When she talks I hear the revolution

In her hips there’s revolution

Where she walks the revolution’s coming

In her kiss I taste the revolution

—Bikini Kill, “Rebel Girl”

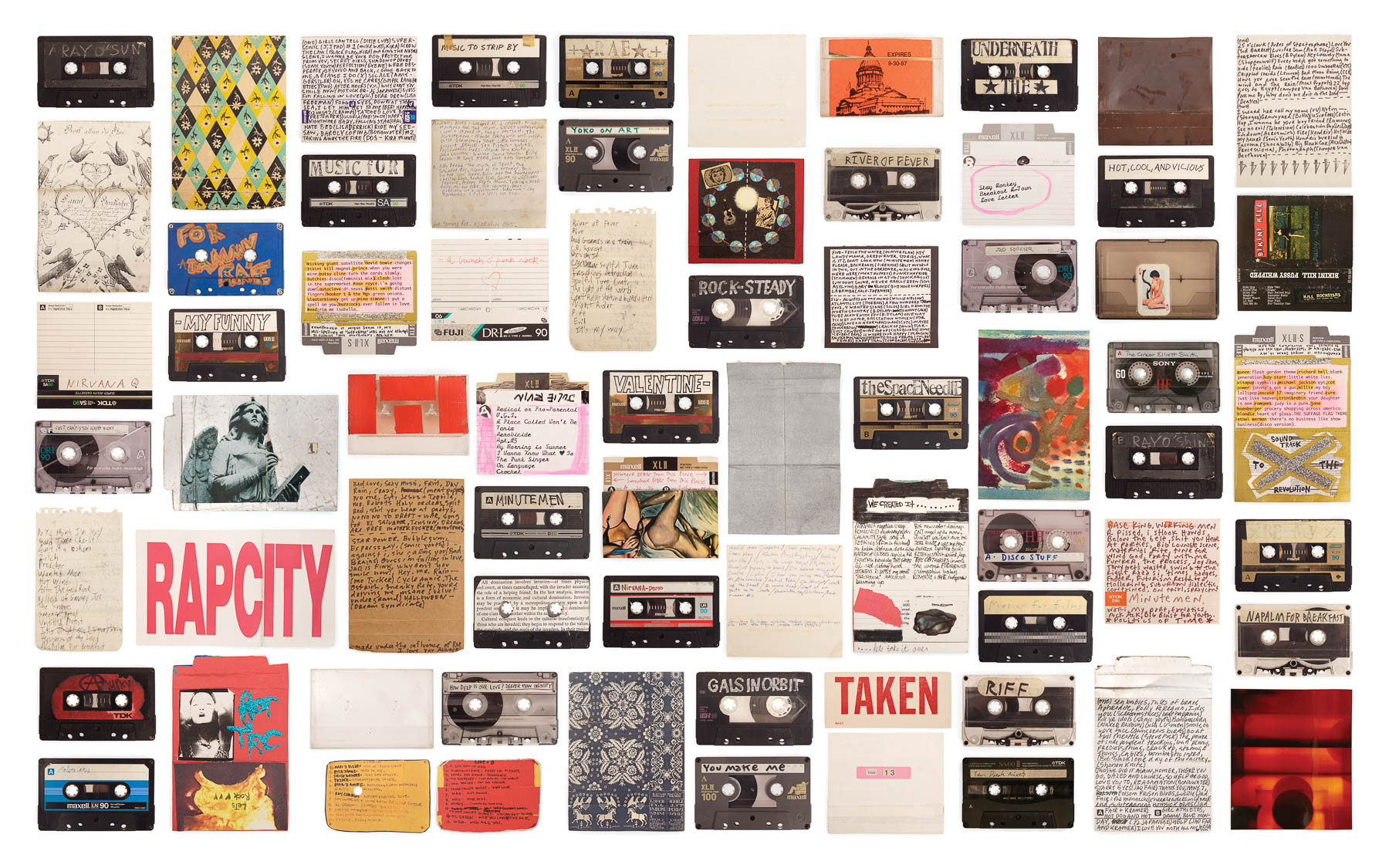

When Bikini Kill’s “Rebel Girl” first appeared on the album Pussy Whipped in 1993, the band was already the acknowledged ringleader of the riot grrrl movement.1 Fifteen years later, Tammy Rae Carland’s photograph One love Leads to another (2008) honors the place of the band and the album in music history. In the photograph, Bikini Kill’s iconic Pussy Whipped is the only commercially produced cassette cover visible within a neat grid of seventy homemade cassettes and sleeves from Carland’s personal collection. Ten years senior of most grrrls’, Carland herself was a beacon of the movement. In college at Evergreen State in Olympia, Washington, in the early 1980s, she formed the band Amy Carter with Kathleen Hanna (later of Bikini Kill and Le Tigre), after which she began publishing the pioneering zine I [Heart] Amy Carter (1986 to 1992), while in art school at the University of California, Irvine. In 1996, she co-founded the punk/feminist/queer record label Mr. Lady Records (1996–2004), which represented The Butchies and Le Tigre, among others. The label provided a production and distribution system for a generation of queer and feminist women in punk, and its impact on rock was ultimately exponential.

Tammy Rae Carland, One love Leads to another from the series Archive of Feelings, 2008. Inkjet print (AP); 52 3⁄8 x 34 1⁄8 inches, framed. Courtesy of the artist and Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco.

Carland’s personal archive of tapes is a particularly emblematic window onto the history of riot grrrl and the other musical genres with which it is intertwined. Labeled in magic marker, the drawn, collaged, or recycled covers of the tapes in One love Leads to another bear titles such as “Yoko on art,” “Music to strip by,” “Just can’t stay happy today,” and “You make me.” Each mixtape is a token of a specific time, place, and feeling exchanged between friends or lovers. In photographic form, the notes magnetically suspended on each tape cannot deliver their essential auditory experience, the corresponding memories, or the visceral sensation of listening to music. Instead, Carland’s photograph is a perpetual pause to consider the potential of her personal archive, our own similar collections, and the distance between experience and representation.

This archival conundrum is at the core of Alien She.2 The exhibition, which takes its title from a Bikini Kill song, presents a handful of visual artists involved in the 1990s punk feminist riot grrrl movement. It poses a valuable question: How do we effectively remember the marginalized history and experiences of riot grrrl culture and activism? How do we catalog the stories of thousands of women and men making music, art, friends and allies in explicit opposition to patriarchy and capitalism, in bars and basements, through music, mixtapes, and zines? The challenges inherent in historicizing these stories are many: the grassroots nature of many of the movement’s gatherings and communities, the ephemeral nature of its artifacts, its prioritization of personal and affective experience, the commercial cooptation of the riot grrrl image, and the nostalgia that blurs our vision of a fabled revolutionary community.

Curators Ceci Moss and Astria Suparak eschew the traditional historical exhibition in favor of a retrospective look that is firmly positioned in the present. The exhibition emphasizes work made in the last ten years, well after riot grrrl’s heyday. A collection of riot grrrl ephemera is exhibited alongside recent works by seven North American artists: Ginger Brooks Takahashi, Tammy Rae Carland, Miranda July, Faythe Levine, Allyson Mitchell, L.J. Roberts, and Stephanie Syjuco. An antechamber of zines, posters, and playlists from the 1990s is followed by a section dedicated to each of the artists; all but two were born around 1975, just in time to hit the peak of riot grrrl in their late teens. (The exceptions are Carland [b. 1965] and L.J. Roberts [b. 1980].) The exhibition didactics discuss the archive and each artist’s body of work relatively independently, rather than articulating an overarching curatorial argument.

Installation view of select zines and distribution catalogs, 1991–2013, in Alien She, Orange County Museum of Art, Newport Beach, CA. Includes 276 original zines and 27 handleable reproductions. From the personal collections and archives of The Riot Grrrl Collection at the Fales Library & Special Collections, NYU; Elisa Gargiulo; Sara McCool; Ceci Moss; Maaike Muntinga; Mimi Thi Nguyen; Astria Suparak; and Cookie Woolner. Photo: Chris Bliss Photography.

Three photographic series by Carland introduce the contemporary portion of the show. Her series Archive of Feelings includes a photograph that depicts the dedication pages of sixteen books from Carland’s personal collection, such as “To F…for September 2nd,” and “This book is dedicated to my tattooist.” These intimate moments set the tone for the relationships between lovers and friends that surround the work. As the exhibition unfolds, the tight-knit network among the artists becomes increasingly apparent. Carland references queer theorist Ann Cvetkovich through the title of this series; Cvetkovich, in turn, discusses Kathleen Hanna’s music in her book of the same name; and Hanna’s Bikini Kill song “For Tammy” is named for Carland. The myriad relationships within this alliance of artists (for example, Takahashi was a member of MEN with Johanna Fatemen, who calls Miranda July her “best friend from high school”3) demonstrate how significant and unifying this music, culture, and community were for a generation of feminist and queer artists.

Cvetkovich’s An Archive of Feelings is a fruitful reference, as it explores the particular way that many riot grrrls formed their communities around the traumas of girlhood.4 Lesbian community is Cvetkovich’s primary concern in her book, which elucidates the ways in which women have formed emancipatory culture and activist communities around sexual, physical, and emotional traumas. It’s easy to see this in riot grrrl culture. Cvetkovich recounts a show at Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival (MWMF) in which Lynn Breedlove of the band Tribe 8 strapped on a dildo, then cut it off.5 Tribe 8’s “Frat Pig” exposes gang rape,6 and Bikini Kill’s “Liar” condemns domestic abuse.7 In these and many other examples, riot grrrl song lyrics and performances explicitly address the traumas of womanhood—rape, violence, and all sorts of debasement, disenfranchisement, and heteronormative strictures—and the shame, anger, and solidarity they can induce.

L.J. Roberts, Gay Bashers Come And Get It, 2011. Banner in use during the Dyke March in New York City. Jacquard-woven cotton and Lurex, hand-dyed fabric, crank-knit yarn, and thread. Graphic appropriated from a poster designed by Matt Height, silkscreened at Queeruption (1999) at DUMBA, Brooklyn, and used as an album insert for queercore band Limp Wrist. Photo: Blanca Garcia, 2011. Courtesy of Blanca Garcia.

In the recent work, the unmasked rage and frank indictment of misogynistic acts are softened with subtler strategies. L.J. Roberts’s protest banners, for instance, use home crafting tools like knitting machines and sparkly yarn to create fey objects with sexually and physically explicit messages like Sisters Are Doing It For Themselves and Gay Bashers Come And Get It (both 2011). The gallery installation unfortunately enfeebles these banners by leaning them limply against big white walls. A small photograph of the pieces in action is much more powerful. The photo shows Roberts raising the Gay Bashers Come And Get It banner next to a man holding a “JESUS saves from HELL” sign on the steps of the New York City Public Library. The man’s black-on-white, machine-printed cardboard sign contrasts sharply with Roberts’s tasseled, knitted banner whipping in the wind. The signs are fierce and proud, but also hammy and extravagant: the attack, the resistance, the enmity of riot grrrl is still there in Gay Bashers Come and Get It, but tempered with hokey sparkly yarn. The shift from somatic rage to mediated critique is striking, though impossible to attribute, whether to actual change in the treatment of women and queers, to change in strategies for intervention, or to suppression of uncomfortable and countercultural sentiment.

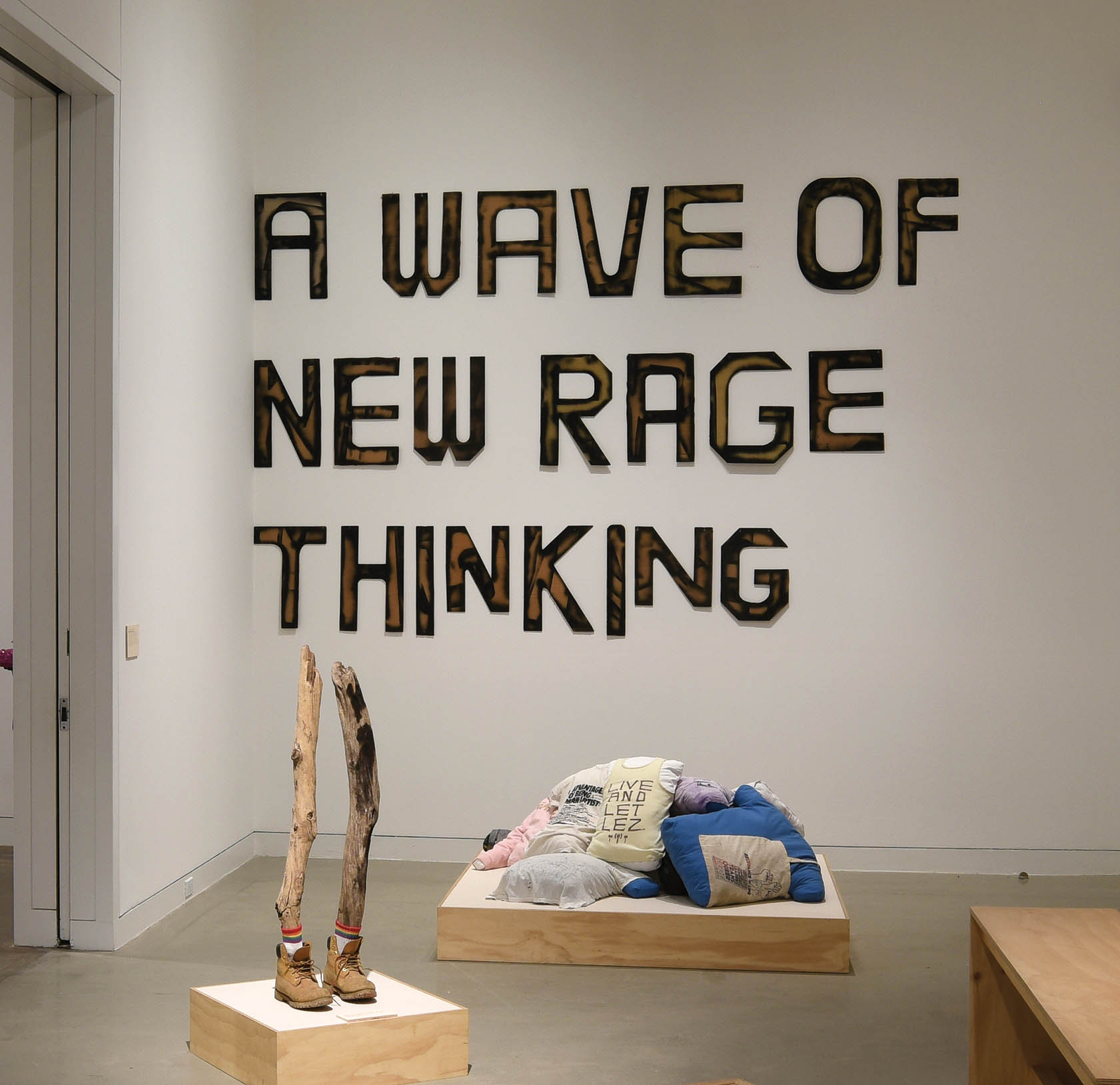

Ginger Brooks Takahashi, installation view, Alien She, Orange County Museum of Art, Newport Beach, CA. Clockwise, from the top: A Wave of New Rage Thinking, 2013, cardboard letters; Feminist Body Pillow, 2013, mixed media, platform: 60 x 60 x 8 inches; and There is a group, if not alliance, walking there too, whether or not they are seen, 2013, driftwood, work boots, socks, platform: 18 x 18 x 8 inches. All works, courtesy of the artist. Photo: Chris Bliss Photography.

Similarly, Ginger Brooks Takahashi explicitly channels the righteous anger of 1990s feminist punk in Feminist Body Pillow (2013), a pile of pillows made from her own and friends’ instructive feminist t-shirts and tote bags. Among them, for example, is a tank top that reads Live and Let Lez (2007) by Takahashi and Ridykeulous’s The Advantages of Being a Lesbian Artist t-shirt (2007), a knockoff of the Guerrilla Girls’ The Advantages of Being a Woman Artist (1989). Essentially a pile of stuffed torsos, the sculpture’s play between cozy and corpselike is destabilizing. Like Roberts’s work, Feminist Body Pillow creates a push-pull between inviting and enraged, a campy and self-conscious form of critique.

It’s easy to forget how profound the early riot grrrl rebellion was, now that we’ve witnessed the commodification of the grrrl punk image during the late nineties. But Faythe Levine’s photographs of radical and off-the-grid communities, Time Outside of Time (2010–ongoing), are a tender reminder that riot grrrl was rooted in the radical urge to create alternative spaces and communication networks to empower women. The photos are simple snapshots with a tinge of fairyland quality. People are dressed anachronistically, homes are self-built, and light filters through green tree canopies. All of this gives the photos a sense of timelessness. The images remind us of the possibility for repudiation of dominant economic and social structures.Levine’s photos also highlight the boundaries of the riot grrrl revolution. In the seventies, some women founded women-only communities; others, regardless of sexuality, rejected relationships with men. Those moves attempted complete rejection of and self-removal from capitalist or patriarchal systems. These new social structures, though, had some of their own social and economic problems, and more importantly, sustenance and longevity proved difficult. If riot grrrl musicians and artists didn’t initially pursue mainstream recognition, they ultimately didn’t shun it either. This ambivalence toward dominant cultures is visible in the work in Alien She. The artists often create alternative spaces and networks alongside or within them, rather than reject them completely. Oft-repeated anecdotes of the punk mosh pit are the perfect allegory for this relationship: Lynn Breedlove tells women at concerts to sit on the stage if they feel uncomfortable, a group of women uses the strength of numbers to push their way to a safe space at the front of the pit, or a woman’s hand reaches out to lift up another girl at risk of trampling by manic boys. These anecdotes suggest that for some, riot grrrls’ goals included visibility, safe spaces, and solidarity within the mainstream.

Faythe Levine, from the series Time Outside of Time, 2010–ongoing. Inkjet print (AP), 22 x 16 3⁄4 inches, framed. Courtesy of the artist.

An example of this productive ambivalence is Stephanie Syjuco’s The Counterfeit Crochet Project (Critique of a Political Economy) (2006–ongoing), in which the artist gives online instructions for crocheting designer purses, and invites participants to send their purses for inclusion in the exhibition. The Counterfeit Crochet Project critiques the circulation of cultural capital through a luxury market, not by tearing down or escaping it, but by building an alternative currency of exchange within it. Parodic videos on the project website show how jealous friends will be of your crocheted Chanel knockoff. If an “authentic” Chanel purse is one kind of status symbol, a crocheted knockoff also comes with its own cool factor in DIY communities. For many people who participate skeptically, ironically, and self-consciously in capitalism, the knockoff is the preferred status symbol. Like couch-surfing, public gardens, and zine exchanges, The Counterfeit Crochet Project creates an alternative—but analogous—system for circulating information, meaning, and cultural capital.

Stephanie Syjuco, The Counterfeit Crochet Project (Critique of a Political Economy), 2006–ongoing. Installation view, Alien She, Orange County Museum of Art, Newport Beach, CA. Gucci Bag (large) by Stephanie Syjuco. Yarn, 14 x 3 1⁄2 x 22 1⁄2 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco. Photo: Chris Bliss Photography.

For me, one of the most beautiful things about Alien She is the way it reveals the intertwined histories of feminist and queer activism and cultural production in the United States. Riot grrrl and queercore music were both born out of the confluence of punk, LGBTQ activism of the era of the AIDS crisis, and feminist histories. Many bands ran in both circles; The Butchies, Sleater-Kinney, and Bikini Kill are among the best known. Similarly, a range of genders and sexualities are represented in Alien She, beginning with Carland’s Lesbian Beds, and ending with the gay/lesbian/queer content of LTTR’s zines. Seeing these histories interwoven feels timely and critical. Recently, queer artists working in Los Angeles have gained institutional visibility, with the Whitney Biennial including Wu Tsang, in 2012, and Zackary Drucker and Rhys Ernst and A.L. Steiner, in 2014, for example, and the Hammer’s Made in L.A. featuring Tsang, Steiner, Harry Dodge, and Jennifer Moon, in 2014. At the same time, trans and queer identities are being negotiated in national media (albeit often conservatively) through figures such as Chaz Bono, Laverne Cox, Caitlyn Jenner, and Jeffrey Tambor’s character Maura Pfefferman in Transparent. Alien She visualizes a history for this moment that is both feminist and queer. The queercore band MEN, which is a direct descendant of riot grrrl (founders Fateman and JD Samson are formerly of Le Tigre) says it best, “For all these years we watched these bodies. Memories of those ungendered dreams.”8

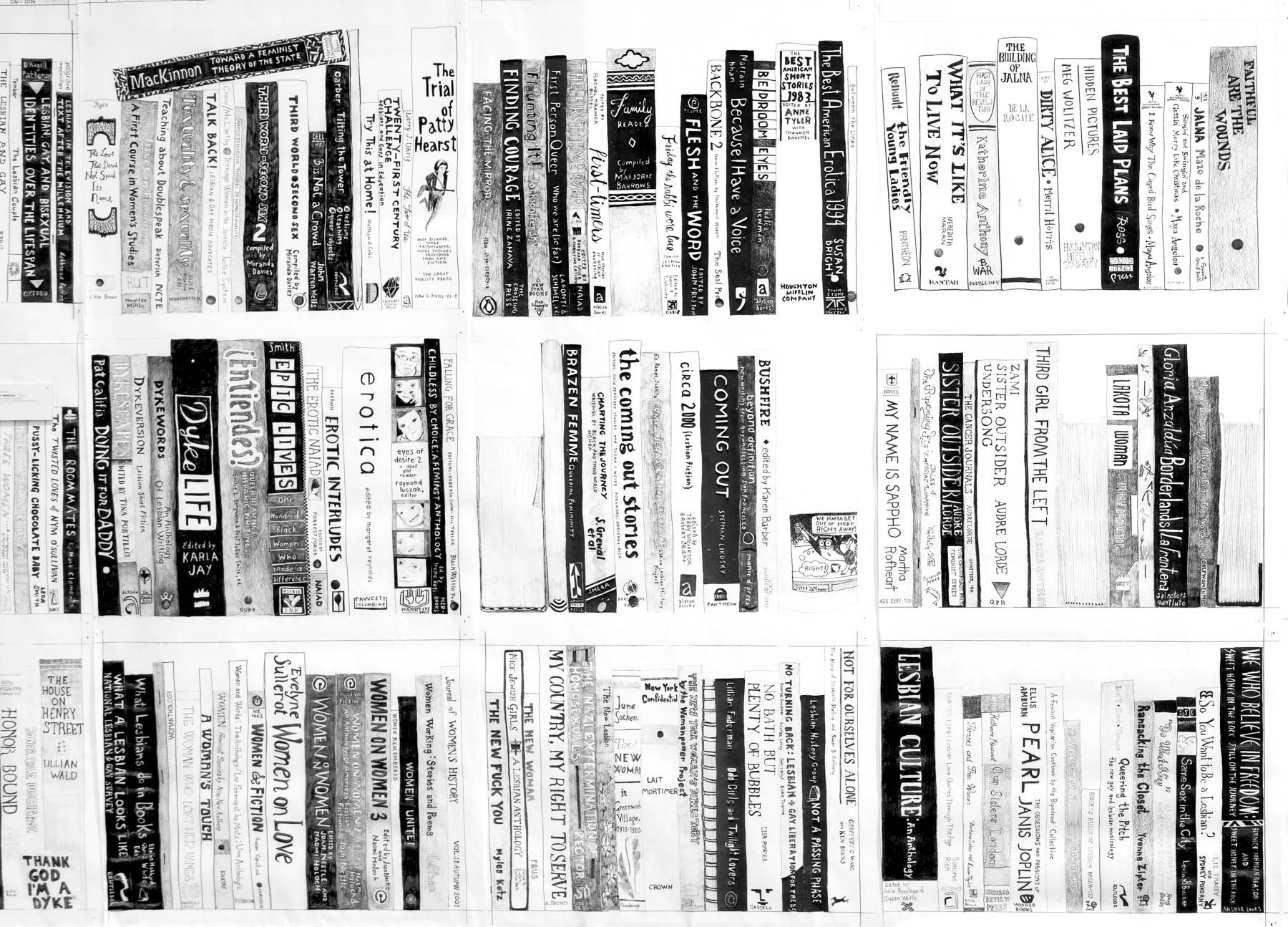

When Alien She presents a portrait of the riot grrrl, she looks altogether queer. Allyson Mitchell’s Recommended Reading (2010) consists of drawings of books on shelves. The drawings are scaled up several hundred percent and repeated across the entire wall, like wallpaper. The titles are sorted alphabetically (loosely), from Abnormal Woman to Youth Liberation and back again. The wallpaper looks like giant Xeroxes—friend of grrrl zines everywhere—of freehand pencil drawings. Canonical classics, by authors such as Radclyffe Hall and Gertrude Stein, are well represented alongside obscure titles, such as Women Without Men, Bi Any Other Name, and a thick stack of the annual series Best of Lesbian Erotica. Titles inform one another, like songs on a mixtape, so that Against Sadomasochism takes on new connotations next to Blood Sisters: Lesbian Vampire Tales. The viewing pleasure parallels snooping through a new friend’s bookshelf. The constellation of titles provides a window into Mitchell’s emotional and intellectual life as a queer feminist intellectual.

Allyson Mitchell, Recommended Reading, 2010. Wallpaper made from photocopied drawings, 388 x 120 inches. Installation view, Alien She, Orange County Museum of Art, Newport Beach, CA. Courtesy of the artist and Katharine Mulherin Gallery, Toronto. Photo: Chris Bliss Photography.

If Mitchell’s labored copies offer a self-portrait via a map of her library, Carland’s Untitled (Lesbian Beds) (2002) series delivers more intimate portraits through domestic objects. Her typology is made up of seven large-format photographs that offer a bird’s-eye view of empty beds lit by morning light slanting across rumpled sheets and pillows. Mismatched pillowcases, decorative details, and last night’s bedtime reading or this morning’s castaway shirt left behind offer hints about the beds’ occupants. Taken together, the women appear to be boho, young at heart, and not settled into traditional domesticity. Several visual puns cue “lesbian”: a pussycat walking across a bed, a pillow popping out of its case with a vaginal effect, and, more explicitly, a Hothead Paisan: Homicidal Lesbian Terrorist pillowcase. In one photograph, a book titled Women in Cuba, a baseball cap that reads Black Workers for Justice, and a lone pillow suggest a woman consumed by her political work. Carland’s project is a counterpoint to Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s Untitled (1991) black-and-white photographic billboards of an empty, tousled bed, with two side-by-side pillows compressed as if two people had been lying there moments before. Made in the heart of the AIDS crisis in the United States and after the loss of his lover, Ross, Gonzalez-Torres’s bed photograph combined the slick language of advertising with the melancholy of absence—a personal yet universal appeal to every passerby: this could be your empty bed, too. In contrast, Carland’s beds are specific, personal, messy, and active. This is her archive of friends, and its political impact is different from Gonzalez-Torres’s billboard. The personal is political in Carland’s work, but in a precise, self-conscious way. There is broad relevance—the pieces open themselves up to personal identification with their subject matter—but no universal claim.

Tammy Rae Carland, Untitled #4 (Lesbian Beds), 2002. Photograph, 40 x 30 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Jessica Silverman Gallery.

In works like Recommended Reading and Untitled (Lesbian Beds), the meaning created is cumulative and partial, building on riot grrrl’s celebration and coalition of many different, individual voices. In this vein, Alien She artist Miranda July uses collective sourcing strategies to create content. Her project Joanie 4 Jackie (1995–2002) is an all girl video chain letter. July passed out pamphlets at music shows throughout the country, asking women to send her their videos and promising to send back a tape with their video plus nine others. Through the project, July wove together a community of women making videos—precisely the one she wanted to be a part of. Joanie 4 Jackie is open and additive; it is representative of this group, but not authoritative. The exhibition also includes July’s better known Learning to love you more (2002–9), in which she and collaborator Harrell Fletcher invited submissions from all over the world in response to “assignments.” For example, “#55. Photograph a significant outfit” elicited photographs with titles such as “what I was wearing when I told him what he did was wrong.” July’s work allows participants to insert their own meanings, lets them be the artist. Both pieces overcome isolation—the isolation of being a woman filmmaker and that of quotidian American life—through an invitation, the fomentation of a movement, and the formation of a community of kindred spirits.

Miranda July and Harrell Fletcher, #55. Photograph a significant outfit: what I was wearing when I told him what he did was wrong. from Learning to Love You More, 2002–9. Exhibition prints from web project and archive; dimensions variable. Website by Yuri Ono. Courtesy of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Moss and Suparak have described a desire to mirror the “crowdsourcing” and networking strategies of riot grrrl in their curatorial strategy.9 The organization of the archives reflects this intention, with ephemera sourced through dozens of friends and colleagues. In addition to zines and flyers, eight regional playlists are available here, including “American South,” “Belgium & the Netherlands,” “Brazil,” “California,” “D.C., Olympia, + Influences.” All are recently compiled by women involved in those scenes during the 1990s. The listening stations, an interactive map of riot grrrl chapters all over the world, and a “Riot Grrrl Census” on tumblr, where anyone can add personal responses to questions such as “What does riot grrrl mean to you?,” evidence the curators’ interest in a collective contribution model.10 In this sense, their curatorial approach is like a mixtape: an idiosyncratic collection that resonates with riot grrrl rather than a methodical delineation of its contours.

Alien She loses some valuable narrative threads in the fragmented curatorial approach—most importantly, the urgency of the riot grrrl revolution. Explicit critique, righteous anger, and vociferous rejection of patriarchy, heteronormativity, and capitalism were primary and powerful in riot grrrl’s lyrics, zines, and performances. The images and texts in Alien She’s archival gallery begin to make this visible, but throughout the rest of the show, the artists appear content to work from within the system to critique it rather than to forcefully repudiate it. Questions about this fundamental tactical shift are left unaddressed in exhibition didactics and, as a result, the force of riot grrrl’s revolutionary stance dissipates over the course of the exhibition. Additionally, the selection of just seven artists to represent the whole of riot grrrl is a weighty curatorial move. The viewer wonders in what ways these practices crystallize the movement. The exhibition never answers this question.

The strategies of the grrrl revolt are particularly important right now, as feminist and queer politics get softened through assimilation. Riot grrrls called for systemic change, but their focus on “the personal is political” and individual rights was seamlessly absorbed by the political and cultural mainstream into (Spice) girl power, punk fashion, and a Lean In brand of self-help feminism. Alien She lacks analysis of this cooptation and the perhaps related shift in interventionist strategies the artists in the exhibition have chosen. A louder curatorial voice, in the form of assessment of the relationship between the historical and contemporary material, and a stronger corralling of the work toward a thesis would have allowed the exhibition to do more heavy lifting around the possibilities and problems within riot grrrl’s political and cultural revolution.

We are hungry for the kind of nuanced history of feminism that Alien She proposes. We need to tease out, elaborate, and assemble the many strands from a monolithic “feminism” now, as we fight new political battles over our bodies and identities. In retrospect, riot grrrl possessed immediacy—an embodied urgency—that feels difficult to recapture amidst assimilation and tolerance. By focusing on recent work, Alien She largely avoids romanticizing punk feminism in the nineties. Instead, the exhibition situates riot grrrl as one touchstone in the multi-stream evolution of the radical personal and political communities that artists continue to build today. Le Tigre’s “Hot Topic,” a literal shout-out to scores of the bands’ political and artistic foremothers, from Nina Simone to Gayatri Spivak, underscores the imperative of these kinds of living feminist histories:

You’re getting old, that’s what they’ll say, but

Don’t give a damn I’m listening anyway

Stop, don’t you stop

I can’t live if you stop11

Claire Ruud is Director of Convergent Programming at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago.