Provocative art historian Aby Warburg remarked in a notebook of 1928: “The creation and the enjoyment of art demand the viable fusion between two psychological attitudes which are normally mutually exclusive. A passionate surrender of the self leading to complete identification with the present—and a cool and detached serenity which belongs to the categorizing contemplation of things. The destiny of the artist can really be found at an equal distance between the chaos of suffering excitement and the balancing evaluation of the aesthetic attitude.” Chaos and cosmos: subjectivity and objectivity; seeing and reflecting; near and far. Warburg understood that chaos and cosmos must retain their proximity for the creation of art and for its enjoyment. Beginning with the premise that subjectivity and objectivity are interrelated, this column proposes a dive into the heart of the viewing experience of art, to that still point of uncertainty where the work of art and the beholder are held together in the space of the aesthetic, a space that encompasses chaos and cosmos. Art is a proposition wholly its own; works of art are theoretical on their own terms. At a time when artworks are increasingly marshaled toward the ends of meaning and the marketplace, this column might be regarded as its own form of political intervention.

Supposing another question than “Who speaks?” Umberto Eco asks, “Who dies?” “Who speaks?” bespeaks “the free man who can afford ‘contemplation.’” “Who dies?” is the slave’s question. “For the slave,” Eco explains, “the proximity of being is not the most radical kinship: the proximity of his own body and the bodies of others comes first.”1 “Who dies?” is an ontological question, a question about being, Eco insists. Yet this question about being never takes flight from the realm of matter since it is poised through the body of the slave. In this sense, the slave’s question differs categorically from the contemplation of the free man, whose freedom from his own body and the bodies of others allows him to sense the proximity of being and to carry out the purely mental operations that constitute philosophy.

Mimicking the philosopher, the free man asks, “What is being (What is death)?” Beginning from the proximity of his own body and the bodies of others, the slave asks, “Who dies?” In its particularity, the answer to this question is unphilosophical: “It is we who die.” As it shades onto ontology, the answer to this question is philosophical and it comes in the form of its own question: “Why do we die?” Considering the question “Who dies?” is to rest within and to rise above the body of the slave at one and the same time. It is to hear in the answer to that question, in that “we,” the slave and the human being, the particular and the general—and a particular that can never be subsumed into the general. “Who dies?” This is the question Library of Dust asks—of me.

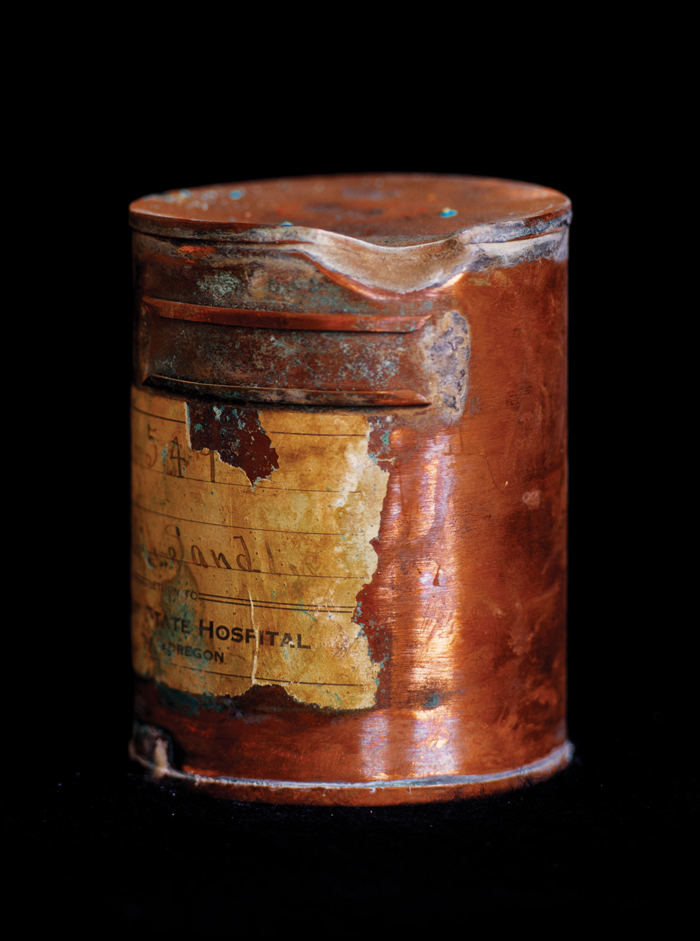

Library of Dust is comprised of 100 C-print photographs. These photographs are human scale. (They measure 64 x 48 inches.) Aligned along the wall, they confront me with their beauty, and their insistence. They depict a single subject: copper canisters containing the individual ashes (the dust) of mentally ill patients of Oregon State Hospital who were cremated, beginning in 1913, and unclaimed, since then. Placed in sealed copper canisters outfitted with a label and ID number, the ashes—of 5,121 individuals—were stored in canisters in the basement of hospital building number 40. In 1976, an underground memorial vault was created at the hospital. The canisters were moved there and interred on pine shelves. But the memorial vault, which suffered repeated flooding over a period of some 15 years, proved inhospitable. In 2000, the canisters were transferred again, this time to a storeroom near the crematorium on hospital grounds, the site where Maisel encountered them.2

Maisel photographed the individual canisters using a medium format camera. The medium format film (a 6 cm. x 8 cm. original) offered him a wealth of detail and the movements on the camera’s front element (where the lens is placed) allowed for perspectival correction. This camera enabled him to treat the canisters like architecture, that is, to photograph them accurately, without distortion or keystoning. At the same time, he captured them with a shallow depth of field. As a result, some parts of the image are in focus while others are not.3 To photograph the canisters, he placed them individually on a table draped in black felt. He covered a nearby window with a filtering material to soften the light; no additional light was added.

Rising to human scale, the individual canisters appear monumental in the photographs. Composed of a single subject, they are monolithic. Yet their subject is death, transformation, dissolution. Monumental and monolithic on the one hand, miniature (if measured against the scale of society’s monuments) and decomposing on the other hand, death rises in the observation of these canisters as an ontological and an individual question, as the question posed by slave. “Who dies?”

The contact of copper and water has transformed the canister’s surfaces voluptuously. These surfaces conjure real and imaginative worlds—the dust of galaxies, being under a microscope, the dazzling colors of the wide-open mind. The canister’s surfaces appear so, and they appear under duress. Transformed by time and fate, one might say, philosophically. Yet to say so would be to veer away from the obdurate individuality of the canisters, from their stubborn insistence, from the way they greet me as present and abiding, despite their magnificent duress.4

The voluptuousness of the canisters, of the photographs themselves, is shot through with unease. Voluptuous unease is here but a covering for a host of uncomfortable proximities—the proximity of the canisters’ machine-made uniformity and their individual patterns of corrosion and efflorescence; of the dead and the living; of the order, accumulation, and ever-nearing totality of the library and the disorder, accretion, and ever-molting divisibility of dust; of the body of ashes of one patient and the bodies of ashes of others. The dust of people, of people judged mentally ill. The unclaimed insane—a double indignity. Nonetheless, like the individuality of a fingerprint, the particular chemical composition of the ashes of each cremated body has cataylized its own reaction on the canister’s surface. Death, the great leveler, is here the beginning of a process of blooming individuality.

Until recently, photography has been addressed through formalist or postmodern approaches. In the late sixties and early seventies, art historians sought to define what distinguished photography from other media such as painting and drawing. Believing there was a separable thing called “photography” and that the meaning of the photograph resided in the medium and its formal features, they charted photography’s formal features for a new viewing audience for photography as art. Maisel’s photographs are art and they are so on account of their formal features. Their beauty, their framing, their vantage point, the crispness and subtlety of their detail, and the way their subject matter intersects with these formal features, make such a claim undeniable.

Around 1970, postmodern thinkers began to contest a formalist approach to photography, and they did so from a variety of theoretical vantage points, including Marxism, feminism, psychoanalysis, and semiotics. For all the differences in postmodernist criticism, it can be said that it converged around the idea that the meaning of photography lay in the field of its institutional spaces rather than in the photographic image itself. Photography’s history, in turn, was not to be found in photographs but in “the collective and multifarious history” of those “institutions and discourses” that constituted the photographic field.5

Considered in terms of their photographic field, the photographs comprising Library of Dust cannot be separated from a history of the practices of psychiatry and the asylum, or state hospital. Library of Dust’s photographic field is meaningful, and it lends these images a generous share of their unsettling power. “Who dies?” “The mentally ill.” “The unidentified.” “The unclaimed.” The death of the body (the mentally ill) comes before the dead body’s loss to history (the unidentified; the unclaimed). Those conferred with the knowledge to level the distinction “mentally ill” were granted the power to carry out the effects of that distinction.6 “It is we who die.”

I am drawn in by the beauty of these photographs; I am held and haunted by what they contain. In the space of the aesthetic experience, these responses cannot be told apart. My attentiveness is sensuous and mental, in and outside the photograph, formalist and postmodernist. I see and I reflect; I am subjective and objective. Meaning lies in the folds of the photographs’ voluptuous unease—by what is there; by what is no longer there; by what the photographs refer to and signify.

Allan Sekula has studied what he calls “the traffic in photographs.” “Taken literally, this traffic involves the social production, circulation and reception of photographs in a society based on commodity production and exchange. Taken metaphorically, the notion of traffic suggests that peculiar way in which photographic meaning—and the very discourse of photography—is characterized by an incessant oscillation between … objectivism and subjectivism.”7 The fate of those photographed is to be caught within this oscillation, a movement that makes of the so-called sitter an individual and a visual thing, a subject and “a commodified object-image equivalent to all others.”8

What Sekula calls photography’s twin ghosts—“the voice of a reifying technocratic objectivism and the redemptive voice of a liberal subjectivism”9—haunt the practice of looking, too. The aesthetic experience is, after all, an experience under capitalism, an experience that was codified alongside—but supposedly apart from—capitalism at the end of the eighteenth century. Oscillating between feeling and thought, imagination and reason, in the space of the aesthetic experience, my seeing becomes reflection—becomes, an object of thought. In the aesthetic experience, I photograph myself.

For Sekula, photographs are indexical signs before they are anything else. Linked “by a relation of physical causality or connection to” the subjects and objects they depict, as an index “the photograph is never itself but always, by its very nature, a tracing of something else.”10 Or somebody else. As looking closes the gap of time, I become aware of the proximity of my own body and the bodies of others who appear before me in these photographs as individual things. Subjects and objects.

Is it photography that has transformed these bodies into things? Or is it death? In these photographs, death is alive. Corrosion indicates decay but in its efflorescence, it signals a life force. In 1903, Alois Riegl coined the term “age-value” to account for decay’s simultaneous death and life. Decaying monuments, he wrote, “are nothing more than indispensable catalysts which trigger in the beholder a sense of the life cycle, of the emergence of the particular from the general and its gradual but inevitable dissolution back into the general.”11 “Who dies?” “I too will die.” Akin to the canisters’ corrosive beauty, the association between dissolution and our own fate might be voluptuous. Georges Bataille observed our obsession “with a primal continuity linking us with everything that is.” We “yearn” for this continuity, he held; it alone “is responsible” for human eroticism.12

But here death encompasses more than decay, more than my own dissolution, however voluptuous that imagined reunion. The photograph, whatever its subject, is also an index of time and history. Time and history lie between the photograph’s subject and the photograph itself. Time has opened her fan around some of the canister’s surfaces, covering them in a sensuous display of age value. Who the canisters contain is lost from view. Irrevocably. History as a story of the individuals contained inside these canisters is mute, dead in every sense.

If in the aesthetic experience looking closes the gap of time, meaning is never closed. Photographs, like works of art, resist our efforts to fix meaning through language. What distinguishes photographs, as works of art, lies not in the features of the medium (as the formalists would suppose) nor in the photographic field (as the postmodernists would have it), but in the resistance of the photograph to language. In Maisel’s Library of Dust this resistance lies in the folds of the photographs’ voluptuous unease, in the obdurate individuality of the canisters and their contents—and in this despite the consummate leveling effects of psychiatric diagnosis, confinement, cremation, and what Riegl called “age-value,” or the intertwined effects of time and natural decay. It lies in the proximity of my own body and the bodies of others and in the absent presence of those bodies. It lies in what might have been, in who might not have died, like this.

Karen Lang is a scholar in residence at the Getty Research Institute. She teaches art history at the University of Southern California.