He’s Coming to Trademark Your Cultura

Like, I suspect, just about every American child in my generation who grew up with access to a television, I came of age with Walt Disney, and the fictive Disney world came as near as possible to being “naturalized” as part of my own cultural experience. I never thought of the wonderful world of Disney as an instrument of an insidious cultural imperialism yoked to a neo-colonialist American foreign policy or as a graphic exemplar of capitalism’s necessary self-replication and its systematic attempts to co-opt and eviscerate an urban proletariat capable of confronting it with a socialist alternative. In the early 1970s, I visited the Magic Kingdom of Disneyland for the first time. During that same period, Salvador Allende’s short-lived Popular Unity government provided a brief but shining example of just such a revolutionary alternative. At the same time, the world Uncle Walt conjured into being starting in the late 1920s had become an increasingly central aspect of a much more global engagement with the endlessly expansive universe of American popular culture. I was thus primed for the experience of Jesse Lerner and Rubén Ortiz-Torres’s Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA exhibition How to Read El Pato Pascual: Disney’s Latin America and Latin America’s Disney, which arrived in Los Angeles just in time to serve as a background gloss for Disney’s latest “Latin American adventure,” the Day-of-the-Dead-themed animated feature Coco (2017).

The exhibition, which sprawled across two venues—the MAK Center at the Schindler House and the Luckman Fine Arts Complex at California State University, Los Angeles—was diffuse and to a certain extent disarticulated. Both the layout of the exhibition and the lack of a clear didactic support structure (such as wall labels) provided numerous interpretive puzzles for someone not privy to the expansive context provided by the essays in the accompanying exhibition catalog. In fairness, Disney’s absolute refusal to cooperate through the lending of archival and other materials clearly had a negative impact on the exhibition, placing Lerner and Ortiz-Torres in an almost untenable position, and it also impinged on the visual effectiveness of the catalog. Though not entirely successful, I commend Lerner and Ortiz-Torres for undertaking to present a rich and very complex artistic, political, and ideological picture.

One thing the exhibition makes absolutely clear is the facility with which Latin American artists working over the past several decades have seized an ever-expanding array of appropriative and other identifiably post-modern visual strategies (most importantly, perhaps, ironic inversion and re-contextualization) to repurpose the dominant culture to their own critical, revolutionary, and (increasingly) commercial ends, even as the digital revolution has driven an inexorable globalization of an increasingly heterogeneous cultural landscape.

To take one apparently straightforward example: Lalo Alcaraz’s marker on paper panel Migra Mouse (border patrol Mickey) (1994), where a jauntily posed Mickey practically fills the whole frame of what might almost be an old-fashioned Disney comic book.1 With twinkling eyes, trademark smile, and white-gloved hand on hip, Mickey (dressed à la Disney as a US Immigration and Naturalization Service agent) directs an assumed crowd of unseen migrantes toward a path marked “Mexico,” as if to say: “Hey, kids, the border is a door that only works in one direction.” It is resolutely closed to migrantes heading north, but swings easily the other way to facilitate the flow of all things Disney to the south. And, mirabile dictu, it is Disney “himself” (or at least his corporate avatar) who controls the operating mechanism. At the time that Migra Mickey was originally produced, its ironic meaning was pretty straightforward; but the subsequent history of Alcaraz and Disney provides the image with an interesting and complicating sub-text. When Disney was in the preliminary stages of preparations for Coco, the corporation, always alive to the maximization of merchandising possibilities, attempted to trademark the phrase “Day of the Dead.” The strategy backfired badly, in a controversy fueled least in part by Alcaraz’s sharply critical poster for the imaginary Disney film Muerto Mouse: It’s Coming to Trademark Your Cultura. In an interesting twist Pixar, the Disney subsidiary producing Coco, hired Alcaraz to serve as a kind of cultural sensitivity advisor on the film.

How to Read El Pato Pascual: Disney’s Latin America and Latin America’s Disney, installation view, Luckman Fine Arts Complex, California State University, Los Angeles, September 9, 2017–January 14, 2018. Courtesy of MAK Center. Photo: Michael Underwood.

Among the most iconic of all Disney themes is the princess in peril, saved from a terrible fate at the last moment by her dashing and handsome Prince Charming. To be fair, the idea of a “prince charming” (which must have roots as far back as medieval tales of chivalric love) is hardly Disney’s own invention. But the precise term does not originally appear in the canonical fairy tales with which Disney has made it forever associated (“Snow White” and “Sleeping Beauty,” for example). The theme of the imperiled princess and her heroic prince, which stretches from the animated Snow White (1937), still arguably the greatest Disney animation) to the live-action Cinderella (2015, starring Lily James), has virtually sparked a culture war all on its own. The feminist critique of the princess ideal should be so obvious as to need no recapitulation, likewise the status of the classic Disney princesses as icons of white European perfection. In How to Read El Pato Pascual, José Rodolfo Loaiza Ontiveros’s vividly colored canvas Black Dove (2014) neatly inverts the flow of cultural power, literally under the sign of el corazón (the heart pierced by the deadly arrow of love). In the painting, Frida Kahlo, herself a cultural paragon of considerable standing, drinks a trio of iconic Disney princesses (Snow White, Belle of Beauty and the Beast, and Cinderella) under the proverbial table.

The irony here is especially sharp since it has a political dimension. Although both Kahlo and her longtime partner Diego Rivera were staunch leftists and champions of indigenous Mexican culture, Rivera was also much taken with Disney animation. In 1931, probably under the influence of the Russian Revolutionary director Sergei Eisenstein, Rivera opined that, after the success of world revolution had swept away the need for a genuinely revolutionary art (presumably including his own heroic murals), “the aesthetics of that day will find that MICKEY MOUSE was one of the genuine heroes of American Art in the first half of the 20th century.”2 All caps in the original. As it happens, of course, world revolution has yet to take place, and Rivera’s embrace of “the [ubiquitous] Mouse,” both as a cartoon character and as a cultural icon, has been bitterly vilified, while the work of his wife, Frida Kahlo, has attained venerated status. Kahlo herself has come to be revered as a disabled woman speaking on behalf of La Raza, feminism, anti-colonialism, liberation politics, emancipatory art, and a general “queering” of normative or canonical culture.

Para Leer al Pato Donald

At least in a theoretical sense, ground zero of Lerner and Ortiz-Torres’s undertaking is the republication within the exhibition catalog of Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart’s short book, Para Leer al Pato Donald. Originally published in Chile in 1971, the book was reprinted in 1973 in a superb English translation by UCLA’s David Kunzle as How to Read Donald Duck: Imperialist Dogma in the Disney Comic. Both versions were long suppressed and/or out of print.3. The introduction by David Kunzle (Lerner and Ortiz-Torres, 194–207) provides essential background information on the ins-and-outs of Disney’s comic-book publication and also an essential supplement to Dorfman and Mattelart’s argument. Indeed, it is a most valuable piece of historical criticism in its own right, and can usefully inform reflection on any aspect of the How to Read El Pato Pascual exhibition. In and of itself, this republication of Kunzle’s translation, which appears along with some further authorial reflections by Ariel Dorfman and a brilliant introduction written by Kunzle in 1991, is worth the price of the catalog. It is a major piece of detailed and carefully articulated Marxist criticism of popular culture, published in the midst of revolutionary and counter-revolutionary upheaval. It belongs in your library. Both Dorfman and Mattelart developed their critique while working to seize and remold the means of cultural production (“the words with which we were speaking reality, the dreams with which we were dreaming reality”) from within the revolutionary Chilean regime.4 Thus, their text can use-fully be seen in relation to other, and earlier, Marxist evaluations of Disney, which often derive from a theoretical rather than a practical position.5

José Rodolfo Loaiza Ontiveros, Black Dove, 2014. Oil on canvas board, 16 x 20 in. © José Rodolfo Loaiza Ontiveros. Courtesy of Karen Hernandez and Brian Hill.

Walter Benjamin, for example, was much taken with Disney’s early free-wheeling “Steamboat Willy” style of animation, which he saw as anarchic and emancipatory: the work is simple (but not simplistic), direct, and a transparent celebration of an emergent mass technology. This seems also to have been the case with Sergei Eisenstein, who brought Disney’s animated short “Three Little Pigs” (1933) to the first post-Revolutionary film festival, but whose unfinished theoretical writings on Disney remained uncollected and unpublished in English until the late 1980s.6 Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno (Marxist philosophers and critics, and founding figures of the so-called Frankfurt School of cultural studies), writing rather later during the elaboration of the “classic” style of Disney animation and after the entire Disney enterprise had become a full-fledged addition to “the culture industry,” saw the animated shorts and features as exemplary of Enlightenment’s tendency (per their Dialectic of Enlightenment) toward the “mass deception” that marked their function as strictly ideological.

Although Dorfman and Mattelart’s argument is motivated by the prevalence of Disney-themed comics in the Chilean children’s literature market of the early 1970s, it is hardly a simple rant against the strong-arm marketing tactics that flooded the world with Mouse and Duck merchandise.7 Nor is their argument primarily a critique of the racial and ethnic stereotyping that has been an ongoing problem for Disney—and American popular culture as a whole.

This latter line of criticism is pursued by Darlene J. Sadlier in her meticulous essay in the exhibition catalog, which also describes a long entanglement between Disney’s entertainment enterprise and American foreign policy. This collaboration stretches from Disney’s work as a propagandist during World War II through the government’s implementation of the hemispheric postwar “good neighbor” policy, in which the studio actively colluded. While Mickey and Donald were definitely anti-fascists (and in fact, despised by the Nazis) during World War II,8 their cultural politics veered rightward as the Cold War unfolded. And while they worked to implement American foreign policy, their animation and live-action efforts promulgated exactly the stereotypical and neo-colonial vision of Latin America that eventually made that policy so ineffective.9

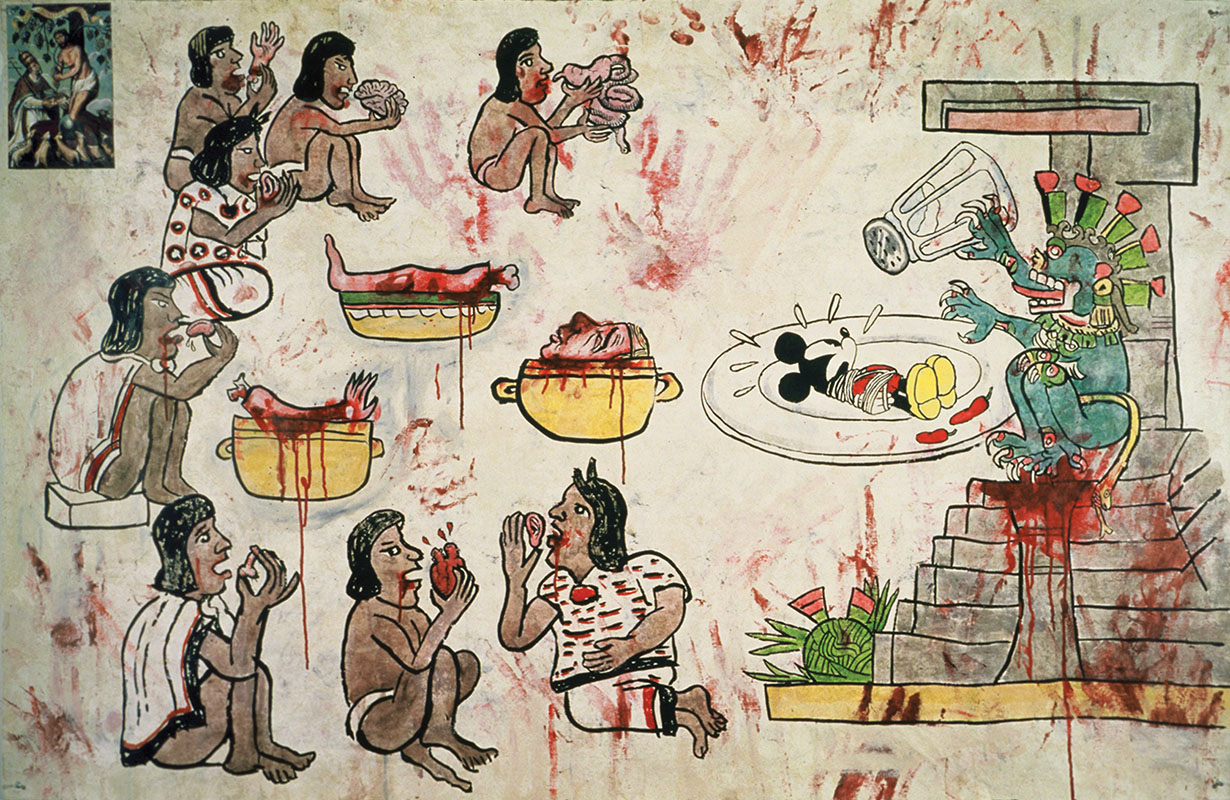

Enrique Chagoya, The Governor’s Nightmare, 1994. Acrylic and water-based oil on Amate paper, 48 x 72 in. Courtesy of MAK Center.

In Para Leer al Pato Donald, by contrast, Dorfman and Mattelart attempt to show how the relations of production characteristic of globalized industrial and financial capitalism (personified by the almost impossibly wealthy Disney character Scrooge McDuck) are reproduced in the Duckburg tales, from, inter alia, Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories (an ongoing series that has been published since 1940). Indeed, the authors attempt to lay out exactly how those relations function to structure everything we see and read. In an interesting crypto-Freudian twist, Dorfman and Mattelart’s analysis of this structure includes even the curiously asexual genealogical connections characteristic of nearly all the characters. Donald and Daisy, as well as the nephews Huey, Dewey, and Louie (not to mention Mickey and Minnie, the villainous Beagle Boys, etc.) live in a world of eternal courtship never consummated in marriage and/or procreative sex, where (with a single paramount exception) there are only uncles, aunts, nephews and nieces, and sets of brothers and sets of sisters. In a complex and provocative argument, Dorfman and Mattelart lay out a “dialectic of paternal power” in a world literally bereft of fathers and mothers.10

But the authors subject not just the bizarre particulars of Duckburg family life to scrutiny and critique. Plot, characterization, political and human geography, the replacement of “labor” with “adventure,” the effacement of any trace of the means or processes of production, the absolute fetishization of money as gold: all of these and more are dissected under the Marxist lens of Dorfman and Mattelart’s microscope. They note, for example, that Donald Duck is always both dead broke and well supplied with money (as the story’s circumstances demand), and never has a “productive” job of any sort. When he works at all, it is mostly as a low-paid gofer for his Uncle Scrooge McDuck. More frequently, he and his nephews are off on adventures to places like “Faroffistan” and “Outer Congolia” where, at their uncle’s behest, their mission usually involves obtaining some relic or artifact, the value of which almost without exception derives from the fact that it is made of gold, Scrooge’s “gold standard” for measuring value.11 There is never a factory, nor any other actually “productive” enterprise to be seen in Duckburg. As if by magic (or by Communism!), characters just seem to have whatever it is that they need. Dorfman and Mattelart’s extraordinarily close and careful Marxist reading of one hundred of Disney’s hugely popular Duckburg comics is contextualized with respect to a very specific time and place: revolutionary Chile—a “fat little [interpretive] worm” or a “tasty [hermeneutic] morsel,” as the wicked vultures Marx and Hegel exclaim in an exciting sequence found in one of the illustrations to the original English edition of How to Read Donald Duck that is reprinted in the catalog.12

Dorfman and Mattelart’s analysis can be mobilized to serve a number of complementary functions. It can serve as a template for the analysis of other examples of pop-cultural production. It also can provide a historical pivot around which to organize a more expansive look at both Disney’s well-nigh universally hegemonic cultural machinery and the response of Marxist artists and cultural critics to that machinery, especially as regards the technical and ideological evolution of animation.

How to Read El Pato Pascual: Disney’s Latin America and Latin America’s Disney, installation view, MAK Center for Art and Architecture, West Hollywood, September 9, 2017–January 14, 2018. Courtesy of MAK Center. Photo: Joshua White Photography.

Brilliantly incisive as Dorfman and Mattelart’s dissection of the Duck Tales stories is, it does not account for the complex case of the series’ author, Carl Barks (1901–2000). Barks was one of the most eccentric creators in the stable of talent at Disney, at least while Walt Disney was still alive.13 As was the case with another of America’s greatest twentieth-century cartoonists, Walt Kelly (the creator of Pogo Possum and the other animal denizens of the Okefenokee Swamp), Barks honed the skills essential to his later career at Disney’s animation studio in Burbank. He survived the divisive strike of animators and “in-betweeners”14 that roiled the studio in 1941 (and served to reinforce Disney’s own right-wing political views).15 In the wake of the labor unrest, he left Disney, only to come back later to work off the studio lot as a comic book writer and illustrator, creating the notoriously predatory capitalist Scrooge McDuck and (eventually) the entire Duckburg saga.16 Despite Barks’s own conservative politics and cultural preferences, the humor in his Duckburg stories often seems to undercut those same values, social and cultural institutions, and hidden modes and processes of production that Dorfman and Mattelart argue they embody. They fairly reek of satire and thus function simultaneously as affirmation and critique.17As invoked by the republication of Para Leer al Pato Donald in the exhibition catalog, the Barks conundrum is essentially an historical one. However, much of the art in the exhibition serves not simply to illustrate history, at least not straightforwardly, but rather to illuminate Ariel Dorfman’s on explicitly expressed regret in reconsidering the meaning and importance of his critique of El Pato Donald: “I think I exaggerated how much it [the Disney cultural juggernaut] conquered Chile… [Para Leer al Pato Donald] doesn’t give enough credit to the capacity of the people to reinvent Donald Duck for themselves.”18

Revisionist History

When Dorfman and Mattelart were writing, the Disney Empire may have seemed insurmountably imposing. Now that Disney has acquired Pixar Animation (at one time a serious rival spun off from Lucasfilm Ltd. and funded by Apple), as well as Lucasfilm itself and most recently (if all goes in their favor) the entertainment assets of 21st Century Fox, it surely has morphed into an entertainment Leviathan of almost incomprehensible power and reach. Relentless and insidious, Disney’s cultural hegemony spreads outward across an ever-expanding terrain, even as it seeps into the ground of history, adumbrating its eventual triumph. In How to Read el Pato Pascual, Meyer Vaisman’s alterations in paint and embroidery to a reproduction of a French Renaissance tapestry (Untitled, 1981), exemplify the corporation’s march across the globe. A “well-armed” Mickey and friends stride and crawl bravely alongside an anonymous military company comprising a mounted swordsman, a harquebusier, and a standard bearer. The work is large, roughly five by six feet, and rather imposing. But the figures in the original tapestry are awkwardly conceived and the setting, except for some lovely foreground flowers, is minimal and difficult to interpret. Thus, the inserted figures (especially Mickey brandishing his umbrella) are curiously more naturalistic and (as projections onto the screen of the tapestry) appear more alive than the depictions of the humans whose world they have infiltrated. It is as if contemporary animated culture has shown itself superior to the handcrafted culture of the past. It is certainly more familiar.

Meyer Vaisman, Untitled, 1981. Embroidery and paint on reproduction of French antique tapestry,

55 x 67 in. Courtesy of MAK Center.

In several other works on view, a ghostly army of sinister Disney specters infiltrates the nineteenth century, spreading like a transmogrifying virus through scenes “commemorating” key events from America’s War with Mexico (1846–48), a war that itself defines a deeply contested historical moment in America’s Manifest(ly) (imperialist) Destiny. Works by Demián Flores, for example The Storming of Chapultepec or The Capture of Monterrey (2011), render the Disney presence especially malignant and frightening. Each of the five works by Flores (which I assume constitute a series) illustrated in the catalog is described as “intervened Facsimile, collage, gouache, and watercolor.” The artist has inserted collaged figures retouched with gouache and watercolor, which sometimes loom over the battle fields and sometimes insinuate themselves into the heart of the action. These interventions are not precisely subtle, but they are so well integrated into the original “facsimiles” that the results are chillingly effective.19

Demián Flores, Battle of Molino de Ret, 2011. Intervened Facsimile, collage, gouache and watercolor, 17 3⁄4 × 23 3⁄4 in. © Demián Flores.

Almost equally unsettling are two of Enrique Chagoya’s insertions of Disney characters into copies of Francisco Goya’s notoriously dark print series Los Caprichos (1797–98) and Los Disastres de la Guerra (Disasters of war, 1810–20). In Liberty (2006), from the Los Caprichos series, the lovable yet aptly named Dopey, from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), vacuously regards the body of a man hanged from a branch on a war-shattered tree. In Homage to Goya, Disaster of War #9 (1983–90), from Disastres de la Guerra, Mickey is an interior observer in a refiguration of Goya’s famous Grande hazaña! Con muertos! (A great feat! With dead men!). Here, the mouse cheerfully urges us to regard three naked corpses, all castrated and bound up to a similar stump, one having suffered the added indignity of decapitation and further mutilation.

This association between Disney and violence, both personal and institutional, continues in Augustin Sabella’s Disneylandia (2010). Painted on an album cover, the word Disneyland, in the corporation’s characteristic script in vibrating red and blue, dominates the top third of the image. Below, an enormous, gun-toting Mickey presides over Cali, Colombia, home of one of Latin America’s most notorious drug cartels. In Mickey (2003), Dr. Lakra transforms a found Mickey Mouse toy into a tattooed, gun-toting gangster caught with his pants literally down. “Dr. Lakra” is the pseudonym of a Oaxacan tattoo artist who applies his stylus to a wide variety of mediums in addition to human skin. Here, the artist inks images and words that evoke the barrio and its seemingly omnipresent street gangs. The bandana wound around Mickey’s head and the grossly out-of-scale toy pistol complete the picture of innocence corrupted and pledged to the twin divinities of sex and death: Live Fast, Die Young!

Robert Yager’s searing black-and-white photograph Crack-Cocaine and Cash (1994) shows an infant sleeping alongside a plush Mickey and other toys on a bed surrounded by bullets, guns, and the cash and drugs referred to in the title.20 The photograph provides a dark commentary on the complex cultural entanglement of Disney and Latin America. Crack-Cocaine and Cash is accompanied in the exhibition by Toon Town (1993), which shows a tight crowd of children and their apparent gangster fathers, one of whom brandishes a sinister-looking blade, clustered around Roger Rabbit at Disneyland. Both works take us inside the world of Los Angeles street gangs that Yager chronicled in his award-winning photo-essay Playboys.21 Beyond the poignancy embedded in the juxtaposition of childhood innocence with a culture saturated with drugs and violence, we can see the image of an endless circulation of drugs, cash, violence, vast cartels, local street gangs, even individual gangsters across the border so assiduously (yet apparently fruitlessly) guarded by Border Patrol Mickey. And if Disney culture—legal and superficially benign yet insidiously corrosive—is one of the United States’ main exports to Mexico and other Latin American countries, another of those exports—this one illicit and explicitly deadly—is guns.22

Dr. Lakra, Mickey, 2003. Found toy and mixed media, 10 3⁄4 x 3 1⁄4 x 2 in. © Dr. Lakra. Courtesy of Vanessa Bransen.

El Pato Pascual and the republic of Children

Because the exhibition is so expansive in its scope, it is simply not possible to address all the relevant issues, or even all the most important themes, in the space allotted here. For example, the exhibition devotes a section to documenting the amazing (and to me quite new) story of Argentina’s counter-Disneyland, La Rebublica de los Niños (The Republic of Children). An apparent ideological reversal of the idea behind Disneyland—which sought to create a homogenous “magic kingdom” completely shut off from the outside world—the theme park in Buenos Aires was conceived “during Juan Domingo Perón’s presidency and the glorification of his wife Evita” as “a public recreation and civic education center for the children of working families.”23 Like Disneyland, the Republic of Children is dominated by a fairy-tale castle, but the latter predates Disney’s original Anaheim theme park by several years.

Daniel Santoro’s Winter at the Republic of Children (2012), was evidently conceived as a commemoration of the death of Eva Perón. The painting, in oil and acrylic, provides a stark testimony to a fairy-tale ideology plunged into an endless winter by the death of the princess. I am reminded of the eternal winter of C. S. Lewis’s children’s book The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (1950), although the two white-clad children with black mourning bands resonate as a doomed Hansel and Gretel just entering the witch’s woods. Yet perhaps the princess is not in fact dead, as Santoro suggests in his amazing recapitulation of “Sleeping Beauty,” Eva Perón Conceives The Republic of Children (2002), which also suggests the display of the body of the dead Lenin, as well as evoking the architectural framework of Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper.

Another thread in the exhibition concerns the ongoing dispute behind the character El Pato Pascual—a corporate logo bearing an uncanny resemblance to a certain Duckburg resident. This story involves Disney’s relentless legal maneuvers aimed at promoting its own intellectual property rights (suing for violations of copyright or trademark) despite the fact that the company involved, the iconic Mexican soft-drink and juice manufacturer Refrescos Pascual (sometimes also referred to as Pascual Boing after the name of its most popular brand), had originally appropriated Donald via a valid licensing agreement in the 1940s. At the same time that the Refrescos Pascual corporation was embroiled with Disney over the licensing issue, its ongoing dispute with workers over low wages, denial of overtime in violation of Mexican labor law, and attitude of paternalism, among other factors, led to a strike in May 1982 that dragged on for three years. Eventually, the owner filed for bankruptcy and the workers formed a collective that took over management and production. This long and bitter dispute is chronicled in the exhibition in Carlos Mendoza’s Super-8 activist video, Pascual, la Guerra del pato (Pascual, The War of the Duck, 1986).24 Although in the present context the 1982 Pascual strike might recall the divisive animators’ strike against the Disney studio, in 1941, the outcome was completely different. As described at the time by the Marxist journalist Fernando Buen Abad Domínguez, the triumph of the proletariat at Pascual rendered their whole enterprise “intolerable for a parasitic bourgeoisie, unacceptable for a parasitic bureaucracy, and unforgivable for a parasitic sectarianism.”25 Yet, as the artworks in the How to Read El Pato Pascual exhibition demonstrate on numerous occasions, the doctrinaire Marxism deployed by writers such as Dorfman and Mattelart has been abandoned by cultural producers today, who favor a much more free-wheeling postmodernism. In the case of the Pascual cooperative, the logo character has been redesigned in an explicitly hip-hop vein as Pato Cholo (Cholo Duck).26 In a commercial on view in the exhibition, Cholo Duck seems quite at ease dancing Gangnam style in front of the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico City, with two heavily made-up young women in tight mini-skirts. Lerner maintains that Eisenstein would have been proud. I’m not so sure.27

Disney in Deep Time

I would like to end with what seems to me one of the triumphs of the show: Nadín Ospina’s faux artifactual evocations of a lost Disney civilization. For example, her Hallowed Siamese Twins (2001), a delicate sculpture of gold-plated silver, might almost rival the work of the Aztecs, the Mayas, and the Incas, although the mythology of the twins’ smiling Mickey Mouse heads will not be covered in any handbook of Mesoamerican art or culture.

Daniel Santoro, Winter at the Republic of Children, 2012. Oil and acrylic, 39 1⁄4 x 55 in. Courtesy of MAK Center.

Enrique Chagoya’s The Governor’s Nightmare (1994) similarly summons up an imaginary pre-1492 Mesoamerican world. Chagoya’s painting on paper brilliantly conjures that world via a faux post-conquest codex that illustrates a bloody cannibalistic sacrifice in which Mickey himself is trussed up as a treat for a horrific deity who sits quite literally on a throne of blood: the conquered “natives” recall their own indigenous history as a quasi-mythical ritual offering up of the remains of their massacred conquerors.28 In contrast, Ospina reverses that entire history and sinks Mickey and friends into deep Mesoamerican time, where, no longer signifiers of conquest, they might resonate more easily with Jung’s theory of archetypes or Sergei Eisenstein’s notions regarding the deep totemic roots of Disney’s anthropomorphic animals than with the idols of cultural imperialism and globalized corporate capitalism.29 In essence, Ospina’s (re)constructed civilization depends on an actual artifact: a zoomorphic ceramic pot that evokes the shape of a duck and can be dated c. 300–700 C.E.30 It might almost be labeled: “Donald Duck (very early concept art),” and it provides Ospina with a marvelous taking-off point, most closely for her Three-legged Zoomorphic Plate (2001), an aged-looking bowl supported by three feet in the shape of duck’s heads that resemble Donald. Ospina’s plate is embedded in the artist’s extensive production in ceramic, stone, and gold-plated silver of a wide variety of artifacts: domestic (including the marvelous Erotic Drinking Cup with a quite engorged and obviously enraptured Mickey, 2009), architectural, and religious. Her works in the exhibition include a ritual ceramic vessel crowned by a shamanic Donald (Vessel with Shaman, 2001) and a small, elegantly detailed altar of carved stone that honors Goofy as the God of Hallucinogens (2001).31

Nadín Ospina, Hallowed Siamese Twins, 2001. Gold plated silver, 4 3⁄4 × 4 × 1 1⁄4 in. © Nadím Ospina.

Ospina’s work draws on both anthropology and ethnography, as well as notions of primitivism in belief and primitive power in art—all intensely contested ideas and disciplines—in a discussion that is already complex and multivalent. There seems little question that contemporary “Disney culture” is one of the major drivers (although there are certainly others) at work in the ongoing creation of a global culture. It is easy to imagine a distant future in which, like Ospina’s objects, culture will speak to our descendants across the expanse of deep cultural time a message that is heterogeneous, conflicted, and difficult to understand. But that, it seems to me, is how culture inevitably works. It can indeed aspire to greater and greater hegemony, but as long as there remain artists like Ospina and the others represented in this exhibition—not to mention critics such as Dorfman and Mattelart—that hegemony will remain only a grim façade, or, perhaps better, an appearance of death evoked by a wicked spell and spread by the voluptuous beauty of a bright red apple, but easily dissolved by true love’s kiss.

Glenn Harcourt has a PhD in art history from the University of California, Berkeley. He lives in Pasadena and writes on various aspects of the history of art and culture. His most recent book is The Artist, the Censor, and the Nude: A Tale of Morality and Appropriation (Los Angeles: DoppelHouse Press, 2017).