The original is unfaithful to the translation.

—Jorge Luis Borges

When Borges characterizes the translation as autonomous, as having its own space and logic relative to the original, he presciently outlines a compelling approach to the internet and our digital age. Indeed, in his short story “Book of Sand” (1975) the author proposes that when confronted with an infinite index, as with the eponymous book, one should return to the medium itself for orientation.

The collaborative duo JODI has engaged the architecture of its medium—the World Wide Web and so-called “net art”1—for more than twenty-five years. In their recent exhibition, Show #31: JODI, at And/Or Gallery in Pasadena, they frame mediated space as something hovering between “the physicality of Cartesian IRL and the invisibility of URL Dataspace.”2 IRL is, of course, shorthand for in real life, and URL is Uniform Resource Locator, the ubiquitous, if illunderstood, naming protocol of online hosting, i.e., the WWW address. This question of a subject’s digital orientation, of discerning where the internet is located and what it’s made of, is central to the exhibition. In the gallery, JODI has arranged a site-specific group of works that commingle the experience of the real with the virtual, incorporating a large sculptural installation alongside a host of familiar technologies, ranging from 3D scanners to Wi-Fi routers. In so doing, they continue their ongoing exploration of computer technology as not only a set of parameters but also a way of translating the world, underlying the fundamental nature of digital space as a hybrid architecture, or what media theorist Alexander R. Galloway has characterized as their interest in “infrastructural modernism.”3

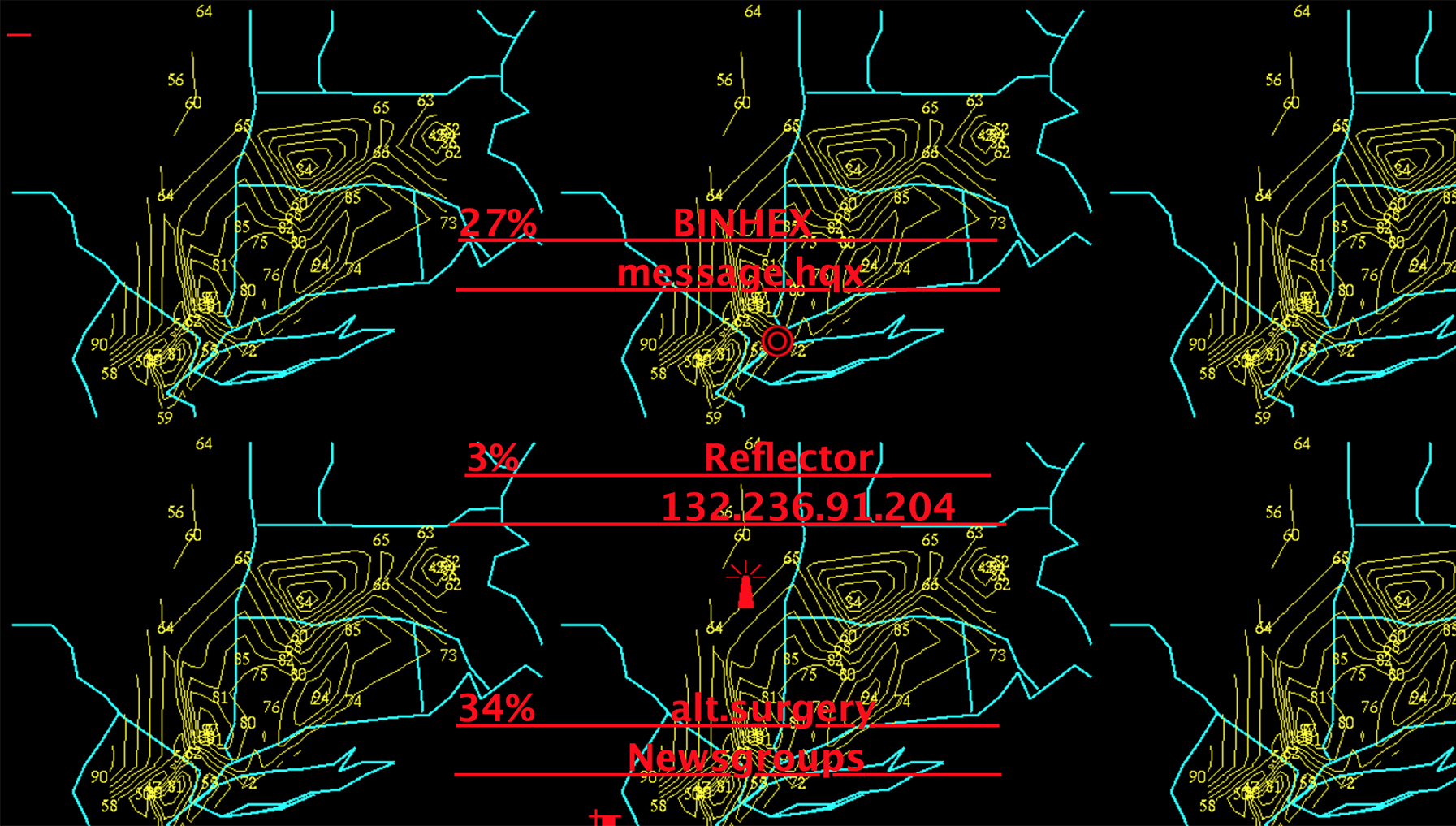

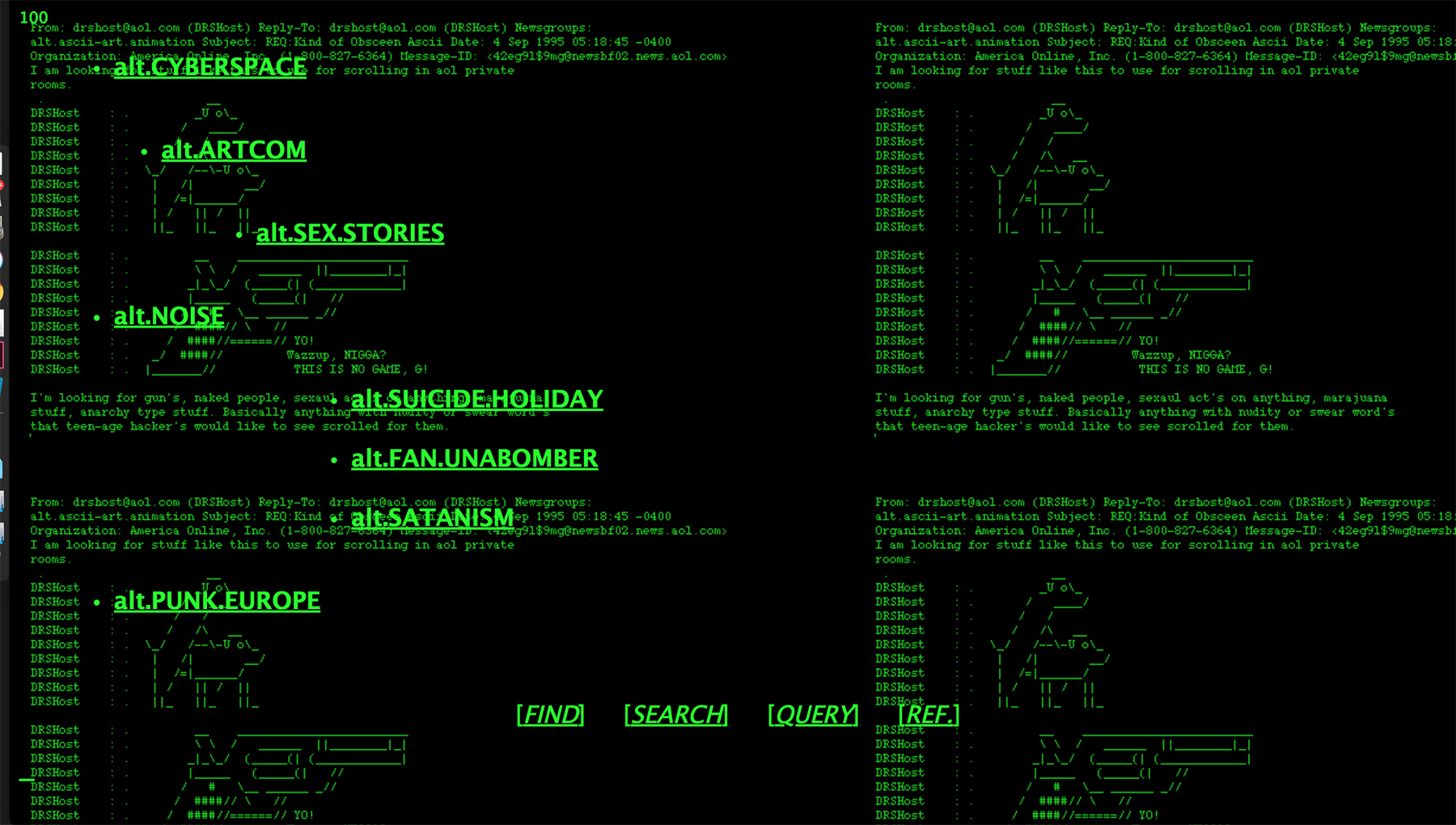

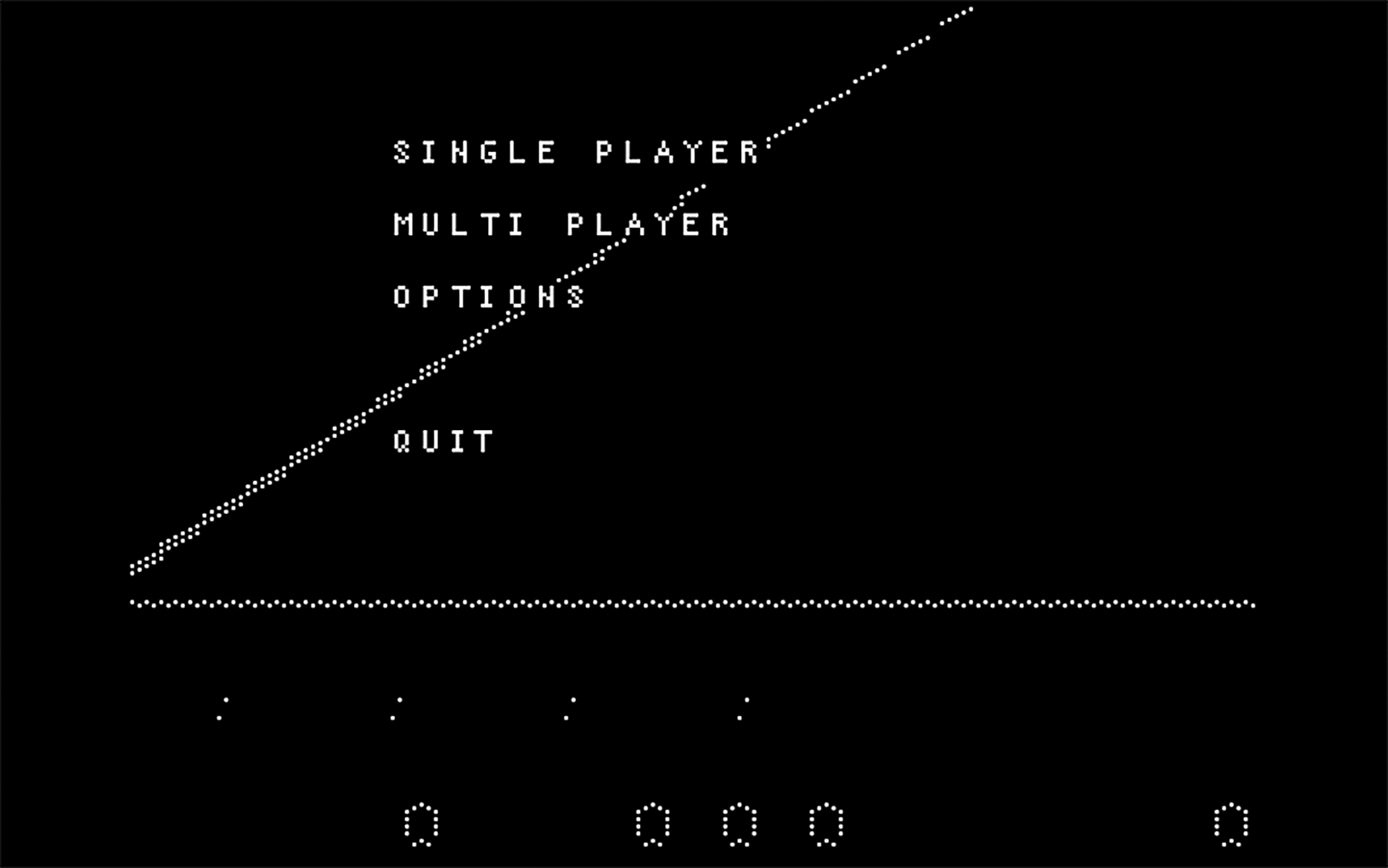

Screenshot from Jodi.org. Courtesy of the artists and And/Or Gallery.

JODI is the hybridized moniker of the Dutch- Belgian duo Joan Heemskerk and Dirk Paesmans, who have been making artwork together since attending the electronic arts laboratory CADRE (Computers in Art, Design, Research, and Education) at San Jose State University in 1995. They are widely regarded as some of the first artists to seriously engage the internet as both a medium and a site—prefiguring the way the web has come to be defined as a synthesis of authorship and network. They began by creating a series of websites that exploit one of the net’s defining features—its reliance on hyperlinks— to assemble protean collections of found imagery and undecipherable fragments of code. Resembling a kind of HTML gesamtkunstwerk, their earliest and best known website (http://wwwwwwwww.jodi.org, 1995–ongoing) remains an evolving personal index of whatever interests the artists, which, seemingly, is everything. Jodi.org remains a compelling project, despite the frustration of not knowing how to navigate the site, precisely for this refusal to establish an ideological hierarchy of its contents. Instead, in what seems to illustrate JODI’s foundational principle, the endless blind-clicking becomes both a means and an end, illustrating the logic of the code as a method of assemblage and the underlying structure of the transfer protocol, or TCP/ IP.4 In this emphasis on the semantics of the medium, its nascent spatializing of information as packets, and the user interface as a series of data thresholds, JODI has created an ontological model that helps to define some of the basic parameters of our information age. In isolating and amplifying this underlying architecture of connectivity, in addition to employing a raucous in-your-face aesthetic, JODI successfully uses the internet to deconstruct contemporary identity in ways that are vitally important, linking our current technologies and rhetoric of progress with essential metaphysical precedents that deserve to be acknowledged and explored.

Indeed, while these more arcane origins of the internet might not be immediately apparent, I would like to argue that JODI’s focus on the digital as a medium and the online environment as a space highlights core concepts that link the World Wide Web with themes found in early Greek philosophy. This link is most articulated in fundamental material questions of the cosmos and how consciousness appears in and orients space via systematic relationships. Specifically, I am interested in JODI’s uncanny ability to engage the digital as both an ontological and mediated threshold, a formal delineation that establishes the urge to map as fundamental to the establishment of the self. This dovetails with what Indra Kagis McEwen argues—in her book Socrates’ Ancestors: An Essay on Architectural Beginnings—is the genesis of philosophy, in which “‘the architectural event’ and the ‘theoretical event’ can be understood as related movements in a single occurrence.”5 This confluence is one that McEwen sees as grounded in early attempts to conceptualize the perimeter of the cosmos and the way craft, or techne (the root of our word technology), informed this process by recognizing and replicating the patterns found in nature. Patterns, according to McEwen, illustrate how things fit together, thereby becoming a template that allowed the earliest philosophers to invent both physical and abstract systems. Indeed, our word cosmos (kosmos) comes from the Greek kosmeo, meaning to arrange and order.6

Often marginalized in traditional art circles, web art, or what is now sometimes referred to as postinternet art (i.e., art that is made in an internet-aware milieu), has been misunderstood, both because of the medium’s inherent immateriality and due to its technical complexity.7 JODI has avoided this trap by engaging the underlying operating systems that give form to data, in a bid to highlight the human desires that weave the net itself. In this way, the group successfully engages deeper phenomenological issues about how perception shapes consciousness and how this mirrors online activity and the exponential growth of digital media more broadly. One of the ways the artists do this, if obliquely, is by framing the internet as a kind of labyrinth, tying our most contemporary analogy (the web) with one of our most ancient (the maze). And it is precisely this correlation to the labyrinth and more fundamentally to weaving and metamorphosis that led me to McEwen’s essay, wherein she reminds us that Daedalus was not only the mythical first architect but also the designer of the famous maze. It is worth remembering that not only was the labyrinth a space created for King Minos in order to contain the Minotaur but that Daedalus was also tasked with designing the subterfuge that allowed Queen Pasiphae to have sexual intercourse with the bull in the first place.8 In this way, the labyrinth, and techne more broadly, can be seen as allegorizing the unintended consequences of network technology today. And it is here, within this spatial arrangement, which is, of course, a prison, that JODI locates one of its central conceptual themes: the way technology both liberates and constrains its users by utilizing systems that are the same as those underlying human cognition. And in much the same way that the observation of patterns in nature becomes the basis for techne, philosophy charts the patterns found in consciousness in a bid to control chaos and conceptualize a universe that can be navigated.9

Screenshot from Jodi.org. Courtesy of the artists and And/Or Gallery.

Screenshot from Jodi.org. Courtesy of the artists and And/Or Gallery.

At And/Or Gallery, JODI foregrounds this focus on mediation and systematic thinking by engaging directly the question of how architectural space is perceived vis-à-vis the body and how the body in effect arranges space in order to establish this system for mapping. What is paramount in this analysis is that there is a dialectic based on entrapment/freedom that is fundamental to not only post-internet art but also the shared origins of technology and philosophy. Theorist Svetlana Boym, who also explores the “synchronicity of the mythic and the logical” in her book Another Freedom, highlights this connection when she observes, “Technology and freedom are frequently in a double bind and often in contradiction to one another.”10 JODI expertly engages this bind from the minute the viewer walks into the gallery by engaging the phenomenon of data both physically and metaphysically.

Entering the gallery one is confronted with a series of modestly sized rooms, arranged clockwise in a tight layout that seems to highlight the viewing experience as architectonic and that ends unceremoniously in a very small room in the back. To exit, viewers must retrace their steps, and JODI exploits this fixed floor plan to highlight how the site and the passage between the discrete works is the basic system through which we experience the exhibition. In other words, JODI choreographs the links between the works through the viewers’ ambulation in order to chart their location in space and establish their position, much like the artists have done through their aggressive use of hyperlinks online. This motion capture, if you will, foregrounds a central tenet of philosophy, as based on the Greek verb gnosco (familiar to us in the word gnosis) as related to a standing figure or gnomon. And it is this emphasis on locating the gnomon, which is also the word for a sun clock and later a carpenter’s square, that makes plain the importance of measuring time and space in early systematic thought.11

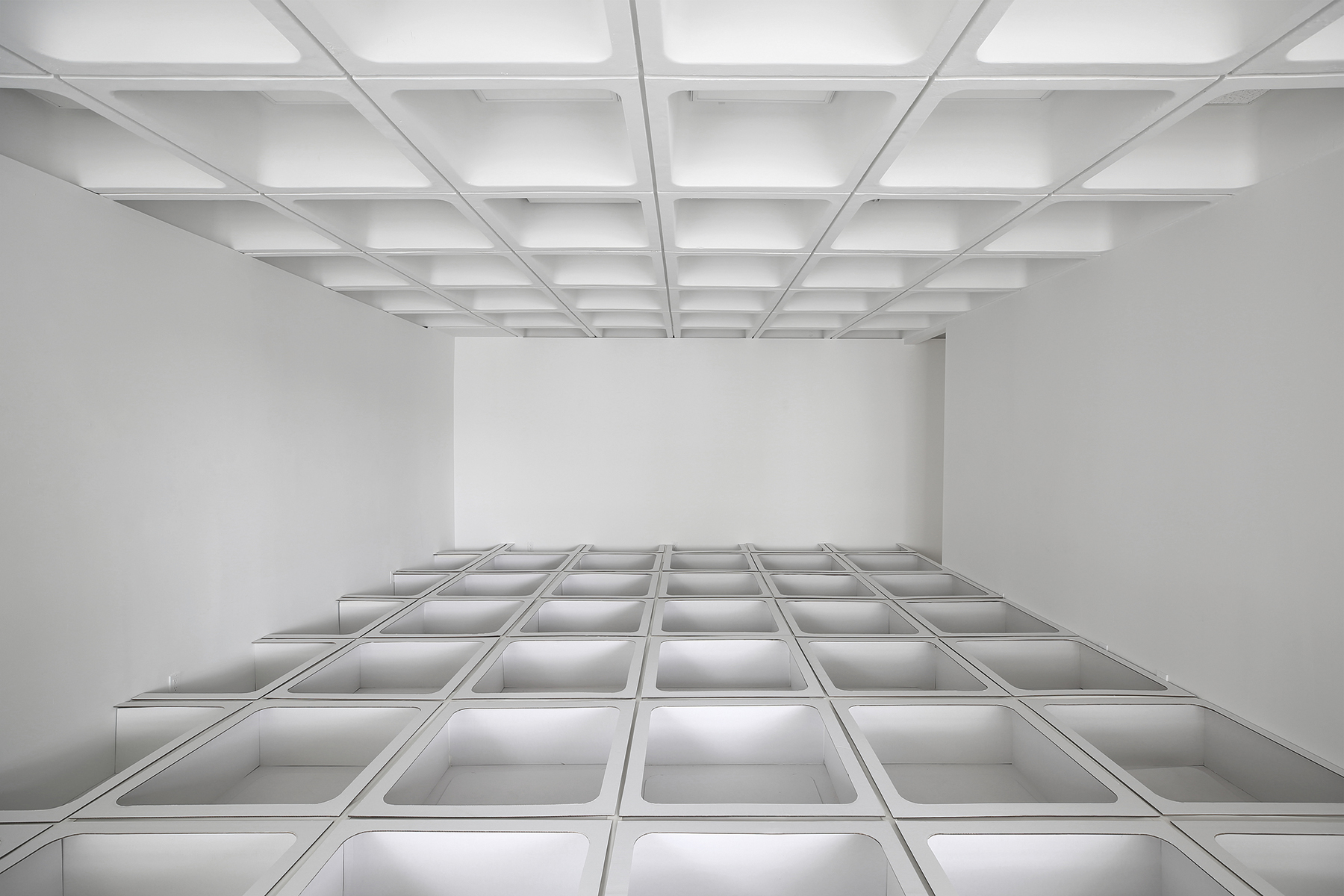

JODI, And/Or Grid, 2018. Site-specific installation. Corrugated cardboard and tape, dimensions variable. Installation view, Show #31: JODI, And/Or Gallery, Los Angeles, May–September 2018. Courtesy of the artists and And/Or Gallery.

Located on the edge of Pasadena, the mid-century commercial building that houses And/Or Gallery has a coffered, cast-concrete ceiling that resembles many Brutalist-era designs that aestheticize the grid.12 In a full-room installation titled And/Or Grid (2018), the artists have cleverly engaged the specifics of the site and its explicit reference to Cartesian space IRL by literally copying the ceiling and recreating it to scale on the gallery’s floor. What began as a Photoshop joke (according to the gallery’s press release) becomes a convincing mirrored environment in which the titular design has been recreated using white cardboard. Resembling a life-sized architectural model and nascent maze, the altered space requires the viewer to literally step from coffered cell to coffered cell when traversing the room, forcing a kind of crab walk or x–y shuffle. In addition, the mirrored perspective tilts the room visually, recalling the familiar trope of digital space as being infinite and self-replicating. By evoking this analog simulacrum, JODI is able to transform an otherwise modestly-sized gallery into a passable virtual environment. In short, they merge the “Cartesian IRL with a URL Dataspace.”

JODI, \/\/iFi, 2017. Raspberry Pi and long-range Wi-Fi adapter, custom software, dimensions variable. Installation view, Show #31: JODI, And/Or Gallery, Los Angeles, May–September 2018. Courtesy of the artists and And/Or Gallery.

This uncanny shift from being literally outside the gallery to being metaphorically inside the matrix is preceded by a small anteroom that houses \/\/iFi (2017), a simple antenna arrangement perched on a tripod, which announces that the environment is a Wi-Fi hotspot. Next to the router, which is not linked to the internet, is a wall-mounted monitor that lists the network and shows location tags assigned to gallery goers in real time via their cellphone’s MAC address as they walk through the installation.13 Thus, the Wi-Fi zone and tracking analogy set the stage for the exhibition, establishing it as a space that is both literally and metaphorically linked, akin to a woven net or an ordered cosmos. This ontological shift seems to suggest that the artists intend to fold the viewers into the work itself and that when entering the installation in the next room—and by extension a virtual reality—one’s body is also being translated into an avatar. In so doing, JODI highlights another important rubric of the exhibition—the scan—in what might be said is the medium of the mediation.

JODI, \/\/iFi (detail), 2017. Screenshot. Raspberry Pi and long-range Wi-Fi adapter, custom software, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artists and And/Or Gallery.

This transition establishes the conceptual basis for the entire exhibition, an ontological threshold whereby the body is translated into a data point or signal as it enters and moves through the gallery. In other words, by articulating the intersection of consciousness and containment—via technology—the human participant manifests the epistemological event of self-awareness. This process is highlighted when visitors must literally step up, over, and into the cardboard cells in order to enter the installation. The threshold is, of course, highly symbolic and used historically to designate a break with the everyday, most notably in ritual spaces designed to differentiate between the sacred and the profane.14 In drawing attention to this haptic transition, JODI introduces two related motifs that are essential for exploring all four works in the show and suggest a compelling overlay of digital and analog thinking; motifs that I will refer to as the means and the end, but that could just as easily be considered a warp and weft. The first theme is the intersection of architecture and ontology and the second is the way post-internet art echoes weaving as a prototypical metaphysics that arises out of a techne of “well crafted parts.”

THE MEANS

When Heemskerk and Paesmans first burst onto the scene as JODI, they were a couple of well-trained provocateurs who had both art and computer science backgrounds, and who were working in tech in the 1990s at just the right time to witness how it worked and catch a whiff of its impending corporate takeover.15 As such, they understood the internet as a system that could and should be disrupted or, more simply, fucked with, utilizing punk, Fluxus, and Dada strategies of collage and juxtaposition to confront and co-opt the mechanisms of power.

This critical view of capitalism’s takeover of the internet is perhaps best illustrated in their infamous acceptance speech for a 1999 Webby Award for internet art: “Ugly commercial sons of bitches.”16 This prescient observation, which adhered to the Webby’s strictly imposed five-word maximum, seems to capture what at the time was the impending transformation of the internet from a predominantly peer-to-peer domain into what today is clearly a monstrous hybrid of capitalism and big data. Furthermore, it presages JODI’s evolving practice which at the time was increasingly focused on modifying video games. This work, more than the familiar non sequitur hyperlink collages that populate their websites, suggests some of the deeper epistemological themes that have come to define postinternet art, as popularized by later artists such as Cory Arcangel, Camille Henrot, and Hito Steyerl.

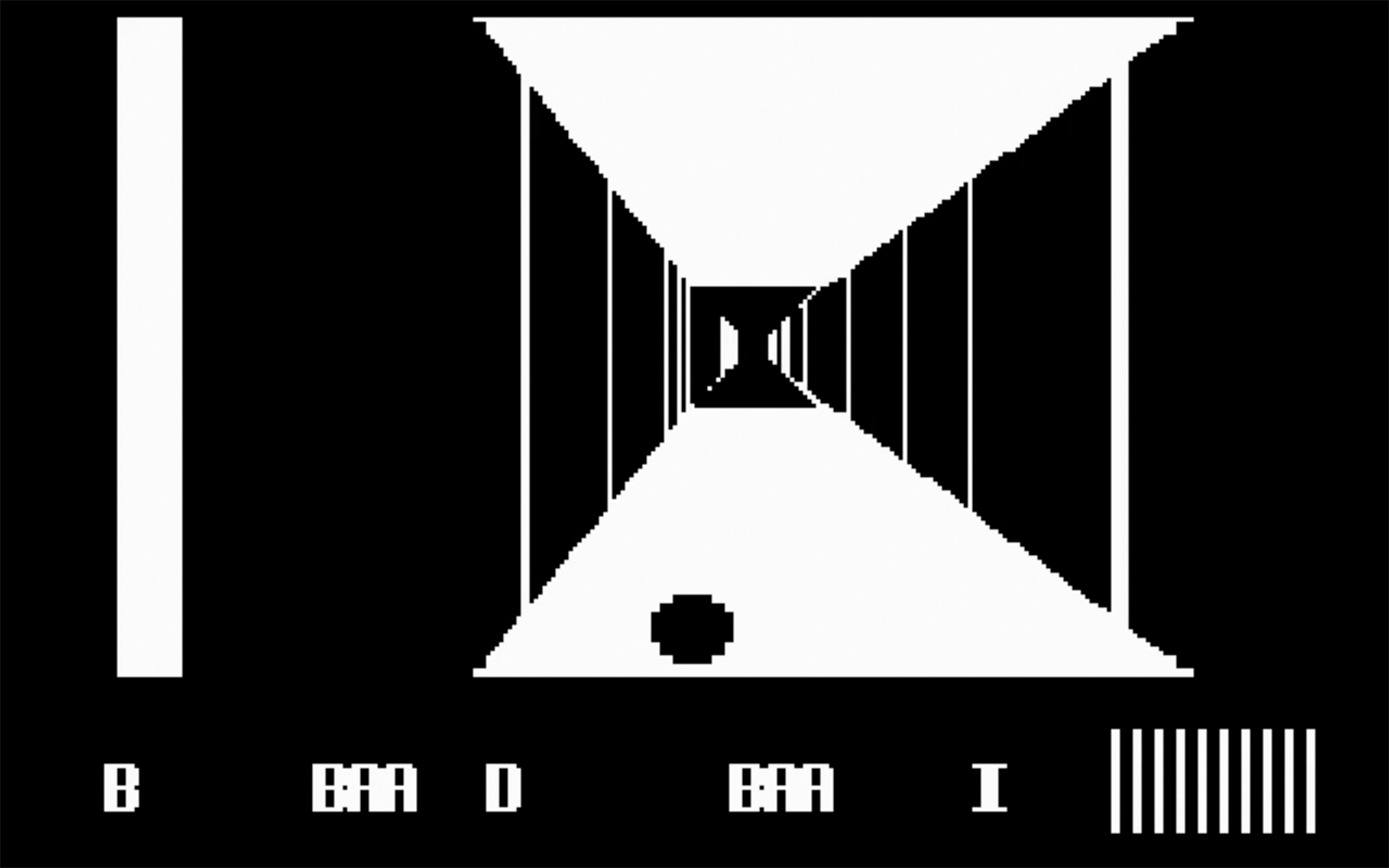

Indeed, in JODI’s first modification, or “mod,” for which they were awarded the Webby, the duo used the popular Nazi first-person shooter game, Wolfenstein 3D, to deeply probe the experience of a totalized virtual space. In this work, titled SOD (1999), JODI drew a visceral correlation between the psychology of the user, the interior of the castle, and the internet’s architecture of surveillance. Altering the source code of Wolfenstein 3D, they hacked the Nazi headquarters into an endless maze of starkly minimalist black-andwhite corridors and rooms. What is so successful about SOD and later games modified by JODI, including Untitled Game (1997–2001), based on Quake 1, and Max Payne Cheats Only (2004), is the way they convincingly invert the architectonic experience of the digital environment, transforming the sequential rooms into an experience that is at once more specific and less.17 In other words, they foreground the logic and ubiquity of the code to establish the primacy of virtual space and then systematically deconstruct it—a disassembly that reveals the relationship of the users to their environment and seems to evoke both the interconnectivity and the chaos of a so-called hyperobject.18 In this way, they highlight the medium specificity of the digital in a way that feels profoundly existential, evoking the relationship of myth to assembly as consisting of countless transistors and bits of information. This emphasis on hacking and the pixel as the basic constituent element of the castle mirrors the design of the labyrinth as being daidalon (the root of Daedalus’s name), a term that denotes “a cutting up or cutting out…associated with the complimentary notion of adjustment, or fitting together.”19 In SOD, the player moves through infinite rooms consisting of cut up and arranged planes, where all the surfaces are stripped of detail. Instead of the promise of escape, all that is left is a corrupted pixelated homogeneity and endless passage across infinite thresholds. In designing an environment that is premised on timelessness as much as imprisonment, JODI poignantly crafts a phenomenological game that flips the script, illustrating the connection between the psychology of the user IRL and the Cartesian laws of a virtual URL space. In this way, they design what inevitably resembles the “inextricable net” of the original mythic labyrinth.20

JODI, SOD (detail), 1999. Screenshot. Modified video game, played by user and uploaded onto YouTube. Courtesy of the artists and And/Or Gallery.

The digital spaces of Wolfenstein 3D and other similar first-person games set the stage for this overlap between the bureaucratic efficiency of fascism and the totalizing tautology of the internet. At this inflection point, JODI successfully deploys what Galloway contends is the suspension “of the distinction between art and technology…,” where “the beauty of code comes not from function and elegance but from a different set of virtues—dysfunction and inelegance to be sure, but also confusion and excitement, violence and energy.”21 This inchoate environment would seem to suggest something resembling a ritual space or, at the very least, a theatrical staging, thereby folding JODI back into a philosophical conversation about cosmic origins and what Boym argues is the knotted origin of techne and mania, where “freedom was not always a ‘gift of the gods’ but more often a theft from the gods.” And “Promethean techne leads to deliberation while Dionysian manias lead to deliverance.”22

JODI, UNTITLED GAME (detail), 1997–2001. Screenshot. Modified video game, played by user and uploaded onto YouTube. Courtesy of the artists and And/Or Gallery.

According to McEwen, this combustible intersection, wherein art and technology seem to metamorphose beyond the glitch into something entirely new,23 can be seen as pointing to the birthplace of philosophy, where the “theoretical event, so called, of sixth-century Greece hinged upon an emergent awareness of order whose genesis, whose coming to-be, was rooted in early Greek perception of craft as the revelation of kosmos.”24 For McEwen, as we have seen, one way to approach the advent of this speculative moment is to explore its relationship to architecture and, by extension, to technology, and she argues that both are founded on the desire to navigate chaos, what the Greeks referred to as aporia or boundless nature.25 Early Greek metaphysical thought is rooted in this tension between abstraction and the need to fit things together. The balancing of these antagonistic forces by emphasizing their innate, albeit shifting, bonds of connectivity can be seen in pattern making, for example in dance, weaving, and shipbuilding, as well as the aforementioned labyrinth. McEwen thus posits that techne laid the groundwork for not only reasoned argument but also the eventual founding of cities, which are laid out to resemble the warp and weft of the loom, as well as the hierarchical systems that are today’s digital databases.

This argument is compelling not only in so far as it evokes the origins of modern computing in the invention of the Jacquard loom, which used punch cards to automatically control the weaving of patterns in cloth, but also in how this manifestation of order through pattern was, according to McEwen, designed to “make the world appear.” She writes, “The word for weaving or plying the loom was hyphainein, which literally means to bring to light, or make visible, and the word for surface…is epiphaneia.”26 In this telling, the process of understanding the world involves bringing to the surface the underlying medium of the apparatus itself, a procedure that sounds an awful lot like the principles of net art.

JODI, Max Payne Cheats Only(detail), 2004. Screenshot. Modified video game, played by user and uploaded onto http://maxpaynecheatsonly.jodi.org. Courtesy of the artists and And/Or Gallery.

JODI’s game modifications seem to rely on a similar logic of measuring the medium, where the specifications of the software are brought to the fore, undone, and reconstituted as a means of highlighting the underlying desire at work in the game itself. In the myth of the Minotaur, the metaphor of the textile is literally a systemized means of constructing and deconstructing space as kosmos, as Theseus uses Ariadne’s ball of thread to guide him out of the labyrinth, after slaying the hybrid bull/ man within. According to McEwen, the connection between weaving and architecture can be seen in “the measure of Ariadne’s dance and the confused regularity of the moving maze traced by the passage of well-taught feet which spins the thread that leads out of the labyrinth and goes on to weave another.”27 In this evocative passage, we are reminded that there is no escape from chaos, just a temporary reprieve via the cunningly crafted dance steps and epiphaneia (perhaps analogous to Boym’s “deliverance”?), which rests on the intersection of techne and mania, much like the internet does today.

THE END

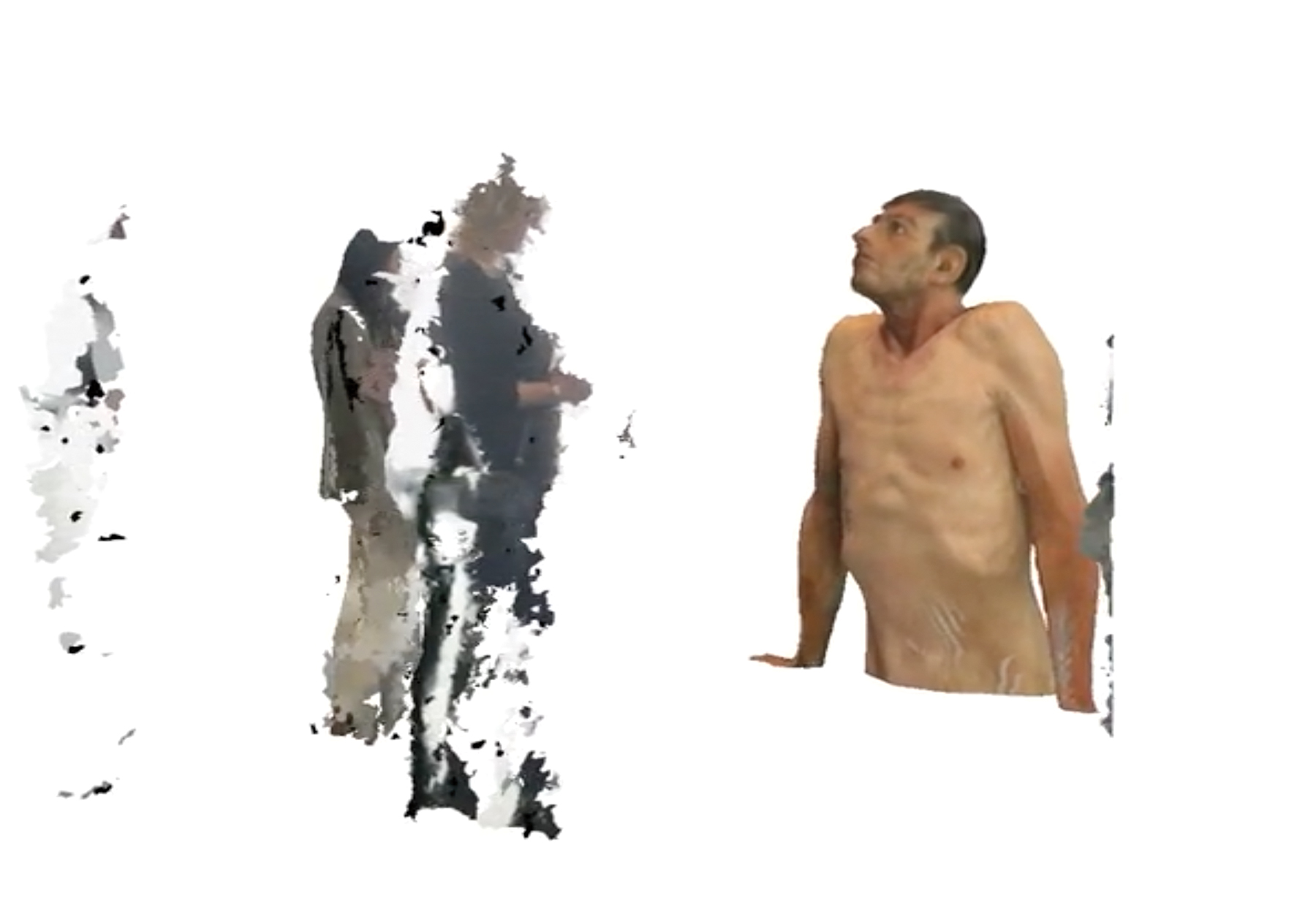

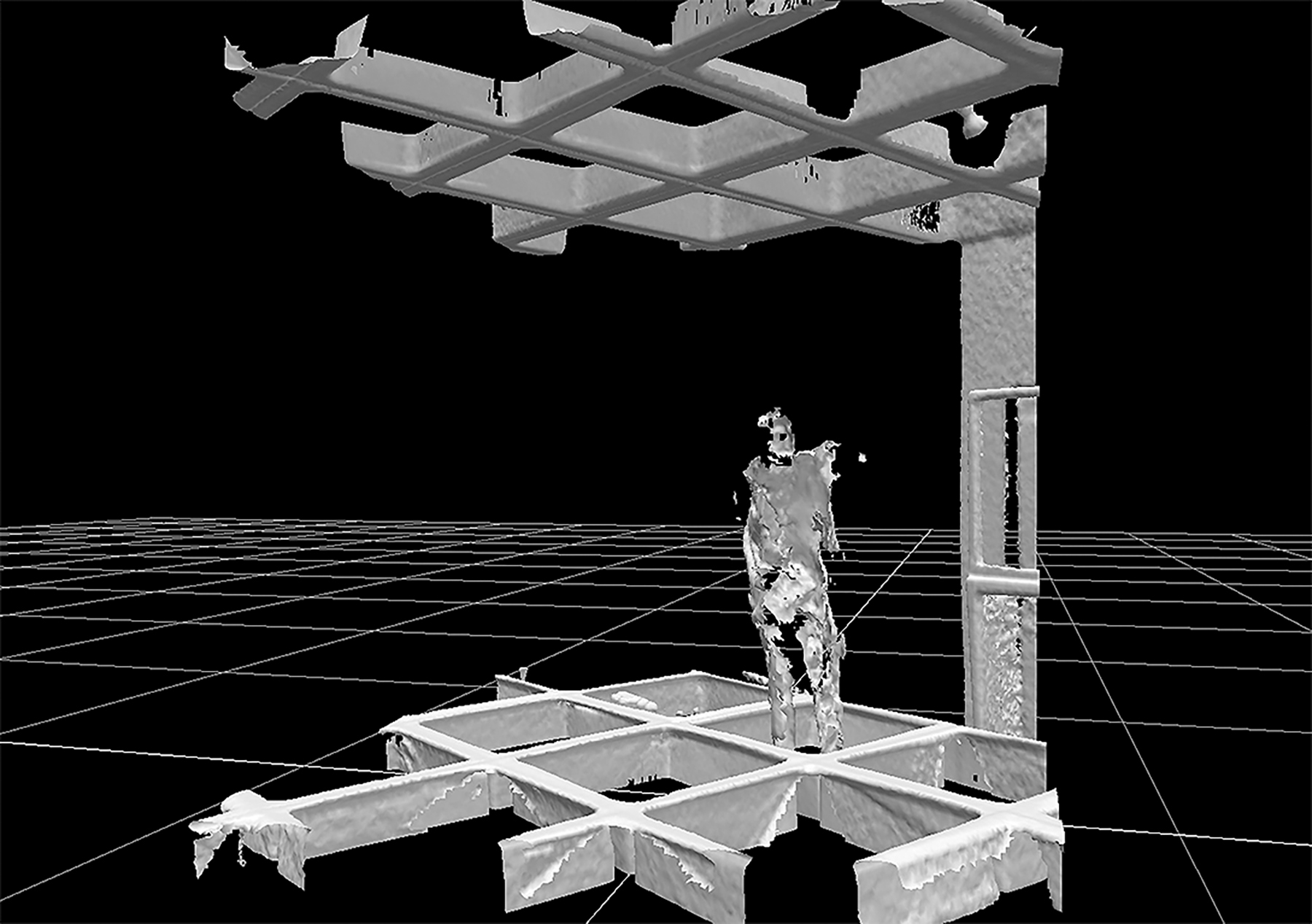

JODI’s more recent work uses 3D scanning technology to foreground the human body in space. Their two pieces And/Or Grid 3D Scans (2018) and Scan Journal (213D.org) #artgallery 3D scans (2018), shown in the rear of the And/Or Gallery, feel like a natural progression from the dystopic environments of the game mods to something more explicitly mythological—where the question of a metamorphic subject is established vis-à-vis the digital threshold. Having already established that the viewer is being tracked in the gallery space through Wi-Fi, both works present images, hosted online, of actual gallery goers who were recorded using a LIDAR (light detecting and ranging) scanner. Following the basic mechanics of radar, this 3D scanning technology uses lasers to capture the surface contours of an object’s x, y, and z coordinates, in what is known as a “point cloud.”28 In this way, the light scan records the body as parts, and JODI intentionally makes quick and superficial scans using a handheld scanning device in order to render fragmented subjects and highlight the medium of the scan itself. The results collapse IRL and URL and clearly resemble the artists’ earlier interest in broken links and butchered code. This unraveling of the appearance of the person in space evokes the processes of cutting and arranging as seen in daidalon and kosmeo.

JODI, Scan Journal (213D.org) #artgallery 3D scans (detail), 2018. 3D scans on custom website, computer, projector, mouse. Courtesy of the artists and And/Or Gallery.

JODI, Scan Journal (213D.org) #artgallery 3D scans (detail), 2018. 3D scans on custom website, computer, projector, mouse. Courtesy of the artists and And/Or Gallery.

The visceral corporeality of these scanned objects as constructed bodies presents us with a hybrid aesthetic that links the modified gallery space to the Minotaur in what might be called, in a nod to Galloway, an infrastructural ontology—an awareness that relies explicitly on viewers recognizing themselves in the mutated figures. This act of self-recognition in an explicitly incomplete and hybrid medium points to how the patterning of a thing—its fitting together—underlies its identity. McEwen writes, “The weaving of the cloth is an unveiling insofar as the person veiled (Earth or the bride) only appears, properly speaking, after she has been clothed.”29 JODI invests the otherwise chaotic form of the scan with the consciousness of the subject by pointing to these frayed edges and rent volumes, thereby setting up an ethical dilemma that is more articulated than in any of their previous works and seems to resonate with today’s fraught online landscape, with its proliferating population of hybrid monsters, trolls, sock puppets, and bots.

Stepping away from And/Or Grid, one enters a short corridor, where the first work is shown on a single monitor. Scan Journal (213D.org) #artgallery 3D scans is a web-hosted piece in which the artists have uploaded a series of 3D scans of people looking at art in different art galleries. Hovering in arrested states and including segments of whatever object they’re looking at, the scans show incomplete digital renderings of people in a perpetual limbo. Despite being intractably frozen, however, they can be viewed from multiple angles, since they are 3D digital files. In their frozen mutability, the bodies toggle between appearing like studies or sculptures in progress and victims of a grisly bombing—their hollowed carapaces and corrupted contours illustrating a grotesque blast pattern. It is hard to avoid this diabolic interpretation. They are incomplete, recognizable as figures but fragmented. Like empty skins, they evoke a familiar sciencefiction trope of clones, both in the sense that they appear in utero, surrounded by black screen space, and because their incompleteness conveys a still-gestating morphology. What is interesting is how familiar these bodies are, resembling avatars in the films Blade Runner 2049 (2017), Annihilation (2018), and Under the Skin (2013). But simultaneously, they appear different and more evocative, especially when compared with the ubiquitous low-resolution images and clunky GIFS that populate the internet today. It is as if an interrupted 3D scan is somehow more alive, precisely because of its incompleteness, a potential for evolution embedded in its ill-fitting parts. This twenty-first-century daidalon has echoes, of course, in the comparatively more recent Promethean story of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) and, as such, the scan seems the logical inheritor of our science fictions.

Hito Steyerl takes up the awkward intimacy that these types of body scans elicit and the political ramifications of those feelings in her essay “Ripping Reality: Blind Spots and Wrecked Data in 3D.” She writes, “3D scanning thus does highlight the idea of the surface by blending in matter, actions and forces. The surface is no longer a stage or backdrop on which subjects and objects are positioned. Rather, it folds in subjects, objects, and vectors of motion, affect and action, thus removing the artificial epistemological separation between.”30 In other words, the 3D scan is like the woven cloth from which it draws its inspiration. To use McEwen’s analogy, the scan allows for the appearance of the thing itself as both “a skin or surface and an appearing (epiphaneia).” And in this manifestation of techne, in the mediated form itself, there is the spark of consciousness, where, “the cunningly crafted thing was able to reveal an unseen divine presence.”31

By emphasizing the incomplete scan (or “wrecked data”), Steyerl contends that we as viewers are given agency to fill in the remainder, a compelling parallel to the Minotaur as a hybrid off-spring and allegory of desire and the way JODI uses architecture to force us to confront our own incomplete physicality as being in perpetual evolution. In this way, the labyrinth suggests one of its hypothesized etymological roots—labrys—or double-sided axe, a word that is also connected to another threshold, the labia. So what of the epistemological separation between us and the data, as outlined by Steyerl? Is it an infrastructural ontology, wherein the technology engenders a new kind of human being? Or does it portend something more existential, where beyond the projected self lies nothing but decay?

JODI, And/Or Grid 3D Scans (detail), 2018. Screenshot. 3D scans on custom website, computer, projector, mouse. Courtesy of the artists and And/Or Gallery.

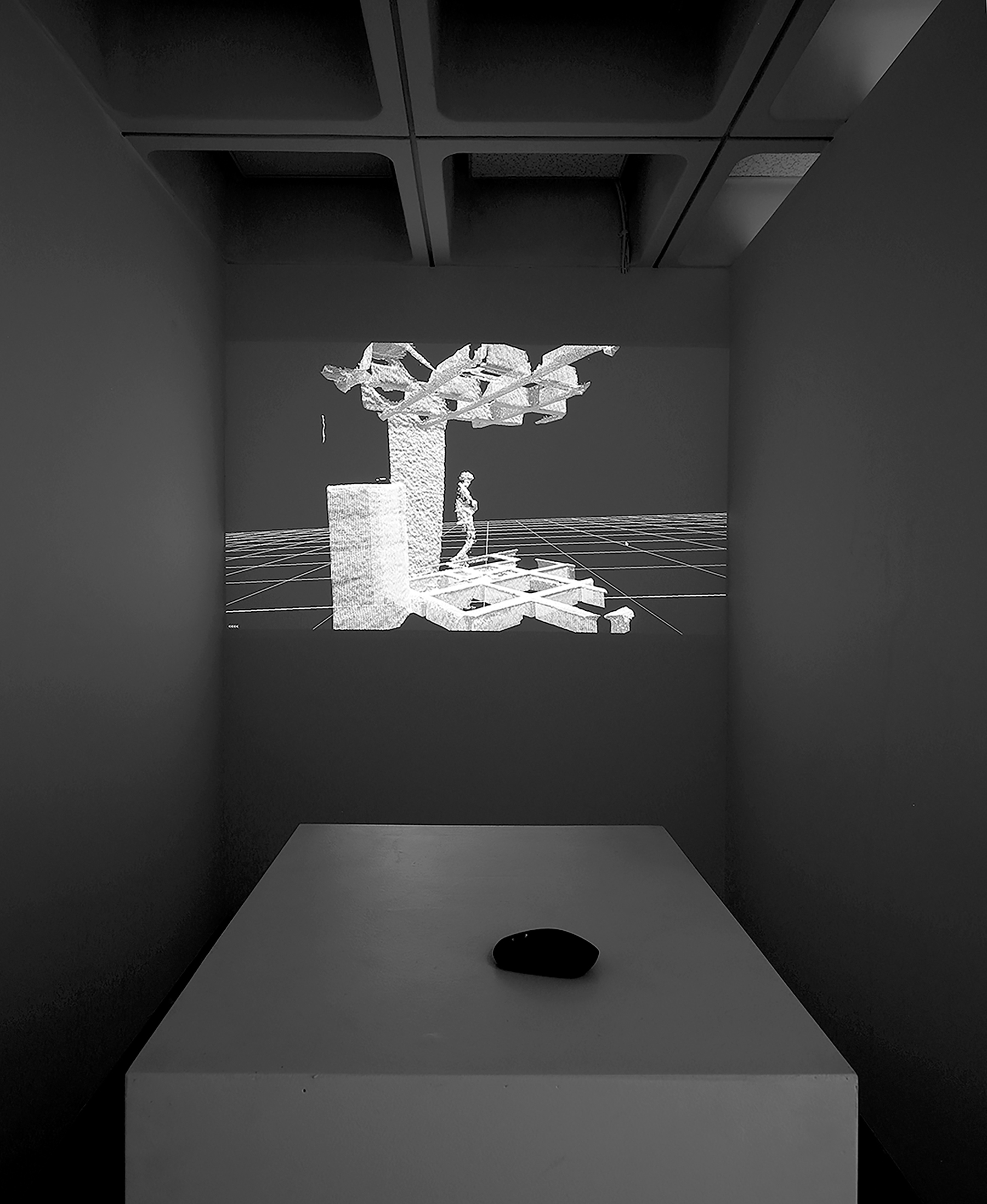

JODI, And/Or Grid 3D Scans, 2018. 3D scans on custom website, computer, projector, mouse. Installation view, Show #31: JODI, And/Or Gallery, Los Angeles, May– September 2018. Courtesy of the artists and And/Or Gallery.

Almost anticipating this trans-humanist conundrum, JODI inserts a bit of fun in these images, capturing not just incomplete versions of scanned bodies but bodies that have been captured looking at art. This double act of mirroring as a coup de grâce is quite stunning. A shattered human looking at a smashed sculpture! Simulacrum considering simulacra! This Möbius strip of referentially might be laugh-out-loud funny if it weren’t so frightening. There is something deeply concerning about considering oneself in this context, as if confronting one’s own wrecked data was akin to meeting one’s future cadaver, or, perhaps, coming face to face with the Minotaur and recognizing oneself.

Standing and considering these uncanny protagonists, I had the feeling I was observing some kind of surveillance footage of a primitive ritual or hunt, with the various fractured figures hovering around an abstracted prey. It was as if the incompleteness of the body and the ambiguous space made them less human and more animal and as such mirrored a similar feeling in me to want to ingest the images in lieu of greater legibility. Perhaps this is what Steyerl means to evoke with her epistemic separation? Not so much trans-humanism as a revelation of inter-speciation. Again, with hints of Greek myth, the virtual space elicits a sense of taboo, alluding to the Minotaur’s origins and our own.

This disconcerting “in-betweenness” was the subject of the final room, wherein JODI has installed And/Or Grid 3D Scans (2018). In this series of scans, the And/Or Gallery visitors who were scanned at the opening are shown in the virtual space of the cardboard grid. Similar to Scan Journal (213D.org) #artgallery 3D scans, these images possess a more poignant affect because they capture the viewers alone without any discrete art objects to give them orientation. The cardboard Cartesian model crystallizes the logic of the stage-like environment: it is a literal architecture that will become a scanned digital environment, i.e., it is a metaphysical model and digital trap. This virtual reality, as architectural container designed to house an atomized and chaotic digital copy of the subject that perceives it, highlights the instability of the data, suggesting that the incomplete scan is every bit as vital to our contemporary imaginary and pursuit of knowledge as was techne in pre-classical Greek philosophy.

This relationship between chaos and techne, of locating and visualizing oneself in the environment as a means of both speculative imagination and systematic control, seems to be the leitmotif of the show. JODI repeatedly uses scanning technology, whether Wi-Fi or LIDAR, to ping back and forth between the subjects and their perceived environment. Scanning, in this respect, echoes the way the power to conceptualize space both precipitates the maze and also helps metaphorically to solve it. JODI’s incomplete scans, mods, and websites, like latter- day maps, establish a powerful basis for navigating this post-internet era by remaining rooted in the story of the labyrinth, thereby unwinding our place in the cosmos and opening what Steyerl argues is the “fictional backdoor of the image.”32 One hopes this digital threshold, cunningly crafted, can serve as a medium of translation, as well as transformation, and not just a more elaborate prison.

Nick Herman is an artist and writer in Los Angeles.