This is America, you live in it, you let it happen. Let it unfurl.

—Thomas Pynchon, The Crying of Lot 49

On May 18, 2011, the United States Marshals put the personal effects of Ted Kaczynski up for auction. Among the souvenirs were simple tools (a handsaw, a fishing rod reel and handle, some fluorescent hunting arrows); a pair of shoes fitted with the soles of a smaller pair to confuse the police; several pairs of dark sunglasses; and the Unabomber’s private journals. The auction raised $232,246; the journals alone fetched $40,676. Someone paid $20,025 for the hooded sweatshirt and black aviators made famous by the sketch on Kaczynski’s FBI wanted poster. The handwritten manuscript of the so-called Unabomber Manifesto, or what its author titled “Industrial Society and Its Future,” fetched $20,053—nearly as much as the typewriter it was typed on: $22,003.1

The US Marshals’ press release doesn’t mention the identities of the buyers—who, mused one appraiser, are probably a weird bunch in their own way. We do know one of them, however: the Danish artist Danh Vo. In a bay on the fifth floor of the Guggenheim Museum’s ramp sits a typewriter in its open case—a work titled Theodore Kaczynski’s Smith Corona Portable Typewriter (2011). The machine is one of over a hundred objects collected in Vo’s mid-career retrospective, Take My Breath Away. Collected is the word for it: the ramp is strewn with everything from medieval Catholic statuary to Robert McNamara’s furniture, crystal chandeliers to photogravures, and ink pens handled by JFK to letters signed by Henry Kissinger. Vo favors objects that were in proximity to men and events that shaped the twentieth century. Vietnam, where Vo was born, figures both as the site of bloody trials for early French missionaries and an American-made quagmire— the word in one hand, the sword in the other, the cross over all. His collection, and his retrospective, figure the twin diasporas of the Republic of Vietnam and New Deal America.

Danh Vo, She was more like a beauty queen from a movie scene, 2009. Mixed media, 38 x 21 1⁄2 in. Collection Chantal Crousel. © Danh Vo. Photo: Jean-Daniel Pellen, Paris.

It would be easy to dismiss Vo’s practice as that of a deep-pocketed amateur historian—to put “art” in scare quotes. He certainly does buy things, but in doing so, Vo makes auctions part of his process. The auction form itself goes on display, and with it the cultural valuations it registers at a certain point in time. In an auction, the purchase isn’t guaranteed; in the exhibition, the self-evident gravity of an object isn’t, either. Vo’s investment in Kaczynski’s typewriter, for example, piles a dry ambivalence onto the scale against a cleaner and more flattering version of American history in which evil finally gets its due. (“There are many like it but this one is Kaczynski’s.”) Vo gives to Kaczynski an emphasis and a seriousness that goes beyond weirdness, and beyond a macabre fascination with a serial terrorist. Throughout Take My Breath Away is the double valence of possession: to own and to be owned (obsessed) by.

Vo often deconstructs his purchases, or preserves them intact. She was more like a beauty queen from a movie scene (2009)—a bugle, drum sticks, fife, bayonet sheath and sword belt, a field radio, and other military items, all attached to an American flag with thirteen stars on the canton—is unique for being restored to an ideal state. The piece’s composition mimics that of the lot as depicted in an auction catalog, which is just as well: this is not the equipment of a single US soldier, but a synecdoche for the American myth—a Frankenstein’s monster of a soldiers’ kit, pictured in the process of being honored in the twenty-first century—honored by its sale. The flag, mounted on the wall and studded with old-timey instruments, makes a bellicose parody of its idealism.

Vo’s work doesn’t treat power in the abstract so much as the ways that we, on average, come up against powerful frameworks. He is interested in feeling out the legal parameters of the nation-state more than in transgressing them. For an untitled series of sculptures, made in 2008 and 2009, Vo sawed down medieval statuary to the size of regulation carry-on baggage, and displayed the pieces in unzipped suitcases. One of his earliest works, Vo Rosasco Rasmussen (2003), is represented at the Guggenheim by four Danish legal documents—for one marriage, one civil partnership, one divorce, and one dissolution. A wall label explains that the artist legally married and then quickly divorced two friends, adding their last names to his own in the process. Both pieces delineate how absurd an act can be while remaining completely within the form of the law.

Vo Rosasco Rasmussen appends a kind of legal provenance to the artist’s family name, not unlike the Americanization of European immigrants at Ellis Island. This same worldly sort of law determines the provenance of Vo’s many found sculptures. The auction is preceded by another ritual: research into the history of the objects on offer, in order to verify their authenticity. The authority of Vo’s work depends on such attribution—for instance, the journey of a carved ivory tusk (Lot 12. A Vietnamese Carved Ivory Tusk, 2013) can be traced from Vietnam to the White House to the Guggenheim. Vo has also encoded his own family history in his artworks: Oma Totem (2009) is a stack of objects his grandmother received from a German relief group after immigrating there in the 1970s. A television sits on a mini fridge that sits on a washing machine; nailed to the fridge is a wooden crucifix. This, too, is a valuation—of what the German state and German NGOs thought would help a new immigrant assimilate into their culture. Denmark and Germany recognize their citizens’ legitimacy the way Sotheby’s recognizes that a print by Ansel Adams was once owned by Robert McNamara. Granted a respectable provenance, Vo and his sculptures are not simply allegories, imitations, or representations; they are also examples.

Danh Vo: Take My Breath Away, installation view, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, February 9–May 9, 2018. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2018. Photo: David Heald.

In this regard, Vo’s and his patrons’ pockets are deep enough to achieve a kind of (capitalist) realism. Lining the Guggenheim’s ramp as it spirals upward, as if to the apex of culture, are lighting fixtures, ink pens, and office furniture fit for heads of state. A trio of works comprising vintage chandeliers, variously treated, once hung above the conference tables at the Hôtel Majestic (then the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs) as the 1973 Paris Peace Accords were signed, putting an end to American aggression in Vietnam. Here they are literally brought low—stripped of their physical and historical distance. Behind a scrim, in one of the ramp’s bays, Vo spreads out a chandelier’s arms like ribs. One hangs in the visitors’ path from a heavy-gauge chain. Another is still suspended in its packing crate, with the face removed; the crate is marked Centre Pompidou. As for its continuing provenance: the chandelier works are in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the Statens Museum for Kunst, and the Centre Pompidou, respectively. Although money, or money’s power, is part of Vo’s method, it’s facetious to say the work is about its prices.2 True, his dozens of variously titled works made by gilding cardboard boxes routinely fetch six figures at auction, travelling the world like the commodities they used to hold. But other pieces draw on the authority of being owned by museums. Hi-fi and high-maintenance works like the chandeliers marry the priorities of one institution with those of another.

Danh Vo: Take My Breath Away, installation view, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, February 9–May 9, 2018. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2018. Photo: David Heald.

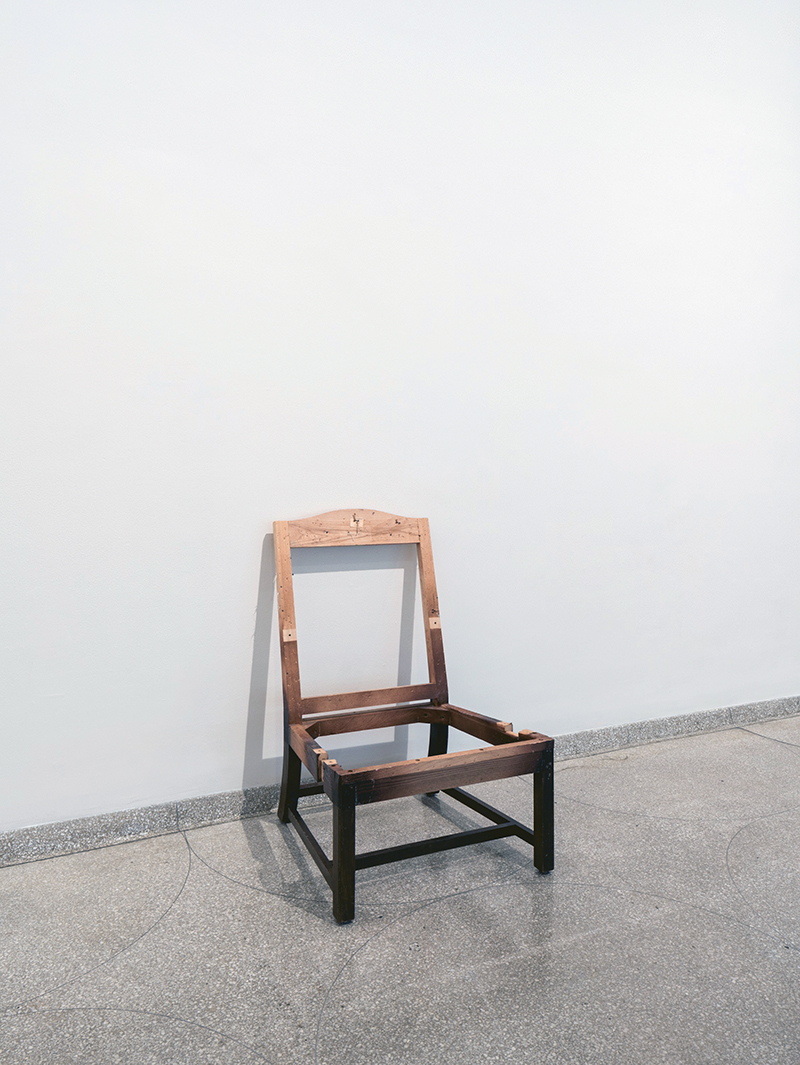

Where provenance is concerned, Vo’s works almost always depend on wall labels and other paratext: The McNamara pieces, for example, are titled with the lot number given by Sotheby’s at the original auction; a wall text further explains their origins. The labels manifest a museological version of the “administrative sublime” of the auctions from which Vo sources many of his objects.3 The nine pieces, titled Lot 20. Two Kennedy Administration Cabinet Chairs (2013), came from JFK’s cabinet room and were a gift to McNamara from the widowed Jaqueline Kennedy; now they are owned by museums, foundations, and individuals. The chairs have been flayed and dissected, by a thousand cuts, and their parts arranged in bays throughout the exhibition. A pile of horsehair padding rests on a low platform; a pile of sawed-off wooden arms bunch against a wall; green leather cascades down from a nail. Each piece stands in for the whole as well as its deconstruction; each whole wants a larger whole. Vo’s symbolism follows an almost administrative procedure. Horse Hair suggests Chair, Chair suggests Kennedy’s Cabinet, Cabinet suggests the United States, and the United States suggests the Vietnam War. McNamara was known as a ruthless statistician. Vo paid $146,500 for the two chairs.

If Take My Breath Away adopts a certain bureaucratic sense of progress, it resists another procedure: Vo declines to use the Guggenheim ramp as a chronological structure. The exhibition design doesn’t build up or out so much as in. As you move along the ramp, in either direction, series repeat themselves; the show increases in density but not in years. There are gilt cardboard boxes, Talavera pots, and statues in suitcases throughout, like a sprinkling of his most irresistible collector bait; bits of Lot 20. are spread across three floors. Coupled with Vo’s characteristically spare installations, the objects feel padded not just by physical space but by their temporal relationships. What seems like disorder on a small scale—a difference of six years between two adjacent Vo pieces, plus the hundreds of years’ difference in the origins of the components—congeals into the fifteen-year timespan of the exhibition.

Danh Vo: Take My Breath Away, installation view, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, February 9–May 9, 2018. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2018. Photo: David Heald.

There is, however, one particular timeline: a series of fourteen letters from Henry Kissinger to theater critic Leonard Lyons (and in one case, to his wife, Sylvia Lyons). These are displayed in sequence, right to left (or up the ramp); the letters provide a miniature chronology of the war in Vietnam. “I warn you, I’m insatiable,” he writes in 1969, thanking Lyons for a night of ballet. By 1970, Kissinger finds himself too busy to accept. He excuses himself with a euphemism: “I would choose your ballets over contemplation of Cambodia any day—if only I were given the choice.” But, “Keep tempting me; one day perhaps I will succumb.” Kaczynski read Thoreau, Kissinger saw Hello Dolly!, and, like other forms of culture, an art exhibition is a profoundly indifferent structure. Within this structure, though, appear the artist’s valuations—submitted for our “contemplation” as a set of carefully selected facts.

Danh Vo: Take My Breath Away, installation view, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, February 9–May 9, 2018. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2018. Photo: David Heald.

Vo paid $16,250 for Lot 65. (Kennedy, John F., Thirty-fifth President) (2013)—a line drawing of a sailboat rendered in brass, which Vo has stripped from its wooden base and hung upside down as a wall work. “On the day of the assassination,” reads the corresponding entry in the Sotheby’s catalog, “it has been said that hotel workers cleaning the President’s suite found a doodle of a simple little sailboat on hotel stationery near Kennedy’s bedstead. The sculpture of the Victura was a gift to McNamara from Senator Edward M. Kennedy and his then-wife Joan.”4 Senator Kennedy and his wife have framed Victura as John F. Kennedy’s Rosebud—a guileless symbol of his purest desires. Inverting it, Vo has made the boat a distress signal, a snow globe falling from the President’s hand.

Some of the tautest structural moments in Vo’s retrospective occur where the artist has appropriated or readymade objects already considered to be art. Among McNamara’s effects was a framed Ansel Adams photograph; Vo bought it at auction for $53,125. The print is hung in the Guggenheim with little comment, aside from the title: Lot 89. Adams, Ansel (2013). Here Vo’s light touch leaves an uncomfortable silence, and questions rush in to fill it. Why did McNamara own this print? Was it a gift? Did something in it speak to him? (Was the snow tumbling through Yosemite a grayscale vision of napalm consuming the jungle?) For Vo’s part, why did he choose this photograph over McNamara’s other artworks: prints by Joan Miró and Pablo Picasso; two original abstract oil paintings by Manabu Mabe? None of these fetched half as much as Vo spent on the Adams. Then again, only McNamara’s Adams of Yosemite is an American icon photographed by an American icon and once owned by an American icon.

Danh Vo: Take My Breath Away, installation view, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, February 9–May 9, 2018. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2018. Photo: David Heald.

What Vo leverages most effectively is the difference between what an artwork stands for and what an artwork is used for. His We the People consists of a full-scale copper replica of the Statue of Liberty, kept as some 300 unassembled sections. The artist usually exhibits a few, never all, of the segments together. Among the seven parts on display at the Guggenheim are three pieces of the statue’s left hand—exploded into back, palm, and thumb—the hand that would hold the tablet inscribed with the date of the Declaration of Independence: “July IV.” Vo’s statue is ostensibly the same size and shape as the one installed on Liberty Island. The construction, too, is similar: both comprise thin copper skins, approximately 2.4mm thick, hammered over metal scaffolding. Among their differences—indicative of the gap between 2011 and 1886—is the fact that Vo’s was made in Shanghai, while New York’s was made in Paris.

As much information as Vo gives, Take My Breath Away leans on what is not there; what the artist withholds and what his subjects withhold. There are several works for which there is no background beyond a title, date, and owner; the work poses as a self-evident object. Set aside purchase power and sheer historicity; the contrast between known and unknown is what animates the exhibition. One requires the other. Lot 100. Six Small Middle Eastern Antiquities (2013), like the pinioned flag in She was more like a beauty queen, puts the artifacts second to the way they are displayed. The piece consists of the velvet tray these six “Middle Eastern Antiquities” were stored in; the objects themselves (which Sotheby’s describes as, “A group of Canaanite antiquities, circa mid-2nd millennium B.C., comprising a bronze dagger blade, two small pottery jars each of globular form, a pottery oil lamp with trefoil lip, and the upper part of a mold-made terracotta figure of a goddess holding her breasts”) 5 are absent; what remains are their empty depressions in the velvet. This is the difference between the promise of freedom and the reality of empire, between construction and deconstruction. Two untitled works from 2009 hang side by side: each is a single gold ring. The wall label is silent here. The absence of didactics is as stark as the absence of hands to wear them. As austere as the space between what you thought you were getting and what you got; what you thought you were buying and what you bought.

Travis Diehl is an editor at X-TRA. He has lived in Los Angeles since 2009.