillard, Westwood Cracks (Ice Age) (detail), 2012. Twelve Polaroids with mats and aluminum and plexiglass frames; 40 1⁄8 × 28 3⁄8 × 1 5⁄8 inches framed. © Cyprien Gaillard. Courtesy Sprueth Magers Berlin London.

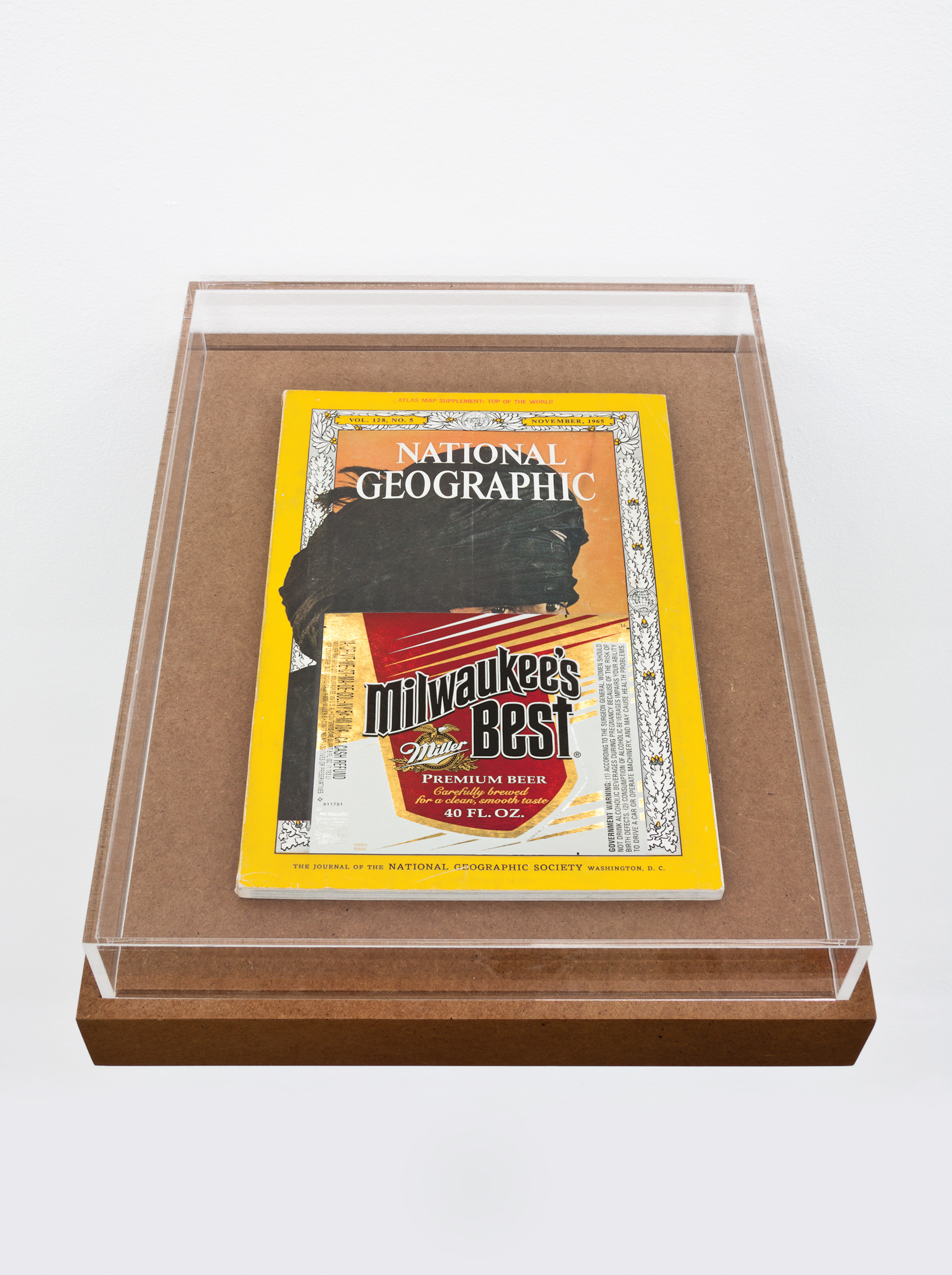

In Gaillard’s Untitled (National Geographic) (2012), another immaculate transparent case extended out directly from the wall and encapsulated an issue of National Geographic from November 1965, seemingly intact, with a Milwaukee’s Best beer label affixed onto the lower portion of the cover. The eyes of a male figure in a dark headdress are visible, but the label totally obscures the text listing the issue’s contents. If the label could slip free as easily as it must have from the cool condensation-covered bottle it came from, the first lines of text would say “St. Louis,” followed by the subheadings “New spirit soars in mid–America’s proud old city” and “Gateway to Western Expansion.”17 Gaillard has overwritten the text here, acting out a narrative of westward expansion by literally obscuring the history of St. Louis. This move reflects the globalization of beer and economic flows that lead us not only to the keg parties of students at nearby University of California, Los Angeles, but also onward to Mexico, if we consider the recent acquisition of Grupo Modelo by Anheuser-Busch InBev.18 But the fact that these connections are buried generates a relay of mediated experience. Seemingly antithetical to nostalgia, the problem here is the capacity of the image’s thin membrane to be just as opaque as it is transparent, which is true of all the materials Gaillard brought to the Hammer. Binding a map through tangential associations across numerous territories, Gaillard never goes deep. Instead of trying to progress or clarify, he is content to share his fragmentary, recombinatory objects to remind us that destructive work is constantly mirroring life’s activities, whether sanctioned, invasive, or entropic.

Cyprien Gaillard, Untitled (National Geographic), 2012. National Geographic magazine, beer label, showcase; 3 1⁄4 × 11 × 13 7⁄8 inches overall. © Cyprien Gaillard. Courtesy Sprueth Magers Berlin London.

Touch Screen

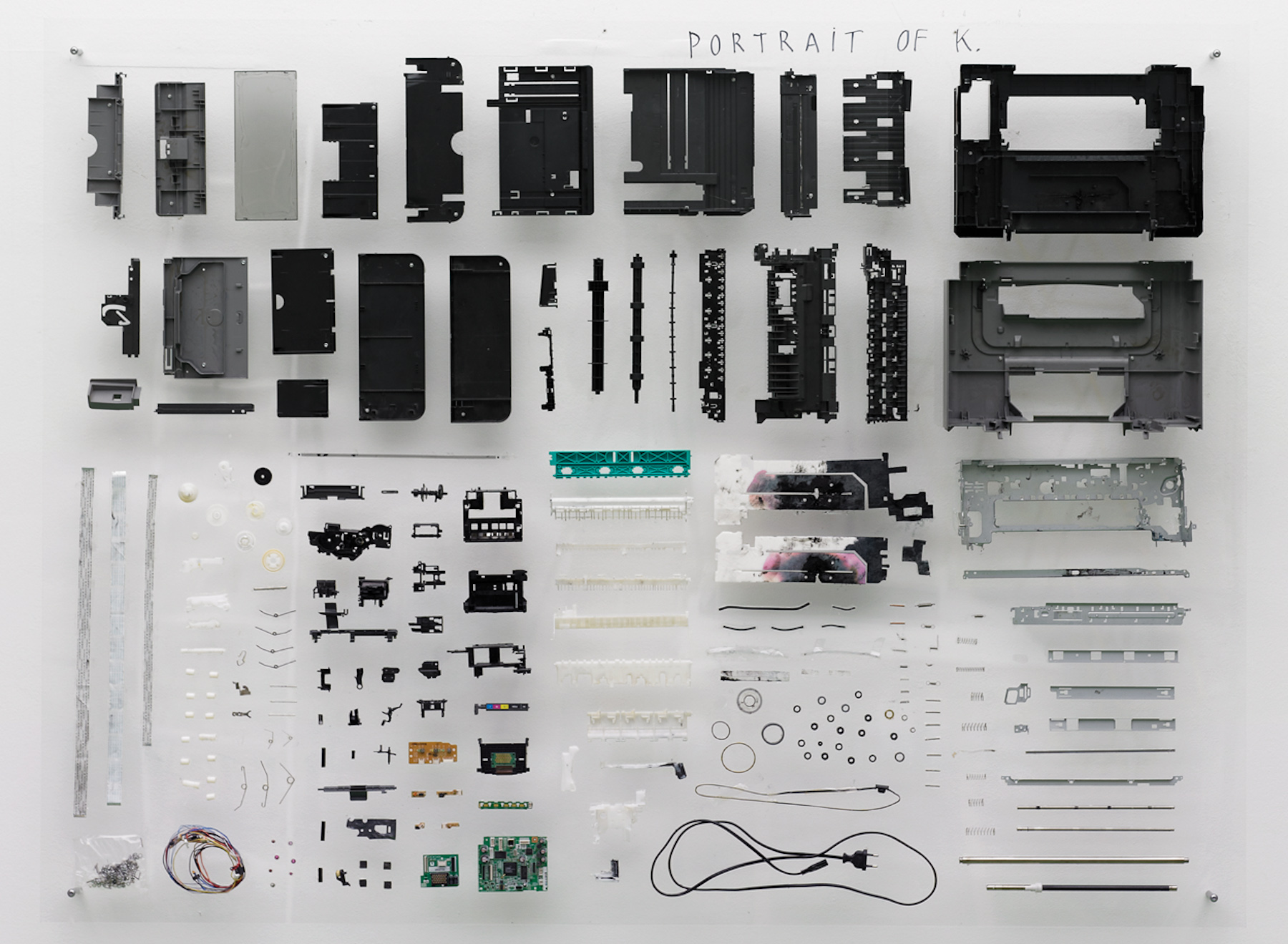

In Henrik Olesen’s I do not go to work today. I don’t think I go tomorrow. (all works, 2010), the situation is dire and persistent. Disassembled and attached to several hanging and wall-mounted acrylic and chipboard sheets are the components of various technological tools of production and reproduction. All the works in the series are titled I do not go to work today. I don’t think I go tomorrow., followed by the technical names of the apparatus: Canon K104389;12” PowerBook G4; Sharp DV-RW. Arranged in an anatomical logic, each machine is pulled apart neatly and laid out in a manner that allows you to comprehend how each component might fit with the next. Parts that were previously attached retain proximity in their flattened out display; the inert motherboard and her microchips float, wistfully detached from one another. From the looks of it, progress will not be made any time in the near future, much less tomorrow.

Henrik Olesen, I do not go to work today. I don’t think I go tomorrow. (Canon K104389), 2010. Printer, disassembled, mounted on plywood; 2 parts, 39 1⁄2 × 79 inches each. Courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne.

Henrik Olesen, Portrait of Kirsten / Canon PIXMA iP4200, 2011. Disassembled Canon PIXMA iP4200 photo printer mounted on Perspex, 79 × 59 inches. Courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne.

Apprehending all of these obsolete and dissected technological body parts is like contemplating a murder scene. I imagine the process of making/unmaking these pieces, screwdriver in hand, with the clear substrate laid down forensically, as if to catch all the evacuating fluids, the escaping life. The flowing blood of Aztec rituals has become invisible, replaced by ectoplasmic information pooling below each screw. Olesen delivers the ghost in the machine. The work’s title initially comes off as resigned, but with so many of these destroyed forms on display, agency and defiance cut through. Questions of labor jut out as in broken bones transgressing the boundary of the skin. How much labor was required to make each of these discrete units in the first place? Torn to pieces, we are left to imagine the distant sites each single object touched, now that their commodity status and usefulness has been stripped. Ultimately, it is now the work of art; we can anthropomorphize the printer: “She had so much potential. I thought we might have one more night together.”

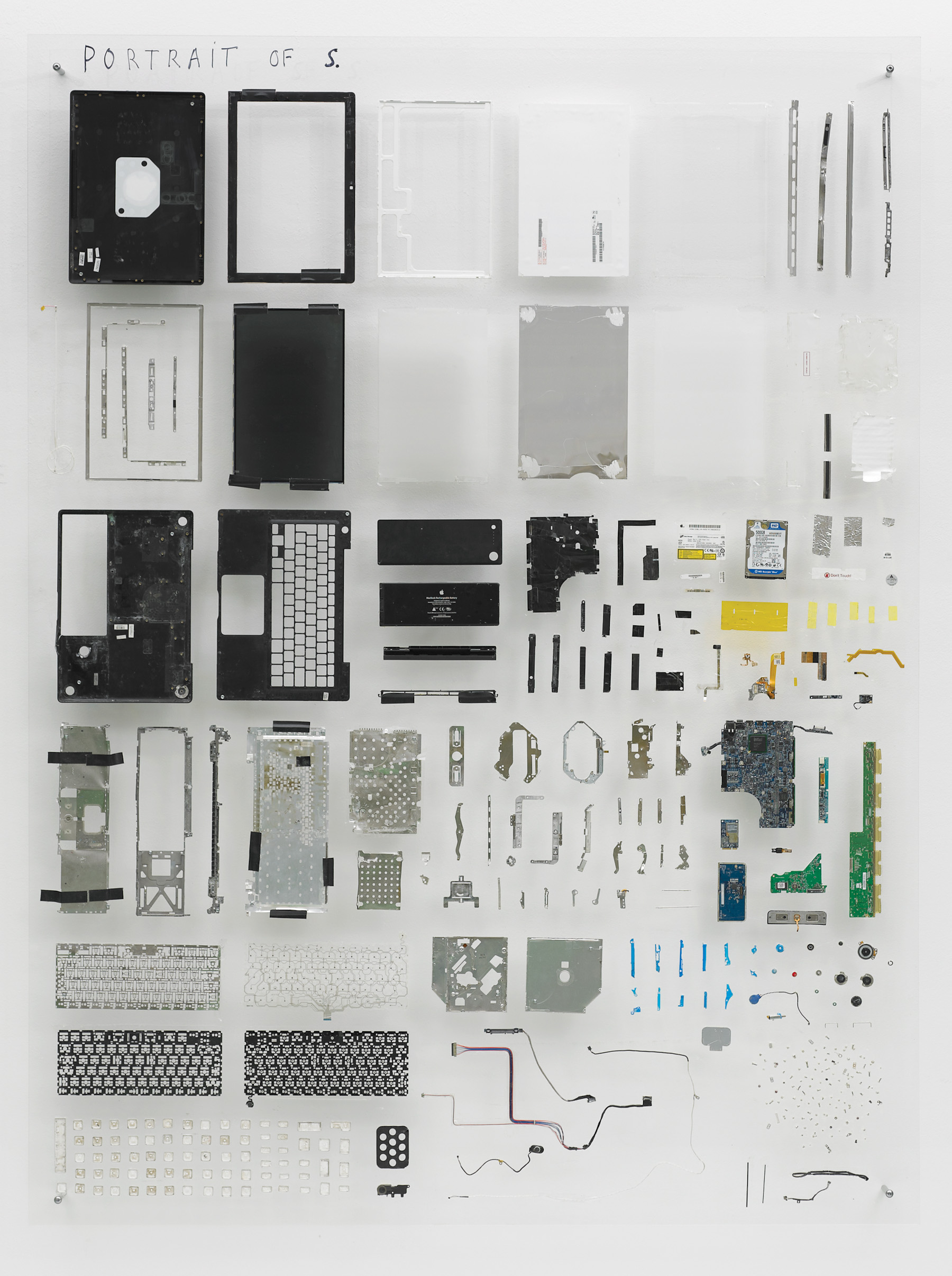

Olesen’s ongoing work has been engaged in thinking through the life and projects of Alan Turing. A significant contributor to the field of artificial intelligence, he created the Turing test, a game used to determine a computer’s ability to mimic humans.19 But it is Turing’s tragic history as a persecuted homosexual that has been key to Olesen’s analysis of hegemony and coded systems. This node of the artist’s practice comes through these works on a visceral level. For his 2011 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, Olesen made two “portraits” using the same technique as I do not go to work today. I don’t think I go tomorrow. These works, Portrait of Kirsten / Canon PIXMA iP4200 and Portrait of Scott / 12: PowerBook G4 (both 2011), suggest that Kirsten and Scott have also chosen to put down the mouse in solidarity with Olesen. As portraits, these devices stand in for and act in place of bodies marked by post-industrial immaterial labor, but it is the life force of the subjects being referenced. They operate as symbols invested through the economy of individual energies circulating in their respective social schemas and corresponding codes. The bare fragments are attached by various tapes and glues: artists’ tape, electrical tape, hot glue, and medical-looking adhesives. Certain small pieces are almost completely obscured by the method of attachment. They signal the atomization of life, but in antithesis, bring up the question of what this makes of subjectivity, for individuals and collectively. Acting as the temporary repository of a self that is generated by ones and zeros, this destruction on one level equals self-annihilation.

Henrik Olesen, Portrait of Scott / PowerBook G4, 2011. Disassembled 12-inch Apple PowerBook G4 laptop computer mounted on Perspex, 79 × 59 inches. Courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne.

These computers are sanctioned copies, made unique through use. Olesen takes the relatively accepted idea of the computer as a stand-in for a human to its extreme by eliminating the virtual realm and making the same assertion materially. He simultaneously skips, with a shortcut by screwdriver, to the tool’s planned obsolescence. The keyboard feels especially prescient. It represents the memory of touch, but all the keys are turned away, hiding their identity and the alphabet. The intricacy of these fragments of the device resonate in tandem with the hand’s carpals, metacarpals, and phalanges. This is the zone of transmission. And here we are with hands and eyes, but somehow without a body.

Connective Tissue

A deep pathos connects the works of Abaroa, Gaillard, and Olesen. Each of these artists grabs the baton of his self-selected forefather and runs with it, making his own monuments and memorials in the act of undoing the past. Technology forever lurches forward, continuing to automate tasks and drive efficiency; our computers start to feel more powerful than we are. If only Turing were with us today to help break the congealed codes presented by these three artists. It is substance, via the surrogate coming into its own, simultaneously acknowledging and tossing aside its history to find now through bodily paths of creation and destruction, that can do the work of unbinding. The destructive impulse has managed to restage these codes of interaction, perhaps to make a wedge into what is fused. These works all point beyond the crisis that began with the velocity of information before 2008 and the devalued post-breakdown subject that came after. The insistence of now in these works goes hand in hand with the speed of technology and a corresponding pain in the choked flows of desire and human contact. Abaroa pulls Paz into the present, Gaillard wrangles Smithson, and Olesen memorializes Turing. They are each connecting and insisting; this is the crux of the potential for the creative knife, carving and reworking constantly, with bold intent.

Brica Wilcox is an artist who lives and works in Los Angeles. She is a member of the collective D3, www.D-three.org, and is on the editorial board of X-TRA.