I’m interested in the museum because it’s a place where no one expects to be misled. Whatever they give you, you believe.

–Fred Wilson 1

I can’t stand art actually. I’ve never, ever liked art, ever.–David Hammons 2

In the grey morning light of a rainy spring day, I entered the courtyard at Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles in downtown and encountered David Hammons’s vast array of colorful, vacant tents.3 Sporadically, I could make out text: “This could be u and u,” emblazoned in red at eye level. The waterproof fabrics were still wet from the morning’s downpour, giving the tents a sheen of authenticity that contrasted with their store-bought freshness. The equally shiny patrons brunching at Manuela, the gallery’s onsite restaurant, didn’t seem to have their appetites ruined by the artist’s bracing reference to the social catastrophe unfolding in our midst. Could this be us? A life in the arts in Los Angeles feels precarious at best. Rents downtown are astronomical, and local families are being displaced by boom industries, including Hollywood, tech, and the arts. In the moment, Hammons’s gesture—turning the gallery into a mausoleum for social death—invoked 36,000 unsheltered residents left to withstand an unusually chilly May day in Tinseltown.4 Any one of these tents could be waiting for those of us dependent on the patronage system that underpins the high-end culture industry. For the comfortable, another context: these tents could do a lot of people some good. Instead, we have Art.

David Hammons, installation view, Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles, May 18–August 11, 2019. © David Hammons. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen Studio.

Hammons’s tents are literal empty signifiers—Non-Sites.5 Each tent is a portal to another site with which it is metaphorically linked, each empty tent a schematic of an occupied tent somewhere else. Robert Smithson coined the term Non-Site to refer to sculptural interventions he made within white-box gallery spaces that brought in contrasting aesthetics and materials resulting from industrial exploitation and geological entropy. Each Non-Site has an inferred Site, an original, offsite location that is the source of the material and usually referenced through didactics and documentation. For Smithson, the truth that gallery goers did not want to see was the reality of asphalt-bitten New Jersey, which was too reminiscent of the bridge-and-tunnel origins many denizens sought to shed. It was the reality of their social mobility, looking back down from the peaks to which they had climbed. For Hammons, stepping back into the Los Angeles art world after decades of avoidance, the truth is that this moment is a bubble driven by a profit-led urban development model that leaves tens of thousands on the street. Meanwhile, the FBI investigates sitting Los Angeles city council members and their staffers for taking bribes from those developers.6 As a society, we sit at the top of an abyss, staring down into the possibility of collapse even as we continue to aspire to heights of affluence and progress.

Amid the tents, a rough-hewn triangle of rock is carved deep with the words “Black Lives Matter.” Votives flicker at its base. Does this funereal inscription refer to the violent economic and social exclusion that causes homelessness to affect Black Angelenos at a rate three times their share of the city’s population? Or does it address the fact that Hammons—a generation-defining political artist whose iconic 1993 work In the Hood became emblematic for the Movement for Black Lives—struggles with his status as a recognized purveyor of Black Art and Culture and his designation as a cultural authority? Rocks appear elsewhere in the exhibition, as on a settee upholstered in clear plastic with a decorative edge. Rocks represent the simplest conceptual sculptural gesture an artist can make: identifying and situating material within a lineage of art. Generally valued the most within a Western art context when they have been refashioned to resemble pliable living things, such as human bodies and plants, rocks by themselves refuse the Eurocentric imperative to faithfully represent subjects and so “elevate” materials. They become totemic.

Inside the breezeway at Hauser & Wirth, the tents have capsized. Above them, Martin Creed’s neon text blares “ EVERYTHING IS GOING TO BE ALRIGHT ” in rainbow lettering. Clearly not. Adrian Piper’s credo, “Everything will be taken away,” feels more appropriate. Piper is the only other Black artist of Hammons’s generation to command similar renown and personal controversy. Perhaps the staying power of both artists lies in their unwillingness to be standard-bearers for a racial, gendered, or otherwise identity-based politics that, in art, often functions as a kind of low-budget symbolic “reparations,” while money connected to board members at arts institutions continues to flow into new and more terrifying atrocities. Rather than refuse to participate in this circus outright, both artists court attention only to reject it publicly as a false currency.

While Piper famously “retired from being Black” on her sixty-fourth birthday, in 2012, ostensibly abdicating any perceived responsibility she may have had to hold institutions accountable for anti-blackness, Hammons continues to embrace the role of “the bad guy,” as he described to Kellie Jones in 1986, and has yet to publicly disavow it. Hammons takes this stance in opposition to respectability politics, working with the construction of Black identity through media imagery, as in a work in which he stencils “ TRIBAL ART ” onto the cover of Artforum and another that equates a photo of Tupac in a straitjacket with an image of Christo and Jeanne Claude’s drawings of wrapped bundles. Sometimes, though, Hammons’ choices ring more like Piper’s abdication, both artists’ gestures suggesting a rhetorical position of utter exhaustion.

Hammons has been called the most expensive living Black artist. Like other blue-chip artists of his generation, most of them white men, he operates with a measure of autonomy from the gallery system. He navigates by triangulating rather than being represented by a single entity, while still recognizing that the path to historicization runs through the marketplace. Hammons skewers his leading position with relish, for example, making huge paintings from found remnants of discarded tarp, which the viewer must peer under and around to observe. The surfaces are dusted with Kool-Aid, packets of which litter the gallery floor. The largest and most grandiose is labeled, in pencil on the wall, “How many of these did you make?” Beneath their veils, one can make out soaked canvases, in the manner of Sam Gilliam. Black Art, canonized by the 2017 Tate Modern, London, survey Soul of A Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963–1983, on view at The Broad concurrently with Hammons’s exhibition at Hauser & Wirth, is here remixed, becoming source material for Hammons to appropriate.7 He seems both appreciative and mistrustful of the recognition, which places him shoulder to shoulder with artists a decade senior whom he might once have looked up to. At Hauser & Wirth, a photograph, placed haphazardly in an upper corner of a wall dedicated to Hammons ephemera, declares “John Outterbridge Plaza.” A boulder crowned with kinky black hair recalls Martin Puryear’s Afrocentric minimalism, with a signature Hammons twist.

David Hammons, installation view, Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles, May 18–August 11, 2019. © David Hammons. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen Studio.

African American art and history is invoked everywhere in the Hammons exhibition. Ornette Coleman is the fugue that the show’s oblique press release riffs on in the reproduction of a booklet from the jazzman’s memorial service that stands in for an exhibition guide. Coleman’s music is a ubiquitous presence in the galleries; his colorful suits are encased in cylindrical vitrines and a host of overt and covert references to his work and the work of numerous Black artists and musicians are sprinkled throughout the exhibition. An armoire, prone on its back in gleaming cedar, is an absurd proposition aligned as much with the found-object art of Noah Purifoy as the cheeky sexual humor of Meret Oppenheim. In a photograph hung close to the floor, a wooden gle mask from West Africa floats, like Ophelia or the infant Moses, forsaken in a mass of reeds. The specter of the “junk man”—an African American archetype cited by John Outterbridge as a precursor to Black assemblage—informs Hammons’s sculptural practice. In this construction, a poor street artist, such as the emblematic Crenshaw Cowboy of Los Angeles’ West Adams neighborhood, is inheritor to a Black Art historical lineage that Hammons, in his blue-chip context, elides. Black Art history exists outside of institutions and books, held largely in personal archives, in the street, in community-based galleries like Leimert Park’s Sika piercing gallery or its former neighbor, the now-defunct Brockman Gallery, all precarious and subject to displacement by weather, rent hikes, or homeless “sweeps.” Hammons has become a symbolic marker for a larger absence within mainstream art history, his version of Black Art an unstable one made for a market that still strives to aestheticize social exclusion as authenticity. Other artists who do this include Pope.L and Nari Ward, both a generation younger than Hammons and yet to be canonized to the same degree.

David Hammons, installation view, Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles, May 18–August 11, 2019. © David Hammons. Photo: Anuradha Vikram.

Hammons has shaved and ground down wooden reliquary figures purchased in African tourist markets, some to near elimination. In his act of obliteration, Hammons prompts this viewer to ask what is art and what is an elegant hustle. Self-references abound, particularly to the artist’s notorious Bliz-aard Ball Sale (1983), which is possibly the most transparent example of contemporary art as a game of three-card monte since Marcel Duchamp’s Monte Carlo Bond (1924). A small glass bowl of water, placed on a wooden shelf like a holy font, is accompanied by a typewritten and crudely redacted missive. “Hi Carmen Annette: As much as we would love to own a snowball, not a single insurance company would cover it for us, and we called a half dozen. And, since we are not made of money like SOME people, and since we’re also paying off a home equity loan on our new kitchen, we will have to pass. But then again, if you come across any other interesting Hammons . . . ” Art investment is a shell game, less tangible than a kitchen remodel but equally status-conferring. Elsewhere, a freezer is filled not with snowballs but with shrink-wrapped copies of Elena Filipovic’s Bliz-aard Ball Sale (2017), a book-length essay on the near-apocryphal work. Filipovic’s scholarship is an act of willing this unstable art object into existence, fixing it with a permanence that the object cannot support on its own.

In Soul of A Nation, David Hammons appears not as an ephemeral trickster but as an established, historical artist. Hammons is initially represented opposite a masterful draped painting by Sam Gilliam with Bag Lady in Flight (1970s/1990), a gracefully folded accordion of brown paper bags stained with grease and marked with accents of human hair. Iconic works follow, such as Injustice Case (1970), a body print in margarine and pigment showing a Black figure bound to a chair, mounted to an American flag, and The Door (Admissions Office) (1969), in which the Black figure presses into the glass toward the space he can never enter. Flanked by politically and creatively radical artists, such as Emory Douglas and Elizabeth Catlett, Hammons is largely cast as a Los Angeles artist in the company of Charles White, Melvin Edwards, Senga Nengudi, and Betye Saar. In reality, Hammons found this context for his work in the 1970s limiting and he decamped to New York. This pivotal decision led to his ascent to subsequent market heights, even as he marked his arrival with even more dematerialized and aggressive works, such as his act of urinating on Richard Serra’s TWU (1980–81), which Dawoud Bey documented in 1981. The majority of artists in Soul of a Nation, from AfriCOBRA artists Jae and Wadsworth Jarrell to Barkley L. Hendricks and Fred Eversley, have enjoyed commercial recognition much later in life, largely in the past decade.

Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963–1983, installation view, The Broad, Los Angeles, March 23–September 1, 2019. Courtesy of The Broad. Photo: Pablo Enriquez.

If Hammons excels at making things disappear—snowballs, fetish sculptures, his own artistic persona—a counterweight can be found in Fred Wilson’s exhibition Afro Kismet & Other Works, on view at Maccarone in the Boyle Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles this past spring.8 Wilson makes unexplored Black histories visible, specifically in the Mediterranean region of Europe, where centuries of interracial cohabitation and trade have been erased by revisionist colonial narratives. In the show, created for the 2017 Istanbul Biennial as a revisiting of the artist’s 2003 American pavilion at the Venice Biennale, Wilson emulates Venetian, Turkish, and African aesthetics by turns. Enormous black glass mirrors and ornate chandeliers adorn the ceilings. Two large mosaics bearing Arabic calligraphy dominate the main space. Wilson has collaborated with master craftspeople in both Venice and Istanbul to create these objects, which are elaborately constructed but deliberately neutralized by their contextualization as graphic visual symbols, rather than as readable, language-bearing content or linear narrative.

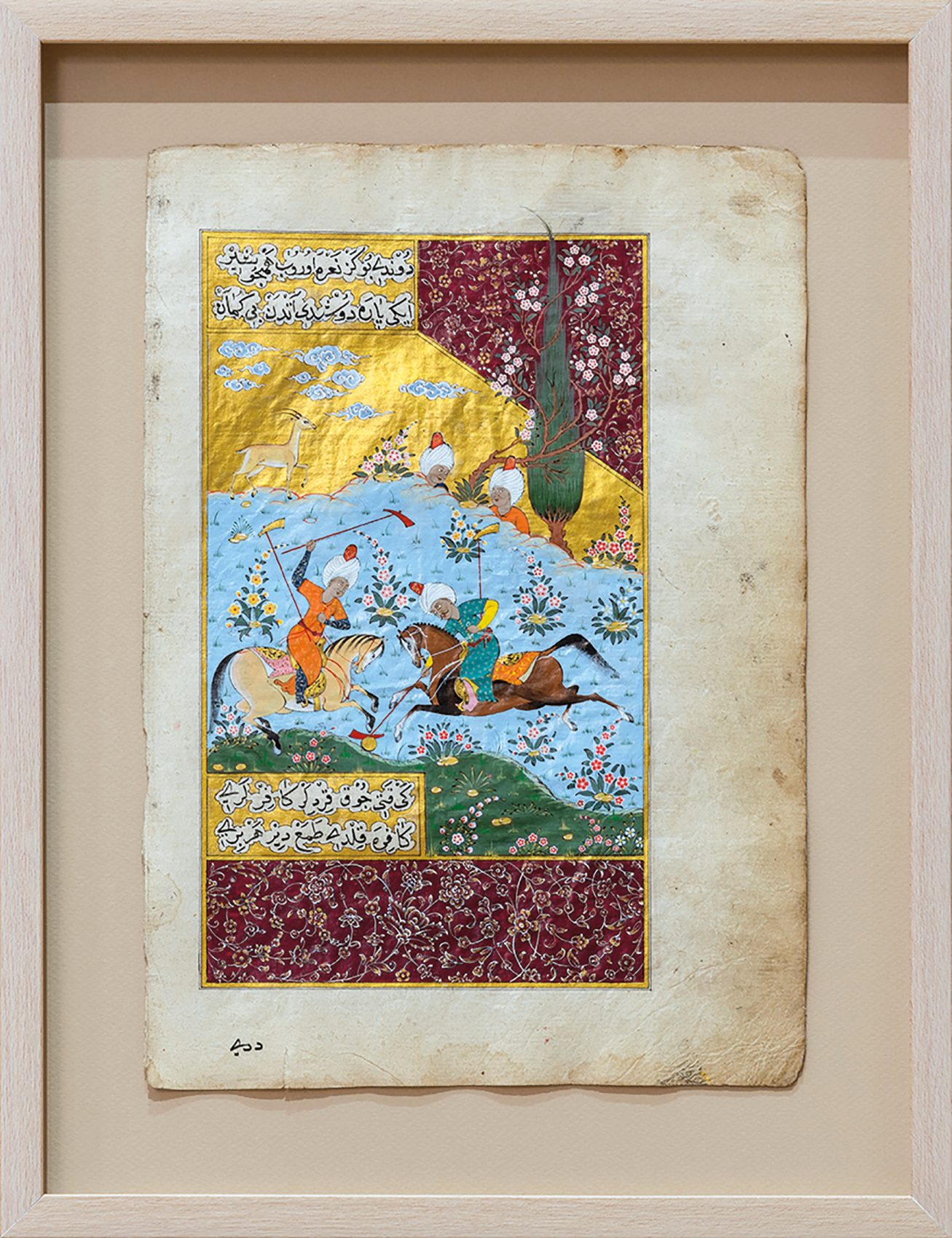

A selection of representational works in oil reminiscent of early nineteenth-century genre painting presents African diaspora characters at play in European settings. Wilson has said his goal is to illuminate the presence of Africans in European art as early as the fifteenth century. To do so, he enlisted artisan painters in Istanbul to make traditional miniature paintings featuring characters of African descent, subjects not commonly represented in the region’s art. Glassblowers and tile painters were similarly employed to create objects in the traditional style but with an Afrocentric narrative. This strategy is both visually and emotionally satisfying, reveling as the artist does in beauty and elegance. But the politics ultimately ring hollow. Contemporary Turkey is a country whose “white” racial identity was encouraged by the early twentieth-century nationalist leader Kemal Atatürk, and this designation has enabled discrimination against ethnic minorities, including Afro-Turks, Kurds, and Arabs within Turkey. Meanwhile expatriate Turks in western Europe rarely enjoy such acceptance within the white mainstream, experiencing racial profiling, harassment, and ghettoization. Wilson engages with the nearly invisible minority community of Turks of African descent, who largely descended from enslaved Africans living in the Ottoman Empire from the sixteenth century until the early twentieth century. Since then, the Afro-Turkish population has declined from nearly three million to around one hundred thousand.9 Despite this decrease, Afro-Turkish cultural rituals, such as the Dana Bayram or Calf Festival, are emerging alongside Black Turkish cultural identity, fueled by increased contact with recent immigrants from Africa, who fill in cultural gaps with contemporary traditions.

Is Fred Wilson simply blind to existing and new Afro-Turkish cultural practices, or is the methodology that he developed to confront white supremacist institutions within the American racial dichotomy mired here by misplaced expectations of universal applicability? What is the impact of an American artist, backed by art-world investment, introducing US-style racial conversations anchored in settler colonialism and chattel slavery into this political context? West African sculptures in vitrines are here, too, without labels, sometimes uncannily formed with multiple eyes or noses. It is unclear whether the sculptures’ unusual physiology originates with Wilson or with the artisan woodworkers. There is no shaving down or bewigging of these totems as per Hammons, but still very little context. “Africa” is invoked as a symbol of something other than Europe, but otherwise without geographic or political specificity. Taking the form of luxury objects, the work is organized around Black nationalist values in a way that is ripe for consumption by affluent patrons of color back in the United States.

Fred Wilson: Afro Kismet & Other Works, installation view, Maccarone Los Angeles, March 16–June 1, 2019. Courtesy of Maccarone Gallery and Pace Gallery. Photo: Coley Brown.

Wilson’s installation relies heavily on Orientalist tropes such as “blackamoors” and eunuchs that populate European colonial fantasies of Turkey. His engagement with contemporary Turks in Istanbul is lacking, in the sense that he treats them as interchangeable with any other European power rather than engaging with the specific character of the Ottoman empire’s involvement in slavery or Atatürk’s particular, racialized construction of Turkish nationalism. Wilson’s historical image of that period seems to be reflected through the lens of European academic painters of the nineteenth century, such as Jean-Léon Gérôme, whose 1866 Slave Market is an eroticized shadow theater where swarthy men sell and fondle white women in an inversion of the racial dynamics of the transatlantic slave trade. Gérôme’s role reversal helped to assuage both the sexual desire underpinning the dynamics of enslavement and the white guilt of the liberal artist class.

Istanbul, which has been a cosmopolitan city for millennia, is increasingly at odds with Turkey’s right-wing populist regime. Wilson’s critique, for all its baroque elegance, misses this reality even as its existence as an exhibition proceeds from it. If the exhibition is thereby untethered from geography, the work proposes a totalizing stance on interracial dynamics in the Western world; some would say this erasure is implicit in the “universal” as characterized above. The exhibition becomes a teaching tool for narrating psychosocial dynamics between humans, objects, reflections, and individual self-constructions in a Lacanian mode. The project visually manifests Frantz Fanon’s deconstructive psychoanalysis of Western-style racism, which positions mimesis as a survival strategy for Black people in a white supremacist system. The black mirrors in which we are reflected still bear the opulent touches of the ruling class. One has the sense that the rebels have taken the palace, but the values of monarchism remain intact.

Fred Wilson, Love is a Country He Knew Nothing About, 2018. Hassan, Arab Stallion with his Haik, 1858 by Alfred De Dreux, gilded wooden frame, Lobi figure, Bateba, pedestal, plexiglass, digital print, vinyl lettering, 98 × 81 1⁄2 × 52 1⁄2 in. Courtesy of Maccarone Gallery and Pace Gallery.

Though drawn from a body of work created for the Biennial, the present configuration of Wilson’s show originated at Pace Gallery in New York. A sense of market opportunism is compounded by the show’s location at Maccarone, an outpost of a now permanently closed New York gallery that set up shop in the contested Los Angeles neighborhood of Boyle Heights.10 By exhibiting here, Wilson shows unconcern with the structural racism at the foundation of his presence. He focuses on elevating the Black experience as portrayed in objects rather than challenging the white settler activity that makes the whole exhibition—perhaps the whole Los Angeles art world—possible. One may infer that the sizeable production and installation budgets now required to make his work have dulled his barbs. Unlike his 1992 installation at the Maryland Historical Society, Mining the Museum, no institutional violence is uncovered here. The displaced of Boyle Heights are mostly Latinx rather than African American. As the Western rhetoric of painting frequently erased indigenous people from landscapes that were deemed claimable by imperialist interests, so too does the absence of brown Angelenos from Wilson’s frame of reference potentially conflate with previous erasures of indigenous people in the West.

Wilson’s project tracks with the overwhelming focus of African diasporic critiques of colonialism on the Atlantic Ocean and the Euro-American dynamic. That scope does not include meaningful critique of settler colonialism and indigenous genocide, though these historical tendencies are economically linked to slavery and indenture in the Americas and elsewhere. Wilson could have chosen to engage with contemporary Afro-Turks, who are actively reasserting their right to claim Turkishness after a century of erasure and displacement, in the way that the artist asserts their right to that heritage by racializing the Turkish-coded figures in his images.

Fred Wilson, DREAMS (The teeth of the world are sharp) (detail), 2017. Four framed miniatures, vinyl lettering, dimensions variable. Courtesy of Maccarone Gallery and Pace Gallery.

Working within a Western framework in which Picasso’s engagement with Primitivism remains an anchor, neither Wilson nor Hammons chooses to articulate a culturally informed perspective on the West African sculptures that they pull into their own bodies of work. In Wilson’s case, given the historical research and level of detail evident elsewhere in his body of work, this feels like an omission. In Hammons’s case, it reads as part of his larger rejection of constructions of meaning for his art. These sculptures are tourist objects, produced for a global market that exploits authenticity as a marketing trope, but each is still made by traditional methods and from traditional materials. While Wilson preserves and Hammons destroys, both artists accept these objects as stand-ins for the Black body within European modernism, as opposed to representations of African cultural discourses. Each artist employs the sculptures as symbolic markers for Black cultural production or an alternate historical tradition in the West. As a result, Primitivism in Hammons’s and Wilson’s work tracks fairly closely with its early twentieth-century iteration, which introduced indigenous relics into a system of commodity fetishization and consumption.

Isaac Julien’s Playtime (2014) focuses on how art and economics are intertwined.11 Playtime is anchored in a reading of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital (1867) and illustrates how capital flows affect the arts through the lived experiences of people of all classes, races, and social conditions. Conceived for seven channels, Playtime was presented at LACMA as a single-channel projection, and the work in this format was poorly served by the transience-promoting layout of a gallery video installation. Julien’s signature is impeccable production values, and he does not disappoint here, offering up glittering views of London’s financial district after dark and a sweeping desert ridge outside the city of Dubai.

As befits Julien’s Hollywood aesthetic, archetypes embodied by prominent actors populate the scenes in Playtime. Intertitles indicate the “Artist” sequence, set in Iceland, which follows the tall, brooding Ingvar Eggert Sigurðsson amidst modernist architecture and majestic natural wonders. The “House Worker” gives us Mercedes Cabral as a Filipina domestic, isolated in a landscape of luxury in a Dubai tower and, later, in an escape fantasy, wandering the dunes of the Sahara. The “Hedge Fund Manager” embodies Black capitalism in a scene where a suited Colin Salmon, inside a brightly lit office at night, attempts to infuse some soul into the sterile environs with a trumpet. His advisor, a white “bro” type, explicates the baser values of the market while his client, regal in diamonds and stilettos, suggests that the Elizabethan archetype of patriarchal power in a female form can be remade for the twenty-first century in the personage of a self-made Black woman. Questions of whether Black capitalists have the same access as their white counterparts, and whether this access could redeem a system established by the blood of so many commoditized Black bodies, go unstated. In Playtime, the focus is on how the game of contemporary art is but another elaborate credit scheme.

Kapital (2013), a companion film to Playtime, derives from a conversation between Julien and the Marxist geographer David Harvey.12 The film delves more robustly into the physical manifestations of the global system of capital. Anchored in a deep reading of Marx’s Das Kapital, the discussion, which took place at the Hayward Gallery, London, in 2013, benefits from inquiry by audience members, including the late cultural theorist Stuart Hall and historian Paul Gilroy. Harvey proposes that Marx treats capital with a language that resembles animism: “the animal spirits of the entrepreneur.” Market cycles, Harvey maintains, reflect the nature of capitalism, which is to let nonrational energies drive emotional responses to market fluctuations, leading to unpredictable spikes and collapses. The asset markets are implicitly unstable, being based entirely on risk capital and paper valuations, which also characterize the art market. In Playtime, these concepts are dramatized as a complex composition of elements, an ecosystem of financial interests.

Isaac Julien, All that’s solid melts into air (Playtime), 2013. Video still. HD color video, 5.1 surround sound, 01:10:00 min. © Isaac Julien. Photo courtesy of the artist, Victoria Miro Gallery, London, and Metro Pictures, New York.

In Playtime, auction house proprietor Simon de Pury is interviewed by a journalist, played by Maggie Cheung, in a series of expository scenes that link the analysis of Marx in Kapital with the contemporary art market. James Franco plays an art dealer who makes these points more explicit. Here, Stuart Hall’s line of questioning in Kapital feels particularly urgent. Marx, Hall argues, is exclusively focused on production, labor, and the worker, without a mind to the way consumption is enculturated. As such, he can’t account sufficiently for unwaged or underground economies, which are often enacted on bodies doubly marginalized by gender or race. In Playtime, for the most part, authority is granted to male speakers who represent a European-American way of doing business, while women, Asian, and Middle Eastern actors are either inquisitors or mute. Cheung’s line of questioning tests de Pury’s aptitude but doesn’t reflect a contrasting world view. Cabral has the presence of a silent film star, as is required for a role as wordless as any stereotypical maid Hollywood has ever (under)written. The caftaned sheiks of the Dubai Financial Market aggressively trading on the sales floor do not have their own spokesperson among the players. As such, Chinese and Arab neocolonial interests are invoked as current but not presented as being in any way specific to the histories, cultures, or political economies of those regions. Women’s perspectives are telegraphed but only men may articulate ideas. Is this a deliberate study of how omission functions, demonstrating what Hall refers to as “divide and rule strategies”? Or is there something implicit about the framework of theoretical economics that can only push in the direction of reflecting neocolonial hegemony?

For a small but increasingly affluent set in the milieu depicted by Julien, art has gained appeal as an asset class, another financial instrument to leverage. For the rest of us, capitalism is a state of nature—the ocean on which our vessels float. Writer and sociologist Sarah Thornton, author of Seven Days in the Art World (2009), spoke at a LACMA symposium on Julien’s work in May 2019. She said that “beauty and ambivalence” are at play in the artist’s work. But can one be ambivalent and still reckon equitably with the historical violence of the capitalist system as Julien intends to do? Perhaps Julien is not actually ambivalent about capital, which enables the rich aesthetics of his art while instrumentalizing it toward ends beyond his control, but has learned to keep his barbs sheathed for the sake of self-preservation. Playtime makes apparent how little of the contemporary art market actually hinges on the interests or actions of individual artists.

Isaac Julien, Emerald City / Capital (Playtime), 2013. Video still. HD color video, 5.1 surround sound, 01:10:00 min. © Isaac Julien. Photo courtesy of the artist, Victoria Miro Gallery, London, and Metro Pictures, New York.