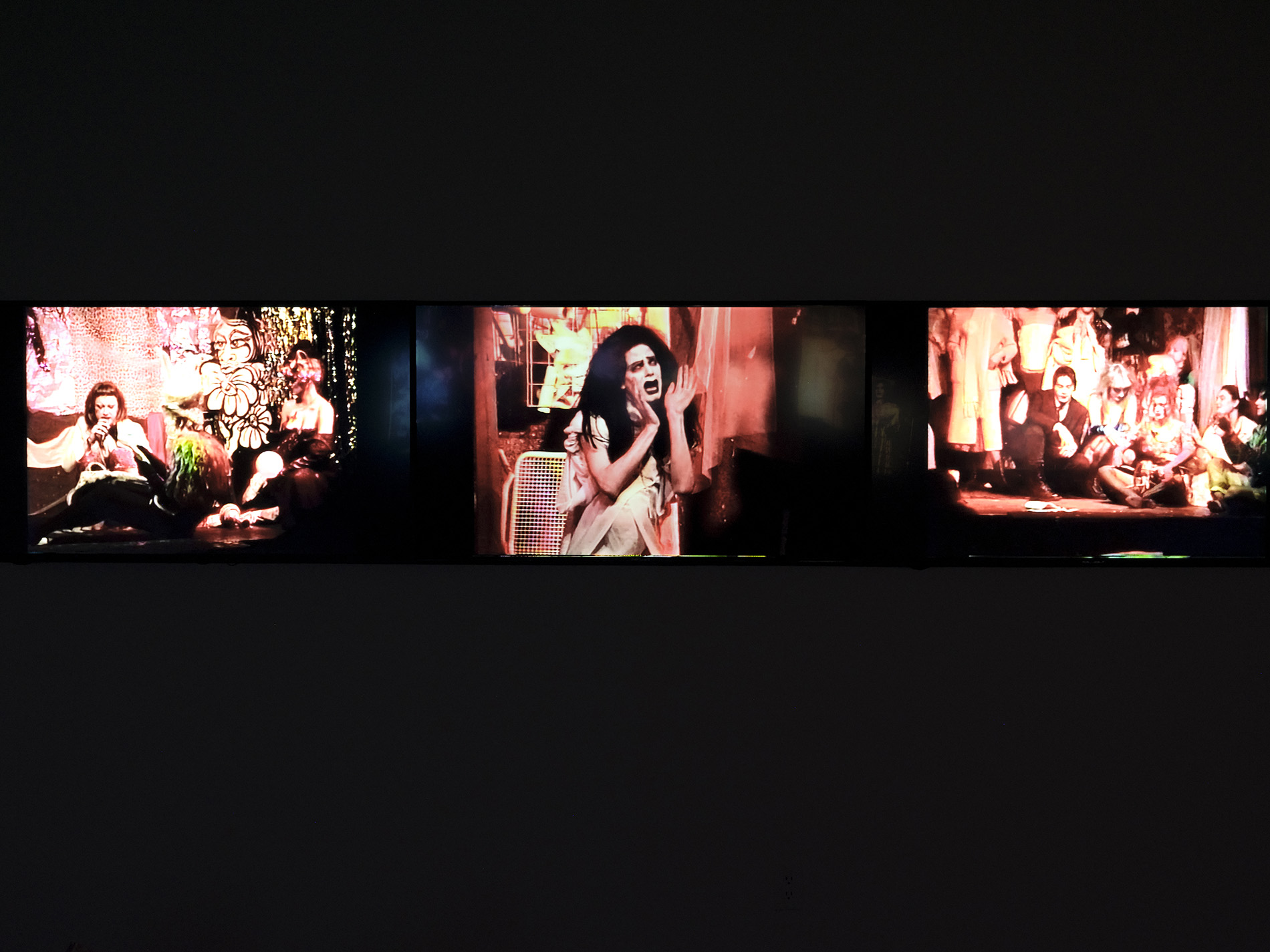

Blacklips Performance Cult: 13 Ways to Die, at Participant Inc, New York, November 6–December 18, 2022. Photo: Daniel Kukla.

Is this the rapture?1

ANOHNI sings—an emissary from the void. Her singular voice, at once oracular and ambivalent, is asking about the end of the world. Be it through the guise of tortured chanteuse Fiona Blue or the malevolent world-devouring entity known as Sinister Grey, her question hovers unanswered throughout the brief yet prolific output of the Blacklips Performance Cult, the experimental theater collective cofounded by ANOHNI, Johanna Constantine, and Psychotic Eve in New York in 1992. Known for their trademark tagline, “Bloodbags and Beauty,” which hinted at the carnivalesque mélange of elements that constituted a typical performance, Blacklips originally assembled as a loose constellation of queer misfits. Responding to the false optimism and hippie revivalism that was prevalent in NYC drag communities in the midst of the AIDS epidemic, they chose instead to cultivate an ethos of fatalism, reveling in the macabre in an attempt to reckon with a nightlife indelibly marked by decay. Every Monday night at 1:00 a.m., from October 1992 to March 1995, patrons of the Pyramid Club, the legendary Lower East Side countercultural epicenter, were presented with a brand new play. These unsuspecting audiences (initially comprised of barflies, stragglers, and wayward souls) would encounter feats of dramaturgic madness penned by a member of the core ensemble, sometimes hours before showtime, and always painstakingly executed. The Blacklips’ oeuvre would soon grow into a vast cosmogony of subversive queer performance traditions, encompassing blood-spattered agitprop, gallows humor, postapocalyptic torch song, nonlinear lip sync, riotous camp spectacle, Butoh dance, and Dadaist transmissions from the feverish depths of their kinetic mausoleum. Through this outcasts’ theater of comorbidities, a weekly confrontational exorcism would occur, of and for the recently departed.2

My life is one awful television show . . . with no reception!3

Appropriately, the Blacklips’ legacy is currently undergoing a rigorous and devoted public exhumation. Blacklips Performance Cult: 13 Ways to Die, on view at Participant Inc from November 6 through December 18, 2022, was the third installation curated by ANOHNI to explore materials from the Blacklips’ archive. This iteration comprised video documentation of twenty-nine plays presented simultaneously without sound. Each day of the show’s run revolved around an audible screening of a single play. The exhibition preceded the publication of Blacklips: Her Life and Her Many, Many Deaths, which was presented in the form of an excerpted prototype on a gothic lectern upon entry, and the release of the double LP compilation Blacklips Bar: Androgyns and Deviants—Industrial Romance for Bruised and Battered Angels, 1992–1995. The archival sprawl at Participant, presented with a keenly deceptive minimalism, was sensorially overwhelming and staggering in scope, functioning as both a bedeviled hall of mirrors and a wildly oscillating site of mnemonic activation. The occult nature of the Blacklips’ repertoire, with its recurring themes of divination and necromancy, is subject to further transfiguration when accessed, or reanimated, through what Jacques Derrida refers to as both the “unknowable weight” and the “spectral messianicity” of the archive.4 In other words, it felt to me as if the ghosts and the machines on display were inseparably entangled, their edges blurred and replicated for ever-shifting iterations of posterity, myself included. To encounter this deluge of audiovisual ephemera, itself the product of a ritualized desire to cheat, circumnavigate, or resignify the parameters of mass death and contagion, is to bear witness to multiple demises and resurrections, mimetic or otherwise.

Blacklips Performance Cult: 13 Ways to Die, at Participant Inc, New York, November 6–December 18, 2022. Photo: Daniel Kukla.

The liminal space that exists here, between the original Blacklips’ performances and their subsequent reordering through the mechanisms of the archive, twists the restless wraiths of queer nostalgia into new shapes in the midst of contemporary infrastructural failures and continuing global health crises. Derrida’s assertion that the archive posits “a responsibility for tomorrow” is of particular interest here. In plays such as The Birth of Anne Frank (1994), in which a dour Anne Frank is born from a tumescent wound in an American businessman’s head, the irreverent pastiche of intergenerational trauma is utilized to explore what Okwui Enwezor calls, in the context of the morbid media spectacle depicted in the screenprints of Andy Warhol, “the psychic ruptures in the American collective imaginary.”5 By continuously mining and repurposing the “popular” lexicon of carnage, seen elsewhere in their staging of Jack the Ripper (1993) and Swiss Family Donner Party (1993), Blacklips pushes for an elliptical and arguably ouroboric interpretation of world history, in order to draw attention to the grotesque negligence of the United States’ response to AIDS, while further troubling the Western preoccupation with death as entertainment. In doing so, they avoid the commodification that spurred Anne Wagner to refer to Warhol’s screenprints of police violence against Black protestors as “caught between modes of representation: stranded somewhere between allegory and history.”6 Rather, the Blacklips’ mythos is mobilized across epochs through its commitment to communal grief and capacity for world-making; allegory and history are dismembered and eviscerated, only to be stitched, sutured, alchemized, and perpetually transubstantiated.

Is this the rapture?7

In certain plays, the question of the rapture is posed as mordantly rhetorical, with the sneer of a jaded executioner or the bitter nonchalance of Peggy Lee asking, “Is that all there is to the circus?” At other times, the question is crooned with celestial detachment: the musings of a fallen angel surveying the ashen drudgery of her own funeral. The rapture is then, now, two weeks from yesterday, so over, and whenever you have a moment. This ongoing invocation of eschatological malaise is given further dimension when echoed across the quotidian atrocities of modernity, reaching through time and space to address the nation-wide resurgence of anti-trans legislation, innumerable mass shootings, and impending ecological collapse. Furthermore, the unstable materiality and implicit degeneration of the archive, susceptible as it is to mold, humidity, and accruing layers of literal and ontological dust, enhance the mystical undertones of the Blacklips’ prognosis, beholden to what José Esteban Muñoz identifies as “the hermeneutics of residue.”8 The mere existence of this work is already an act of defiance, of underdog survival, yet it is only through its subsequent dissemination and the inexorable passage of time that it acquires the aura of prophecy for future generations of the disenfranchised.

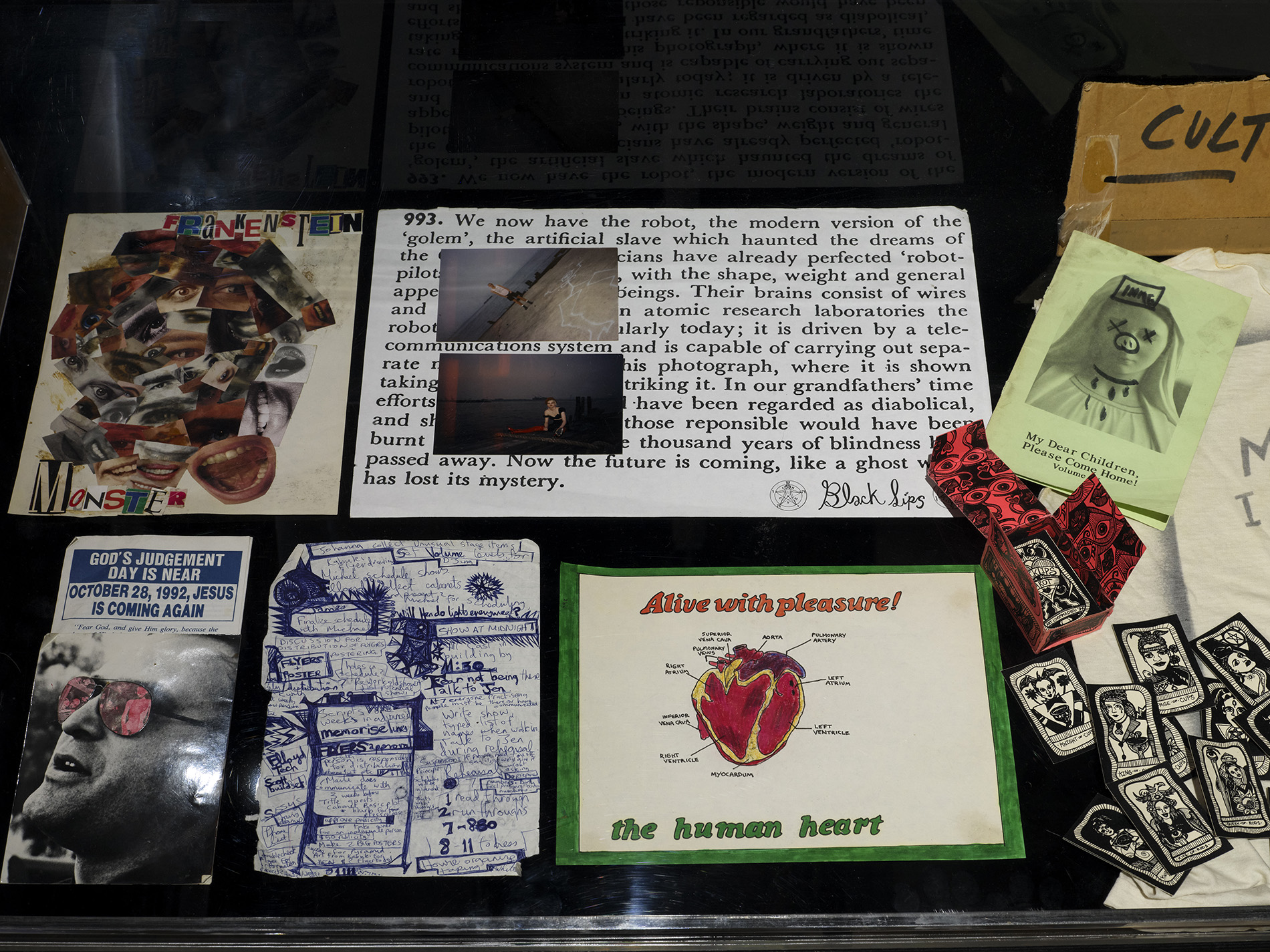

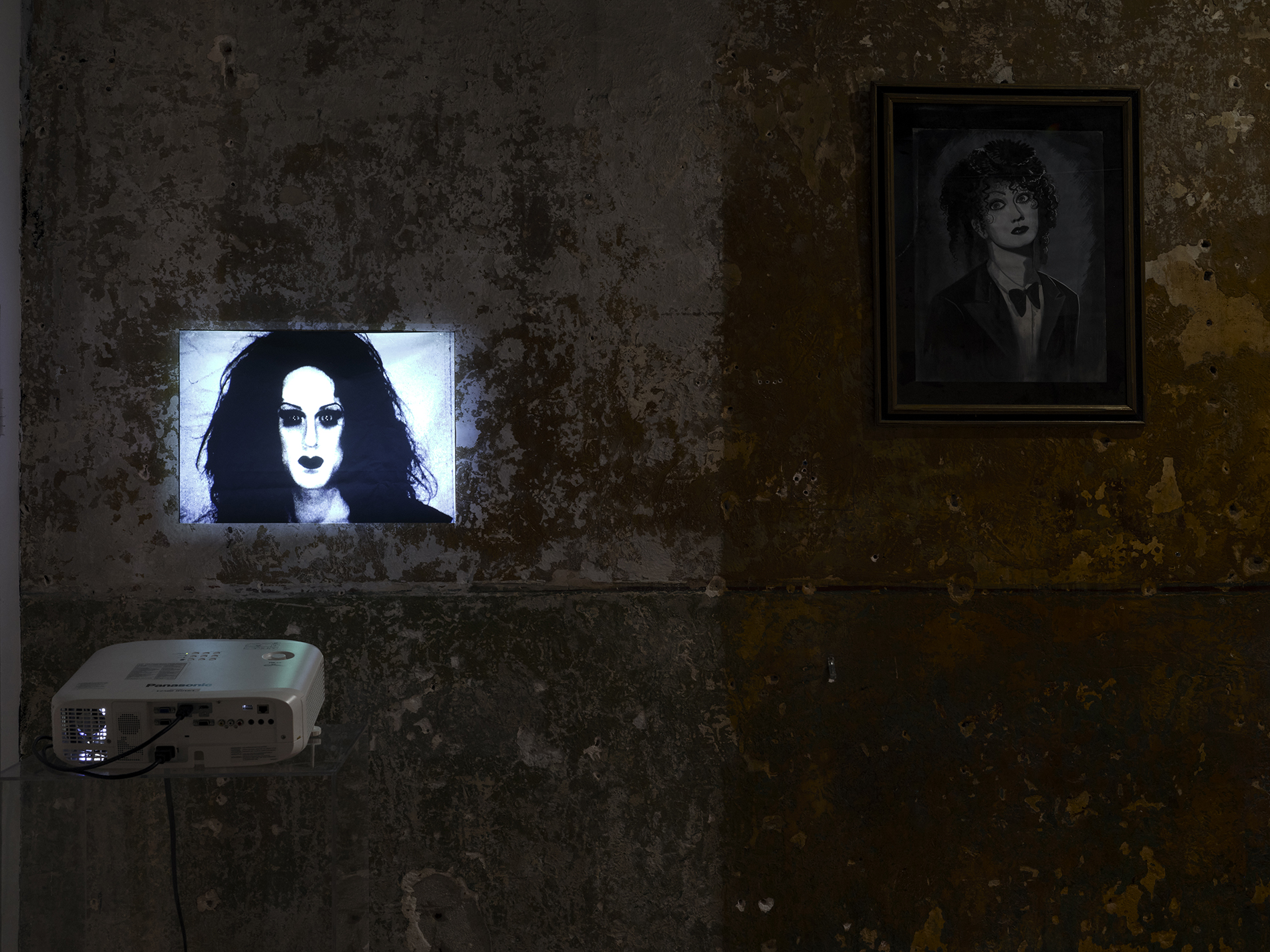

Blacklips Performance Cult: 13 Ways to Die, at Participant Inc, New York, November 6–December 18, 2022. Photo: Daniel Kukla.

Upon multiple visits to Participant, it felt to me as if I had happened upon a memorial service for a lover I had met only in my dreams; my conscience was subsumed by a hazy and intangible yearning that was not entirely my own. I wouldn’t categorize it as Stendhal Syndrome necessarily, although at times it did leave me thoroughly flustered. I jotted down “ekphrastic déjà vu” in my journal at one point, but that felt a bit banal. I could venture to describe this sensation as a form of saudade, a word of Portuguese origin with no direct English translation that conveys the presence of absence, or the desire for a moment or person that may have never existed.9 I would sit on the floor in hushed contemplation, attempting to pay my respects, inevitably swept away by the bustling cortege of messy funeral divas that occupied these video recordings, as they blabbered and retched and histrionically wept into an endless succession of open caskets, routinely stopping to pantomime outlandish acts of sodomy along the way.

The commingling of ribald humor with abject terror and hyperbolic gore has historical precedent in the Grand Guignol theater of early twentieth-century France; the resulting emotional effect on the audience was dubbed a “douche écossaise, a hot and cold shower.”10 Other salient influences that come to mind included the depraved psycho-biddy parodies of Charles Ludlam’s Theater of the Ridiculous, the LSD-doused burlesque of West Coast rapscallions The Cockettes, and the cheeky torture odysseys of Eleven Executioners, Munich’s first cabaret (c. 1901–4).11 Perhaps it was the “unknowable weight” of these lineages of subterranean performance, this undying commitment to queer ancestral worship, that added to the sheer immensity of my experience and catalyzed the sensation of saudade. If so, this would extend to somatic gestures and methods of inhabiting one’s physicality, the notion that the body itself operates in an archival capacity and retains a catalog of feeling. In numerous plays, Johanna Constantine cycles through a spasmodic repertoire of danse macabre, mimicking the throes of prolonged torture and the strictures of rigor mortis. Adorned in vestments made from flattened roadkill, codpieces fashioned from deer skulls, and repurposed industrial scrap metal, Constantine would channel the essence of a nuclear reactor or a mythical beast with infernal aplomb. The “unknowable weight” of the archive is present in these gesticulations, as well as the rehydrated bovine entrails that were frequently deployed for mock disembowelment (adhering to the John Waters school of practical effects) and flung with reckless abandon into the unsuspecting crowd. It goes without saying that body horror is a prominent and unifying motif; the terrors of uncontrollable transformation and risks of infection permeate the Blacklips’ collective id. In the Blacklips’ retelling of Frankenstein (1993), Dr. Frankenstein’s laboratory is overrun by bimbo junkies who sourly pantomime to “Sister Morphine’’ while sharing needles, Igor performs a sassy rendition of “Stormy Weather” in order to conjure a lightning bolt, and Frankenstein’s monster is tortured in an irradiated forest by the Queen of the Lepers. The earthly limitations of the body are under constant interrogation.

Blacklips Performance Cult: 13 Ways to Die, at Participant Inc, New York, November 6–December 18, 2022. Photo: Daniel Kukla.

No one can see the fruits of my muscle movements. To pull my body into shapes that humans can understand . . .12

Running parallel on each side of the gallery space were rows of video documentation. Fourteen screens on each lateral wall led to the larger posterior screen, on which the daily viewing would take place. When seen as a multichannel Gesamtkunstwerk, these images, looped and digitized, became an oneiric swirl of Giallo-cinema-indebted colors, incidental polyrhythms, and aleatoric confluences of movement and light.

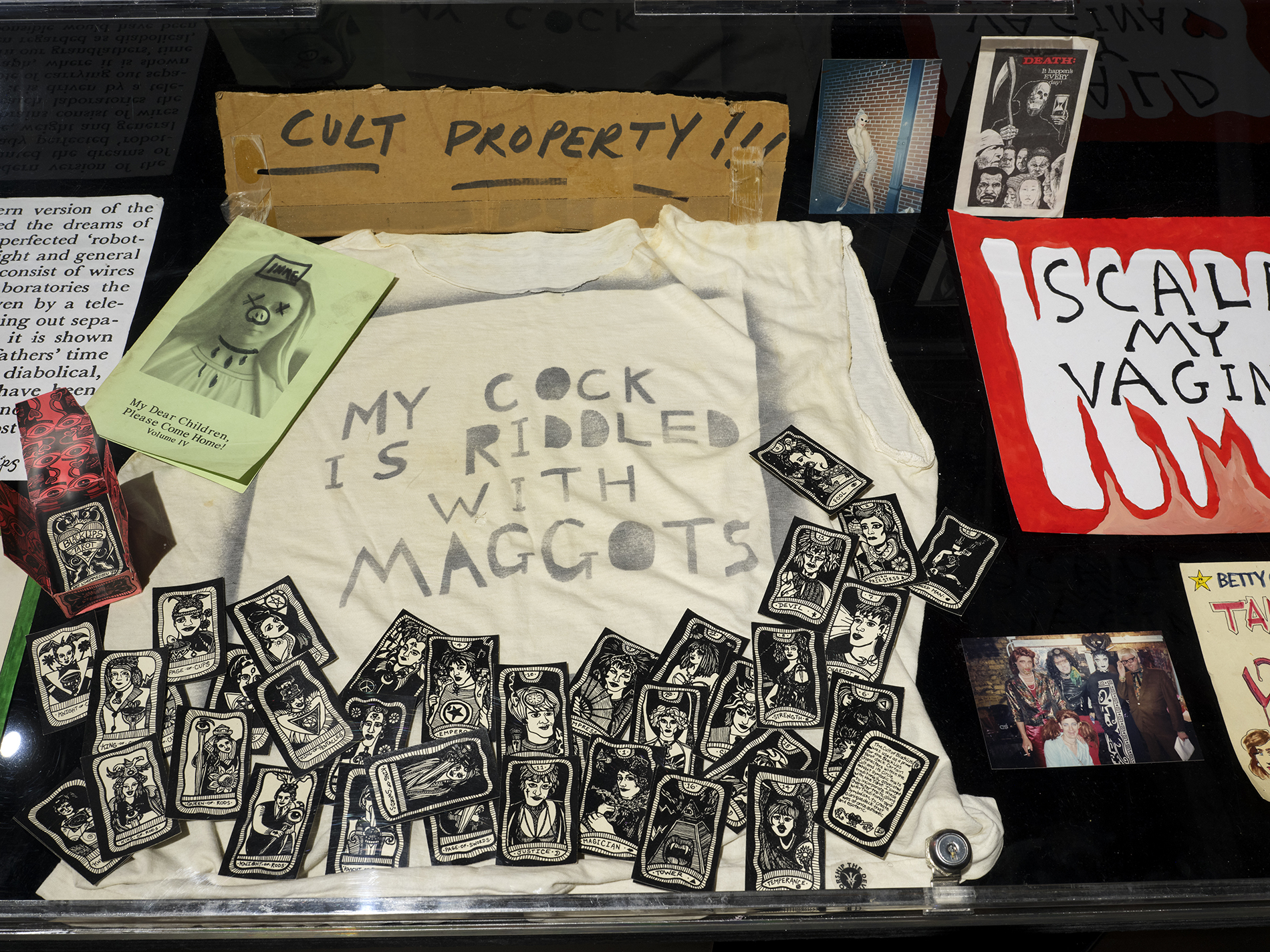

This pervasive mesmeric undercurrent was anchored by a thin and angular central table that spanned the length of the room. A series of corresponding scripts, some xeroxed, some annotated by hand, were encased here, affixed with dangling metal tassels reminiscent of metronomes in their unassuming symmetry. This notion of “keeping time” felt ironic in retrospect, given the temporal disjunction that would occur upon exiting the building and the realization that the semblance of a “fixed” chronology was less a matter of fact and more a matter of incisive curation, which effectively conjured the purgatorial ambience that a live Blacklips show might produce. In this sense, it is fitting that Blacklips created their own tarot deck with illustrator Art L’Hommedieu, also on display at Participant, featuring avant-garde luminaries such as Klaus Nomi and Divine as sacred archetypes. To canonize these artists (while adhering to a type of queer transvaluation inspired by the works of Jean Genet) is to reinscribe the unseen systems of the metaphysical world onto a cohesive taxonomy. The bespoke tarot, while doubling as an esoteric “archival impulse,” is also a vessel of atavistic immanence, a means of maintaining an active dialogue with the spirits of the past, present, and future, both real and imagined.13

Blacklips Performance Cult: 13 Ways to Die, at Participant Inc, New York, November 6–December 18, 2022. Photo: Daniel Kukla.

We do this every week. After all the excitement I have an empty feeling.14

A sly and unavoidable meta-awareness punctuates these performances, creating an uncanny effect when viewed outside of a live context. Be it Brechtian alienation or eerie coincidence, certain winks and proclamations catch one off guard in their seemingly conspiratorial allegiance to a future audience. The iconography of the maggot wriggles along this threshold, appearing in myriad productions as exaggerated prosthesis, omnipresent narrative device, unlikely symbol of healing and regeneration, and even as enamel pins worn on the lapels of featured performers. Amongst the miscellaneous ephemera housed in the vitrines of Participant’s back room was a shirt worn by ANOHNI to Wigstock shortly after the death of American activist and transgender drag artist Marsha P. Johnson; it read “MY COCK IS RIDDLED WITH MAGGOTS,” in a provocative embrace of stigma and perceived virality. This ongoing dedication to the aesthetics of decomposition was ethically aligned with the interventionist politics of ACT UP and a challenge to ongoing issues of “positive” representation, particularly in advertisements surrounding antiviral medication, those that Douglas Crimp referred to as “images of hunky men climbing mountains.”15 The maggots squirming around in the Blacklips’ multiverse imply a militant zombification, an undead coalition eating away at the tyranny of widespread cultural amnesia, while concurrently intimating a transference of power from the hegemonic to the revolutionary. Impervious to the machinations of the state, the maggots are the rising insurgents of the counterarchive, inching across the exposed retina of an exquisite corpse or the chipped plastic visage of a stage mannequin.

Every now and then we make history.16

Psychotic Eve, Swiss Family Donner Party, January 11, 1993. Video still.

In the play Clayworld (1993), written by Lily of the Valley, Blacklips mainstay Kabuki Starshine, known for her otherworldly glamor, impeccable makeup skills, and prodigal lip-syncing talent, saunters onstage with a mystical lethargy. Emerging from a plume of fog suggestive of opium smoke, Kabuki is languid and aqueous, the contours of her silhouette reminiscent of an Aubrey Beardsley illustration, as she flawlessly enunciates to “Video Killed the Radio Star,’’ by The Buggles. In Camp Talk and Citationality: A Queer Take on “Authentic” and “Represented” Utterance, Keith Harvey posits, “Through citationality, camp speakers allude to and manipulate specific devices of interaction in ways that problematize the contribution of these devices to conversational meaning. The result is a conception of the utterance as echoic and ironic, one which creates a specific context of conversational bonding between (queer) interlocutors.”17 In the work of Blacklips Performance Cult, citationality expands to include the storied tradition of the lip sync, itself a charged vessel for interlocking lineages of queer expression, corresponding to Gabriella Giannachi’s claim, “Oral histories, rituals, and gestures are all strategic for the transmission of knowledge among communities that do not traditionally have archives or those privileging physical forms of transmission.”18 The commitment to innovative modes of linguistic and aesthetic subterfuge to avoid persecution is a prominent feature of the queer archive; it manifests in cryptolects, such as Polari, and in the semiotics of the handkerchief code. When the fathomless archival expanses of this secret history are given some discernible shape, gravitating away from formlessness and the immaterial, they are haunted by the residue of this transition, the detritus and ectoplasm that gathers in the interstices of the obsolete technologies and archaic institutions left behind. Each monitor in 13 Ways to Die is an undead archive unto itself, an obsidian scrying mirror burbling with arcane wisdom, enacting the ritual of necromancy while simultaneously pointing towards its impossibility. The Cabaret of the Necropolis is performing to a packed house: the ghosts of those who never existed sitting alongside the ghosts of those who always did.

Is this the rapture?19

Blacklips Performance Cult: 13 Ways to Die, at Participant Inc, New York, November 6–December 18, 2022. Photo: Daniel Kukla.

Over a cascade of phantasmal organ, ANOHNI sings her rendition of Gloria Gaynor’s “I Will Survive.” The other ANOHNIs in the room sputter and revolve on their grainy axes, living and dying, uninterrupted.

Kamikaze Jones is an interdisciplinary artist whose work explores extended vocal technique, queer hauntologies, and ritualized erotic transcendence. He is the arts editor of WUSSY Magazine.