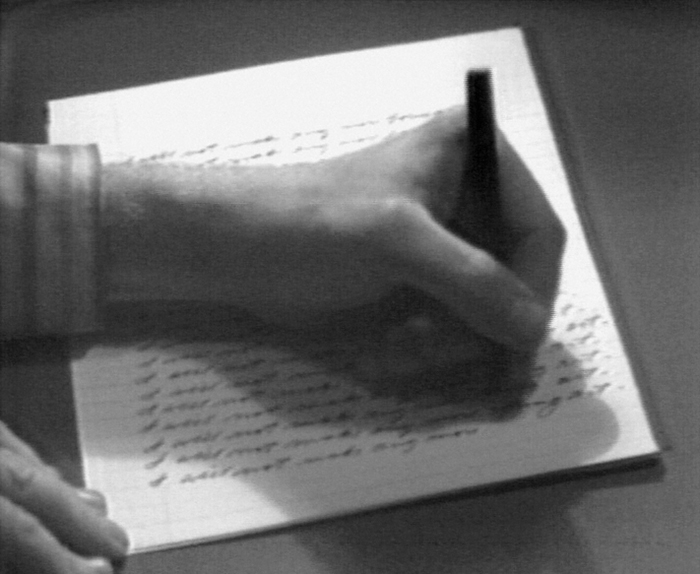

A blank legal pad fills the screen of John Baldessari’s I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art (1971), the very first piece in California Video, the Getty’s survey of forty years of video art in the golden state. The artist’s hand fills the paper with the titular phrase in the rote manner of a grade-school penalty. Although the tape tops out at near thirty minutes, the endless playback loop might cause one to imagine Baldessari trapped in a recursive closed circuit of punishment and promise, for he reneges on his pledge at the very moment of its making. But even with artist’s tongue firmly planted in cheek, I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art does not succeed at being boring: not only does its absurd humor increase with each ironic repetition, it also offers an implicit critique of its parent medium. Baldessari undermines the conven- tional pleasures of television by creating a self- consciously boring program. Curator glenn Phillips juxtaposes I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art with a pair of Diana Thater’s works, Surface Effect (1997) and Continuous Only (2006). If Baldessari’s piece introduces the visitor to early video art’s humorous challenges to the medium, Thater’s work points to themes more endemic to contemporary work. Surface Effect’s two channels appear on monitors stacked base-to-base, bottom image mirroring the top. Each screen shows the big sky of a psychedelic sunset over a low mountain range. But as the clouds slowly shift, it becomes apparent that the spectacular colors are not from nature’s palette, but from the television itself. The vibrating hues are purely the effect of the scrolling electronic surface of the screen. The technology is front and center, dazzling when it calls attention to itself. Continuous Only achieves the opposite effect. Its nine flat-panel screens show a fragmented yet synchronized view of dense tropical foliage, as if one is looking at the ground through a perforated screen. The erratic movement of the camera causes the viewer to automatically fill in the gaps between the monitors, making the image whole and comprehensible. In this unconscious act of erasing negative space, one also erases the technology—the expensive screens roped together by big loose loops of cable disappear and become transparent.

Paired together, Thater’s and Baldessari’s works map both what is seductive and dangerous about video art. on the one hand, it often seems to run the risk of investing too heavily in the wizardry of effects and fetishizing the technology. Or, conversely, it makes the physical, technological, and institutional supports of the object disappear in favor of a fantasy of unmediated connection to the image on the screen. If it does manage to avoid the traps of fetishism and transparency, it may not hold its audience long enough to get the joke, since, if one is conditioned to expect anything from television it is the relentless forward motion of entertainment. Thater’s and Baldessari’s works, along with many others in California Video, engage in a struggle with television: though seduced by its formal potentials, its pervasiveness, and its powers, at the same time they are desperate to overturn its oligarchy, pluralize its producers, and undermine the very pleasures it delivers.

Phillips stages an engrossing exhibition of some of the greatest—and some of the least recognized—pioneers of the medium. The show compels many returns to the gallery, not only due to the sheer volume of the work (to even estimate the collective running time of all the tapes is dizzying), but also for the conceptual heft of the works it contains and the continued relevance of the critiques of the medium and the media that they offer.

The heavy front-loading of California Video reflects the Getty’s burgeoning interest in the medium’s early years. fifty-one of the exhibition’s seventy-three works date from before 1988, and nearly forty of those are from video’s first decade. Twenty or so of the videos on display are from the museum’s video collection. The collection—one of the largest in the world—includes the Long Beach Museum of Art’s unparalleled archive of early California video, which the Getty acquired in 2005. Beginning in 1974, the Long Beach Museum was an early supporter of the new medium; the institution collected and archived tapes and established editing and broadcast facilities for artists. The LBMA’s deteriorating tapes from video’s salad days now share a home with the Getty’s far more ancient treasures. while the mass-reproducible cassettes make strange bedfellows for the rarefied, singular works that make up the bulk of the Getty’s holdings, they are equally delicate and in as dire need of attention from both conservators and scholars.

Rosalind Krauss diagnoses these early years of video in her seminal polemic, “video: The Aesthetics of Narcissism,” published in 1976 in the inaugural issue of October. She writes: “In the last fifteen years [the art] world has been deeply and disastrously affected by its relation to mass-media. That an artist’s work be published, reproduced and disseminated through the media has become, for the generation that has matured in the course of the last decade, virtually the only means of verifying its existence as art.”1 Krauss offers a general condemnation of video art as fundamentally narcissistic—video artists are not interested in addressing their audiences, but in seeing themselves on screen. Vito Acconci’s Centers (1971) epitomizes the character of all video art for Krauss. for a long twenty-two minutes, Acconci points to the center of the screen, at the viewer. But in the moment of making the video, Krauss observes, Acconci is not pointing at the spectator but at his own image on the monitor.“…what we see is a sustained tautology: a line of sight that begins at Acconci’s plane of vision and ends at the eyes of his projected double. In that image of self regard is configured a narcissism so endemic to works of video I find myself wanting to generalize it as the condition of the entire genre.”2

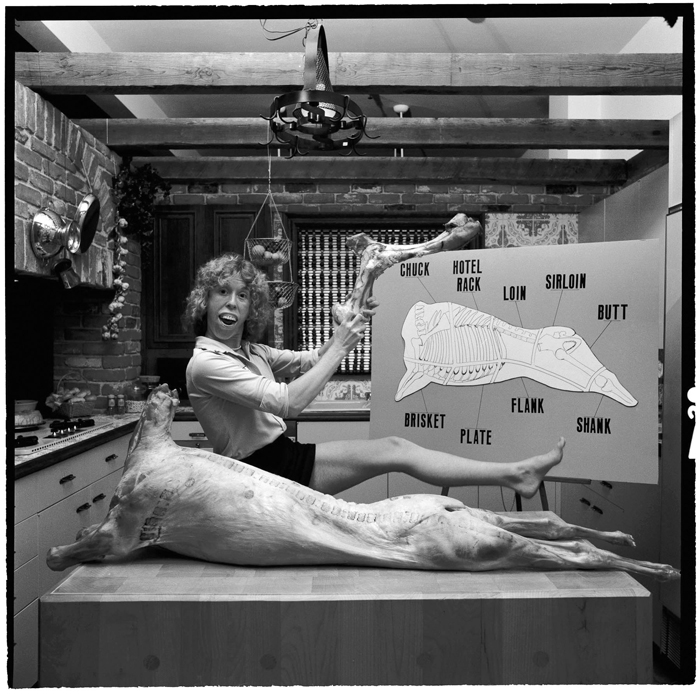

Instead of being doomed to an endless narcissistic entrancement with video feedback, the artists Phillips has carefully selected for the Getty exhibition avoid this critical fate. The artists’ own bodies do still occupy many of the screens in California Video, but their interest isn’t primarily in using the monitor as a mirror. Instead, they take up the television screen as the most relevant public space, suggesting that its codes, conventions, and content are elements of culture in urgent need of critique. Rather than accepting an art world in collusion with mass media, as Krauss saw it, many of the artists in this exhibition aimed to disrupt the smooth functioning of broadcast television; occasionally, they succeeded.3 Phillips unearths from the archive works that often don’t make it into the canon of early video, giving deserved recognition to artists who were working outside conventional art world spaces, artists who were more concerned with the boob tube than the white cube. while this counter narrative to Krauss’s story is not a specifically Californian one, the early works in the show easily find their place in the mythology of California in the vietnam era. free love, radical politics, psychedelic aesthetics, and collective action are writ large across the exhibition. with the New Yorkers missing, there is a marked absence of formal, “narcissistic,” closed-circuit experiments; Bruce Nauman’s mesmerizing and disorienting Surveillance Piece (Public Room, Private Room) (1969-70) is a lone exception. California Video gives the impression that while artists on the East Coast may have been staring themselves in the face, Californians were on the air and looking for laughs. The Getty presents a daunting amount of early video and nearly all of the works parody the forms and conventions of television with a sharp political edge and humor that directly attacks California’s culture industries of Tv and film. Suzanne Lacy’s Where the Meat Comes From (1976) and Martha Rosler’s Losing: A Conversation with Parents (1977) ape the daytime television genres of cooking and talk shows to offer scathing feminist critiques of our culture’s relationship to food and the feminine form. Tony oursler stages child-like soap operas of domestic dysfunction (Selected Works, 1978-79) and Cynthia Maughan remakes herself into endless stock characters from B-grade horror and romance films (Selected Works, 1973-78).

Chris Burden, an artist better known for daredevil performance art, was one of the most insightful and innovative artists working with television. Throughout the 1970s, Burden got on broadcast Tv every way he could: he bought airtime to exhibit gruesome performance documentation and ran a series of self-promotional, paid advertisements. The controversy around his performance piece Shoot (1971) landed him a surreal interview on Regis Philbin’s talk show, Philbin and Company (1974).4 Most infamously, Burden “hijacked” Phyllis Lutjean’s live public access television show, holding a knife to her throat and destroying the station’s tape of the incident on air (TV Hijack, 1972). No recording exists of the event since Burden forgot to hit record on his camera. The act went on the air then disappeared into the ether. Big Wrench (1980), Burden’s only piece in California Video, was originally broadcast live on a foreign language television station in San francisco. It tells the story of Burden’s doomed love affair with a broken down tractor-trailer called Big Job. Burden spins the deranged tale of his quest to purchase and then unload the big rig as he hovers superimposed over stock images of Mack trucks cruising along open American highways. In a series of mescaline-fueled fantasies about what one could do with a truck, Burden dreams of a moving museum for his work, an antiques business with his mother, and hunting down his estranged girlfriend with a blowgun. Big Wrench gives the viewer just a small taste of Burden’s television work.

If a tape of Burden’s TV Hijack did exist, one would expect to find it in the small side room of the exhibition that bears the warning that viewers may find some of the videos inside offensive. The twelve monitors crowded into the room mainly display images of men behaving badly. Paul McCarthy is up to his familiar abject antics in Stomach of the Squirrel (1973); Skip Arnold crashes about a white cube in an American flag motorcycle helmet until he knocks himself unconscious (Marks, 1986). The inclusion of several explicitly political works, such as Ulysses Jenkin’s Mass of Images (1976) is curious. It is hard to tell whether the disclaimer on the door is a joke, but through its lens, Bruce Nauman’s g-rated, fanny-wagging Walk with Contrapposto (1968) never looked so racy.

The large majority of works in this historical section of California Video appear on nondescript viewing monitors piled atop institutional-issue metal tables, separated by thick, Beuysian strips of felt hanging from the high ceiling. The hall contains the vast majority of tapes in the show and it is easy to miss a work in the crowded, media-lab setup. In their presentation the early videos appear short-changed, especially as compared to the contemporary portion of the exhibition, with its large-scale projections and elaborate installations. for example, two early works from Bay Area collective video free America give no hint of their original form. The Philo T. Farnsworth Video Obelisk (1970) was once a seven-monitor tower of switching channels. The experimental documentary The Continuing Story of Carel and Ferd (1970-75) follows porn actress and filmmaker Carel Rowe and her bridegroom, Ferd Eggan—a bisexual junky looking to get straight—through their relationship, from premarital negotiations to consummation to eventual unraveling when Ferd realizes he may not be as interested in women as he had thought. At the Getty, the work appears as an hour-long, single-channel video, but it was originally an eight-monitor display with live and recorded segments mixed on the fly for audiences. A few early videos retain their original trappings. Phillips reinstalls Eternal Frame (1975), by artist collectives Ant farm and T.R. Uthco, in all its former glory. This campy video painstakingly recreates the Zapruder home movie of the assassination of John f. Kennedy. As curious crowds form to watch and record the reenactment, they too are incorporated into the video. Eternal Frame plays on a television in a simulated period living room where each picture, memento and tchotchke in the room commemorates the thirty-fifth president’s death. The archetypal American living room becomes a shrine to both the first continuously covered media event and the technology that made it possible.

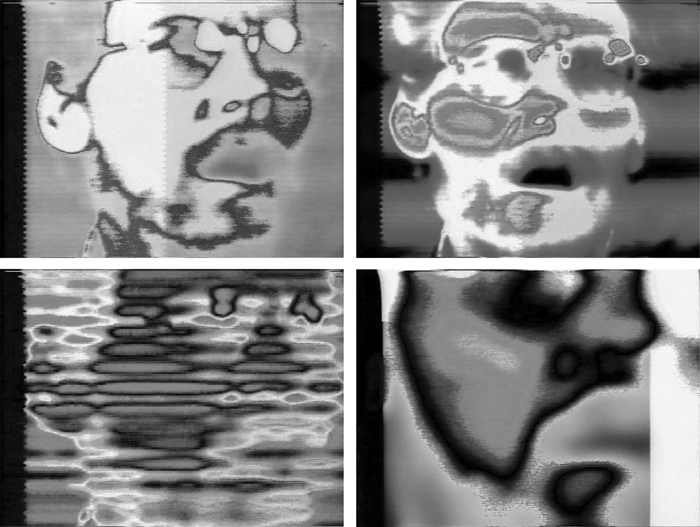

The exhibition bridges the distance between video’s historical origins and contemporary practice with a short hallway of abstract, formal works and a “video study room.” The study room, with high-tech touch screens, in part makes up for the over-crowded first hall. visitors can watch any of the exhibition’s pieces “on demand,” and see each of the in their entirety or skip around as desired. Among the abstract videos are Stephen Beck’s experimental synthesizer works from the mid-1970s. Video Weavings (1976), created without a camera using a synthesizer he invented while in residency at the National Center for Experimental Television, still captures the radical formal, technological, and aesthetic effects of its moment. originally broadcast on PBS television, Video Weavings breaks down the vertical and horizontal scans of the television screen into lattice-like color patterns, making the workings of the monitor simultaneously intelligible and mystical. More recent abstract works, however, are decidedly lo-fi. Lynne Marie Kirby’s impressionistic Golden Gate Bridge Exposure (2004), also made without a camera, is a video transfer of a reel of 16mm film exposed to sunlight and then developed. The erratic eruptions of color are momentarily stilled, creating a pulsing color field painting. In STRIP (2006), Erika Suderburg creates the look of software and digital processing by speedily panning across the edges of abstract paintings. The recent works make one wonder if the days of artist-as-technological-innovator are over.

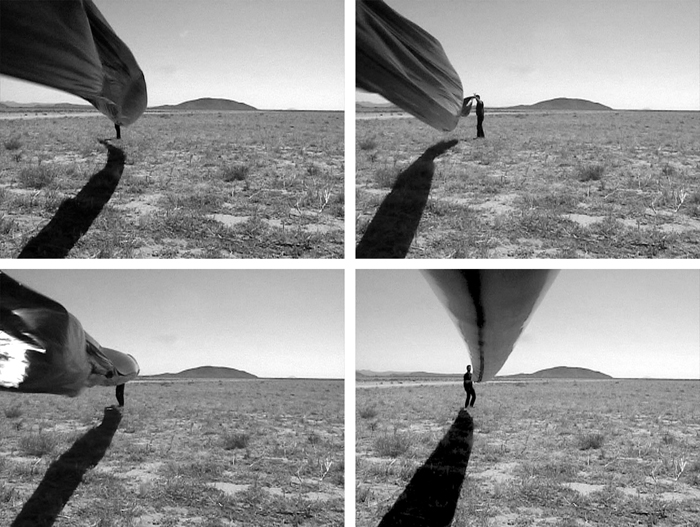

The utopian impulses of the early videos in the first half of the show seem to dissipate in the final rooms. Against the densely packed rows of monitors in the first rooms, the contemporary work appears surprisingly thin, both in number and in their material supports. The images migrate from chunky television screens to wall-sized projections, implying that in the last fifteen years video has become less like television and more like film or painting. The latter part of the show falls prey to the trap Phillips sets up in the opening: many of the works in the contemporary wing are pure technological effect—such as Hilja Keading’s continually switching, six-monitor, three-screen video of a woman wrestling with a perforated garden hose (Backdrop, 2002), or the technology seems to disappear before our eyes, as in Paul Kos’s study of light in stained glass, Chartres Bleu (1983-86). The works entertain and dazzle, but fall short of critical engagement with the medium. And in one case in particular, video really does become boring—Volcano, Trash and Ice Cream (2005), Meg Cranston’s over-blown, wall-sized, hour long projection of a melting ice cream cone. The new works appear showy and overproduced compared to the straightforward (if not unceremonious) treatment of the great works of early video. The excitement about new technologies and distribution methods in the 1970s, so present in the earlier work, gives way to encounters with technology that are alternately numbing or nightmarish. only one short clip plays of Day is Done (2005-06), Mike Kelley’s bizarre recreation of high school yearbook photos taking the form of a 365-chapter work-in-progress. The chapter shown here features a crass, trash-talking devil and screens installed facing an elaborate throne. Bill viola’s mixed media installation, The Sleepers (1992), sinks video monitors of comatose nappers in the bottoms of water filled oil drums. Radar Balloon (2005) by Jeff Cain exposes the surveillance technology that currently keeps watch over us. Cain releases a fifty-foot-long weather balloon in the Mojave Desert and stands by to watch as the military sends out unmanned Predator Drones to chase down the Ufo. Black Out (2004), Cathy Begien’s funny, deadpan narrative of a wild night on the town, tells the story of a young person passively sitting on the periphery of her own life, watching it as if it were on television.

In contrast to its neighbors, Brian Bress’s Under cover (2007) does resurrect the excitement about the transformative potentials of new technologies so present in the work of the early 1970s. Bress plays a cast of characters that seems to be pulled from both the art world and Saturday morning cartoons. on an ingenious set of trompe l’oeil backdrops and with the help of simple yet mystifying “special” effects, Bress tells a dreamlike narrative of negotiations between collector, critic, and artist, all equally clueless about what any artwork means. In between these satirical vignettes, another set of characters emerges from the painted backgrounds—otherworldly, mythical creatures that appear and disappear, multiply and disperse, and reproduce themselves endlessly. It doesn’t really matter if the critics and collectors can’t make up their minds; the art is out on its own, running rampant. Rather than being confined to gallery displays or limited edition tapes, Bress has posted his videos on YouTube, enabling him to reach audiences much larger than any museum show curator could hope for.

In the new forms of distribution enabled by streaming media sites and file sharing one can find the clearest connection to the radical practices of the 1970s. Artists’ television and public access may not have taken down the big networks or done much to change traditional broadcasting, and maybe the web won’t either. But it has, little by little, changed the way video art circulates. Bress, as well as his East Coast contemporary Ryan Trecartin, choose to distribute their work on-line. for this generation, it may not be reproduction in the mass media that verifies an object as art, as Krauss lamented in 1976, but it may be what keeps art relevant.

To write the history of a distributed form of art such as video or television as a specifically regional one is unnaturally restrictive and obscures why so many artists were excited about tape and broadcast to begin with—it travels and disperses. It’s not clear what this designation does for the Getty beside state the obvious—California, since at least the mid-1960s, has been birthplace of many great works of art (if not the birthplace of the “Californian” artists themselves.) And indeed, great institutions like the Long Beach Museum of Art have been integral in supporting and shaping this history. The Getty’s new interest in video art is in part because the medium has matured and become—like the museum’s other objects—“serious, scholarly, and classic,” in the words of Getty director Michael Brand.5 So much so that the Getty has written a new “bible” of video art, a bulky—yet surprisingly patchy and partial—tome. But it is also because early video is in dire need of preservation and restoration. Many of the tapes in the collection have not screened as much as they deserve and, without the Getty’s intervention, they would be doomed to obsolescence. one can only hope that the Getty follows Bress’s lead when they finish digitizing their enormous new collection of classic video and help to inspire a new generation of critical and politically engaged artists. Art made for the monitor and airwaves shouldn’t languish on shelves. The best way to preserve is to distribute.

Kris Paulsen is a doctoral candidate in the Rhetoric Department and the Center for New Media at UC Berkeley.