Even before the term identity-politics came into use, there were those who engaged in a political thought process based in identity. These individuals critiqued not only mainstream culture and society, but the ways in which they believed the left had overlooked the significance of race, gender and sexuality in favor of perspectives it deemed more foundational, such as class, economic structure and later philosophical questions of meaning in form. Frantz Fanon, Ralph Ellison and Simone de Beauvoir were but a few writers who directly criticized the left, pointing out perspectives overlooked in the discourse of social equality and fair distribution of resources. Those who took up the cause of critique from the standpoint of identity had a major task. They were charged with informing the world of leftist thought– both in the academy and in the arts–of the urgency to address race, gender and sexuality. Moreover, they had to exhibit the ways in which these critical perspectives could illuminate omissions within the accepted discourses of social and political justice and their cultural manifestations.1

Since the 1970s, artists have been invoking critical politics of identity to analyze the vocabulary of socially conscious art. Understanding that oppression is folded into the same language that renders identity, these artists sought, and still seek, not to portray subjectivity, but rather to analyze its function in the expansive field of art. Their artworks delineate identity as a subset of subjectivity, that part of the subject identified with a larger social group through representation, in its widest possible definition. The artwork thus becomes a lens, bringing into focus the function of identity in social interaction within the art world as a public sphere. Art is assumed by these artists to be a discipline of critical practice. Aimed internally within the left, this intervention stimulates a methodological debate about political art. I argue that this lineage of practice affected, and is continuing to negotiate, one of the most significant contributions to contemporary critical art.

Critical identity politics became increasingly significant as art expanded into an interdisciplinary model influenced by fields varying from philosophy to psychoanalysis, or the praxis of political activism. Artists such as David Hammons, Mary Kelly, and Jimmie Durham (to name a few) developed a conceptual approach to art in part to affect critique of assumptions and methodologies of a left-leaning art world as questions of art’s methods, status and means of circulation came into focus.2 for numerous artists today who cite Minimalism, Conceptual Art, and institutional critique, the weight of critical identity politics is sustained as a key analytical method. Adrian Piper, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, and Kori Newkirk are artists who have over the years utilized identity as a social category that overlaps the personal, but who have not sought to merely represent it. In the following pages, I trace their trajectory as an example of one arc within a broader movement of critical identity politics.

Paradoxes–often the subject matter of conceptualism –were for Adrian Piper a lived experience. Isolating experience, especially the oppression of racism, her work suspended it between autobiography and fiction. Piper’s work became a model for conceptual practice that did not presuppose neutrality or objectivity, thus posing an active critique of the assumptions of Conceptual Art. Felix Gonzalez-Torres integrated conceptual practice and the influence of critical feminism into the strategies of political art by insisting on the particularity of identity as subject matter. Following this lineage, which defines identity through the analysis of its construction, Kori Newkirk returns to imaging the figure in order to examine its place within the matrix of signification in which we live. for these artists, the nature of identity was–and is–understood as paradoxical, not rested upon as given.

The following case studies are not meant to privilege these artists over others for whom issues of identity inform a significant part of their practice. My choices highlight the inter-influence between sets of social and personal identifications, all of which are based in identity but not the same “kind” of identity. Instead, I look at identity as the part of the subject that functions within the social matrix of representation.3 The three artists chosen represent a range of demographics as well as artistic attitudes. They stand as examples for an important development in the use of identity politics as a critical perspective in and on art, a practice that is also concerned with an analysis of the ways art makes meaning. I wish to show how the uses of identity as a political perspective drives a methodological investigation into art making. The result is a front of artistic production–a critical approach to identity politics based in analysis of visual and textual language within the social and cultural field.

Adrian Piper: The Paradox of Identity Politics

Adrian Piper works between two kinds of autobiography –the self as a lived entity (an experience) and the self as a literary function (a character). In her work, Piper identifies an inherent paradox within identity politics, where designations of sexual, racial or gender identity utilize the very terms of discrimination in the articulation of self-definition. Since the late 1960s, her work has underscored not only how identity comes to be constructed from multiple conditions that pre-exist one as subject, but also how the sense of self comes to be shaped through verbal and visual language and is therefore subject to constant negotiations. Repeatedly, she has posed questions of existence, fragmenting notions of being to the point of self-obliteration. Many works enact a delicate balance between conceptual practice reliant on analytic thinking and critical analysis of that way of thinking.

As a first-generation Conceptual Artist, Adrian Piper operated in the aesthetic and methodological paradigm of a movement that, for the most part, intended to dismantle the idea of transcendental visual experience, the role of art as a bourgeois commodity, and thusly art’s means of distribution.4 Creating an intersection where race, class and gender function in definitions of identity, Piper analyzed multiple assumptions that sustained structures central to the art world at large and to Conceptual Art in particular. Broadly speaking, conceptualism relied upon, or was in dialogue with, notions of reason, emotional distance, and objectivity. Within this context, Piper’s cultural analysis based in the politics of identity was exceptionally effective and has remained exceedingly influential. Activated in sites where racist oppression embedded in language is manifested daily, her practice unpacked the operations of social and cultural systems in the realm of the personal.

Several series of private and public performances positioned Piper as both an insider and an outsider in the New York avant-garde art world of the 1970s. As an “outsider” in terms of class, race, and gender, she identified invisible assumptions created and exercised by an art world blind to exclusions sustained by its structure and vocabulary. Yet by exposing flaws in discourse informed by continental philosophy and Marxist dialogue (both operating as if their critical apparatuses covered all aspects of social justice), Piper imperiled the very structures that kept her subjectivity intact.

Piper’s artwork and writing of the period demonstrated this “outside” as an alternative based in tension between fiction and nonfiction. Begun in 1973, The Mythic Being series was, in her words, a transformation of individual self into its seeming opposite: “a Third-world, working class, and overtly hostile male.”5 The Mythic Being materialized in several forms: in the public spaces of New York City he inhabited, in Village Voice monthly advertisements, in drawings and posters, and later, while Piper studied philosophy at Harvard, in photo- documented performances and verbal description. The boundaries that this work traversed, the tensions of passing from inside to outside and back, are multiple. It operated outside the mainstream art world but was made by an educated insider; outside and inside the lineage of western phallocentric discourse; outside and inside identification; in and out of gender roles as well as crossing between the roles of self and other. All were activated within the site of the gallery ad pages, pointing to the institutional framework of art.

Most ads in the series consisted of the Mythic Being’s image (a photograph of Piper in her drag persona) and a thought bubble drawn in crayon or collaged over the original photograph, with text handwritten in crayon or pen. The source material contained in the bubbles was alternatively derived from personal journal passages written in Piper’s adolescence, her thoughts as an adult, or the thoughts of her character. The ads were noticeably odd; the ambiguity of gender underscored by the indistinctness of race, the text disassociated from the figure, the content clearly differing from the intent of a typical ad.6

The ads combined a fictional persona and the “real” past of Piper. In order to sustain the persona, Piper/the Mythic Being recited diary passages as mantras. The interaction of biographical and fictional obfuscated the distinction of artist and character. Her project revealed at least three personae that thwarted any attempt at demarcation: Adrian Piper as artist, the youth who wrote the personal journal passages, and the Mythic Being. In essays and notes about the work’s construction and execution, Piper demonstrated a variety of approaches that refused to enable the reader to ascertain any “real” Adrian Piper–in terms of age, class or gender–or any coherent authorial voice.7

The calculated inconsistencies within the signs highlighted their artificiality. Piper set up a series of structural parameters, but her parameters–in which the vocabulary of conceptualism was meant to counteract the individuality of artistic gesture–employed the signs of identity. As early as the 1970s, Piper was articulating an anti-essentialist identity politics in art.8

Piper explained her method as follows:

Criteria for selecting mantras from my journal:

1. They must be short–no longer than a short paragraph.

2. They must contain the term and be about ‘I’–no objective description.

3. They must deal with important events in my life, or important relationships.

4. It would be good if they could all involve women–I don’t know if that’s possible. There haven’t BEEN that many.9

The way passages were specified and utilized, the choice of how and where to insert the persona into society, and the writing surrounding production of the piece confirmed multiple personae rather than a single, unified self. Treating her personal journals as found objects and employing autobiography as a literary device, Piper underscored how the autobiographical and the fictional, the subjective and the constructed are always in flux. “Preparatory Notes for The Mythic Being (1973-1974),”10 conveyed some of Piper’s divergent approaches–from identifying the thoughts of the Mythic Being as identical to her own to including footnotes that describe the Mythic Being as a “public persona” who shared nothing in common with the artist but the English language. The simultaneity of positions tied Piper to her persona, who is completely fabricated and yet makes utterances that do seem personal. Piper alternately identified and dis-identified with the character, who is but isn’t herself. Consider the following Village Voice installments that juxtaposed her confessions about wanting to be thin, her daydreams about boys in class, or her positioning in the art world relative to other conceptualists

10-13-61: Today was Buffie’s party. Now I’m sure I like Robbie much more that Clyde, but I think Robbie likes me and Liz equally. I still like Clyde a little, but not very much, and I’m not sure the feeling is mutual.

3- -66: You’re welcome.

5-30-68: Dr. Kantor has suggested my stopping therapy because I ‘treat therapy too casually’…

6-16-69: I may not be sticking to my diet exactly, but I Know I’m doing well enough that I should be losing weight. And damn it I’m not.

4-12-68: I really wish I had a firmer grip on reality. Sometimes I think I have better ideas than anyone else around, with the exception of Sol Lewitt and possibly Bob Smithson, whose ideas I really respect.11

Chosen deliberately to contain the word “I” and referencing important past events, the utterances of the Mythic Being and his public appearances were bound to foment confusion not only in her audience, but also ultimately in her self. Torn between her persona and the familiarity of her mantras, the autobiographical and the fictional were ultimately conflated. In “Note on my Persona #3, 10/1/73,” she wrote, “I find myself getting very involved in his mental framework. Chanting the mantra suspends me in a tightrope between two person- alities. Perhaps I’m driving myself to schizophrenia.”12 As practice, The Mythic Being afforded Piper a vantage that simultaneously threatened her sense of psychological coherence. Despite having chosen a persona far from her personhood, the distance between the two had collapsed. Although used as a technique to investigate identity’s operation, the power of identification pushed the experiment to its limits. The extended project of The Mythic Being ultimately fragments the agency of the artist as subject at the crux where social and personal overlap, thus isolating identity as a potentially critical perspective.13

Numerous artistic trajectories in the 1980s were influenced by radical strategies developed by Adrian Piper in the 1970s. Examined and re-examined were mechanisms by which the political affects the personal and how both are defined by language and images. I relate the legacy of Adrian Piper to the practice of Felix Gonzalez-Torres because both analyze the function of self in artwork and address the politics of form with a strong commitment to acknowledge ideological and political currents within identity, all the while using identity as a vantage for undertaking a methodological critique. Since the terms of identity were used to address societal crises–racism and homophobia–the stakes of this analysis were very high for both artists.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Art About Love14

In the mid to late 1980s, art came under attack by conservatives in the United States just as the AIDS crisis was becoming increasingly visible. Felix Gonzalez-Torres responded by representing love in ways he believed would disarm the political strategies of homophobic civil leaders. Based in critique of the image and informed by a commitment to the politics of identity, his artwork approached the political by weaving subject matter into the viewer’s physical interaction with the object, thereby implicating the viewer’s identity in the artwork’s operation.

Perceiving love as an authentic emotional experience and yet a constructed social category, Gonzalez-Torres activated it at the juncture of personal and political. His work animated simple objects into poetic scenes about love, alluding also to bereavement for lost loved ones. While the love expressed was deeply personal, its loss was the consequence of neglect by a government indifferent to the AIDS epidemic. In this way, his artwork addressed both the private and the public meaning of love.

When right-wingers such as Senator Jesse Helms, Senator Alfonso D’Amato and Patrick Buchanan exploited contemporary art as an example of what they considered to be declining social morals, the political conditions begged analysis of the forms of representation. Synthesizing the achievements of several significant art movements, Gonzalez-Torres sampled from the aesthetics and vocabulary of Minimalism and Conceptual Art. He took “love” as his works’ subject matter, Minimalism as its formal referent, Conceptual Art as its method, and identity as its politics in order to make a statement.15 Feminist conceptualists were a significant influence on his work. Their refusal to represent the body, developed as a form of resistance to the objectification women, was an imperative mechanism

Minimalism as a formal referent grounded the work in the transition from transcendental viewing to an embodied interaction, and conceptual methods formed the work’s subversive strategies and thus resisted co-option into conservative offensive. Based in the perspective of identity, Gonzalez-Torres’ articulated intention to “re-frame the terms of the argument” resulted in a major contribution to the legacy of Conceptual Art.16

Many of his artworks interacted with the exhibition space and engaged the physical presence of the viewer’s body. But unlike minimalist endeavors, the work did not assume an un-interrogated viewer. Rather, it urged its audience to define a more specific personal position within the social matrix. Gendering and sexualizing the viewing experience, the artwork of Gonzalez-Torres disallowed neutral spectatorship. In effect, it highlighted the “bodied” subject of 1960’s Minimalism, which, according to Rosalind Krauss, had set the stage for questioning the particularities of the body with its respective socio-political implications. Krauss wrote:

“That corporeal condition…which within 60’s Minimalism was still directed at a body-in-general within a rather generalized sense of space-at-large –that condition became ever more particularized in work that has followed in the 70’s and 80’s. The gendered body, the specificity of site in relation to its political and institutional dimensions–these forms of resistance to abstract spectatordom have been, and are now, where one looks for whatever is critical…in contemporary production.”17

Gonzalez-Torres’ “Untitled” (Loverboy) (1990), situated Minimalism’s space/object/body politic in identity. Blank baby-blue paper stacked upright at an ideal 7 1/2 inches, the work was clearly gendered by its title, while the social conventions of gender indoctrination were insinuated by its color. Having assumed the aesthetic of “primary structure,” the subject of love was activated by minimalist vocabulary rather than through depictions of acts of affection or sexuality. Moreover, this activation expanded in that the embodied viewer was encouraged to take away a sheet of paper. Since “Untitled” Loverboy) was sexualized by its secondary title, participating viewers chose to enter into a particularized exchange–accepting an amorous bond along with a souvenir. In intent and purpose, Gonzalez-Torres’ work triggered the viewer’s identity consciousness.

The act of taking away became amplified in his candy-spill pieces, where viewers were invited to pluck up an edible treat. As in the previous example, secondary titles directed meaning, urging viewers to think about what they were consuming. Although the various candy-spills made meaning in entirely different ways– “Untitled” (USA Today) (1990), for example, invoked a negative connotation for the candy spill–many of them took love as their subject matter. “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) (1991), can be read as memorializing Ross Laycock, Gonzalez-Torres’ life partner who passed away from AIDS that year. One hundred and seventy five pounds of candy, representing the body mass of his deceased lover, were poured in the gallery corner like a minimalist artwork (or perhaps like the wilting of Minimalism in the hands of practitioners such as Lynda Benglis or Robert Morris). The candy, called fruit-flashers, portrayed Ross by emulating his body weight, which withered away by the act of audience consumption during the course of its exhibition. By allowing the artist to place a piece of his artwork into their mouths, audience members were directly implicated as they ingested the symbolic equivalent of a lover’s body. This ritualistic gesture engaged the audience in a physical interaction with the love life of the artist, corroding not only the binaries of self and other, but of subject versus object of art, as a piece of the artwork literally melted into its participating audience.

For Gonzalez-Torres, the subject of love followed from the legacy of Feminism’s groundbreaking observation that “the personal is political.” Public attacks on homosexual life had also made manifest the inverse: the political is also personal. In his billboard projects, Gonzalez-Torres tackled the binary opposition of public versus private in terms of form and content.18 “Untitled” (1991), was a work of public art displayed on twenty-four billboards throughout New York City. It depicted a photograph of a bed, unmade and recently occupied by a couple. An image that spoke of intimacy was pictured via the very public medium of the billboard. Further, presented outside the art institution, the work reminded every viewer that “private” is a discursive category. Although deliberately open-ended, the image may have led the viewer to envision one of the imprints as that of his or her own body, evoking the presence or absence of a partner. It also triggered a series of questions about the legal boundaries of the private and public domain. Who gets to have privacy? Who is supported and who is persecuted for his or her love life? What forms of love and coupling are accepted or rejected by the state? Depending on the orientation of the viewer, his or her identification was teased out.

The work resonated with a profound sense of longing, its angle overlooking the bed in a nostalgic glance, the pillows tilted towards one another, still bearing the impressions of the heads of the couple who slept together, and could have been read autobiographically as the artist’s personal memorial to his beloved partner. Loaded with the tensions of these polarities–personal versus political, private versus public–the work revolved in a gravitational field of love.

Kori Newkirk: Testing the Wind

By the 1990s, the amount and significance of image circulation continued to escalate exponentially and infiltrate numerous aspects of daily life. The analysis of the visual as language and the investigation of representation in art that developed over the course of the 1980s in the works of artists such as Gonzalez-Torres became a model practice. Since the 1990s, art has increasingly become an organic site to examine the complex ways in which images make meaning. Subsequently, it has also become a site to isolate, even for a brief moment, the ways in which oppression is manifested through every particle of our language. Kori Newkirk’s oeuvre persistently addresses multiple possibilities to get at meaning as it seeps through seams of the visual and tangible world. He activates resistance through humor, gesture, encoding, and other sly or oblique ways of communicating and planting messages.19 The cord that ties together Newkirk’s incredibly diverse body of work is his activation of the semiotics of materials. Moreover, the episodic and calculated use of his own image serves to analyze ways in which meaning is rendered through race as a visual category.20 Newkirk does not attempt to portray identity, but instead investigates its intricate interactions with the world at large. By using his own image, Newkirk’s practice does not overlook the historical critique of artistic authority. Rather, like other artists working critically with identity, it follows from such critique.

Newkirk addresses the question of authorship in the social system of sliding privileges that is the world in which we live, where the individual is privileged in some senses and underprivileged in others. Accentuating the relativity of privilege, he ties it to a broader philosophical investigation about the relations between artist, object, and viewer, where the question of privilege is also one of methodology. What should be the site of intervention for the political in art and where is the agency that gives it meaning? Is it in the forms or in the images? Is it in the conditions of distribution or in reception? Does the artist or the object provide context? These questions derive from historical debates focused on the site and methods of political art, ongoing since the days of the Frankfurt School.21

Newkirk fragments the idea of “the artist” into various categories by which his figure can be understood, thus bringing identity to bear on the extended project of political art. His goal is neither to deny experience nor to represent it, but rather to understand how it comes to be rendered through language. If Robert Morris’ I Box (1962) is an obvious referent, Newkirk’s elaboration insists on an examination of the “I” and the images of that “I” within a matrix of sexuality, gender and race.

Testing the Wind (2004), functions as a sentence written out of photographs: two horizontal, extreme close-ups of the artist’s face and a vertical shot of his arm pointing towards the sky. The sequence takes viewers through three stages of motion intended to test which way the wind is blowing these days in American culture. His is a slippery commentary meant to signify one thing to those who get it, another to those who think they get it, and yet another to those who don’t get it (in that they should be aware that if they have to ask then they will probably never know). The point, as catty as it may be, is not about who gets it, but that by visualizing a gesture and thus “putting it into words,” Newkirk’s message is captured and codified between body and image. The codified message functions in a mode of sustained release, its meaning retrospective, unraveling at the pace and specificity of each viewer’s constitution.

First lips, then lick, and now lift: Newkirk’s gesture, so economically animated, is both flirty and flippant. The seduction and warm tones of the first two frames, its references dipped in eroticism, turn vertical in the final photograph where a diagonally composed arm moves to point at the cool-toned sky. The horizontal pointing finger, an icon used by artists including Marcel Duchamp and John Baldessari, has swung upwards, its orientation in the frame associative of inflammatory graphics of the political poster. The pointing finger also evokes those symbolic gestures and movements associated with public statements of protest. The work has multiple meanings, depending on the cultural context of the reader. of consequence is not what each code means exactly, but the ways in which meaning is made through intertwining sets of social, cultural and political signifiers

How the subject sees and is seen in the world functions through identity–and identity in western culture is largely formulated through its relationship to images. Testing the Wind investigates the relationship of images to the act of photographing, to the framing and encoding of images, and to the ways in which the photographic image relates to the eroticized, racialized, and gendered subject. But probably more than anything, Testing the Wind is concerned with the insistence on the part of the critical left to reduce complex investigations into identity to autobiographical portraits.22

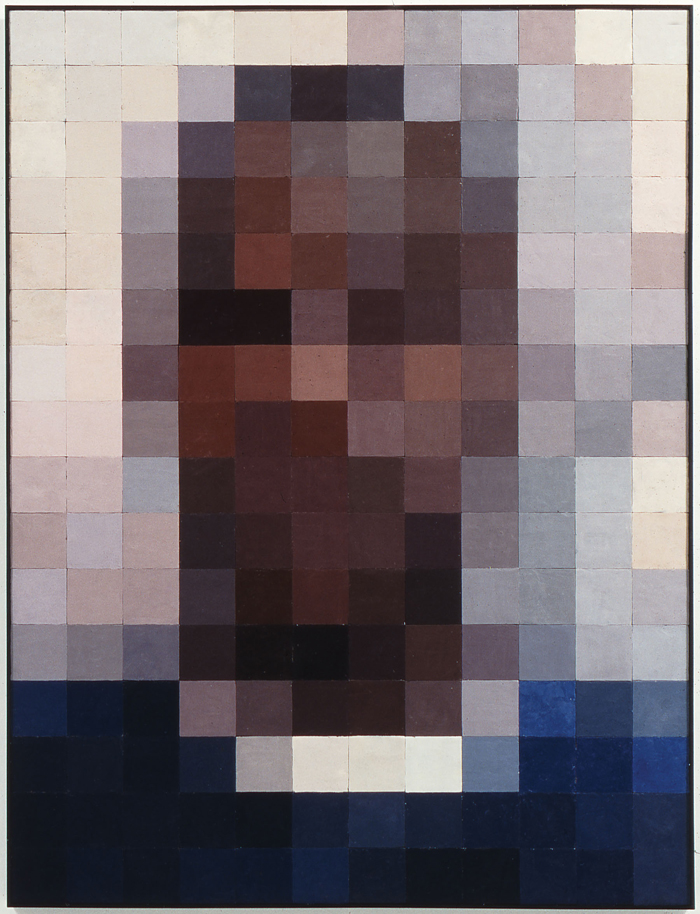

Meaning that never comes to the viewer head-on is the modus operandi of Umbra (2004), a hanging sculpture that spreads across the gallery ceiling. It is in fact a sizable, fully functional kite. Painted on the inside panels of its square lattice wings are color blocks, which, from an oblique perspective reveal a highly abstracted image of the artist’s head, pixilated to the threshold of recognizability. Referencing both experiments of avant-garde graphics and op Art, but also the delib- erately pixilated distortion of facial features aimed to disguise identity on television (as in Newkirk’s Channel 9 and Channel 11, both from 1999) the work inspires a range of interpretations simultaneously. A term used to describe a type of wind, the title Umbra augments the work with manifold possible meanings. According to the oxford English Dictionary “umbra” means: “the shade of a deceased person; a phantom or ghost,…a mere shadow of something,…an uninvited guest accompanying one who is invited,…the shadow cast by the earth or moon as visible in an eclipse.”23 If each meaning initiates a distinct chain of associations, it testifies to how language functions through so many different types of tropes. Take the multiple connotations that could be derived or activated through the analysis and use of the word “shade”; from Sigmund freud to vogue-ing, they are part of living language. Identified by ferdinand de Saussure as a system of differences in circulation–in langue–language still maintains the signification of hierarchies. Newkirk’s artwork is based in critique of the dominant structure that positions identities through classification of social hierarchies, rather than social and cultural differences.

Positioning is activated both physically and philosophically by Umbra. Newkirk’s phenomenological approach to the function of vision affects the actual location of the viewer in the space of the gallery and in relation to the image. To perceive the color blocks as image, the viewer must reposition herself to look at them from a skewed angle. This movement and its meaning has a historical referent in Hans Holbein’s painting The Ambassadors (1533). In order to see a skull, painted in perspectival anamorphosis across the foreground, one must look at the painting from a very particular vantage point. when viewed conventionally, the envoys seem only to flank their instruments of art and knowledge. “Masters of the universe,” the truth of the subjects’ mortality is revealed only from an oblique angle.

In “Anamorphosis” from Seminar XI, Jacques Lacan argues that the frontal point of view in Holbein’s painting derives its meaning from the oblique angle. Lacan uses anamorphosis to demonstrate that it is in the perspective of the unconscious that we situate consciousness.24 This visual device puts into operation what resides between desire and the Lacanian “real.” The anamorphic image is rendered in The Ambassadors to facilitate meaning for the symmetrical perspective–death, represented by a skull, gives meaning to life. For Lacan, concerned with broader questions of the subject and the gaze, anamorphosis “complements what geometrical researches into perspective allow to escape from vision.”25 In Newkirk’s work, it is the image of the artist that gives meaning to the kite through vision, oblique vision. Perceived askance, his portrait emerges from a minimal palette of color swatches, its elusory presence illuminating that which escapes every viewer’s consciousness. In the spirit of Minimalism (as queered by Gonzalez-Torres), Newkirk activates the viewer’s body toward multiple-angled viewing, there to reveal what the head-on view cannot.

The use of perspective in art has historically made visible the humanist philosophy of being. Throughout the 20th century, much has been written about humanism’s reliance upon social hierarchies maintained through violence, both overt and covert.26 The ways in which vision and language render subjectivity have been at the heart of poststructuralist critique of humanism, Lacan’s arguments not withstanding. Newkirk’s artworks spring from these critical perspectives–as he insists upon questioning the ways in which the specificity of identity must enter into the analysis of meaning.

Conclusion

Critical artistic developments in the last forty years have brought the politicization of identity to bear on discussions about critical art. That the recent Whitney Biennial 2008 clearly revisits the identity politics of the Whitney Biennial 1993 provides further impetus to reconsider the enormous contributions of identity politics to recent art history and to define the multiple interventions it has performed. My brief outline taps into a mere segment of a much larger group of artists who have been working with critical identity politics since the 1970s, increasingly so since the 1980s, and continuing into the present. These artists share a careful integration of the achievements of contemporaneous critical art with a focus on an analysis of identity construction, highlighting the necessity to consider identity not as an element that fragments the left, but as a contributing and necessary perspective.

Given recent reconsiderations of Feminist artistic strategies (and, moreover, despite widespread resistance to accept identity politics as potentially critical), it has become increasingly clear that identity is the lens by which issues such as the relation of subjectivity to artistic authorship, the function of images and objects, as well as the location of the political in artistic communication and exchange can be investigated. This is not to suggest that identity is purely thought and not experienced. Rather, it is precisely this tension between experience and its manifestations that inspires the examination of critical identity politics. Finally, as we are well into a digital age with its staggering proliferation of images, the analysis of visual language as it relates to identity is a foundational concern, no longer a supplementary one.

A scholar and curator of contemporary art, Dr. Nizan Shaked is Assistant Professor of Museum, Curatorial Studies and Art History at California State University Long Beach.