A modern Italian master lived among us but few saw him. Alberto Burri, considered in Italy today as one of the two (with Lucio Fontana) most important postwar Italian artists, came every winter to the dry climate of Los Angeles to relieve his asthma.1 He bought a house in the Hollywood Hills with his American wife and buried himself in work there every winter from 1963 to 1991. The reticent and reclusive artist is remembered today by few people who knew him here.2 Only a single monumental work at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) testifies to his onetime presence in the city.

Recently, the Santa Monica Museum of Art brought back a sampling of the more than sixty major works this notable Los Angeles artist made here in the latter part of his career.3 One objective seems to have been to prompt a re-evaluation of what curator Lisa Melandri calls this “towering figure; the lineage of contemporary art is traced directly back to Burri and to Lucio Fontana. In the canons of American art history, however, Burri remains a shadowy figure, nearly forgotten.” In his catalog essay, Michael Duncan explains that Burri’s “later fall from art-world consciousness is…the outcome of the much-promoted emergence of pop and minimalism and the idea of ‘the triumph of American painting’ and its eclipse of European art.”4 The advent of this show—which occurs just as Los Angeles is preparing a self-congratulatory round of exhibitions and events called “Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945–1980”—may be seen as a warning against nationalist enthusiasms and a reminder to keep our eye on long-range and global art historical perspectives.

In Burri’s case, his reticence, “his disinterest in being his own mouthpiece” to promote his work, may have contributed to its present neglect. His most verbose statement was: “Words are no help to me when I try to speak about my painting. It is an irreducible presence that refuses to be converted into any other form of expression.”5 This restraint seems to have been a part of whatever psychic force drove this artist to produce his compelling work.

Although the work in the exhibition was presented continuously and more or less chronologically, Burri’s oeuvre may be divided between the early pieces and those the artist made after beginning his annual sojourns to Los Angeles in 1963. The early work was confected of distressed materials—burlap rags sewn together, pumice stone collaged with scraps of cloth, strips of burnt veneer or scorched sheet iron, layers of partly melted plastic sheeting—almost all mounted on painted canvas. The Los Angeles work continued the melted plastic series and began two others: monochrome white or black cretti (cracked) canvases that were fissured in shallow relief, and Cellotex panels with geometric patterns in contrasting shades of matte and shiny black.6 The Los Angeles work also included ten black prints produced in textured relief by a special process developed by Mixografia Workshop.

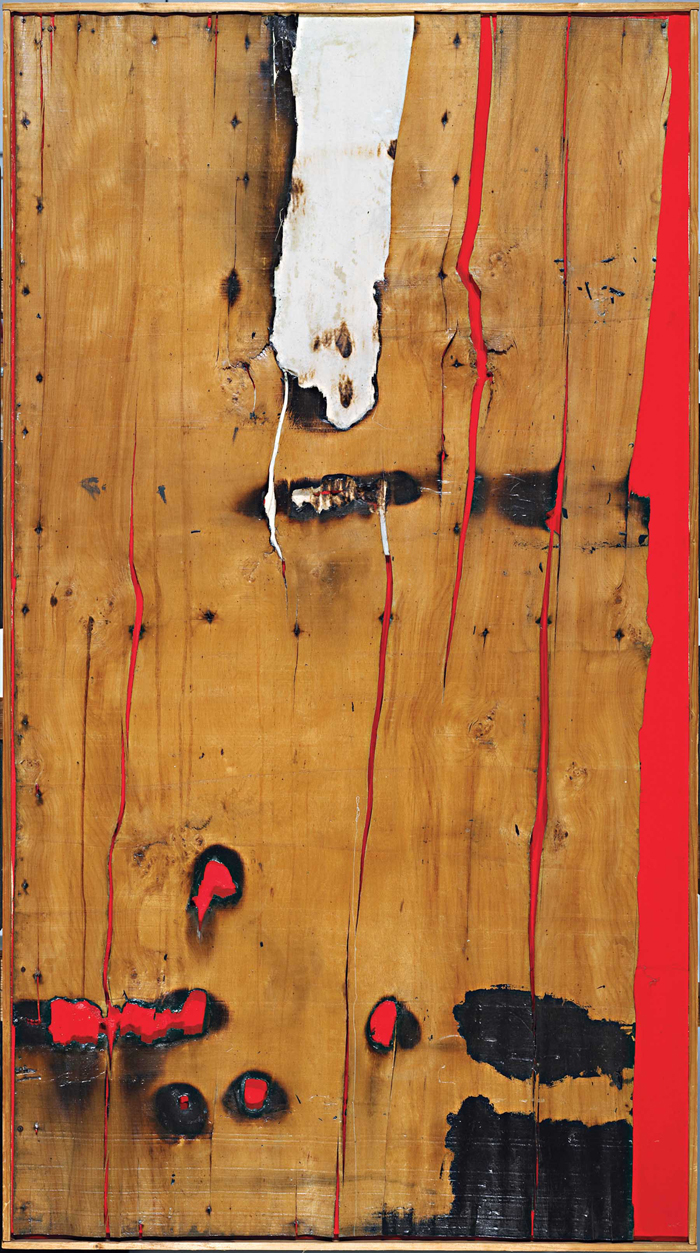

Alberto Burri, Legno e rosso 3, 1956. Painted canvas covered with lacquered bark; 62 1/2 x 34 1/2 in. Harvard Art Museum, Fogg Art Museum, gift of Mr. G David Thompson, in memory of his son G. David Thompson, Jr., Class of 1958. Katya Kallsen © President and Fellows of Harvard College. © 2010 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome.

It may be instructive to compare examples of the early and later work, where a shift in style may also indicate one in the artist’s temperament. Although the sacchi (sacks) are, for reasons that will be explained, Burri’s best known early works, I would like to focus instead on the gorgeous Legno e rosso 3 (1956), which consists of a cracked piece of wood veneer mounted on a vermillion and white canvas almost twice as high as it is wide. Various holes have been charred through the veneer, through which the red shows like a smoldering fire, and it is exposed all along the painting’s right margin. A tongue of exposed white canvas penetrates the upper third, while splotches of black lacquer at lower right complete the balance. In arranging lopsided compositions that upon scrutiny turn out to be classically balanced, Burri has a sensibility akin to Edgar Degas. It is easy to read the veneer screen in terms of the repression that must then have affected this taciturn artist.

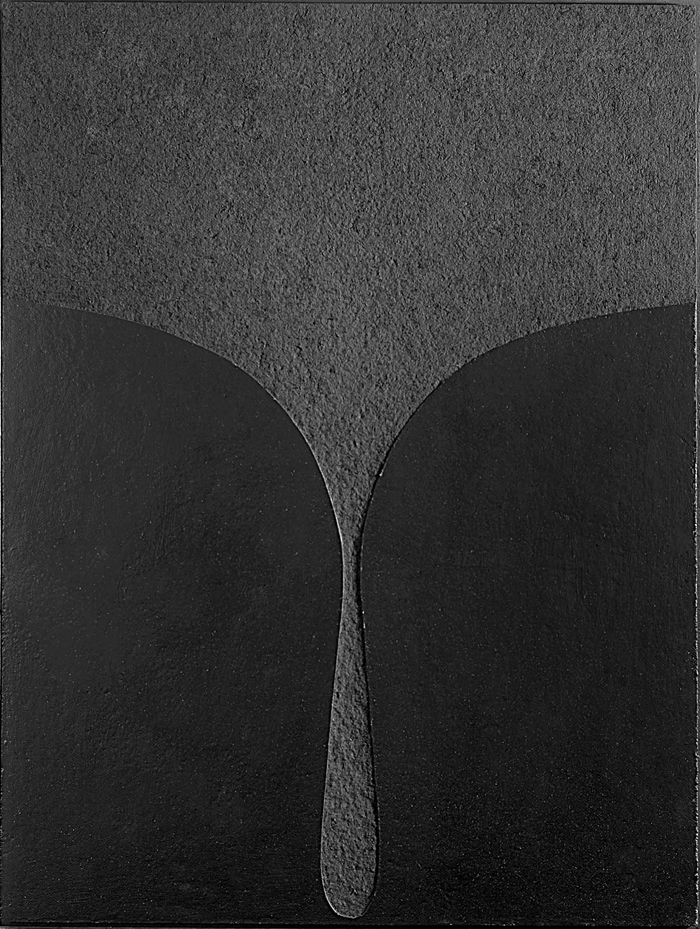

If one turns to the monochrome black Cellotex L.A. 2 (1979), whose title indicates that it was made in this city, the fires of the earlier painting appear to have been extinguished. The lower part of the fiberboard panel has been sealed with Vinavil, so that the acrylic paint retains its shine, while the upper part has been carved out to create a new, more porous matte surface a quarter inch below the original one. The polished boundary between these two black areas sweeps around in a magisterial curve with musical or sexual suggestions. At once ascetic and sensuous, the work is perfectly symmetrical; apparently, balance can now be achieved without struggle. If Degas comes to mind for the earlier work, his more linear predecessors, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres and Jacques-Louis David, might be presiding deities for Cellotex L.A. 2.

Alberto Burri, Cellotex L.A. 2<./em>, 1979. Acrylic and vinavil on fiberboard; 39 3/4 x 30 in. Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini, Collezione Burri, Città di Castello, Italy. © 2010 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome.

At a phenomenological level, the entire exhibition, rather than any one work, seemed to exude a nourishing quality, almost like the remarkable paintings in Marcel Aymé’s short story which, gazed at through a gallery window by a group of homeless men, gradually assuaged their hunger pains and made them feel as though they had eaten a delicious meal.7 I noticed several visitors apparently slowly feeding off Burri’s works as well. Was this only nostalgia for the visceral satisfactions of Modernist painting? An effect of tension produced by the paradoxical nature of the artist’s work?

Perhaps we were partly moved by the pathos of Burri’s life. Critic Enrico Crispolti has insisted that Burri’s work is “autobiographical; in short, the material is soaked in Burri’s private history.”8 Reviewing certain details of that life may help us better understand the work. Burri had been an Italian army doctor in World War II. He was captured in North Africa and imprisoned in a Texas camp for eighteen months; there he first took up painting. Returning to a demoralized and starving Italy, Burri witnessed Marshall Plan aid in the form of wheat in burlap bags sent by those same Americans who had imprisoned him.9 He saw works of art that had been damaged or bombed into rubble, some by American forces. Hence began a series of ambivalences that was to lend Burri’s sacchi work its tension: burlap, patched and ragged, behind which one might glimpse a flash of scarlet paint. This former doctor seemed to be binding up the wounds of war. In America, the work was read as signaling humility, and the word “redemption” appeared in critical responses. The paintings were shown several times in prestigious venues such as the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh.10

In this early period, Burri also took up a blowtorch and began to singe wood veneers, to heat up sheet iron until it turned iridescent, to melt exquisite holes and crannies into layers of transparent plastic sheets. The exhibition’s title, “Combustione,” derives from this use of a blowtorch. The subdued violence of these processes excited critics, including Germano Celant, who explained that one shaped canvas

almost seems to rise, seething, a terrestrial crust beneath which sleeps a root fighting to emerge into the light.… [T]he material he dealt with was in torment. Reflecting on itself, it presented its wounds and its dramas, lifted up great walls of color and fabric, offered itself up, overflowing, flaunting the beauty of the abandoned.… Burri’s materials had to suffer: wood and metal were assaulted by fire, they passed through the inferno.…11

Combustione: Alberto Burri and America, installation view, Santa Monica Museum of Art, September 11–December 19, 2010. Photo by Jessica Chermayeff. Works, from the left: Grande Ferro M-4 (1959), Grande Nero Cretto L.A. (1978), and Grande Bianco Plastica (1962).

In the mid-1960s, shortly after he began to winter in Los Angeles, U.S. art world interest began to turn toward American artists and away from Burri and other Europeans. Burri changed, too. Critic Maurizio Calvesi’s opinion in 1971 was that “During the sixties his anger dissolved, and with it his aggressiveness.”12 Critic Giuliano Serafini sees a major crisis developing at this point in the artist’s career: “[T]he artist now realized that his linguistic and instrumental repertoire could no longer progress gradually in a straight line. In order not to exhaust it, he had to make a radical change in direction.”13 This change led to the cretti and the paintings on Cellotex. Melandri associates the latter with rapid building expansion in Los Angeles during the 1970s, and the former with Burri’s visits to the parched landscape of Death Valley.14 The cretti were worked flat with a mixture of kaolin, resins, pigment and polyvinyl acetate, which cracked as it dried. By diluting this mixture, the artist controlled the size of cracks and areas between them, and he could arrest the process by applying Vinavil glue; unique in Burri’s work, chance was allowed to intervene.15 “In the black cretto it is the surface which overrides the fissures; in the white, it is the sign of the fissures themselves that define the surface.”16

At some point in the 1970s, Burri’s presence in Los Angeles came to the attention of Vasa Mihich, a sculptor teaching at UCLA. Mihich mentioned him to Gerald Nordland, director of the UCLA Wight Gallery.17 Nordland knew Burri by reputation and invited him to do a solo exhibition and a large project on campus, which turned out to be a wall sixteen and a half feet high and almost fifty feet long in the university’s sculpture garden. The wall, which is apparently the only work by Burri that remains in Los Angeles today, is composed entirely of ceramic tiles expanded from pieces in the model cretto shown in the Santa Monica exhibition. In 1977, Burri had an exhibition at the Wight Gallery that included sixty-two works, five of which reappeared in the Santa Monica show and another three of which closely resembled pieces exhibited there.18 Although half as large as the UCLA show, the Santa Monica exhibition both partly restaged the Wight exhibition and presented post-1977 work from the final stage of the artist’s career. The latter exhibition also revealed what the former hadn’t specified–that Burri had been living in Los Angeles all along. One might say that “Combustione” was both a reprise and a completion of the Wight project.

The design of the Santa Monica show, which guided the viewer in a single, zigzag path between facing walls, implied a certain inevitability between the earlier work and the later. This impression of a unified corpus of work was further heightened by a preponderance, with a few exceptions, of canvases with black, brown, and white tonalities, which seemed to lead into the later monochromes. Burri himself, in a rare statement, supported this impression by saying, “My last painting is the same as my first.”19 This was the show’s “argument” and it was a plausible one. But one should also be aware that inclusion of other artworks, such as Burri’s wildly colored tempera paintings or the acrylics of the Sestante cycle (1983), would have shown a different picture of the artist. Likewise, Burri’s theater designs and actual sets—some of which he did for performances by his wife, Minsa Craig, a dancer and choreographer, at the Pilot Theater in Los Angeles—might have shown to what extent this solitary artist was capable of collaborating with a partner.20 Serafini contested a straight-line, chronological progression of Burri’s work, and it is further questioned by the ambivalences that characterized Burri’s life.21

Alberto Burri, Sacco L.A., 1953. Burlap and acrylic on canvas, 39 5/16 x 33 7/8 in. Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini, Collezione Burri, Città di Castello, Italy. © 2010 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome.

“Los Angeles is nothing,” Burri said, “not even a city.” Why then did he remain here so persistently? Only for his health? To visit the desert? To support his wife’s dance activities and spend time with her family? Serafini speculates: “For more than twenty years, the [Hollywood Hills] were a sort of no-man’s land which protected him in some way from the world.”22 Further, Burri “did not have a positive impression of the American art world,” especially after it began to neglect him. He pointed out that he had used the American flag in his work before Jasper Johns and thought (and some critics agree) that Robert Rauschenberg’s combine sculptures had come out of the American’s 1953 visit to Burri’s Rome studio, where his sacchi were on display.23

A different kind of ambivalence emerged in the artist’s sequestration of his work. In 1978, Burri returned to his hometown, Città di Castello, near Perugia, and with local authorities set up a foundation to collect and install his work in a refurbished palace. The artist bought back what he considered to be his best work and donated major new works to his foundation, which opened to the public in 1981. Ten years later, the burgeoning work had outgrown its housing and a second building, a former tobacco drying house, was acquired by the foundation. Burri also supervised compilation of a catalogue raisonné with almost two thousand of his own works, which the foundation published in 1990. The foundation galleries, which the artist installed and forbade to be modified, along with the catalog, are the artist’s works no less than his paintings and sculptures. Taking so many paintings off the market meant that pieces remaining in private hands became very valuable, so collectors became hesitant to lend. After Burri died in 1995, a legal struggle over ownership of the work broke out between the foundation and Minsa Craig (and her heirs). This struggle, which lasted eleven years, must have caused collectors to become even more skittish. By sequestering his work in the foundation and at the same time ambiguously deeding it to his wife, Burri restricted the selection available to the Santa Monica Museum of Art.

Of the twenty-five major works in the Santa Monica exhibition (not counting the ten prints), twelve—including almost all the works made in Los Angeles—were lent by the foundation. Given the acrimony of the legal struggle, this may have led to downplaying Minsa Craig’s role in promoting Burri’s work within the exhibition catalog.24

One of the paradoxes around Burri’s work is that although it appears focused on materials and the processes that transformed them, those processes have been arrested and the work preserved in its natural wood frames like a fly in amber. Much of the work has then been further preserved within the frame of the foundation’s galleries. “The painter’s main concern was to see his complete oeuvre kept together, alone, far from contamination,” says the foundation’s former director, Nemo Sarteanesi.25

Alberto Burri, Bianco Plastica L.A. 4, 1965. Plastic, acrylic, vinavil, and combustion on fiberboard; 29 3/4 x 25 1/2 in. Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini, Collezione Burri, Città di Castello, Italy. © 2010 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome.

“Burri’s humility is the measure of his extraordinary greatness,” the critic Pierre Restany once said, referring to the artist’s aristocratic refusal of self-promotion.26 That may be so, but the obverse of this humility was the obsessive pride and distrust implied in the artist’s attempt to cocoon and seal off a corpus of work from the world. According to Calvesi, that work displays:

a disdainful secession seemingly motivated by personal reaction to a political situation and by a latent, bitter love of homeland.…[J]ust as time in life converges on the immobile dimension of death, so the action of Burri—the act of slashing, of wounding the material, of stitching it up or burning it—ultimatelyleads to inactivity and inertia. The “Sacks” become tombstones…Burri’s action becomes fixed, sealed into stasis, a state that can be equated with death.27

Alberto Burri, Cretto L.A., 1976. Acrylic and glue on fiberboard; 12 13/16 x 10 in. Collection of Isabella del Frate Rayburn. © 2010 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome.

How then to explain the feeling of nourishment experienced in the galleries of the Santa Monica Museum of Art? Writing recently, Celant attributes such qualities to the fact that “Burri continued to believe in the central role and psychic qualities of things and materials, which he saw as a character, a mirror of human life.”28 Calvesi saw in Burri’s work a manifestation of “Art as ransom and redemption, as the embodiment of ethical values, as revolt against or escape from a frustrating human condition.”29 To this I would add, for the earlier works, a spirit of defiance, and one of acceptance and reconciliation for the later ones.

Melandri cites Calvesi to the effect that Italy “virtually dismissed Burri” until after he had made his reputation in America in the mid to late 1950s; by 1959, the positions were reversed.30 The work made in Los Angeles has now all been sold at elevated prices in London and Milan. The Burri story, as told in Santa Monica, is one of an artist who, despite a certain rigidity, purveyed his own ambivalence to fruitfully negotiate the space between two art worlds. Although he kept his distance, he was our adopted son, and the recent visit here of his work renewed this city’s traditions of looking beyond its own shores to welcome artists from abroad.

Michel Oren has published in Art Papers, Art Journal, Sculpture, Cleveland Studies in the History of Art, Cultural Studies, Performing Arts Journal, History of Photography, Exposure, Third Text, Callaloo, Aztlan, Studies in Black American Literature, and Contemporary Literature. He is a visiting researcher in the Visual Arts Department at California State University, Fullerton.