Mihalis Tzanoulinos carefully manages the turning of an ancient marble block, Athens, 2016. Photo: Allyson Vieira.

Allyson Vieira and Brooke Holmes first met over a long lunch in Athens in the summer of 2016. Holmes was doing a series of artist interviews for her project Liquid Antiquity, commissioned by the DESTE Foundation, and Vieira was pursuing her own interview project with the master marble carvers working on the restoration of the Acropolis. The interview didn’t happen then, but the two kept in touch. In 2019, on the occasion of the publication of Vieira’s On the Rock: The Acropolis Interviews with Soberscove Press, Holmes proposed they have a conversation about their convergent interests in ancient Greece, the long and troubled history of classicism, dialogue as an aesthetic medium, and the different materialities of sculptures, buildings, and books. They have edited the following collaboratively for length and clarity.

BROOKE HOLMES: In the last sentence of your book, On the Rock: The Acropolis Interviews, marble carver Petros Georgopoulos says, “I’m not sure if we, the modern Greeks, give the honor that we should to this civilization, Greek civilization, but it’s something globally established. It’s why you are here and why we are talking about this.” When you started this project, how would you have answered, “Why am I here, and why are the marble carvers and I talking about this?” By “this” I mean the craft involved in restoring, or caring for, the Parthenon. And how would you answer this question now that the book is published?

ALLYSON VIEIRA: I recently saw artist Nao Bustamante speak, and she discussed what she calls brain burrs: small ideas that pop up and don’t go away. Eventually you just think, “This thing is stuck in my mind; I have to make it.” I guess I had a brain burr.

I grew up in the suburbs. There was an undeveloped lot next door full of tall grass that went over my head, and I used to play there with my dad. Then one summer, when I was, I don’t know, five or six, bulldozers arrived and turned the ground over. Where my play field of tall grass had been were big mounds of dirt and sedimentary rocks.

At first I was devastated—I’d lost a place where I’d loved to play—but soon I went back to explore. I spent that whole summer intrepidly climbing up and down those dirt mounds alone—they felt like mountains—sorting through rocks. I broke them apart with other rocks, and discovered fossils inside: blades of grass, bits of plant matter, ferns. These weren’t animal fossils, nothing fancy, but still, finding fossil imprints of grass within slate that a six-year-old could split open was pretty exciting. The shoebox of fossils that I collected that summer is the only thing I wish I still had from childhood.

HOLMES: When I was growing up, my grandparents lived in the country. Around their farmhouse they had ten acres of land that they rented out. The farmers often planted peas, and after the harvest we would go gleaning.

One day I found a little porcelain doll arm in the dirt. I had never found anything manmade in the dirt, and I’ll never forget the smooth feel of the arm. I was actually thinking about that arm earlier today, because peas are in season at the farmers’ market, but before now I hadn’t made the connection with archaeology.

VIEIRA: All my childhood and teenage years, I wanted to be either a paleontologist or an archeologist. Deep time, whether thousands, millions, or billions of years, always interested me. I ended up going to art school. But my interest in deep time is still probably the most significant force motivating my sculptural practice, whether it’s thinking about time reaching backwards on a geologic scale, or the long timeline extending forward from this moment. But those two vectors are not as clear-cut as they may seem, and I love getting caught in complicated temporal eddies.

I first visited Athens in 2007, and I think it sealed the deal as far as me being a sculptor, someone invested in reading and creating objects. Greek antiquities look different there; I could see under, around, beneath them. And I finally understood the notion of site in a concrete way. I’d never been anywhere before where the passage of time marked by sequential built human environments is physically visible like it is there, all in one place, in one glance. Athens is a millennia-deep layer-cake of cities, with the contemporary, living city on top, and the future world always just out of view.

HOLMES: I want to go back to the “we” that Petros names at the end of the book. You’re very scrupulous about not inserting yourself in the text and letting your subjects speak. I know that you’ve thought a lot about Studs Terkel and the ethics of the interviewer. But the language of the interviews naturally has a dialogic quality. Petros says, “It’s why we’re here”—that is you and him together. And another of the carvers, Giorgos Aggelopoulos, says, “You’re a sculptor. You’re one of us!” So, I’m curious about how you see this “we.”

VIEIRA: That’s a tough question. I was an outsider, an American woman, not trained in marble carving. I wasn’t sure if I would be able to build a “we,” or if the conversations would be stilted. So, I was touched to feel a sense of community from them. That was due in large part to my friend and facilitator, Polyanna Vlati, their colleague and a trained carver herself. She gave me entrée into their world. And maybe also because I approached them as a fellow maker who wanted to learn.

But I think what Petros was getting at specifically are the contemporary echoes of philhellenism’s strange reciprocity: how the West’s concepts of the ancient world, the inordinate value that they invested in the idea of the ancient Greek “ideals” and cultural ancestry was projected onto nineteenth-century Ottoman Greece via support for the Greek independence movement, then adopted by influential Greeks in service to their nation building, and has had an outsized influence on the contemporary Greek national identity to this day.

That’s a too-simple version of a complex history, but I think he’s referring to that set of values, or more specifically, value formation. It’s like, “That’s why you’ve come to this monument. That’s why I’m rebuilding this monument.” Right? I think that “we” is reflective of a kind of Greek double consciousness. He’s rebuilding the monument because I, the foreigner, am coming to it, but also because it’s important to him as well. And yet, how much of that valuation has been adopted from the West’s imposition?

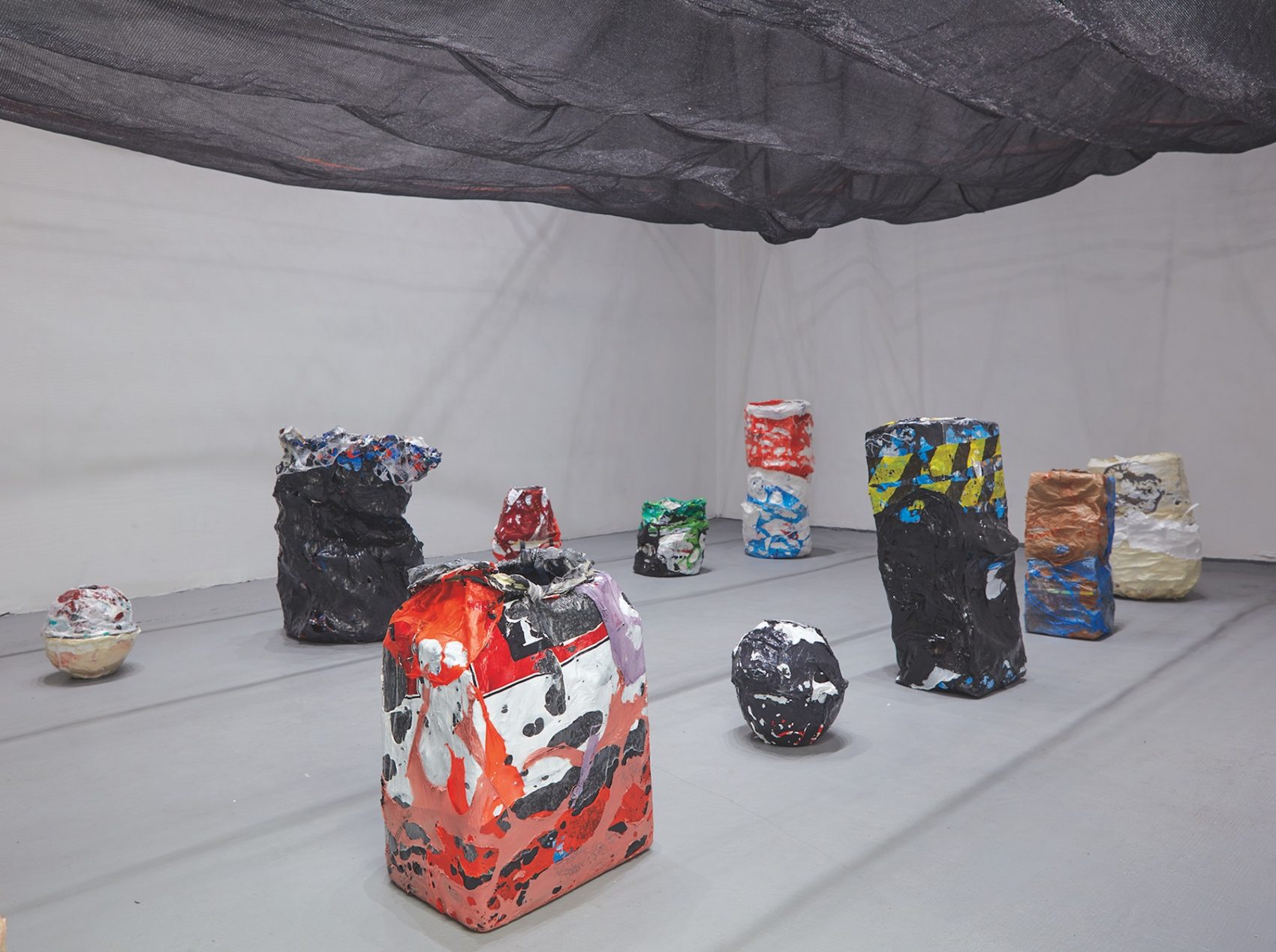

Allyson Vieira, A Pot to Piss In, Klaus von Nichtssagend, New York, February 18–March 26, 2017.

Top: Strategic Foresight, 2017. Construction debris netting, thread, 118 × 224 × 90 in.

Bottom: Vessel #13, 17, 20, 16, 2, 12, 19, 10, 8, 15, 2017. Plastic, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist.

HOLMES: What was it like to be standing inside the Parthenon looking out at the tourists?

VIEIRA: Between 2007 and 2014, I visited the site four or five times as a tourist myself before I ever went in. I made two video pieces of the workers working and took countless reference photos prior to meeting them. In 2014, the gallery I was working with introduced me to an awesome young carver, Nikiforos Samson, who took me on a tour. But the view from the literal inside looking out, I guess I don’t even remember if I looked out! Really, why would I when there was so much new to see inside? I thought, “I have to absorb everything I possibly can in this moment.” Inside, Nikiforos introduced me to Polyanna. They took me around and showed me what they were working on, their favorite spots, including the hidden Ottoman spiral staircase to the top. Suddenly, this day that started just like any other day turned into a day in which I was standing on the top of the Parthenon! I didn’t think that I would ever be up there again, so I tried to be in the moment.

After spending another exciting day with them at the ancient quarry on Mount Penteli, just northeast of Athens, I went home to New York. My brain burr couldn’t be ignored anymore. I read scholarly texts on the restoration, but the difference between what I was finding there and what I had just seen firsthand was vast. The materiality, community, and embodied knowledge were missing. I remember sitting in the tiny shed inside the cella that serves as the workers’ break room, watching a guy methodically file his mandrakás (hammer), while he’s smoking cigarettes, chatting, having coffee, and I’m thinking, “Where do I learn about that?”

HOLMES: The marble workers you interview are working long after the transition of the classical ruin into an object of academic study. Some of your interviewees talk about this, how they have basically been edited out of the scholarly picture. At the same time, the work of the marble carvers is different from an academic doing research. It’s a different way of knowing, with different traces in the material record—traces in the objects themselves.

VIEIRA: That’s true. I do want to say that YSMA, the Acropolis Restoration Service, has been meticulously documenting the restoration in scholarly ways.

But I wanted to learn everything I could about the carvers, and since I couldn’t find any texts out there, I decided to take the project on myself. And I was personally excited by the idea of the re-gesture. The carvers are re-gesturing the same gestures that were made on the same material, on the same site, 2500 years later. The new marble is taken from the opposite side of the same mountain as the original Acropolis marble, Mount Penteli, from the same vein, so there are tantalizing continuities, but the way time is working there is less straightforward. I wanted to explore how the carvers experienced that sort of folded-time continuity.

HOLMES: Yes, the carvers often talk about their ancient predecessors as if they were in the present, or even the future. The past is a kind of horizon of possibility.

VIEIRA: I often revisit George Kubler’s The Shape of Time, and he mentions the idea of “things” as “fossil actions.” He only uses the phrase once, but it has had an outsized impact on the way I think about gestural traces on materials, whether in my studio or on a construction site. That the object, the “thing,” is the sum total of the actions used to create it, a “fossil” of them, remains a powerful concept for me. Kubler connects the absent maker, the specific person or people, with the present object. The re-gesturing within the Acropolis restoration complicates Kubler’s concept beautifully while also proving it, in a way.

HOLMES: How does the re-gesture complicate Kubler’s concept? Is the re-gesture creative in the same way that the gesture is?

VIEIRA: Because they’re building something that has to function (as were the ancient builders), there is a right way and a wrong way to do the work. Creativity is and was happening within problem-solving, not with expression or interpretation. When you try to recreate something material in the way that it previously existed, there’s a physical re-inhabiting of gestures. The object that they’re currently creating, the Parthenon, is a fossil of their contemporary actions, their re-gestures, as the ancient one was of the ancient actions, but now the hybrid ancient-contemporary object straddles a sort of split time. Maybe even a kind of time travel?

HOLMES: How is the relationship to ancient technique, ancient gesture, changed by new technology?

VIEIRA: The word “new” is tough to apply here. Ancient techniques underlie their contemporary work and new technology is used in concert with and in service to them. Is a chisel that was reverse-engineered from 2500-year-old chisel marks new or ancient? To this day the final surfaces are all done by hand; the Acropolis workers may use a giant saw to plane down a massive block, but they still use a mandrakás and láma, a type of flat chisel, to bring it to its final surface.

Because hand carving has never fully ceased on Greece—particularly on the island of Tinos, home of the marble carving school where fourteen of the fifteen people I interviewed trained—they’re keenly attuned to the material, the technique, and the traces left on the stone. Karolos Megoulas, a retired carver and Tinos native, told me, “On many ancient marbles, we saw that two carvers had worked on one marble. . . . How could we tell? Because you have one way of working and the other guy worked differently.”

The essential marble carving tools: molívi (pencil), metró (folding rule), kopídhi (pitching chisel), velóni (pointed chisel), dislídiko (small toothed chisel), fagána (large toothed chisel), láma (flat chisel), mandrakás (hammer), and píhi (parallel straightedge), Athens, 2016. Photo: Allyson Vieira.

HOLMES: Yes, we often think about work done by hand as the most traditional in the sense of enacting its fidelity to the past. But as Karolos says, hand carving also preserves this very particular embodied intervention in the object. In that sense, it can seem different from the use of advanced technologies, say in archaeology and conservation practices. The hope with those technologies is often that they’ll minimize the interference of the situated, unique worker operating them.

But still, a new technology is also a discontinuity in a tradition of knowing, in the sense of a situated intervention. We talked a lot about how marble carving is a tradition of embodied knowledge. I wanted to ask you, as a sculptor fascinated with tools and materiality and re-gesture, how does your book work as a new technology in this tradition? You had said that you couldn’t find any books on the marble carvers, so you created a book that’s a kind of record of their work and their craft-knowledge. But the book is also a totally different technology than the technology used to produce and apply the knowledge over the centuries. It’s a different trace in the record.

I was just working on Pliny’s Natural History, the first Roman encyclopedia, this morning, and Pliny raises this same question. In his discussion of pharmacological material, he says, “I want to do something useful. I want to create a manual, because my fellow Romans do not know” what he calls “the means of life.” So, he created the encyclopedia as a record of useful knowledge. And people have used it that way. But then people have also realized that you can’t really take this to your garden and figure out what is what. You really need someone there. It’s like the book is trying to transcribe useful knowledge—knowledge for survival—but it’s also textualizing the very inability of the knowledge to surface in the text alone.

Allyson Vieira, Cortège, installation view, Laurel Gitlen, New York, February 27–March 24, 2013. Foreground: Weight Bearing III, 2013. Background: Weight Bearing I, 2013. Drywall, screws, steel, 74 1⁄2 × 64 1⁄2 × 22 in. each. Courtesy of the artist.

VIEIRA: Totally. The marble carvers were sometimes frustrated by being forced into language when describing their technique. Often somebody would try to model a technique, gesturing with whatever objects were at hand, or say, “We’ll just go up to the Acropolis, Allyson, and I’ll show you how it’s done there.” And I’d say, “Please, try to describe it in words—I can’t remember and transcribe your gestures!” I would explain that this project wasn’t just about my learning, but also about communicating their stories and knowledge to a larger audience by becoming part of the textual record.

But as a sculptor, I empathized with their frustration with language. I feel like I communicate best via objects, and what’s said in those objects remains untranslatable into verbal or textual language. Otherwise, I’d be a writer.

HOLMES: But you made a book. Do you see the book as an object, as a kind of sculpture, or artwork?

VIEIRA: Right. Ironically, here we are talking about a book! But the words are the carvers’. I just collected and assembled them. And though the book emerges from similar interests as my art practice, it’s not an artwork, or even an “artist’s book.” It’s a nonfiction book, and I’m interested in how it exists within that world, which is new to me.

So, I’m an artist who created a nonfiction book and you’re a nonfiction writer who curated an exhibition. We’re really not staying in our lanes here! Based on our conversations about your project, Liquid Antiquity, I know we have different instincts about how we use text and objects.

HOLMES: Yes, well, when we first met to talk about that project, you said, “What? There aren’t even any objects in this show? What’s your problem?”

VIEIRA: It was an unusual exhibition because it was so deliberately immaterial. An exhibition with no objects, but eventually there was going to be a book as a kind of an object? I couldn’t wrap my head around it!

HOLMES: Yes, this idea of the book as anti-object was one of the stunts of the exhibition. Instead of curating an exhibition of antiquities, we—the Athens-based curators and critics Polina Kosmadaki and Yorgos Tzirtzilakis; Dakis Ioannou, at DESTE, who commissioned the project; the book’s coeditor Karen Marta; and I—asked what it would mean to make an exhibition of “antiquity.” We started by making the book the site of the exhibition. Like in your project, conversation was central in Liquid Antiquity. The objects of the exhibition were the dialogues with the artists printed in the book. The installation in the museum, which featured video versions of the interviews, functioned like a catalog to the book-exhibition. They were the terms that the critics and historians and scholars submitted for a new lexicon of classicism that gets mobilized in the title essay. The scrambling of time was crucial, not just at the conceptual level but also at the formal level. The visual essay in the book, which was the brainchild of Takaaki Matsumoto, Amy Wilkins, and Karen Marta, was a juxtaposition of contemporary and classical art, and the book is organized like a reference work, in a nonlinear way.

The question became, How you can put the work of valuing a past, especially an ancient or “classical” past, on display? Classical is a value term that behaves like a done deal. Even critique can reproduce this sense of value as already made. How can we think differently about that work of valuing? How can we make it more liquid? I came to think about the project as an exhibition about the relation with the past.

One of the pitfalls of the ways we have for talking about “classical antiquity” and the present is that we don’t have a rich enough conceptual vocabulary. We get caught in these binaries. It’s all historicism, or it’s all presentism. It’s an authentic, pious reproduction of the past, or it’s creative appropriation. You can see this kind of binary in, say, the reception of Cy Twombly’s engagement with Greco-Roman antiquity. You end up with two Twomblys. The cool Twombly is the Twombly who’s bored in Latin class, not the Twombly who went to Italy and lost touch with the American avant-garde. Twombly can be saved for a counter-canon if we see him as entirely ludic or antiestablishment or iconoclastic. I would ask, instead, what would be a concept that would help us get at the complexity of Twombly’s relationship with antiquity? I just finished an essay on his group of paintings about the final days of the Trojan War, Fifty Days at Iliam (1978), for an upcoming exhibition on Twombly and antiquity at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, and I proposed error as a concept that might capture some of that complexity.

Liquid Antiquity: Conversations (interview with Paul Chan [top] and Jeff Koons [bottom]), installation view, commissioned by the DESTE Foundation for Contemporary Art and designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Benaki Museum, Athens, April 4–September 17, 2017. © Diller Scofidio + Renfro. Photos: Matthew Johnson.

VIEIRA: I’m so glad you mentioned Twombly! Seeing Fifty Days in the Philadelphia Museum of Art changed the entire trajectory of my art practice. But what do you mean by “error”?

HOLMES: Twombly pointed out that the title has an error no one notices: He writes “Iliam” not “Ilium.” The “a” is a nod to Achilles, whom he’s obsessed with. It’s error as creative intervention. I didn’t want to just accept Twombly’s terms or “correct” his error—I didn’t want to play the classicist—but rather to use the idea of error as errancy, as displacement or an aleatory relationship to an “original” that’s warped by time and embodiment. So I read the cycle through another “error”: the Iliad is conventionally thought to be a poem that takes place over fifty-one, not fifty, days. I read the first painting, Shield of Achilles, as an extra “one” that swerves away from the closed, round numbers of ten or fifty into the space of the contemporary. I’m so excited that your encounter with the cycle literally enacted this swerve! What happened?

VIEIRA: I first saw Fifty Days shortly after finishing undergrad, around 2001 or 2002. I had a studio, but the work wasn’t going anywhere. I was working in this very end result-driven way, and I felt hampered by my theory-heavy education. But when I saw the Twomblys, I was dumbstruck. I suddenly felt like it was okay to do something deeply uncool and explore my latent interests in history, in deep time, in antiquity, that I didn’t feel I had permission to explore in the milieu I had just left. It was a watershed moment for me. There’s literally a before and after.

HOLMES: Wow, yes—that kind of transformation of practice is exactly why I’ve found it so productive to be in conversation with artists and curators in my own work on antiquity. It’s why I found it exciting, and challenging, to take on an exhibition project. I’m not a curator. I’m not a museum person. I’m not an art historian. Yet, I realized if you want to do public-facing work as someone who works on classical antiquity, then the museum is crucial. Museums are major sites for the negotiation of value. They can reproduce the worst kind of timeless classicism. You can put a lot of history on the wall labels, but you’ve still got the pedestal, you’ve still got the beautiful body, and—

VIEIRA: Right! I was floored to read in Johanna Hanink’s The Classical Debt (2017) of someone’s early negative reaction to seeing archaic korai: “Won’t someone rid me of these Chinese girls!” Clearly they were not the “beautiful bodies” this fellow was looking for in antiquity.

HOLMES: Yes, the history of classicism over the last couple hundred years in the United States and Europe is pretty much the history of a valuation that’s deeply affected by myths of whiteness, about ancestry, cultural hierarchies, and racial purity. We desperately need a new wave of critique and a close examination of the history of classicism. At the same time, so many artists— you’re a great example of this, and there are many others—are creatively and incisively engaging with “classical” antiquity in ways that we don’t have a critical vocabulary for.

We have to pay attention to these multiple forms of engagement. The relation with the “classical” past is going to be different if I talk to you, or another classicist, or a Sanskritist, or my five-year-old son. We all participate in multiple overlapping communities of care, but we’re not all caring for the same thing. We value the ancient past in different ways; each of these acts of valuing constitutes a different “we.” Concepts can help us to be critical with respect to damaging forms of valuing classical antiquity. They can also sustain new communities, a new “being with,” as Donna Haraway would say.1

Liquid Antiquity: Conversations (interview with Matthew Barney), installation view, commissioned by the DESTE Foundation for Contemporary Art and designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Benaki Museum, Athens, April 4–September 17, 2017. © Diller Scofidio + Renfro. Photo: Matthew Johnson.

VIEIRA: Yeah. I didn’t want to approach this craft, this site, from the past. I wanted to engage directly with the actual people, with what is happening there right now. History is fascinating, but so is how we are managing its legacies today. Who are the people rebuilding this object, these modern people with modern problems? And what is their relationship to it?

HOLMES: Right, and their relationships to one another. I love how your book is simultaneously interested in their “we,” as it exists now, and at the same time it’s oriented toward this transhistorical “we” created by craft knowledge and re-instantiated in the book, which looks forward to a new “we.” The carvers are all different, with very particular voices and perspectives. But somehow their techniques surface in the text, with fifteen different people trying to put into language their embodied knowledge. What they say starts to overlap—and you get a trace of this shared technique. In an important way, this shared technique reflects a certain shared way of valuing an ancient past. The book seems to me to be about this particular, shared valuation: something that’s embodied and also impossible to confine to the boundaries of a single body.

VIEIRA: Thanks for recognizing that. I was hoping to reflect the conversational way in which master/apprentice learning is traditionally communicated. I had no interest in creating a marble-carving manual, and it should not—cannot—function as one.

HOLMES: Yes, and that comes back to the question of what a book, or writing, can do. I think a lot about the forms in which conversations or concepts can acquire a material trace so they produce different kinds of communities. I’m interested in a critical vocabulary that doesn’t force this new, transdisciplinary work about “the ancients” into old dichotomies. But at another level, I see conversation as not only criticism. We’re making something new together, a new object.

VIEIRA: Absolutely. There’s a “we” in here.

Brooke Holmes teaches at Princeton as a comparatist and classicist and directs the Interdisciplinary Doctoral Program in the Humanities (IHUM). Her project Liquid Antiquity (2017), with the DESTE Foundation for Contemporary Art, comprised a multi-authored book and video installation designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro and has been exhibited in Athens and London. She’s currently finishing a book entitled The Tissue of the World: Sympathy, Life, and Nature in Greco-Roman Antiquity.

Artist Allyson Vieira lives and works in New York. She has exhibited extensively both internationally and in the United States, and her first major catalog, Allyson Vieira: The Plural Present, was published by Karma Books in 2016. She is currently Assistant Professor of Foundations at the Corcoran School of Art at the George Washington University in Washington, DC. On the Rock: The Acropolis Interviews was published by Soberscove Press in 2019.