Feminists taking on sexism and violence against women is nothing new, but the Internet and social media have transformed the circulation and effects of that violence and sexism, along with the visibility and nature of the discourse around those issues. Andrea Bowers’s multi-media installation #sweetjane (2014) and Emma Sulkowicz’s Mattress Performance: Carry That Weight (2014–15) are two examples of recent artworks that address social media, as well as the violence that permeates our culture and often surrounds the tellers of truth. In the former, Bowers examines a 2012 attack on a sixteen-year-old girl who was abducted and raped by star high school football players in Steubenville, Ohio. In particular, the work considers how social media contributed to the attack and later provided evidence against the attackers. Bowers’s project also highlights the involvement of a group of “hacktivists” going by the name Anonymous, who advocated for the rape survivor, in contrast to her further silencing and victimization by social and mainstream media. The work speaks to the lack of accountability for hate speech and other forms of aggression in the space of social media, which is often perceived to be outside of the space of an ethical mainstream (both by those who use it and those who don’t). In an action that circulated prominently in media in a different way, Columbia University art student Emma Sulkowicz carried a dorm mattress around with her on campus at all times for over eight months in protest of the university dismissing charges against her alleged rapist and allowing him to remain on campus during and after the hearings. In addition to these recent artworks, Feminist Frequency is a thought-provoking web-based project that aims to educate and provide constructive critiques of sexism and violence against woman in popular culture. In response to her insightful observations, Feminist Frequency’s Anita Sarkeesian has faced persistent threats in both the virtual and real world. All of these projects aspire to the work of consciousness raising (CR), although in the current moment it takes forms that are necessarily different from the intimate circle of 1970s feminist CR exercises.

Through a documentary-style video and large-scale photographs, Bowers’s #sweetjane tells the story of Jane Doe, whose attack was broadcast on social media as it happened. These tweets and posts were later discovered and captured by Alexandria Goddard, a concerned adult crime blogger formerly from Steubenville, who, after the perpetrators were arrested, picked up on the story and brought it to a broader audience. Steubenville is an industrial town with a depressed economy and a football-centric culture that revolves around the high school’s Big Red team. The victim was from a nearby town in West Virginia, where she attended a private religious school and lived in a middle class neighborhood.1

Andrea Bowers, #sweetjane, 2014. Installation view, Pomona College Museum of Art, Claremont, CA. Single-channel HD video (color with sound) and mural installation. Duration: 33:48. Courtesy Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer.

The #sweetjane video, a mix of stills of the Ohio town and media footage culled from TV and online sources, is carefully selected to give an overview of the situation and the significant role that social media played in both the attack and its eventual prosecution. While watching commentary by onlookers of the attack and an image of the perpetrators holding the girl’s limp body between them, it is deeply disturbing to see how little compunction the boys have about circulating crude comments and images of their victim, who was intoxicated and unconscious during much of the ordeal. They took her inability to give consent as license to do as they wished to her. Laughing, one bystander speaks of her as “dead.” While clearly aware of the ongoing attack, he did not intervene and was not prosecuted. Ultimately, two boys who were most directly involved, quarterback Trent Mays and wide receiver Ma’lik Richmond, were convicted and sentenced to serve two years and one year, respectively. One cannot help thinking that this terrible incident is a failure of society, of the community that surrounds these young men, and that provides the matrix within which such a crime is possible. This is the position of a member of the activist group Anonymous, who posted a video on YouTube several months after the attack threatening all involved with doxxing if they did not take action to prod local authorities and the community to hold Jane Doe’s attackers accountable for their actions. (Doxxing is a common online term to describe the deliberate act of distributing an individual’s personal documents, making them vulnerable to further attacks online and off.2) This video was immediately picked up and posted on a Steubenville football fan website by a sympathetic hacker. It’s unnerving that the pursuit of justice relied on the vigilante tactics of Anonymous, whose spokesperson in the broadcast wears a Guy Fawkes mask. Despite Anonymous’s creepy computer-manipulated robotic voice, the message was undeniably articulate and ethical, coming across as the voice of reason compared to the local mainstream media’s sympathetic attitude toward their star football players. This attitude is epitomized by the comments of one female news reporter, who dramatically laments the diminishment of the football players’ bright future in her reportage, shockingly ignoring the victim’s trauma or future prospects. Even the victim’s anonymity, intended to protect her, dehumanizes her in comparison to the boys, who are named in reports. Interviews with town residents and commentary by local law enforcement convey a “boys will be boys” attitude, describing them as “stupid” rather than “criminal” (the implication being that they were stupid because they were caught, not because of what they did). The juxtaposition of the broad range of responses in Bowers’s video begins to reveal the inherent social biases that led to the crime, including dynamics of sexism, race and class.

Andrea Bowers, Courtroom Drawings (Steubenville Rape Case, Text Messages Entered As Evidence, 2013) (detail), 2014. Installation view, Pitzer College, CA. Marker on paper; 56 parts, 40 x 33 inches each. Installed dimensions variable. Courtesy Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer.

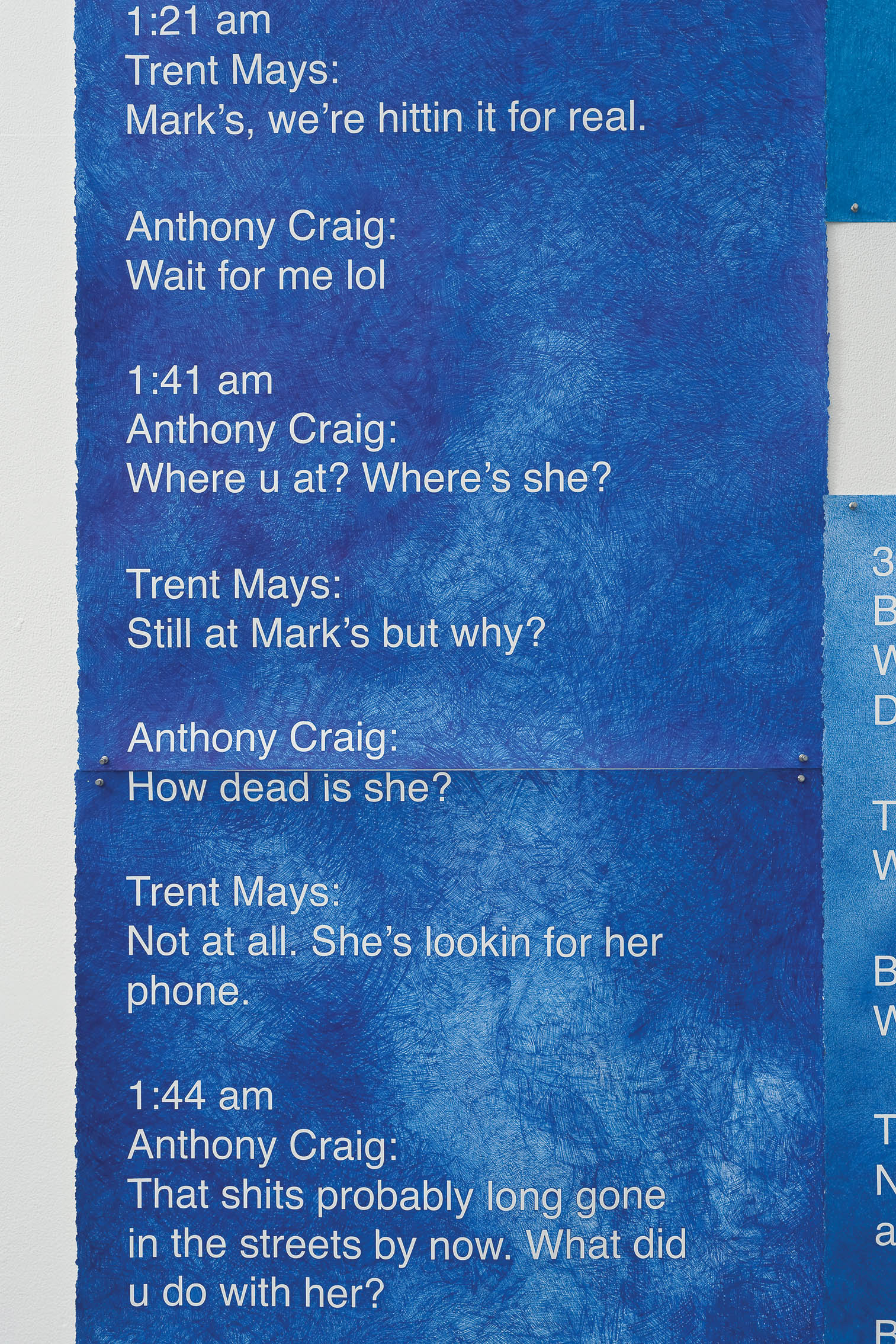

Andrea Bowers, Courtroom Drawings (Steubenville Rape Case, Text Messages Entered As Evidence, 2013), 2014. Installation view, Pitzer College, CA. Marker on paper; 56 parts, 40 x 33 inches each. Installed dimensions variable. Courtesy Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer.

#sweetjane was presented in a tandem exhibition at Pomona College Museum of Art and in the art gallery at neighboring Pitzer College, in Claremont, California, in 2014. At Pomona, the video projection was flanked by mural-sized photographs of activists who rallied to support Jane Doe outside of the courthouse during the trial (many wearing Guy Fawkes masks in solidarity with Anonymous). In the Pitzer College gallery, Bower displayed Courtroom Drawings (Steubenville Rape Case, Text Messages Entered As Evidence, 2013) (2014), a series of drawings that reproduced text messages from the rapists and the victim, gathered by Bowers and two journalists who transcribed them during the trial, where they were presented as evidence. Bowers’s drawings are laboriously rendered in marker, with white letters against luminescent blue backgrounds, reminiscent of computer screens and roiling skies. Papering the walls of one gallery in staggered columns, they operate as a kind of contemplative memorial, where viewers may sit on a bench and read, reflecting on the collusion of the perpetrators and the distress of the victim as glimpses of what happened appear in fragments of dialogue.

One can ask about the effectiveness of #sweetjane, or any other artwork, as activism, critique, or pedagogy. A good deal depends on how and in what context the work is presented. In the rarefied space of the art gallery or museum, pitfalls range from aestheticizing and capitalizing on trauma to preaching to the converted, indifferent audiences, or perhaps even more problematic, a circumstance where viewers might feel they have fulfilled their obligation to attend to these issues simply by viewing the installation.3 The latter potentially parallels the complicity that we as citizens enact when we ignore the persistent inequity, violence, racism, and sexism that we encounter in our daily lives. In Bower’s case, her video’s accessibility online via Vimeo and the presentation of her project on a college campus, where the issue of sexual violence is highly pertinent, contribute to the work’s political effectiveness.

Emma Sulkowicz’s highly publicized Mattress Performance: Carry That Weight converts the artist’s declared experience of rape and injustice into an act of self-advocacy and activism. Sulkowicz’s case is perhaps more typical of the average rape case, where there was no clear objective evidence, such as the social media trail in the Steubenville case, to support the victim’s accusations. What social media evidence there was—seemingly cordial Facebook posts and texts between Sulkowicz and her accused rapist from before and after the attack—were ambiguous and were used against Sulkowicz in the university hearings. Both cases are typical in that the victims knew their attackers (which happens in 78% of reported rapes), there was a delay in the victims reporting the rape, and no rape kits were analyzed.4 Unfortunately, in the “blame the victim” default that most often occurs in rape cases, these are all factors that are held against the victim and that result most often in a “he said/she said” scenario. Outraged and distressed by what she experienced as intrusive and incompetent handling of her case by Columbia University, Sulkowicz turned to her art practice and public protest as a means of speaking out and making her experience visible. Visibility is the real issue here. And unlike Jane Doe in Steubenville, who as a minor was represented by others, Sulkowicz embraces her agency to represent herself. In this regard, Sulkowicz’s performance of bearing the weight of the mattress on her back for nearly nine months makes visible the real effects of rape on the victim with great economy in a literal collision of strength and burden. While some speculate that her claim of rape is false and that Sulkowicz is seeking attention, it is hard to believe that anyone would seek notoriety under such terms, especially given that the response that one commonly receives after reporting rape is largely condemnation or indifference. Furthermore, what does it say about our society when we imagine that a young woman’s hopes for attention and agency would be channeled through false claims of rape? Given the low statistical levels of such false claims, it would seem that we are a society in denial. It would be more productive to see situations like Sulkowicz’s as indicative of a bigger social problem. This is supported by the public response to her performance, which galvanized a “carry that weight together” campaign in which sympathetic students at Columbia rallied to help Sulkowicz. The campaign later went viral, extending to symbolic mattress carrying at other college campuses, as well as a more formalized website and eponymous activist campaign. The evolution of this movement—as with other social justice movements fueled by social media, such as Black Lives Matter—is both inspiring and sobering, because it makes clear the immense power of the Internet and social media to assert an unprecedented level of influence, whether the cause is just or not.

Columbia University students rally to support survivors and protest the university’s treatment of sexual assault cases, September 12, 2014. Photo: Kiera Wood. Courtesy Columbia Spectator.

Soon after her graduation, Sulkowicz posted another artwork online, entitled Ceci N’est Pas Un Viol (This is Not a Rape) (2015). The work is a stand-alone webpage that includes a brief introductory text and an explicit video of her enacting a staged sexual encounter with a male actor in which there appears to be a shift from a consensual act to a nonconsensual one as the sex unfolds. The sequence of events resembles the descriptions that Sulkowicz has given of her rape, and the video, filmed from cameras placed high on four sides of a dorm room, has the appearance of surveillance. The work engages with online discursive spaces and audiences as an important site of reception in the present moment. Within that space, Sulkowicz raises the question of audience accountability for the construction of art and culture, as well as social values. In the text for Ceci N’est Pas Un Viol, she states: “You might be wondering why I’ve made myself this vulnerable. Look—I want to change the world, and that begins with you, seeing yourself.” She continues to ask a series of questions, beginning with:

—Are you searching for proof? Proof of what?

—Are you searching for ways to either hurt or help me?

—What are you looking for?5

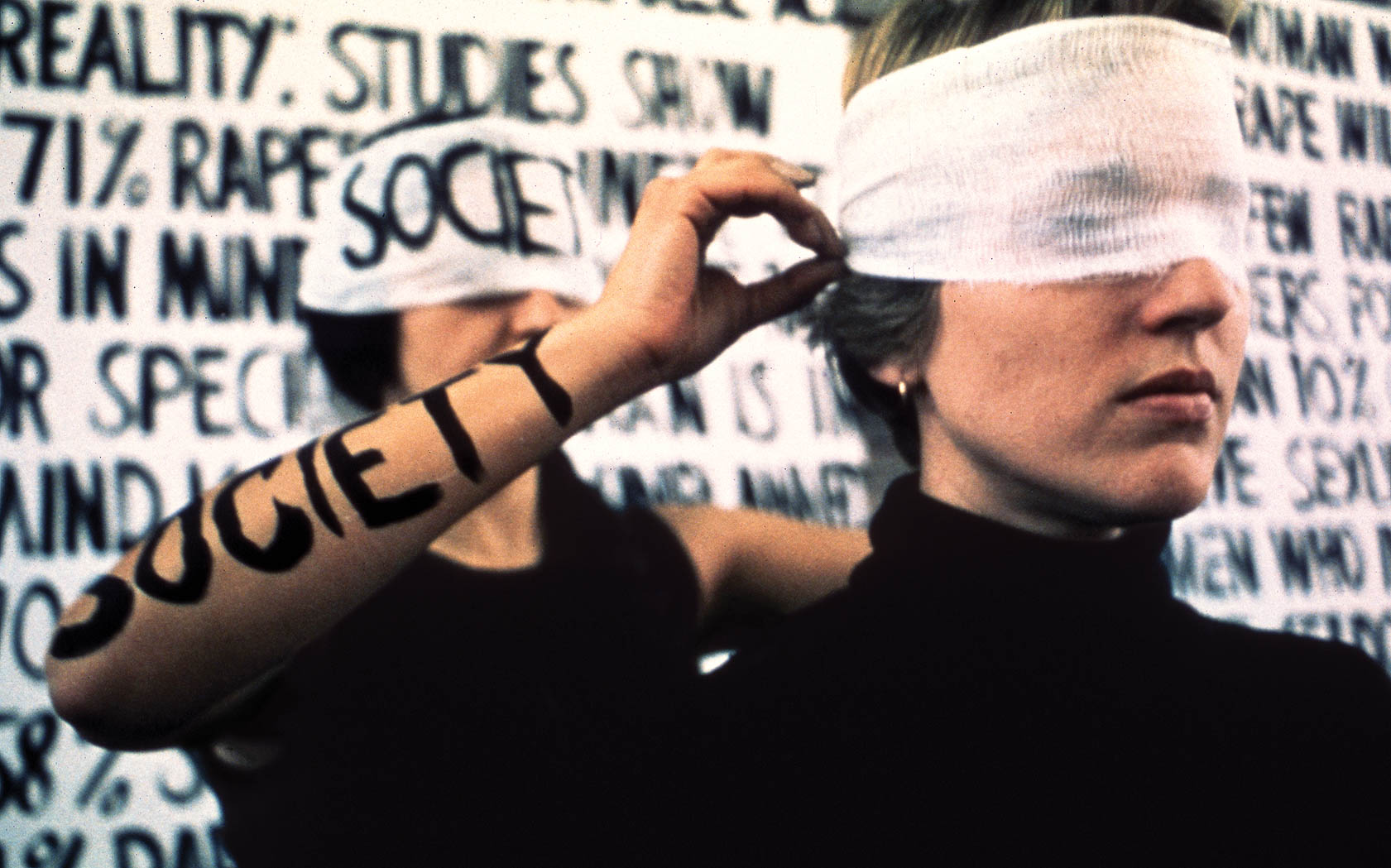

It is no surprise that, along with a number of earnest responses to the artist’s questions and guidelines, a high percentage of posted responses are sexist, crude, and cruel. As a work that employs both deliberate staging and radical vulnerability to highlight the tenuous self-restraint that guides normative social behavior, this work by Sulkowicz bears comparison with Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece (first performed by Ono in 1964). In this Fluxus work, members of the audience are invited to approach the performer, who sits motionless, and cut a piece of her clothes to take with them, using scissors set on the stage beside her. As Cut Piece unfolds, one becomes keenly aware of the intimacy and potential violence within that interaction between audience member and performer, along with the recognition of a vacillation between objectification and empathy as a witness to the performance.6 Ana Mendieta’s shocking and powerful Untitled (Rape Scene) (1973) also comes to mind as a performance work that similarly uses identification and catharsis as a means to both process an unspeakable act of violence and place viewers in a position of witnessing and accountability through encountering a live performance (as Mendieta’s fellow students did when they arrived at her studio and found her naked and bloodied, in a scene that recreated a rape/murder reported in the press). As provocative as Sulkowicz’s project may be, she is certainly not in uncharted territory. Her protest enacts a common feminist necessity of reviving and asserting experiences and histories that go against the grain.

Suzanne Lacy and Leslie Labowitz Starus with assistance of Bia Lowe, In Mourning and In Rage performance, 1977. Holly Near singing on the steps of Los Angeles City Hall. Photo: Maria Karras.

Bowers’s and Sulkowicz’s projects echo the efforts of other earlier feminist projects, such as Suzanne Lacy and Leslie Labowitz’s In Mourning and In Rage (1977), which used the tactics of political street theater on the steps of city hall to protest the Los Angeles Police Department’s failure to apprehend the Hillside strangler, a serial rapist and killer. The orchestrated media event was documented in an art video. The video has circulated widely since 1977 and was always intended, like Bowers’s installation, as a means “of bearing witness to unspeakable facts that have been formerly silenced.”7 As a large-scale collaborative activist performance, In Mourning and In Rage followed another significant work by Lacy on the subject of rape. For this work, entitled Three Weeks in May (1977), Lacy collected daily rape statistics from the LAPD and stamped their locations on a map of the city. A second map represented advocacy organizations and self-help activities planned over the period of three weeks as sites of resistance to the status quo.8 These works, along with other projects, such as Take Back the Night (Lacy and Labowitz, 1978) and From Reverence to Rape to Respect (Lacy, Labowitz, Kathy Kauffman, and Claudine King, 1978), sought to make visible and speak out against ongoing violence against women of all walks of life.

Suzanne Lacy, Three Weeks in May performance, 1977. Photo: Suzanne Lacy.

Leslie Labowitz Starus, Myths of Rape performance, 1977. Part of Three Weeks in May, by Suzanne Lacy. Photo: Suzanne Lacy.

In Mourning and In Rage evolved out of Lacy and Labowitz’s work in the Los Angeles Women’s Video Center, part of the Woman’s Building alternative educational space in Los Angeles (1973–91). Deeply invested in feminist ideals and in non-hierarchical modes of process and communication as a means to defuse patriarchal oppression, its pedagogy was based on validating women’s lived experiences as premises for self-understanding and growth. Consciousness-raising sessions, which were conducted with women sitting a circle, enacted this ideal physically, in real space, and were one of the fundamental forms of self-exploration and learning at the center. Many hours of the Los Angeles Women’s Video Center archive record raw exercises in self-discovery and role-playing games. Some of these experiences ultimately informed more fully conceptualized art works and performances. But consciousness raising itself—often a messy, discordant, and painful process—was considered inherently purposeful and worthwhile.

The multi-media installation Equal Time in Equal Space: Women Speak Out About Incest (1980) (often referred to as ETES), is an example of a fully realized work originating at the Woman’s Building that productively employed a tension between mediation and physical presence to examine the taboo subject of incest.9 Via technology, this complex work offered a buffer of protection to incest survivors and at the same time insisted on a physically present engagement from its viewers as witnesses. By all accounts, the generative, safe environment of the Woman’s Building made a discussion of invisible and controversial issues such as incest and rape possible among the women who gathered there. And significantly, ETES, like In Mourning and In Rage and other similar projects, had impact because it expanded to an audience beyond the parameters of the Woman’s Building. Lacy, Labowitz, and Angelo were keenly aware of the need to step out of the safer space of the Woman’s Building and push for broader public recognition of these problems. In other words, not only was the personal political, the personal was public, in the sense that persistent violence against women derives from broader social structures of oppression, and these structures cannot be challenged and dismantled without a public intervention.

Equal Time in Equal Space, 1980. Collaborative video installation directed and produced by Nancy Angelo as part of The Incest Awareness Project, 1980. Photo: Bia Lowe. Courtesy the artists and the Woman’s Building Image Archive.

Nearly forty years later, it is disheartening that it still is necessary for women and artists to articulate the blatant and subtle ways violence is perpetrated against women in American society. At the same time, the media landscape has changed, with new virtual outlets for such violence and sexism to circulate, often unchecked. While the media context in the 1970s consisted of radio, the printed press, movies, and television, and one’s audience was local or perhaps national, the boundaries have expanded well beyond that today. In their generation, Lacy and Labowitz used the strategies of art and activism, along with the then-newly accessible technology of video, to speak back to popular media in its own language and as a means to raise awareness in a broader audience.

In our age, technology offers new opportunities for activism, yet we also face a baffling lack of social mechanisms for accountability, particularly in social media and online space, which offer unique conflations of private and public space that we as a society have yet to figure out how to address. Although undoubtedly mitigated by accessibility and the agendas of varied stakeholders, the forum of social media offers unprecedented opportunities for the spread of a critical scope that engages oppressions. It has the potential to amplify the voices of minority or oppressed positions, share information more transparently, and demand accountability. It can also be a tremendously unsafe space in which to engage in social exchanges or civic dialogue. All too often, harassment online is seen as an inextricable condition of online culture, but as Wired journalist Laura Hudson points out, it is not. Acknowledging that people spend an increasing amount of time socializing and working online, she calls for virtual communities to enforce accountability for harassment and civilized social norms in a manner that is at least as stringent as those in the real world.10 She criticizes Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter, a few of the social media sites most frequented by Americans, for not doing nearly enough.11 Hudson also cites examples of gaming communities that have made great progress in reducing harassment. In particular, she applauds Riot Games, the publishers of the hugely popular battle-arena game League of Legends (which has more than 67 million active players each month) for initiating innovative community-wide reforms that dramatically reduced online harassment. That’s a good place to start. However, the greater project of how to create a society that abhors violence against women rather than condones it must continue, because as Bowers’s #sweetjane project reflects, the mechanisms that exist in both the real and so-called virtual world to protect women and minors from sexual harassment and violence are still inadequate.

In October 2014, feminist commentator Anita Sarkeesian cancelled a speaking engagement at Utah State University due to death threats made against her and her audience. In a disturbing example of harassment that begins online and then spills violently into the “real world,” one of the ominous emails, addressed to the university, promised “the deadliest school shooting in American history” and was signed with the name of a long-dead mass murderer. A cultural critic and avid gamer whose main platform is the Feminist Frequency channel on YouTube, Sarkeesian is a controversial figure, drawing fierce attacks from defensive gamers and designers because of her no-holds-barred feminist analyses of video games and entertainment media.12 She has been a frequent target of death and rape threats. However, this was the first time that she felt compelled to cancel a public talk. The severity of the threat, coupled with the fact that Utah law made it impossible for campus police to prevent people with weapons from entering the campus venue, made the seriousness of the risk obvious.

The anonymous and ominous threats that shut down Sarkeesian’s talk in Utah are yet another move in a history of silencing of women. As the visible spokesperson for Feminist Frequency, Sarkeesian has become the main target of responses to the channel, especially the most aggressive negative ones. (Jonathan McIntosh, Sarkeesian’s male collaborator, is rarely mentioned in the press or in online commentary, positively or negatively.) For those not familiar with the vast world of video games, episodes in the “Tropes vs. Women in Video Games” series of Feminist Frequency, which confirm the pervasive presence of sexism and violence in many video games, will be both eye-opening and disturbing. The series also makes the case that a critique of sexism and gender stereotypes does not exist in isolation from other ideologically produced damaging stereotypes, including racist ones. Feminist Frequency insists that such visual culture manifestations are symptomatic of an underlying social dynamic that needs to be openly acknowledged and questioned. That social dynamic might best be described by bell hooks’s term “white male supremacist patriarchy,” which hooks uses as shorthand for “the interlocking systems of domination that define our reality.”13 Feminist Frequency’s head-on critical engagement with popular culture is consistent with hooks’s conviction that, whether talking about race, gender, sexual orientation, or class, popular culture is “the primary pedagogical medium for masses of people globally who want to in some way understand the politics of difference.” 14Presenting itself as social media, Feminist Frequency extends a critique of popular culture into more esoteric areas such as video games, which in their online form are vast forums of social exchange that are unique to our time.

Feminist Frequency, Ms. Male Character: Tropes vs. Women in Video Games, 2013. Stills from video webseries episode, 25:01. © Feminist Frequency.

Sarkeesian believes the backlash by fellow gamers is directed at women like herself—women who have played games their whole lives and who are interested in how women are represented in that space—because they are challenging the status quo of gaming as a male-dominated space.15 After all, TV and video games are amongst the greatest American entertainment pleasures and escapes, not to mention profitable businesses. Consumers and producers often don’t want to examine or be held accountable for how these forms of entertainment might contribute to the perpetuation of “white supremacist capitalist patriarchy.” It is interesting to note that while the majority of this menacing and vitriolic backlash toward Sarkeesian and Feminist Frequency comes from male gamers and commenters, there is no shortage of critics among her fellow cyber-feminists, who criticize Sarkeesian’s web-celebrity status (i.e. that she is being provocative to get attention mainly for her own benefit) and characterize FF as didactic and reductive. Feminist dialogue online is thriving and diverse, but also dauntingly contentious and divided, with complex dynamics that are too involved to take on here.16 I also encountered many statements by female gamers who defended fellow male game designers and gamers as “nice people who did not hate women.” These women were missing the point, which is that sexist bias is inherent in a patriarchal system, irrespective of whether individuals are “good people” or not. These women and the men they defended had internalized this bias to the point where they could not see their own complicity in perpetuating a value system that demeans women and represents them as sexual objects. It is precisely in such moments that hooks’s insight that all oppressions are interlocking ideological values in a system that cannot effectively be critically parsed, much less disrupted from any singular approach, becomes valuable and necessary. As the recent cases of Michael Brown and Eric Garner have shown, there are similar dynamics of violence, objectification, and devaluation in the representation and treatment of people of color. As with sexism, these dynamics play out in popular culture as well as in the “real world.”

Alluding to Magritte’s famous semiotic painting, Le trahison des images (Ceci n’est pas une pipe) (The Treachery of Images [This Is Not a Pipe]) (1929), Sulkowicz’s title posits that the most contested space as a woman in American culture is the space of representation. In popular media we are inundated with rape and violence against women as entertainment. As entertainment—as “fiction” or “play” or “fantasy” —these actions and images are dismissed as innocuous or excusable, i.e. “these are not rapes, they are merely representations of rapes.” However, as Magritte’s painting succinctly embodies, representation and language are slippery at best, with the “real” residing somewhere paradoxically within and beyond them. Just as second wave feminists demanded agency for women over their own bodies and sexual freedom (among other political and cultural demands), Ceci N’est Pas Un Viol registers that battle continuing into the realm of the virtual. As a whole, the project is self-contradicting, angry, courageous, and replete with pain and loss. Sulkowicz’s text comes across as verklempt, a barely controlled rant, not fully parsed or edited. This represents a state of mind that echoes with the questions and inner conflict that I feel as I write this essay and seek to find balance between sounding convincingly analytic about these artworks (so that my analysis might be taken seriously and not dismissed as “old news” or as hysteria, that old stand by) when the ongoing reality of the social space I live in makes me outraged and fearful, both for myself and other women—including Emma Sulkowicz and Jane Doe. Within this inner struggle is the recognition of a panopticon of the imaginary that silences women more powerfully than online threats and harassment.

This more insidious version of repressive ideologies is what both Sulkowicz and Bowers seek to represent and challenge. We place many women in our society in such a head space—where they have been abused, abandoned, not listened to. (Here I think of the thirty-five plus women who brought charges of sexual assault against actor Bill Cosby with no justice rendered and, from a more global perspective, of the nearly three hundred schoolgirls kidnapped into sexual slavery by Boko Haram in Nigeria in 2014.) It’s no wonder how few victims of rape and violence report to the authorities. In Ceci N’est Pas un Viol, Sulkowicz insists on her own right to represent herself, for better or worse. She addresses her audience directly and challenges them to confront their own complicity in engaging with representations of violence and voyeurism as entertainment. More so than the Surrealist label usually ascribed to Magritte’s Ceci n’est pas une pipe, Sulcowicz’s Ceci N’est Pas un Viol resonates with Dada artists’ response to the absurd inhumanity and abhorrent violence of WWI: How to counter extreme trauma except with a radical gesture of protest beyond sense? How does one represent a scream?

Karen Dunbar is an artist, writer, and educator who lives and works in Los Angeles.