It’s an excessive atmosphere, but if one holds up, and the important thing above all is not to understand, the important thing is to take on the rhythm of a given man, a given writer, a given philosopher, if one holds up, all this northern fog which lands on top of us starts to dissipate, and underneath there is an amazing architecture.

—Gilles Deleuze

An exhibition unfolds like a story, or unpacks like a library. Then there is Thomas Hirschhorn. His Stand-alone (2007), reprised for the first time in the United States at The Mistake Room, hits you like a stack of books.

Thomas Hirschhorn: Stand-alone, installation view, The Mistake Room, Los Angeles, October 7–December 17, 2016. Courtesy of The Mistake Room, Los Angeles, and Coleccion Isabel y Agustin Coppel (CIAC).

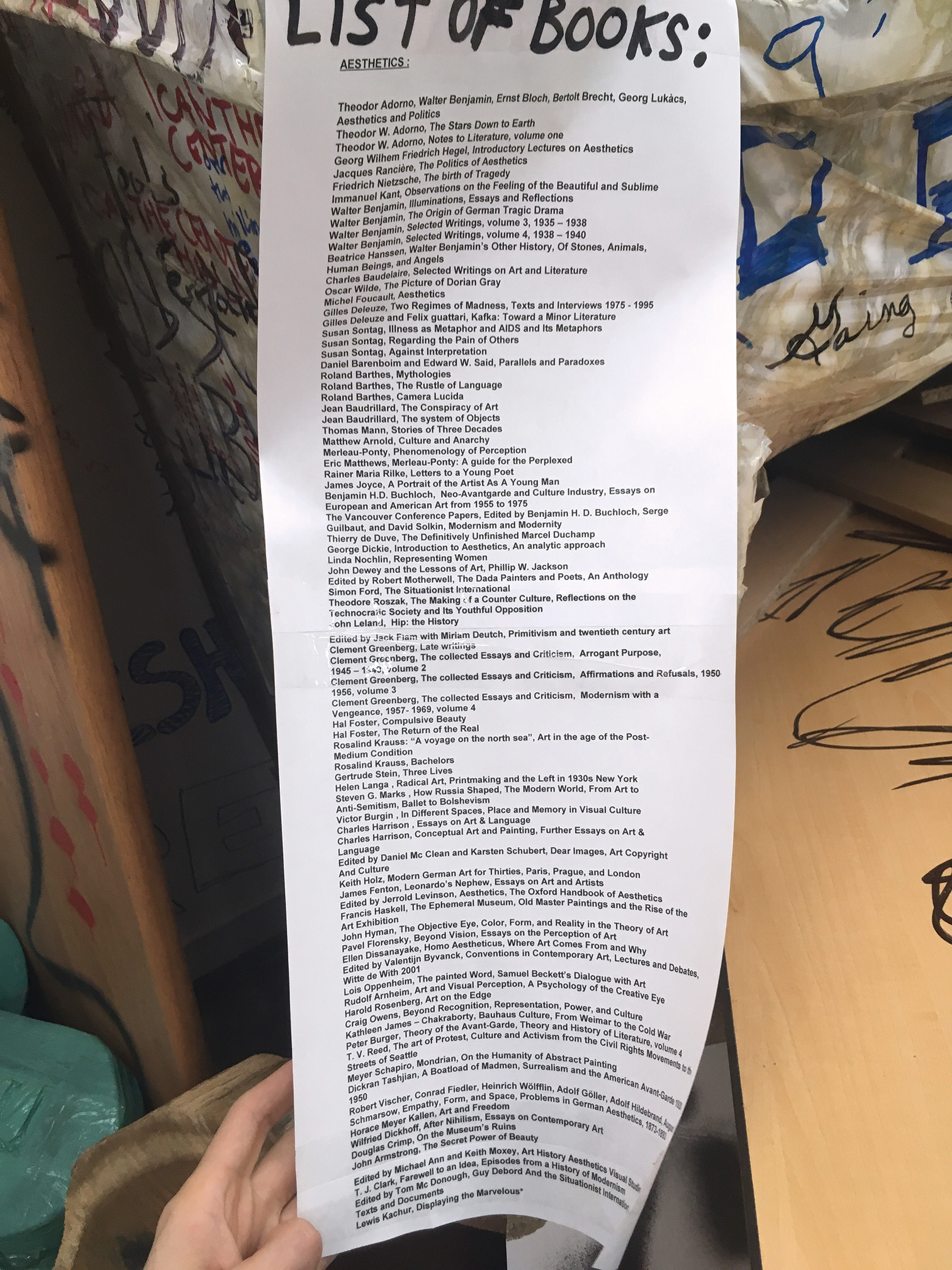

The gallery is broken into four shotgun rooms, four iterations of the same basic layout, separated by cheap, kicked-in doors. You stagger through, concussed. What you’ll notice first is a life-size tree trunk made of cardboard and packing tape that has seemingly crashed through the gallery roof and into this war zone of a living room. The delivery is as subtle as the trunk angling before you: taped to its painted-on bark are photos of blown-apart corpses, detached torsos, blood drenched clothes, caved in faces, and severed heads in the street. Looking away, walking under or around the trunk, you’ll notice the colorful graffiti covering every wall; the shelves holding a scattering of redacted leaflets of stats, lists, articles; the pile of oversized robin’s-egg blue pills stamped you; the slices of log spray-painted faith; the love seats and armchairs “upholstered” in brown packing tape, up on racks; and the CRT television sets, both taped and screwed to the wall. You’ll also notice the fireplace in each room, somewhat blocked by the tree and by the Ikea-type cardboard and particle board rubble spilling onto the hearth. Each mantel is piled ten high with books on one of four subjects (love, philosophy, aesthetics, politics). Taped to the left corner of each mantel on several joined sheets of copier paper is a printed list of the books’ authors and titles, headlined in marker: list of books.

Thomas Hirschhorn: Stand-alone, installation view, The Mistake Room, Los Angeles, October 7–December 17, 2016. Courtesy of The Mistake Room, Los Angeles, and Coleccion Isabel y Agustin Coppel (CIAC).

Across Hirschhorn’s work and in countless pieces by other artists, the stack of books can be a quick way to recruit ideas as paratext.1 The books provide a hermeneutic shortcut: the work’s valence, or at least its author’s intention, seemingly follows from the arguments the books contain. This is true of Stand-alone, yet the project depends less on its particular citations than on a recognizable humanist and post-structuralist worldview, of which the books cue the parameters. The specific titles speak to the artist’s own interests, while their hermeneutics is broad enough to be iconic in itself—of the four categories, but also of the larger project of human thought. Rather than a way out, this materiality of thought is the kernel of Hirschhorn’s practice. In their sheer numbers and cacophony, the “stack of books” in Hirschhorn becomes another of his regular materials, along with tape, cardboard, copy paper, permanent markers, televisions, and cheap lumber.

Thomas Hirschhorn: Stand-alone, installation view, The Mistake Room, Los Angeles, October 7–December 17, 2016. Courtesy of The Mistake Room, Los Angeles, and Coleccion Isabel y Agustin Coppel (CIAC).

You can’t read these books, though—or, to the point, you won’t do so here—and not just because we are conditioned to not “touch the art,” in even a ransacked white cube. This much is underscored by an installation that surrounds, closes in, and gives no space for action. The mantels sit near 60 inches high, putting the book stacks at the standard eye level of artworks. The stacks are not ordered as in a library but rather skewed with an aesthetic, intentional casualness; to disturb the piles would undo the composition. The books are crisp, not “well-thumbed volumes” but bubble-mailer fresh. They retain a sealed quality, as if not so much texts as illustrations of texts. They sit on the mantelpiece like the leather-bound trophies of darker ages, where just the fact of a book in the home besides the Bible spoke to uncommon learning.

The stack of books is potential—measured in number of titles, pages, words, but also in terms of the time investment required to read them: a kinetic time. The library contains hours of reading. Yet the only chairs line the walls on metal racks, off balance, more or less in storage. Chances are you will not spend hours standing in a gallery to read a dense philosophical tract. Stand-alone is a gauntlet and a confrontation. Hirschhorn frames up your busy life with the contrarieties of touching and not-touching, reading and not-reading, knowing and not-knowing—the guilt of unacquired ideas.2

Nor should “stack” or “list” here imply a sequence. Like the apprehension of a history painting, Hirschhorn’s titles are dumped on you by the hundreds in an instant. The stacks of books constitute a tumbledown syllabus, a sculptural version of the list of books taped below (and not the other way around). Works by Luce Irigaray, Michel Foucault, and Marquis De Sade follow Seneca, Virgil, and Euripedes, all under the heading love; you are in chaos, and the books are too.

Maybe you’ve read a few. There is no way you’ve read them all. Hirschhorn hasn’t. “I’ve heard people making critical comments about your work,” says Alison Gingeras, interviewing Hirschhorn, “along the lines of, ‘Thomas has not read all the works of Deleuze or Bataille.’” To which Hirschhorn replies, “Of course I haven’t!” Instead of an expert, Hirschhorn calls himself a fan. The fan, says Hirschhorn, is “committed to something without arguments; it’s a personal commitment. It’s a commitment that doesn’t require justification.”3 It’s a looser kind of love.

Thomas Hirschhorn: Stand-alone (detail), The Mistake Room, Los Angeles, October–December 17, 2016. Courtesy of The Mistake Room, Los Angeles, and Coleccion Isabel y Agustin Coppel (CIAC). Photo: Travis Diehl.

The four book-covered mantels in Stand-alone recall Hirschhorn’s quartet of monuments to his favorite philosophers. All include libraries of their texts, ranging from a small inset shelf in Spinoza Monument (1999) to a freestanding, furnished plywood room in Gramsci Monument (2013). The four thinkers occupy the spokes of a diagram Hirschhorn draws between the quadrants of his “force field”: love, philosophy, aesthetics, and politics.4 For Stand-alone, each category structures a selection of books, and each pile is topped by an oversize cardboard sculpture of a single book. Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man, Common Sense and Other Political Writings crowns politics. A Continuum Impacts edition of Jacques Derrida’s Dissemination, with a cover designed with brightly colored pills, rests atop philosophy. These categorized piles shore up certain canonical texts but also make a mess of them. They are statues, not meant to be resolved or consumed but stated with an emphatic and contagious belief.5 If Stand-alone doesn’t itself constitute a library, it points to one. Hirschhorn’s “act” was to deploy the piece—presenting and arranging four groups of texts. It is your prerogative to follow through. The action you must take isn’t inside the gallery, but beyond it.6 Meanwhile, the installation is on pause. Hirschhorn sets himself against quality—that is, expertise, virtuosity, or having read and understood his books—and for energy—the kinetic knowledge that you could gain, as he has, from even a piecemeal study of these authors.

In these wasted, unlivable living rooms, through the chaos of slogans and gore, the stacks of books slam into view like so much wood. Whereas the installation collapses and explodes, they are silent and self-assured. In the scene of death and destruction, they flee inward, into sealed contemplation. Stand-alone is not a war zone, of course, but an image of one—complete, like a training center or a TV set, with graffiti. These “slogans”—immediate, fragmentary, and aggressive—form a parallel, second text to the stacks of books. Where the stacks of books double as lists of names and titles, the Sharpie slogans read like a hash of news and ads: “fun has gone out of it,” “suicide squad,” “dead man walking,” “above and beyond,” “sticking together,” “time to accept the obvious.” There are the closed-up texts that you won’t read, the chattering text you can’t avoid, and, like trophies, the televisions, taped over and unplugged, their screens deathly gray, that nonetheless form the books’ cartoonish opposites.7 Here is the leather-bound, elitist angle: a characterization of low materials and high notions. On the mantel are the slow, reified texts; while the war porn on the tree trunk and the sanitized mayhem of television force themselves uninvited into your consideration—flashy, spectacular, and instant—to the point of oversaturation and apathy. Yet what might happen if you do seek out and apply yourself to one of these books, or many others? In Hirschhorn’s mass-media dichotomy, you might either lend your spectatorship to the cause of power or apply your efforts to a grander project (those projects of love, philosophy, aesthetics, and politics)—and thus refuse your attention to the ongoing image-war.

Thomas Hirschhorn: Stand-alone (detail), The Mistake Room, Los Angeles, October 7–December 17, 2016. Courtesy of The Mistake Room, Los Angeles, and Coleccion Isabel y Agustin Coppel (CIAC). Photo: Travis Diehl.

Hirschhorn’s installation, its cardboard and tape, is ephemeral—or, in the artist’s more precise term, “precarious”; the materials will be thrown away.8 Yet the books will persist. Even if these copies wind up in the dump, it would take much more to delete the books they represent. Unlike the news, unlike tweets or shares, unlike even online images of Hirschhorn’s work, these books are off the network. The stack of books offers a ballast—a kind of collective memory that the news cycle can’t quite wipe. Indeed, the collective project of thought does have, if not a sequence, at least a stacking effect; books accumulate, not supersede.

Art is Hirschhorn’s sphere of action, where he deploys the forces of love, philosophy, aesthetics, and politics. To the question of how to take an action that will outlive the actor—that will escape our local crises, outward into time—the stacks of books are Hirschhorn’s answer. In his image of a broken world, the falling trees and soldiers spare the books.9

Travis Diehl lives in Los Angeles. He serves on the editorial board of X-TRA.