The passing of Chris Burden last year brought to a close one of the most significant artistic careers in American art of the last half-century. Burden’s great theme was the precariousness of individual existence in the post-industrial age, and he pursued it across a field of limit-seeking undertakings that, to a previous generation, would have seemed implausible, if not impossible. Burden boldly opened and closed entire genres, sometimes within the course of a single work. His critique of the norms and ideals of art institutions is ultimately more trenchant than that of Marcel Duchamp, his early model. His use of extremely large (and extremely small) scale rivals the most logistically ambitious engineered sculptural undertakings of recent times. His disquieting explorations of masculine-gendered modes of play are as cutting as that of any self-identified feminist artist. No American artist in recent memory has toyed with the machinery of art world celebrity more revealingly, or more adroitly. In its restlessness and relentlessness, and in its combination of critical acuity and sculptural wit, his work explores the relationship between power and knowledge with a depth that is only beginning to be understood.1

Art writers typically work against the grain of their subjects. When faced with an apparently stylistically uniform body of work, they usually attempt to elucidate the qualities that are unique to particular works. When faced with a wildly heterogeneous body of work, they often task themselves with describing the hidden thread that all of the works supposedly have in common. Burden’s practice poses massive challenges for these habits of writing, due to its temporal span, its boggling breadth of subject and technique, and its wide lateral leaps. Ideas fluoresce in one work and sometimes quickly disappear, only to be revisited in highly revised forms many years, or decades, later. In an earlier phase of interpretation, it seemed sufficient to subsume Burden’s early well-known performances into the broader categories of the later sculpture. Burden’s own statements have tended to reinforce such a view.

Stills of Chris Burden from L.A. Artists, 1978, by Richard Newton. Super 8 with magnetic sound, color, 16 minutes. © Richard Newton 1978, 2015. Courtesy Richard Newton.

The monumental catalog of Burden’s work, which was published by Locus+ in 2007, decisively undermined this viewpoint. Organized by theme and not by chronology, the book’s structure seemed to be intended to elucidate commonalities between works across his entire career. But in the case of Burden, this classic art historical device is most fruitful to the very extent that it backfires. To browse the catalog is to enter an art historical maze of rotating walls, trapdoors, false exits, and trick mirrors. The gap between an act or object and its media representation varies widely and precipitously, inducing a kind of representational vertigo. The most extreme anti-metaphoric positions themselves become metaphors, only to be resituated in new contexts, situations, and objects in which the presumptive conceptual structure of the earlier work is undermined or called into question. The book’s effort to consolidate Burden’s work into categories revealed as never before the work’s unruliness, its intense self-contradictions, its interdisciplinarity, and its calculated refusal of traditional subject categories. In most artists’ work, the earlier work teaches one how to look at the later work. In Burden’s case, there are many such cumulative effects of enrichment, but because nearly every piece explores and occupies a new promontory from which to view the oeuvre as a whole, simple correspondences between early and late fail to capture the complexity of the work. The old charge of incoherence, routinely leveled at Burden throughout the 1980s and 1990s, is clearly obsolete, but a full view of the work and its manifold receptions has yet to be produced. This short essay suggests an approach to the subject by sketching the artist’s endpoints: his first and last works.

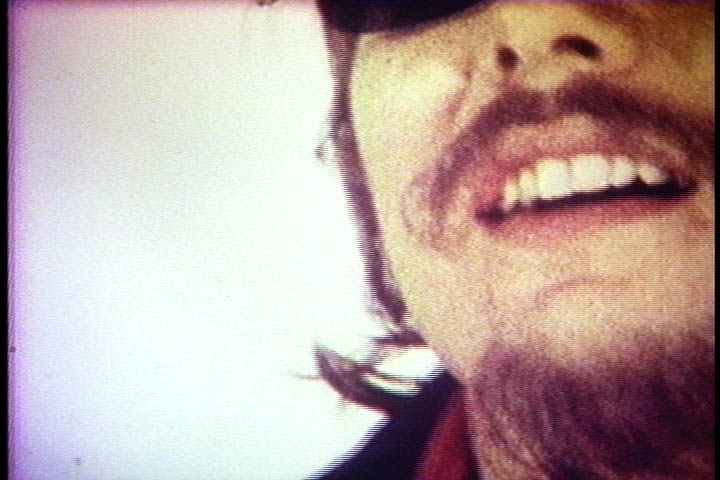

Chris Burden, Being Photographed Looking Out Looking In, 1971/2006. © Chris Burden. Courtesy Chris Burden Studio and Gagosian Gallery.

First Moves

A largely unexamined point of departure is Burden’s first documented performance, Being Photographed Looking Out Looking In (1971).2 Staged at F Space in Santa Ana, the piece had three elements. The first consisted of a gallery attendant who photographed visitors individually with a Polaroid instant camera as they arrived. The second element was a wooden platform suspended from the ceiling by chain link. An A-frame ladder offered visitors a path to the platform. Reclining on the platform, visitors could look up through a rubber eyepiece and see the sky. The third element involved a bathroom in the corner of the space. In the bathroom door, Burden installed another one-way eyepiece, with a distorting fish-eye lens, and sat on the lid of the toilet in the bathroom for the duration of the performance. Visitors could see him through the eyepiece, but he could not see them.

Being Photographed states the artist-viewer-world triad familiar from philosophical aesthetics in unusually bald terms. Each of the elements summarizes, in condensed form, a popular notion of what art viewership is about, with an acute attention to the audience’s experience of presence, of presentness. The Polaroid portraits at the entrance gratify an audience’s desire to literally see itself in the work. Here is the second-hand Kantian notion of aesthetic pleasure as self-enjoyment, deliberately tipped into a social space in which it could easily be read as narcissistic self-regard. The ascent of the ladder, a minor climb, pays off with a unique view of the cosmos, the world outside. It is an ordinary view of the sky, one that could be seen anywhere, but it is socially activated by being framed and presented by the artist. (In a drawing made much later, in 2006, the artist describes the experience of looking through the scope as akin to flight: “[Viewers] see nothing but sky and fast moving clouds. The sensation is floating, high speed travel through the sky.”) Finally, the blurry distorted view of the artist alone in the bathroom, sitting and thinking, without any apparent awareness that he is being observed, offers a glimpse into the artist’s “private” world. The chance to see the artist literally sitting on the pot is both a fulfillment and a spoof of Romantic notions of art providing access to the artist’s brooding, dreamy introversion.3 Being Photographed doesn’t exactly affirm one of these three modes of viewership so much as impassively lay them out for the viewer to navigate. In retrospect, it’s clear that in this piece Burden was laying out the threads that he was preparing to intertwine.

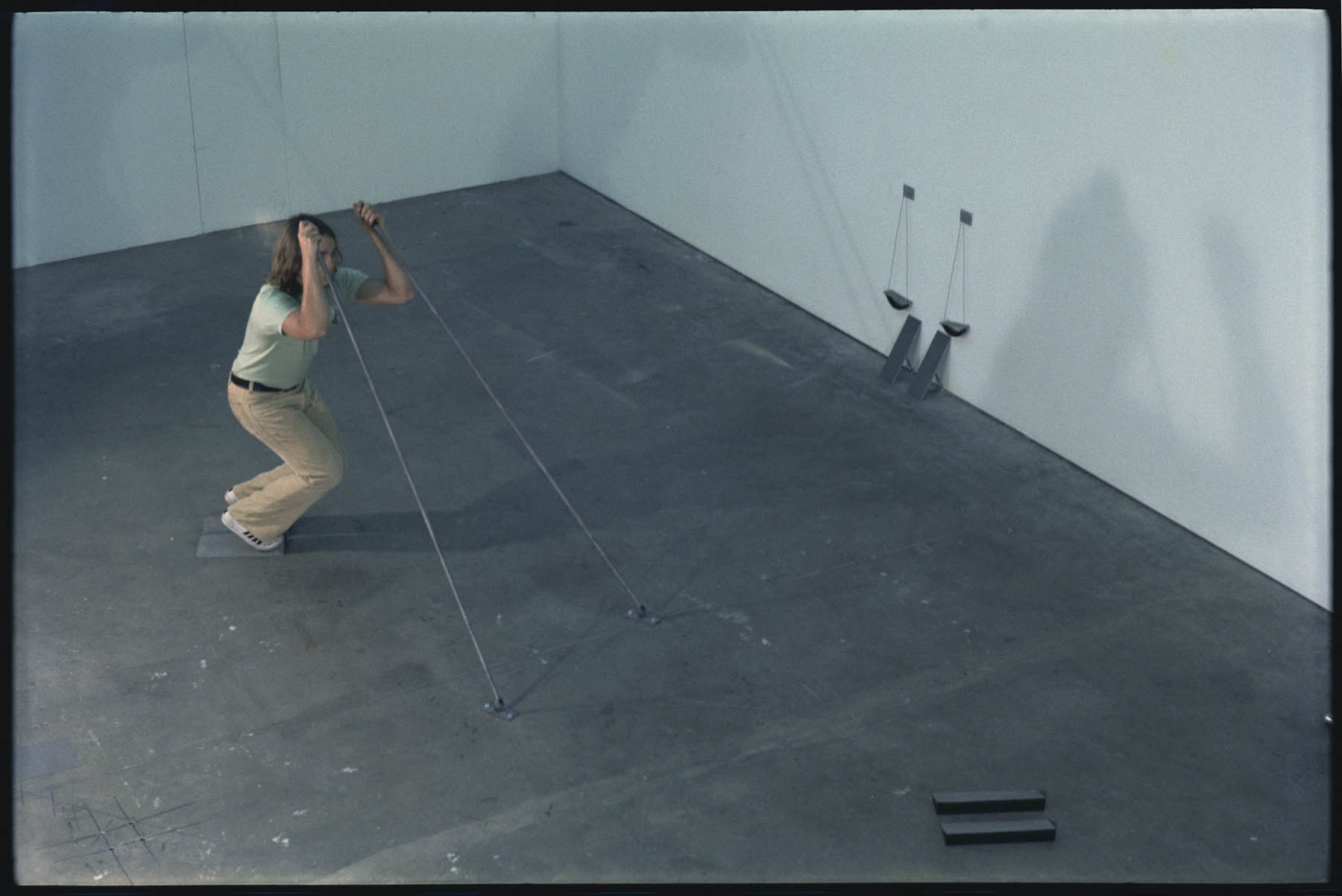

His previous works, produced as an undergraduate at Pomona College, weren’t performances but rather interactive environmental sculptures that demanded an active viewer. One consisted of a pair of arched steel pipes, their footings set in cement. The pipes were set in an open field, 100 feet apart, with a translucent plastic canopy stretched between them, forming a tunnel. Because one arch was eight feet tall, and the other was two feet tall, the corridor formed between them was progressively constricting. The viewer could easily walk in on the taller side, but would be forced to kneel, then crawl, if he wanted to emerge through the arch at the opposite end. A group of other metal works consisted of T-bars, rods, and stirrups that, when stepped into, required the viewer to locate a difficult-to-maintain balancing point, either alone or in conjunction with the counterweight of another visitor. These works are fundamentally about gravity and the body’s experience of negotiating and sustaining a resistance to it. Defying the physical force of gravity would turn out to be one of Burden’s great themes, one that connects the ordinary daily experience of the body to the world of sculpture, architecture, and engineering. He would return to the subject often, in gravity-defying works that emphasized the subjects’ military, technological, and aeronautical histories.4

Chris Burden, untitled, 1969. © Chris Burden. Courtesy Chris Burden Studio and Gagosian Gallery.

In this very early phase, Burden’s work has obvious affinities to post-conceptual art of the 1960s, particularly that of Bruce Nauman. Also a product of the California MFA system, Nauman was five years Burden’s senior. Both had fathers who were engineers. Both began in a post-minimalist mode, highly informed by the resurgence of interest in Duchamp in the 1960s. Nauman’s various early performances involving falling and gravity relate closely to Burden’s early “balancing act” metal sculptures. Nauman’s sound recording Get Out of My Mind, Get Out of This Room (1968) is an obvious precedent for Burden’s Shout Piece (1971), a performance in which he repeatedly yelled at the audience to get out of the room. Nauman’s Performance Corridor (1969), which subjects the visitor to a very narrow walk space, is contemporaneous with Burden’s constricting corridor of plastic of 1969. Each of these works uses strategies of physical disruption to heighten the viewer’s bodily awareness of the immediate environment and to create a mood of physical menace.

Chris Burden, The Fist of Light, 1993. Aluminum, HVAC equipment, halide lights, 96 x 96 x 120 inches. © Chris Burden. Courtesy Chris Burden Studio and Gagosian Gallery.

This list of comparisons could be extended. Nauman’s Sealed Room— no access (1970) offers up the spectacle of a large room, with no entrances or exits, emitting only the whirring sounds of several large industrial fans. It bears obvious comparison to Burden’s much later The Fist of Light (1993), also a sealed room. But this comparison mainly serves to illuminate their differences. The Fist of Light, the viewer is told, has its internal walls covered with a grid of high-energy lightbulbs. The walls thus exist to protect the viewer (by containing the blinding radiant energy generated) as much as to exclude him from the mysteries within. Where Nauman’s piece emits a low hum, Burden’s emits the roar of the five-ton air conditioning unit needed to cool the room. Burden’s piece and his oeuvre in general are louder and hotter.5

Burden’s initial breakthrough involved the insertion of his own body into the narrative of the work. This solved multiple problems. First, it allowed him to relax the demand for direct audience participation. Viewers wouldn’t have to step into any stirrups if they didn’t want to; they could watch him model the behavior in question and imagine it for themselves. Paradoxically, by allowing the viewer to remain passive during a performance (a mode many viewers greatly prefer), their passivity itself could become an object of contemplation and critique. For example, one question raised by Five Day Locker Piece (1971) was the extent to which the viewer was morally required to summon help, break the padlock, and free the artist. Of course, no one did this, but the question of the audience’s obligations saturates the work. Second, using his own body allowed Burden to escalate the physical severity of his performances to a level to which one could not ethically submit the public itself. The extreme hijinks that followed opened a radical counterpoint to the impersonality of minimalist ethics, raising psychological questions of machismo, masochism, and subjection. Third, by using existing structures and materials, like the school locker in Five Day Locker Piece, he could fully dispel the misreading of his constructions as abstract sculptures to be appreciated for their formal qualities. The problem of sculpture as such wasn’t highlighted so much as bracketed.

Chris Burden, Apparatus Sculpture, 1969–70. © Chris Burden. Courtesy Chris Burden Studio and Gagosian Gallery.

One ironic corollary of Burden’s move to the first-person performative mode is that it ultimately served to locate his performance pieces in memory, in a foretime. Given their poetic emphasis on an ephemeral presentness, they could only slip into the past. As such, they are lore, not repertory. He never expressed interest in re-performing them, and when artists asked permission to re-perform them, he refused that permission. This turn would be decisive. Where Nauman’s preferred mode of address is an imperative, sometimes instructional mode, where first, second, and third person are indifferently permuted in the present tense (“I have work. You have work. We have work. This is work.”6), Burden speaks consistently across his entire career in a first person past tense: I did. This strategy was in many ways gratifyingly conventional. It allowed the reader/viewer to locate the artist seemingly definitively within the work, like the vision of the artist glimpsed through the eyepiece in the bathroom door.

Burden seems to have realized instantly that his performances would achieve significance mainly as media objects.7 Burden’s preferred form is a single memorable graphic image, usually black and white, with a location, date, and terse, memorable first-person description. The precise layout is unimportant. The form is essentially that of the image/text pairings of a modern catalogue raisonné. Later descriptions of his sculpture (typically photographed in color) would take much the same form, though often admitting of a bit more art historical context. Burden’s media objects concretized, with unparalleled pith and wit, the endgame of the dematerialization of the art object: art could simply become an anecdote. For many audiences, the wilder and the more harrowing, the better.

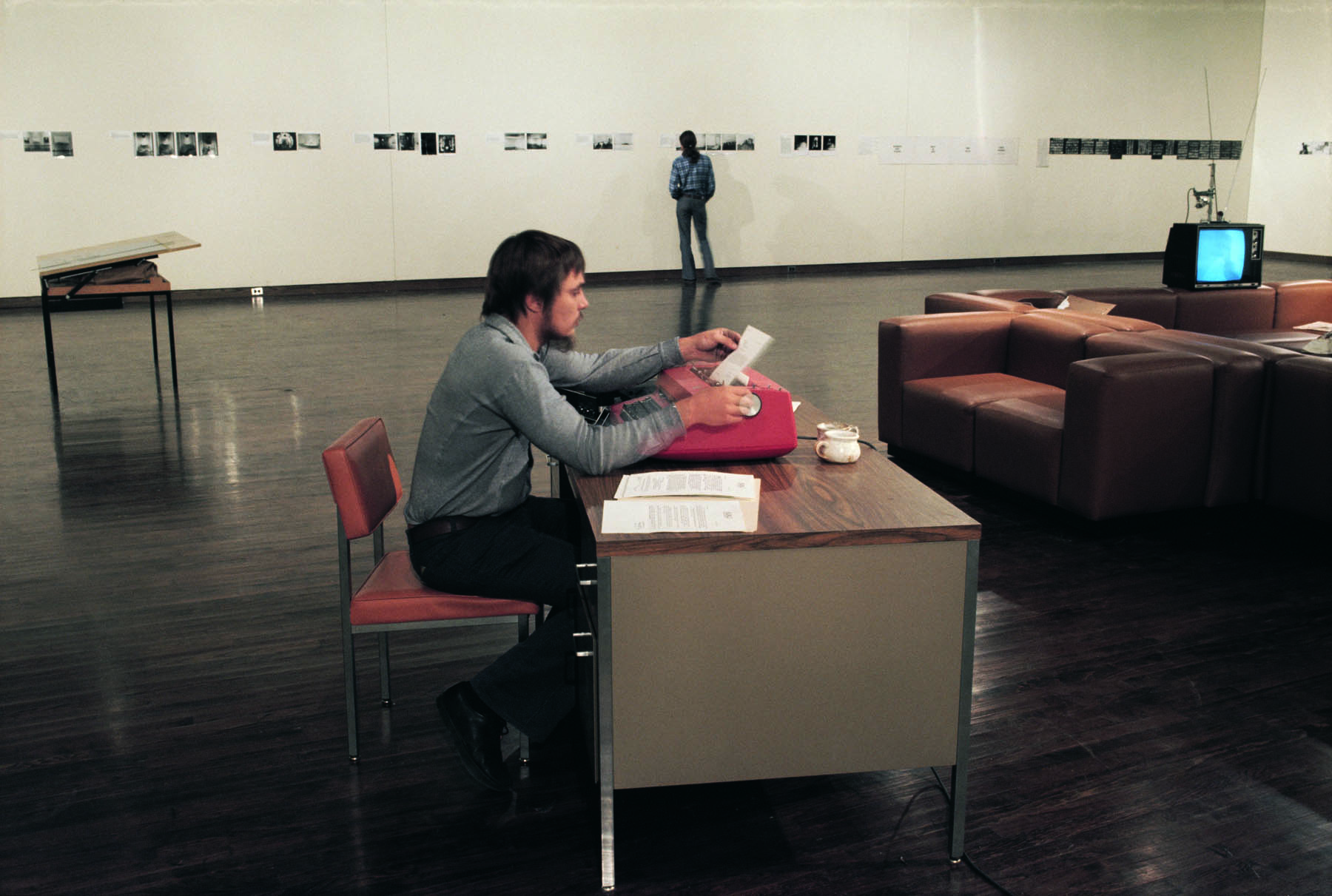

Chris Burden, Working Artist, 1975. © Chris Burden. Courtesy Chris Burden Studio and Gagosian Gallery.

These media objects offer a cool counterpoint to the intensely visceral nature of the events that they depict, a contrast inherent in reportage forms that is, in a sense, the true object of the work’s study. In the performance Working Artist (1975), made at the time of Burden’s crucial initial pivot to sculpture, he set up an office in the galleries at the University of Maryland. He hung photographs and written explanations of his performances on the walls, and conducted his daily business in the middle of the room: typing letters, making phone calls, and watching TV. Visitors were confronted by the difference between the disturbing events depicted in the photos and the banal real-time business of running an art studio. Burden’s juxtaposition of youthful stunts gone dangerously far and an adult aesthetics of administration raised blunt questions about the interrelationship of these modes. Do they conflict, or are they in fact interdependent? Was the artist pulling off the mask of his persona, or pulling it down even tighter? Are we “looking in” or “looking out”? Even with the benefit of hindsight, it’s hard to answer these questions precisely, which is partly a measure of the work’s strong heuristic value.

The question of the performances’ veracity was inevitably raised. I once watched an interviewer demand to see the scars on Burden’s hands from Trans-fixed (1974), the performance in which he was briefly crucified to the back of a Volkswagen Beetle. Burden demurred. “I used tiny nails. No scars,” he shrugged. Because so many of the early performances were performed in private, or for small audiences, Burden connoisseurs have mixed opinions about which of the works really happened. For example, did he truly stay in that locker for five days straight? The UC Irvine poster says 8:00 a.m. to 10:00 p.m., and Barbara Burden, the artist’s first wife, has said off the record that he got out at night to snack and stretch. Perhaps the round-the-clock version of events is a later embellishment.

No matter, these performances were made to be recounted, and the press predictably obliged. The article titles give some sense of the ideational flow: Newsweek in 1973: “Death for Art’s Sake.” Penthouse in 1975: “Is Violence Art?” The Know in 1975: “Chris Burden: Self-Torture Is Art.” Playgirl in 1978: “Chris Burden: Picasso used Canvas, Michelangelo used Marble, Chris Burden Uses His Body.” These articles cemented the idea, repeated endlessly ever since, that Burden’s performances were testing the limits of the body, in perhaps the same way that Greenbergian modernism tested the limits of painting. There is clearly something to this idea, but it needs to be heavily qualified. Burden’s performances were not “investigations” yielding significant data about the limits of the body, a topic far more directly addressed in kinesiology, or even professional sports. Nor did they set any new world records. Somewhere in India, I feel certain, is a swami who has spent years inside a metal box. Nor was anyone ever seriously injured in a Chris Burden performance. Burden’s most significant early “sculpture” was immaterial: an intensely persuasive (and largely fictional) persona. The crucial aspect of these works was their integration of the techniques of persona construction (for example, paid public television ads that Burden made later on) into the very interior of the work. The medium of Shoot (1971) is rumor, not rifle/bullet/arm. The artist’s last name, with its connotation of a heavy load to be carried, was the perfect brand for an aesthetics of existential terrorism and self-jeopardy, which was thrown into high relief by the post-minimalist art styles of reduced affect that were predominant in the early 1970s.

The strongest criticisms of Burden have been directed at the alleged juvenile character of the materials used in some of the sculptures. Vito Acconci, his old rival, wrote in Artforum last year: “I can’t stick with him when he’s inside a world of miniatures and children and toys.”8 A fuller articulation of this viewpoint comes from Howard Singerman, one of Burden’s most perceptive critics. Singerman’s 1981 essay “The Artist as Adolescent” links Burden’s art to that of Mike Kelley. In Singerman’s view, “[Burden’s] goals are not to humanize technology or mystify its potential but to mimic it. Like the adolescent with a crystal radio set, Burden absorbs facts and parades knowledge.”9 For Singerman, Burden’s deliberate failure to explicitly provide the criticism of technology that his mostly liberal audience expects, while provocative, ultimately displays an amoral lack of ideology, which marks his work as postmodern. Singerman distinguishes critically between the childlike and the childish, arguing that modernism celebrated the childlike as a glorious return to a state of innocence, but disdained the childish as a failure to be fully socialized.

Drawing from Luella Cole’s The Psychology of Adolescence, Singerman characterizes adolescence partly as a transition from a desire for facts to a desire for explanation. Indifference to explanation is the mark of a failed transition to the adult state. Going further, he adds:

The adolescent [Burden] recalls is stridently male as are the roles his props offer—the pilot, the general and, in The Big Job, the trucker. They are the sexually segregated and societally condoned role enforcers of postwar America. In exchange for the values they enforce, they offer the adolescent not only speed—adolescent transcendence—but the dual succors of risk and adventure on the one hand and belonging and regimentation on the other.10

The immediate target of Singerman’s essay is The Citadel (1978), a Burden sculpture/performance involving a darkened room with an installation of hundreds of tiny metal toy ships. During each performance, the artist manipulated a light around the room, creating some cheap theatrical effects, and played a crackly soundtrack that was a pastiche of science fiction references. On the spectrum of silly to serious that Burden’s sculptural work occupies, The Citadel is on the far end of silly.

Singerman’s criticisms are perceptive, and partly accurate. Burden’s art speaks entirely of male role models, often intensely macho, an aspect of the work that post-feminist criticism has called attention to.11 But this isn’t a fault per se, rather simply a feature. Singerman doesn’t consider the possibility that Burden’s work enacts an ironic critique of masculine American hubris.

Chris Burden, The Speed of Light Machine, 1983. © Chris Burden. Photograph by James Dee. Courtesy Chris Burden Studio and Gagosian Gallery.

One senses that Singerman’s real difficulty with the work concerns its unhinging of knowledge and power. Burden’s displays of scientific knowledge shorn of any conception of political power, and his shows of violent rhetorical power deprived of any specific political logic or sense, are rightly troubling to a generation of critics who have, following Foucault, come to think of knowledge/power as a single, composite concept. For example, The Speed of Light Machine (1983), Burden’s reproduction of a nineteenth-century experimental apparatus for measuring the speed of light, relocated into a museum of art, does not by itself reveal much about the society that produced this innovation in quantification. Scale Model of the Solar System (1983), which shows the sun as a 13-inch sphere, and the planets proportionally reduced, is an exercise in scale that is highly familiar from high school science lesson plans. The knowledge it encodes is presented as a bare fact, devoid of its political ramifications. Burden’s parroting of antique scientific devices in an art context (as opposed to that of a museum of science and industry, where some of his pieces would conventionally be more at home) at worst betrays some sort of silly self-satisfaction at the fatuous notion of having in some sense “discovered it himself.”

Another difficulty with Singerman’s critique is that the boundary between the childlike and the childish is in practice often difficult to locate. The socialized desire of an adult to share information and a child’s desire to “parade knowledge” are closely related, in development and in memory. Separating the good aspects of a generalized childhood sensibility from the bad turns out to be difficult, in the sense that innocence is another word for ignorance. As gaming theory and research has shown, toys and games are tools of socialization that form identities and express ideological views of the world, but they are also psychological coping mechanisms that allow individuals both young and old to experience a feeling of power. Burden’s play with “children’s” toys is superficially a transgression of an American taboo, in the obvious sense that men are supposed to play with motorcycles and cars, and not paper airplanes and toy ships. But Burden played with all of the aforementioned and much more in his work, which in one sense gestures less at childhood specifically than at a utopian, expanded sense of play that doesn’t respect boundaries of age.12 However, the fact remains that the toolbox of some of the late work is socially classified as kids’ stuff, a reality that was not lost on the audience or the artist. His modeling of a regression to a state of childhood play in certain works is a social reminder that the world as experienced by children (large, opaque, and often scary) remains largely the world that we live in as adults. In a society in which limit-seeking behavior is coded as adolescent, it was perfectly logical for Burden, a limit-seeker par excellence, to have sought to explore the origins and basis of that encoding in popular notions of childhood play.

Chris Burden, A Tale of Two Cities, 1981. Installation view, Chris Burden: Extreme Measures, October 2, 2013–January 12, 2014, New Museum, New York. © Chris Burden. Courtesy Chris Burden Studio and Gagosian Gallery.

Old Futures

The last work Burden completed in his lifetime is Ode to Santos Dumont (2015), a sculptural model of the petroleum-powered dirigible that the pioneering Brazilian aviator Alberto Santos-Dumont built and flew single-handedly around the Eiffel Tower in 1901. The first presentation of the work occurred at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art over a month-long program in the summer of 2015. The technical centerpiece is a working quarter-scale gasoline engine, expertly machined and hand-assembled by the inventor John Biggs, to whom the piece is dedicated. The sculpture is “performed” by an attendant (at LACMA, Biggs himself) who activates the sculpture by removing some anchoring weights, topping up the helium in the balloon if necessary, slowly guiding the dirigible through the space, and then firing up the gas engine that spins the propeller at the tail end. Once released, the airship, tethered by wires to the ceiling and floor, flies in a slow circle around the room, until the fuel allotted for the voyage is spent, and the piece begins a slow, gradual descent, until the attendant returns it to a platform. The whole process takes about twenty minutes. Biggs fondly recalled to me the first successful test flight of the assembled device, in an airplane hangar. After ten years of planning and testing, at the model’s first moment of free flight, Burden, at that point seriously ill, began leaping up and down, waving his hands, and “squealing.” While not every viewer may feel quite that exuberant, the piece is, by museum art standards, gob-stoppingly fun.

In his home country of Brazil, Santos-Dumont is a revered national hero, with many streets, a town, and an airport named for him. A small, quiet, and impeccably stylish man who was the heir to a coffee fortune, he designed and built an extraordinary series of one-person flying machines in fin de siècle Paris, at a time when flying was both unregulated and spectacularly dangerous.13 He was a hobbyist-inventor who sought and realized an experience of profound personal freedom, floating high above Paris alone in his airship, in which brunch was customarily followed by glasses of champagne and Chartreuse. His flights were always recreational, and almost always unaccompanied. He never sought any patents, shared all of his work openly, and donated all of the money from the many prizes he won to charity and his assistants. Like many inventors of his era, he was convinced that his work would be a force for world peace. A genuine folk hero to the people of Paris, who bought gingerbread cookies in the shape of his profile and played with toy versions of his dirigibles, he would eventually be eclipsed in history books by the Wright brothers, whose pioneering test flights had taken place slightly earlier in the United States, though in secret. (In Brazil, the question of historical priority is still hotly debated.) Santos-Dumont would die by his own hand in 1932, during an aerial bombing campaign of the Brazilian civil war, profoundly grief-stricken by how his invention had become a tool for death-dealing.

Chris Burden, Ode to Santos Dumont, 2015. Installation view at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, May 18–June 21, 2015. © Chris Burden. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA.

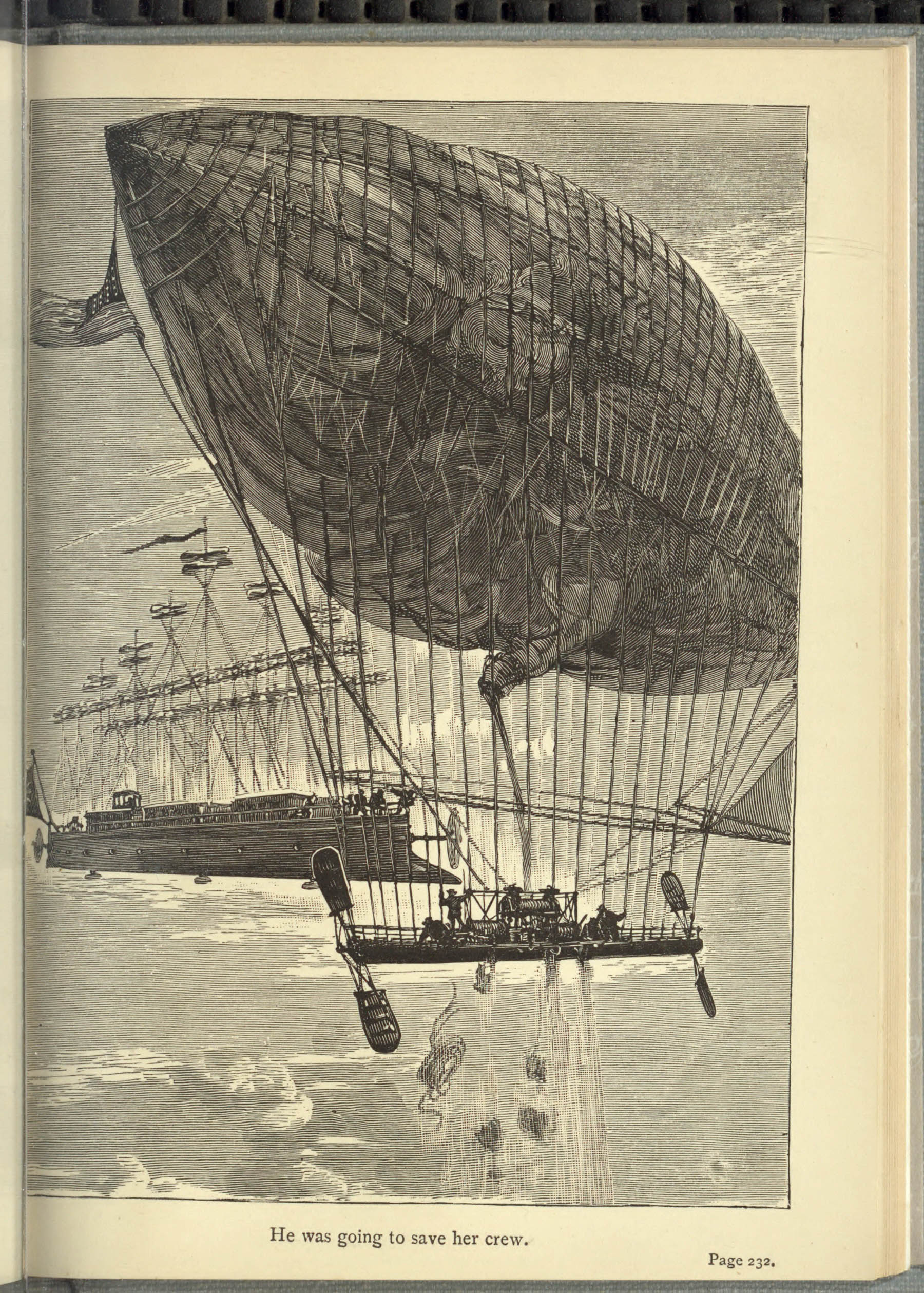

Ode to Santos Dumont invokes the fiercely romantic legend of the man himself, but gestures more broadly at the hopes and anxieties attending the golden age of mechanical engineering that flourished in Europe (and Paris especially) at the end of the nineteenth century. The literature of Jules Verne is the essential text here. Verne’s novels of voyages extraordinaires, with their characteristic mix of geography, exploration, and adventure, provided an ideational blueprint for an entire generation of engineers and industrial designers.14 At the dawn of mainstream science fiction in the Victorian period, life appeared to imitate art, partly because Verne was careful to write mostly about inventions that he fully believed to be feasible. The developmental link between childhood fantasy and adult undertaking, one of the crucial themes in Burden’s psychology of power, is unusually explicit across the literature of this period.

Woodcut illustration by Léon Benett in Robur the Conqueror, by Jules Verne, published in 1886. (Published in London in 1887 as The Clipper of the Clouds.) Benett produced nearly 2,000 illustrations for Verne. Their process was collaborative, and the images can be taken to closely represent the specificities of Verne’s vision. See Arthur B. Evans, “The Illustrators of Jules Verne’s Voyages Extraordinaires,” Science Fiction Studies XXV: 2 (July 1998), 241–70. Online at http://jv.gilead.org.il/evans/illustr/.

Verne, one of the earliest members of the Societe d’aviation, believed fervently in the future of heavier-than-air flight. For decades, the society’s magazine Aeronaute drew correspondence from inventors all over the world keen to contribute to the new age of flight. These theories would find their literary expression in Robur the Conqueror (1886), Verne’s manifesto-like adventure novel, which dramatizes the conflict between lighter-than-air and heavier-than-air approaches to aviation. In the novel, Robur is an antihero genius who pilots the Albatross, a frigate-like airship held aloft by multiple helicopter-like propellers. He kidnaps the members of a balloon enthusiast’s club and takes them on a high-speed trip around the world. The story ends with a spectacular air battle, which Robur’s ship wins decisively, but Robur refuses to reveal the ship’s secrets. A sequel, Master of the World (1904), produced after Santos-Dumont’s celebrated 1901 flight, is even more dystopic in tone. In it, Robur has created an even more powerful machine, the Terror, which can navigate on land, air, or sea. Master of the World is characterized by a pervasive mood of foreboding that is implicitly linked to a fear of totalitarianism. Balloons and dirigibles like those of Santos-Dumont were, for Verne, a gentleman’s novelty that was destined to be swept aside by a more powerful regime whose ultimate results could not be controlled.

Ode to Santos Dumont approaches this complex history in a characteristically ambiguous fashion. While Santos-Dumont always insisted on an exuberant yellow Japanese silk for his balloons (not registered in the era’s black-and-white photography), Burden skins his model dirigible in a neutral, colorless semi-transparent plastic. Both creators’ sense of delight in the processes of tinkering is unmistakable. The overall mood of Burden’s work is affirmative; there is no sense that Santos-Dumont is being subjected to any sort of personal critique. On the other hand, the tethers that guide the flight create a palpable sense of constraint.15 Watching the work in action can feel a bit like watching a trained pet being taken for a walk. This isn’t free flight; Ode is a drone. Burden’s lighter-than-air sculpture is literally leashed by institutional forces larger than it. Like the massive restraining bolts visibly drilled in the underside of Michael Heizer’s “levitated” boulder outside, Ode’s attachment points partly define the work as a specific encounter with the limits of institutional (and insurance industry) tolerance, which has its own peculiar politics and poetics of risk-aversion. The literal vision of “floating, high speed travel through the sky” that Burden ascribed to his very first performance is only remotely symbolized here, and the historical gap implicit in that symbolism has a delicate undercurrent of both tragedy and nostalgia.

Chris Burden, 25 Foot Stepped Skyscraper, 2014. Stainless steel reproduction Mysto type 1 Erector set parts on stainless steel base; 300 1 39 1 391⁄2 inches. Installation view, Chris Burden: Master Builder, February 14–June 8, 2014, The Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University. © Chris Burden. Courtesy Chris Burden Studio and Gagosian Gallery.

Antique futurology is a major theme of Burden’s late work. The sculpture Medusa’s Head (1990) is, among other things, a caricatural vision of how fin de siècle artists and writers imagined life in a hundred years: a sooty, de-spoiled sphere of ugly industrial debris, a heinous, unlivable, environmental catastrophe. It hasn’t quite turned out that way. Or has it? Also in this vein, Metropolis II (2011), on view indefinitely at LACMA, is a kinetic model of a city whose architecture is a dense accretion of late nineteenth and twentieth-century utopian building styles ringed by freeways whose cars never stop. The work is a profoundly disquieting depiction of the modern urban rat race. In the world of Metropolis II, old futures don’t get demolished, they just get hemmed in by later ones, their sightlines blocked by later developments. The question implicitly posed is whether or not such an ecology can be made livable. Burden lived through an age of mainstream apocalyptic prophecies that never materialized, like the “Y2K bug,” predicted to destroy computer systems at the turn of the millennium, a prediction for which he had a great morbid curiosity. His work’s relationship to technological fatalism is complex, perhaps partly because his personal relationship to the subject was itself so complex. In its willful lack of ideology, Ode to Santos-Dumont arguably childishly reduces the political question of air power to the technical question of aeronautic knowledge, separating Santos-Dumont’s germinal airship from both the science/fiction culture that spawned it and the monstrous industrial apparatus that would immediately harness it. Yet in its nostalgic evocation of an aeronautical world before warplanes, an unspoiled Eden of the skies, it is also optimistic, playful, and childlike in the best modernist sense.

Benjamin Lord is an artist based in Los Angeles.