I

It is the translucent moving image made of light and color that surrounds you and imbues the space with a kind of atmosphere that speaks to feeling.1

—Diana Thater

As I stood in one of the rooms in Diana Thater’s recent retrospective, The Sympathetic Imagination at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), looking at a video image of Monet’s garden at Giverny, I was joined by two other visitors. They were clearly delighted that, as they entered the space, they not only encountered Thater’s imagery projected on the wall but also became part of the work itself. Three projectors placed on the floor in the middle of the back wall cast video images across the room. Standing in front of them (as was inevitable) our individual shadows were multiplied threefold within the projected image before us—one tinted a pale cyan, another yellow, a third vivid magenta. Outside these silhouettes played a series of still and moving images, formed as the primary colors from the separate projectors recombined around us to produce fully colored video images of Giverny’s paths and flowerbeds.

Diana Thater, Oo Fifi, Five Days in Claude Monet’s Garden, Part 2, 1992. Installation view, Diana Thater: The Sympathetic Imagination, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, November 22, 2015–April 7, 2016. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

This appealing and visually striking moment seemed to demand a photographic record by its visitors (I had attempted it already myself), but taking a picture raised some interesting questions, especially regarding where, in relation to the spectator’s body, the experience of the installation actually happens. A regular selfie, one of my companions quickly realized as she tried to take one, did not adequately frame the way one’s shadow made a striking graphic indent in the projected image before us. On the other hand, taking a picture of the shadow itself, without the body that made it, seemed to miss something too. A further dimension was added by the discovery made by another visitor that as people passed in front of the projectors their bodies became vivid bearers of a section of Thater’s image.

Such “literalism,” in Michael Fried’s term—that is to say, the theatrical way the spectator is made to attend to the presence of her or his own body—is potentially at odds with Thater’s broader aim of absorbing the viewer emotionally in the imagery she presents.2 An important question about her work, therefore, is to what extent it has the capacity to move one’s attention between these positions, to use the viewer’s bodily awareness as a means to access the content of the imagery. In some works, Delphine (1999) for example, the shift is effortlessly achieved. Shot almost entirely underwater, Delphine shows an encounter between Thater’s film crew and a pod of dolphins in the Caribbean. The spectator, earthbound meanwhile, watches the humans in the film clad in scuba gear, as they swim with the dolphins, all traversing a quite different space from ours. While the viewer navigates the gallery space horizontally, the dolphins’ world extends in all directions, sometimes laterally, often vertically, toward the sun—a body with its own distinctly cosmic spatial trajectory. The placement of the projectors in Delphine, suspended from the ceiling at different heights around the gallery, causes a kind of bodily and spatial disorientation that facilitates the viewer’s imaginative entry into the space of the film.

Diana Thater, Delphine, 1999. Installation view, Diana Thater: The Sympathetic Imagination, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, November 22, 2015–April 7, 2016. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

Not all Thater’s works function this way, however. Some remain impenetrable, albeit spectacular, formal arrangements, in front of which the body becomes the rather empty object of its own interest. A useful interpretive tool in this context is the distinction I made a moment ago between literalist presence and absorption, categories that allow us to think about the role of the viewer’s body in relation to the image, and its role in generating meaning. Thater’s corporeal emphasis is the starting point for most of her works. It is the basic condition of this exhibition—the mechanism many of the works use to prompt the viewer into an unusual awareness of the spatial dynamics around them.

In spite of the fact that these installations are shared spaces, through which many bodies move, Thater’s theatricality can result in a kind of solipsism or isolation. The way she foregrounds the viewer’s individual body sometimes reduces the meaning of the work to a contemplation of the beauty of one’s isolated presence in these lush, spectacularly color-suffused spaces. This isolation is underlined by a persistent feeling throughout the exhibition that spectators are caught in the midst of something forcefully projected into a space, their bodies exposed as in an enfilade. This last term serves well, since it implies not only the precision of a military maneuver (it describes a formation’s exposure to enemy fire along its flank) but also a line of sight from a specific position (that of the shooter), threaded across a space toward his or her object. The idea of the projections in these installations as intersecting arrays of sightlines powerfully evokes the feeling of exposure that Thater’s works generate. It speaks of the power of the gaze.

In a work such as China (1995), then, in which the viewer is encircled by six projectors casting imagery that wraps completely around the room, the feeling of confinement is acute. In this case, though, the bodily feeling generated by Thater’s literalist use of space is used to inflect the subject matter of the film, which shows two performing wolves whose trainers attempt to make them stand still (mostly unsuccessfully in the case of the eponymous wolf, China) in the middle of a circle of six cameras used to shoot the footage. The correspondence between the viewer’s position surrounded by projectors and that of the wolves—social creatures, like ourselves—before the watching video cameras is disconcerting enough, but the power of the work lies in the way it insinuates the authoritarian power of discipline and control, the dynamics of the individual within society before the coercive power of the gaze.

Diana Thater, China, 1995. Installation view, Diana Thater: The Sympathetic Imagination, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, November 22, 205–April 7, 2016. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

II

Animals are born, are sentient and are mortal. In these things they resemble man. In…their habits, in their time, in their physical capacities, they differ from man. They are both like and unlike.3

—John Berger

One way out of the isolation we sometimes encounter in the exhibition is through emotional engagement with the animals Thater’s works often show. As the artist herself explains, this encounter is conceived in terms of the question posed by works such as A Cast of Falcons (2008), which features the image of various birds of prey, one of which looks directly back at us. “What do I see when I look at the other and what does it see when it looks back at me?”4 Thater’s affinity for the animal kingdom sent me back, ultimately, to John Berger’s similarly impassioned meditation on the subject, “Why Look at Animals?” Berger’s typically polemical, humane, Benjamin-inflected essay, published in 1980, asks us, as Thater does, to consider the relation between people and animals as the interface of a series of signs. For Berger, the roles we assign animals in the modern world—as pets, as exhibits in zoos, as commoditized body parts—signal not only our estrangement from them but also human alienation under industrial capitalism in general. Animals had once been central to our lives, as “food, work, transport, clothing,” but are now marginalized by our new habits of life and habits of mind; our relationship is profoundly impoverished as a result.5

Diana Thater, A Cast of Falcons, 2008. Installation view, Diana Thater: The Sympathetic Imagination, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, November 22, 205–April 7, 2016. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

Originally, though, animals had a mythic function, according to Berger, a magical as well as a utilitarian meaning. Since we lived with them and parallel to them, humans and animals were joined in what Berger calls an “unspeakable companionship,” its unutterability an indication of its authenticity. 6 Animals’ original proximity to us in this sense, Berger argues, has important metaphysical consequences. Firstly, by presenting a contrast to us, animals acted as a stimulus to inquire more deeply into human nature and its relation to the surrounding world. Animals’ proximity thus provoked “some of our first questions” and offered answers to them.7 Subsequently, though, as the primordial bond between people and animals deteriorated, as our increasing linguistic and social sophistication unbalanced the relationship, they became a cipher. Animals’ original state eroded to the extent that they no longer served any function outside the service of human needs, their meaning reduced merely to that of an empty anthropomorphic sign. The question Berger postulates, then, is whether it is even possible any more to look sympathetically at animals and have any real understanding of them. Given the pervasive nature of capitalism since the nineteenth century—when we finally split from the traditions that mediated between man and nature—Berger’s answer seems to be a resounding no. For him, all we can now do by looking at animals is see the consequences of that rupture.

Diana Thater, A Cast of Falcons, 2008. Installation view, Diana Thater: The Sympathetic Imagination, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, November 22, 2015–April 7, 2016. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen

The melancholy undercurrent of Thater’s animal-focused works suggests that, at least to some extent, she shares Berger’s conclusion concerning the alienation of our habitual relationship with the animal kingdom. One of her artistic goals, however, is to explore the possibility of depicting them in a way that reestablishes some level of understanding. In knots + surfaces (2001), Thater’s subject is honeybees, but the view of them she gives us is partial and elliptical. Four projectors rake across a large room, their images extending onto the floor and ceiling as well as the walls and an architectural pillar; they show four huge, colored hexagons, like a multi-colored honeycomb, over which the figures of bees swarm and quiver. Some of the bees are large and crawl across the colored shapes, while others are silhouetted in flight, their frenetic movement making it difficult to follow individual forms for more than a fraction of a second before they are lost from view.

Cumulatively, the viewer becomes aware of these animals not as individuals but as an aggregate. We sense the structure or pattern to their movements, even if its precise meaning is unknown to us. But although the bees operate at a wavelength to which the human spectator is not attuned, Thater encourages us to regard our knowledge of them in terms of the feeling of bodily difference. She characterizes this approach as “knowing being itself through the body…—feeling dolphins, feeling bees.”8 When most effective, Thater’s works use the knowledge of one’s own body gained in the installation space to speak to a feeling of difference—spatial or temporal—generated in the imagery she presents, not in a straightforwardly anthropomorphic way, but by allowing us to see the shape of that difference.

Diana Thater, knots + surfaces, 2001. Installation view, Diana Thater: The Sympathetic Imagination, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, November 22, 2015–April 7, 2016. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen

III

The rhizome itself assumes very diverse forms, from ramified surface extension in all directions to concretion into bulbs and tubers.9

—Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari

The form of the retrospective exhibition suits Thater’s work well since it allows her the opportunity to present old and new works as part of a continuum of ideas that the viewer experiences as a set of shifting perspectives. Such continuity is given a paradoxical edge by the fact that the show is scattered in sections across the LACMA campus. This gives the exhibition a rhizomatic structure, the roots of which run throughout the museum, emerging in new forms in different spaces. Within each section, The Sympathetic Imagination makes no attempt to keep the works it contains separate from one another. Instead, images from one room escape through doors or openings into adjoining rooms; fragments of videos form partial images in distant spaces; the pink ambient glow of one installation bleeds into those around it. It is interesting, therefore, that the term enfilade, which I applied to Thater’s work earlier, also has an architectural sense—it means the way a suite of rooms can be organized so that all the doorways line up throughout, the apartment threaded through by a continuous sightline (the term derives from the French, meaning to thread, like beads onto a string).

Diana Thater: The Sympathetic Imagination. Installation view, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, November 22, 2015–April 7, 2016. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

The open-endedness of Thater’s work allows individual visitors to move through these spaces unfolding their own meanings as they go. This strategy owes much to the idea of Gilles Deleuze, whose seminal A Thousand Plateaus, written in collaboration with Félix Guattari, examines many of the themes with which Thater is concerned. Aside from the central role animals play in the ideas of this book, Thater’s approach embodies Deleuze and Guattari’s conception of the profound instability of subjectivity, the idea that existence can only be grasped as a phenomenon constantly in motion, formed out of a shifting set of relations on an infinite plane; thought arises out of this “immanence,” as Deleuze calls it.

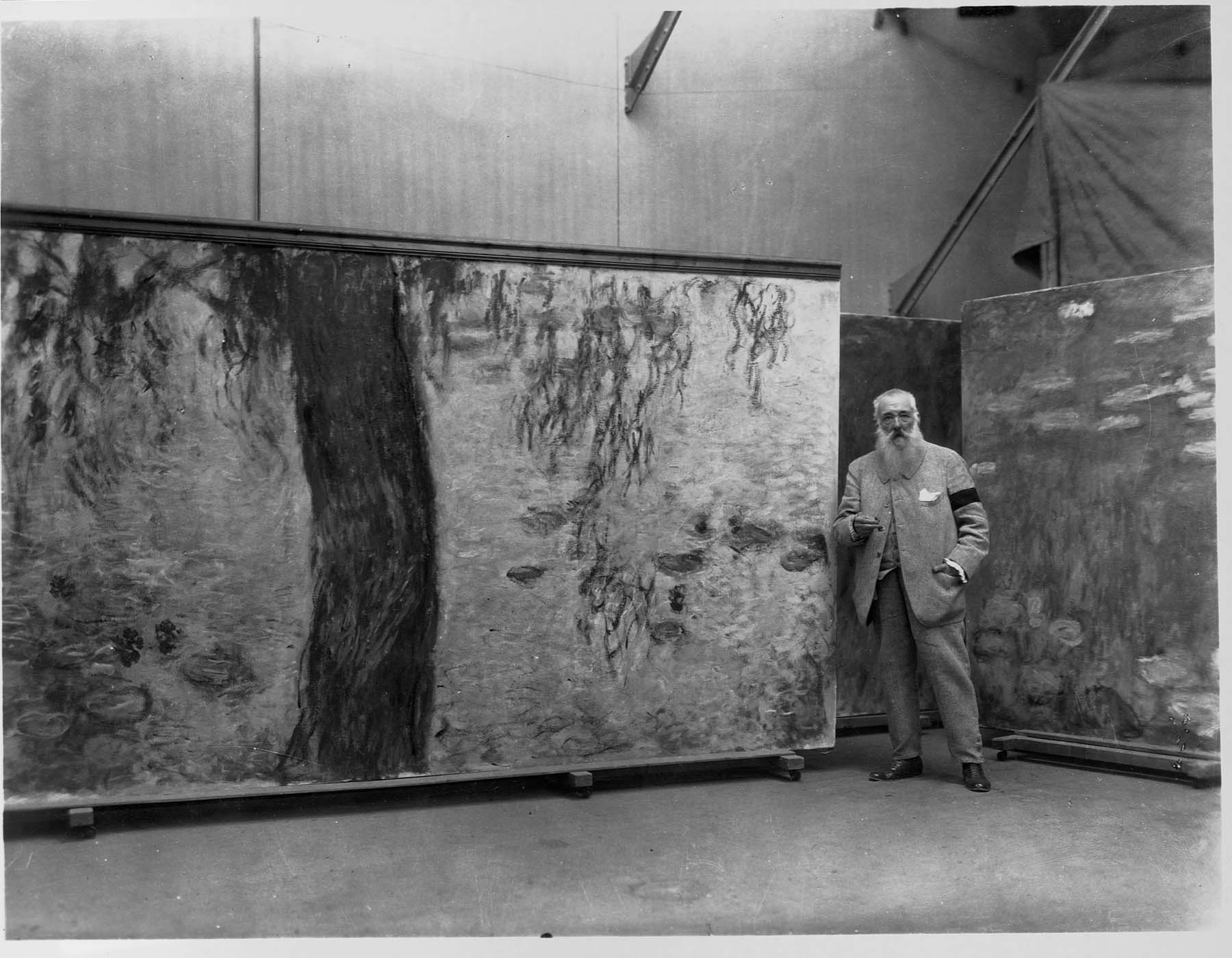

The idea that meaning is immanent to any moment, and organizes itself out of the varying relations it encounters, is especially attractive from a personal perspective, not least because it allows me to collapse the otherwise conflicting roles I have in relation to Thater’s work, as both art historian and critic, bringing them both together in a contemporary moment of interpretation. In order to do this, then, let us return to Monet’s garden at Giverny, where I began my account with a description of Thater’s video installation Oo Fifi, Five Days in Claude Monet’s Garden, Parts 1 and 2 (1992). This garden is the location of a significant moment in Monet’s career (one that has enormous resonance for Thater’s project), a moment when corporeality before the image reemerged as a central concern of his painting. This bodily emphasis, which Thater takes for granted, was anathema to Monet during a career mostly occupied with optical concerns. Late in life, however, Monet conceived a program of monumental water lily paintings called the Grandes Décorations—vast, immersive canvases, which were to be housed in their own dedicated architectural setting, wrapping around its interior walls. This context arguably reshaped the relation of Monet’s work to the corporeal presence of the spectator.

Claude Money with Nymphéas, n.d. Image courtesy Underwood & Underwood/Library of Congress/Cobis/VCG via Getty Images.

Monet’s Grandes Décorations, it should be noted, although envisaged in the last decade of the nineteenth-century, were not executed in their enormous final form until much later, amidst the national and personal traumas of the 1910s. In 1914, his eldest son Jean had died, only three years after the death of Monet’s long time companion Alice Hoschedé. He had barely painted since. The outbreak of war only deepened his sorrow: “Yesterday I resumed work,” Monet wrote in a letter on December 1, 1914. “It’s the best way to avoid thinking too much about the sadness of the present. All the same, I feel ashamed to think about my little investigations into form and color while so many people are suffering and dying for us.”10 During the war itself Monet’s garden had not been isolated from the battlefields, which were only 50 kilometers distant. The sound of artillery explosions frequently disturbed the peace of the garden, and on several occasions, as a German invasion seemed imminent, the painter was forced to contemplate fleeing Giverny altogether. When the armistice was finally signed four years later, Monet wrote to the Prime Minister Clemenceau, an old friend of his from the 1860s, offering some of the works he had produced to the French state as a celebration of the end of the conflict. On one hand, then, as I stand inside and before Oo Fifi, Five Days in Claude Monet’s Garden, I have in mind Monet, the grand old man at the end of his career, making his stately, unifying gesture of mourning and celebration to France. On the other, I am aware of Thater as the author of this work, at the beginning of her career, a neophyte still in search of an audience, putting together Oo Fifi for her first major show.

One of the consequences of this temporal openness in Thater’s work, her tendency to retreat from any specific context to a generalized examination of a set of relational positions (body before a gaze, animal next to human, individual in relation to the cosmic), is that it fails to acknowledge the specific significance of the moment of creation, which is especially problematic in the case of Oo Fifi, which was first exhibited in August of 1992. This was a turbulent moment in the history of Los Angeles, marred by racial tension, riots, and natural disasters (an echo of the trauma that haunted Monet’s Grandes Décorations). But despite the fact that Thater’s work articulates an exposure of the body to the contingencies of its environment, and the body’s potential vulnerability in the face of larger forces—whether social, institutional, or geological—the political meaning of these ideas in this original context is allusive. Instead, Thater’s work relies on the historical awareness of individual spectators to reinsert this meaning into the work. Both the chief strength and weakness of Thater’s work, therefore, is that it allows for a multiplicity of perspectives to exist within it. Indeed, the way her show is organized, with different works contrasting vastly different scales, from the minute size of a butterfly’s wing seen in close-up to the cosmic magnitude of a rotating solar orb, all threaded together in a vertiginously disproportionate enfilade, emphasizes the contingencies of such perspectives.

The instability of meaning Thater’s work generates is absolutely at odds with the modernist ideal Michael Fried attempted to delineate in his discursive categories of literalism and absorption. For Fried, works of art possessed a transcendent state, an unvarying meaning, that could be accessed by the beholder, removing her or him in the instant of contemplation from the contingencies of their specific moment. For Thater, meanwhile, these contingencies are the basis of her work, each moment acting as the catalyst for the generation of new meanings and relations. While, on one hand, the risk of this strategy is that it sometimes produces spaces in which we are left staring only at ourselves, on the other it presents an opportunity to define ourselves from the perspective not only of other people, but through the gaze of something more radically other: animal, technology, geology, cosmos.11

Jon Leaver is Associate Professor of Art History at the University of La Verne. His research focuses on nineteenth-century art and criticism as well as the contemporary art of Los Angeles.