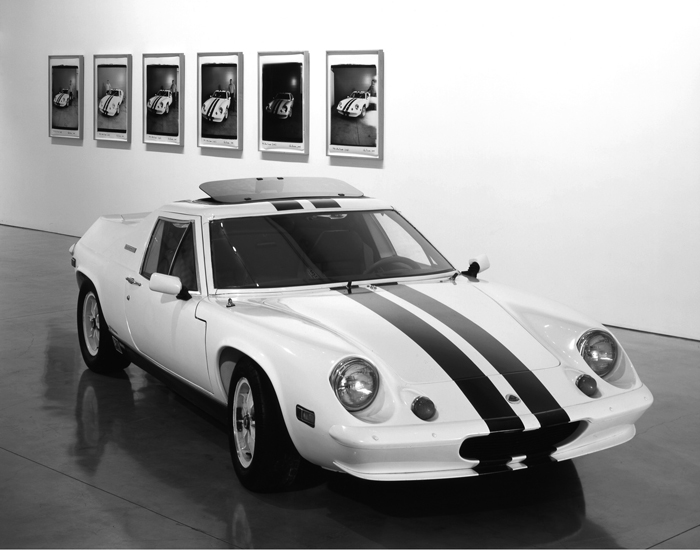

Chris Burden, Lotus, 2006. Approx. 1,500-pound 1973 Lotus Europa and set of 6 original color polaroid photographs. Lotus: 42 x 152 x 64 inches; Each photograph: 24 x 20 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery. Photo © Douglas M. Parker Studio.

My first trip to Los Angeles took a total of 36 hours. It was only supposed to take 24, but the train my friend and I had boarded in Seattle met with some “unexpected delays.” We had decided to take the train for a few reasons: it was cheaper than flying, we could bring more stuff (which was important because we were moving everything we owned), and we dreamed of a leisurely ride down the West coast, peering over bluffs at the ocean from the comfort of our Amtrak recliners. As it happened, the misleadingly named Coast Starlight Express only went along the coast for about 200 miles. There was neither coast nor starlight, and the only thing “express” were the microwaved hotdogs and burnt coffee. Most of the trip was through the flat California interior, with its mix of spinach farms, orchards, and heavy industry. The small section of coast we were able to see was a few hours north of Los Angeles near San Luis Obispo. Transfixed by the open water, I nearly missed the intercontinental nuclear ballistic missile silos scattered among the hills as we passed through Vandenberg Air Force Base. When the train stopped just outside the base my friend and I ate vegan sandwiches at a café that specialized in lunch hour crystal therapy healing and “energy realignment.” Being spiritually cleansed in the shadow of Mutually Assured Destruction seemed a little perverse to me, but no one else seemed to mind.

This uniquely Southern Californian coexistence permeates Chris Burden’s recent show at Gagosian Gallery in Beverly Hills. Titled Yin Yang, the exhibition is made up of two vehicles and two corresponding sets of large format Polaroid photographs. The vehicles are a Lotus roadster from 1973 and an International-Harvester T6 tractor from the mid-1950s. Underneath the vehicles in the gallery were small swatches of felt, presumably used to soak up any stray grease or oil that might drip onto the pristine floors. There was also a noticeable lack of tread marks, indicating the vehicles either levitated into place or a great deal of care had been taken to make it appear that way. The photographs show Burden standing politely, almost meekly, next to the vehicles in what looks to be a garage (although, with the penchant for cement floors in most contemporary exhibition spaces, it could easily be another gallery). The combination of the actual cars and the portraits fits somewhere between an example of an obsessed collector and a high market art world version of a hip-hop album insert, with the Bentley’s and bling being replaced by more peculiar but equally useless status symbols.

A cursory read of the exhibition would lead one to believe that Burden was interested in presenting a simple binary, two related objects with radically different uses. The blunt presentation and cheesy title make it easy to overlook the implications of pairing intricate and heavy machinery with Taoist/Neo-Confusian philosophy. Southern Californians are used to the gross misuse of Eastern philosophy for the purposes of self-help and spiritual cleansing. The truly postmodern mish-mash of spiritual movements in Southern California, from Buddhist hybrids to Scientology to the old-school occult, is a well-documented phenomenon and predates the 1960s and 1970s.

Burden’s title reveals itself to be self-referential, not simply a title but another component of the piece on equal footing with the objects. The vehicles are two permutations of the same thing, covering two poles of possible use: the purely functional tractor and the elaborately non-functional sports car. The yin to the vehicles’ yang is the influential presence of new age philosophy in Southern California. These philosophical movements coexist with the petroleum and aerospace industries, forming a seemingly contradictory set of subcultures that in fact feed off one another, both financially and ideologically. A prime example of this scientific/spiritualist cohabitation was Jack Parsons, one of the founders of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Parsons was an avid occultist and would often pray to Pan before the launch of test rockets.1 Burden’s Yin Yang points to this little-explored relationship between science and esoteric spirituality in a coy manner by taking advantage of common Los Angeles obsessions with cars and enlightenment, making the presentation immediately familiar and pedestrian.

Chris Burden, Bulldozer, 2007. Approx. 5,000-pound 1954 international T6 crawler and set of 4 original color polaroid photographs. T6 crawler: 65 x 112 x 54 inches; Each photograph: 24 x 20 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery. Photo © Douglas M. Parker Studio.

This is not to say that Burden’s work is critical of or explores these relationships in any generative or even documentary manner. The exhibition is an example and a symptom of this flow, not a self-aware project that adds to our understanding of the unique cultural circumstances of this particular time and place. Nor is it an attempt to change our relationship to the objects and ideas present in the work. While Burden’s work can be seen as negotiating between real and symbolic power, so can the work of native Californian think tanks like the RAND Corporation. Many of the strategies pioneered by RAND in the decades after World War II bolstered an emerging synthesis between military know-how and academic abstraction and speculation. But this newly strengthened relationship between the military and academia didn’t stop at war games and notions of “force projection.” In 1968, RAND published papers on bureaucracy in Vietnam, UFOs and parapsychology, and total nuclear war. Also in that year, two RAND engineers filed patents for a new invention: windsurfing.2

After I got off that train from the Pacific Northwest three years ago (still picking pieces of sprouts and portobello from between my teeth), I vowed to be more generous in my reading of art—to eschew some of the jaded crust that had accumulated after four years of undergraduate art education. I would visit galleries and remind myself that “these people care about what they’re making just as I care about what I make, we’re all in this together…” Seeing beyond the simplistic (not to be confused with simple, which can be elegant and profound) binary of Yin Yang and overlooking the bland display of ego in Burden’s show was a difficult read that took a great deal of effort on my part. It was hard to reconcile what I know about the artist historically and the work I was confronted with at Gagosian last summer. Many of Burden’s early works challenged both the abstract and real power of art and culture, making use of actual physical trauma to explore the role of the individual in the context of an increasingly alienating mechanical world. Yin Yang ultimately dragged the viewer down with its passivity and resignation. Perhaps Burden was always complicit with the power structures he set himself against. His recent work denies the ability of art to inhabit and transform culture from within and rejects its capacity to change our relationship to experience and knowledge. Perversity abounds in Southern California, fueled by contradiction, cohabitations, and a continuous flow of individuals and industries. There is potential in this perversity, but it relies on active participants not passive representatives. As Thomas Pynchon once said, “Each will have his personal Rocket.”

Brendan Threadgill is an artist and writer living in Los Angeles. His works have been seen recently at LAXART in Culver City and at GLAMFA in Long Beach, not far from the oil drilling platforms disguised as tropical-palm-studded islands. Threadgill is also a former Fulbright Fellow to Ukraine, where he explored the depths of post-Soviet ennui from the window of his Kyiv apartment.