When its cap is removed its silver needle scintillates promises, inconstancy, ambiguity. —Samuel R. Friedman, “The Needle” 1

I arrive on Sycamore Avenue just south of Santa Monica Boulevard in the early August evening. The RV is parked on the west side of the street. The Clean Needles Now staff prepares for the evening exchange, setting up a table with boxes of syringes, bottle tops for cookers, cotton swabs, and sterilization pads. On the dusty ground next to the table sits a large red disposal container bearing the iconic biohazard logo. The exchange users begin to assemble. Many know each other and strike up conversations, catching the latest word on the street.

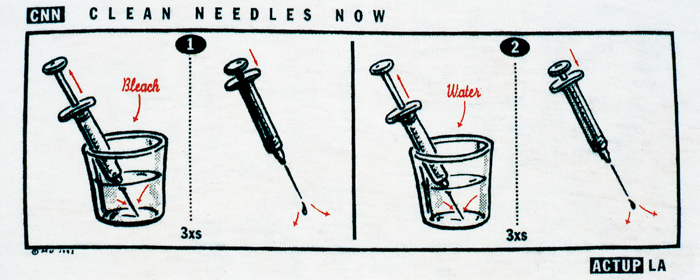

Decal used on Clean Needles Now street exchange vehicle, date unknown. Courtesy Clean Needles Now.

As two staff members give instructions to a small group of volunteers, they introduce me as one of the original organizers of Clean Needles Now (CNN). It has been sixteen years since I last attended an exchange. The faces are new, both in front of and behind the table. Yet, observing the interactions over the course of that Thursday evening, the familiarity of the scene moves me deeply. I recognize from my own memories the non-judgmental and caring disposition of the staff and volunteers. In a society that continues to treat narcotics use as a criminal offense rather than a health issue, injection equipment remains scarce, leading many users to share or re-use their works, which causes infection and poor vein health. CNN is there to reduce syringe scarcity, to help users manage their habit, and to reduce health risks associated with intravenous drug use.2

This article, written in the wake of the twentieth anniversary of the first Clean Needles Now exchange, draws attention to the particular role of artists in its early years. My aim is not to construct an exhaustive history of the program or of all the artists associated with CNN. As a founding member of the art collective Ultrared, my years with Clean Needles Now, from late 1991 to 1996, had a profound impact on the way I practice both art and politics. In my experience, effective cultural actions often occur far from the discourses of art. This is especially true when those discourses only acknowledge drug users and the poor as subjects of art and its institutions, but never as authors of its formulations. CNN represents that unique example where art became the means by which organizers refused the crippling opposition between direct action and direct service.

HIV and Injection Drug Users: The Other AIDS Crisis

A stream of recent documentaries related to the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) has introduced new audiences to the history of AIDS activism in the United States.3 “I’ve seen a lot of different things about ACT UP Los Angeles,” says performance artist, curator, and ACT UP and CNN activist, Marcus Kuiland-Nazario. “There’s always certain personalities that get all the coverage. Depending on who’s writing the history, those are the people who get remembered.” Marcus invokes names of activists ignored by the historical record. “I think of people like Curtis York, a performance artist who is no longer with us. He was a force of nature. The street theater and the street performances that we did were impromptu and so mad. There are these really important people who get left out of the telling.”4

The story told about ACT UP often effaces the diverse geography and practices that made ACT UP such a dynamic political movement. The history of Clean Needles Now is one such local and specific narrative. In 1991, in the midst of ACT UP Los Angeles’s ongoing campaigns for AIDS healthcare and the fight against AIDS stigma, a small group of ACT UP activists began to discuss the need for a local needle exchange program. Initially the needle exchange committee attracted people from different committees, including novelist Steven Corbin and Marcus, both from ACT UP’s People of Color Caucus. Steven recruited photographer Ken Marchionno, at the time a recent East Coast transplant. The committee continued to grow in the autumn of 1991 as founding member, visual artist Renée Edgington, recruited more volunteers to launch the exchange.

Clean Needles Now assembling bleach kits the night before the first exchange, 1992. Renée Edgington is seated in the foreground. Courtesy Ken Marchionno.

Among those whom Renée brought in was club promoter Josh Wells, who had already been organizing art benefits for the Los Angeles chapter of ACT UP. Reflecting back on those days, Josh describes how the needle exchange committee spent nearly a year patiently preparing for the first exchange and learning about harm reduction.5 Developed by drug users, harm reduction argues that health services should meet drug users “where they are,” helping people reduce the harm associated with their choices rather than insisting people get clean and sober before they can access services.6 Josh relates this perspective to CNN: “I had absolutely no desire to get anyone off drugs. We were there to give out clean needles.” As people used drugs, “they protected themselves and their loved ones from HIV, Tuberculosis, and hepatitis C.” The point of the exchange was to give people the tools they needed to make informed decisions about their own health.

Adopted as an official committee within ACT UP Los Angeles in January 1992, the needle exchange committee received money from the general funds to begin stockpiling syringes and other necessary supplies. Drawing on their own experiences as drug users or as friends and lovers of drug users, the committee researched potential locations. The street sites needed to be accessible and part of the routine for injection drug users. Renée secured a decommissioned postal truck out of which they would run the program. And in the weeks prior to setting out to commence exchange, the committee adopted the name Clean Needles Now. Says Josh, “I’m sure Renée called it CNN so that everybody would confuse it with the Cable News Network.” The acronym called attention to the mainstream media silence around what injection drug users could do to reduce the risk of HIV. This type of ironic détournement became a familiar artistic strategy for the group.

Clean Needles Now committee members Neil Klasky and author Steven Corbin helping a user of the exchange, 1992. Courtesy Ken Marchionno.

On Tuesday, June 30, 1992, the CNN conducted their first exchange in the predominantly Latino immigrant neighborhood of MacArthur Park. The long months of self-education and organizing prepared the group for properly dispensing and distributing syringes, the completion of anonymous user surveys, and friendly but efficient interactions with users. When beat cops came sniffing around, the group closely adhered to a script describing themselves as HIV outreach workers. With that first day of exchange, the activists made the commitment for the long-term. “We knew,” says Josh, “that once the exchange started we were responsible for showing up week after week.”

Unlike the community-based AIDS services that defined the first wave of AIDS organizing in the early 1980s, needle exchange was itself an act of civil disobedience. Drug paraphernalia laws in many states make the possession and distribution of syringes a crime. The law rarely distinguishes between distributing rigs and selling drugs, even though the scarcity of injection equipment does nothing to reduce the demand for narcotics. Emboldened by the use of health emergency declarations in San Francisco and other cities, the needle exchange activists felt they had the law on their side.7

Beyond the matters of legality, needle exchange provoked a deeper question about the definition of community used in the term the AIDS-affected community. Ken Marchionno came to ACT UP initially to develop his practice as a photographer in the context of a political movement. One of the few straight men in a largely gay and lesbian organization, Ken humorously recalls being “outed” on several occasions. He found in ACT UP a community where difference, including his own, became the norm. Yet as a norm, the notion of community veiled the contradictions within ACT UP.

Ken recalls conversations during chapter meetings in West Hollywood where the prospects of serving the needs of a population that included men and women as well as people of color provoked resistance among fellow activists. When some ACT UP members responded, “That’s not our community,” Ken and others began to interrogate the biases within the movement. “What community is your community?” Ken remembers asking. “Is it the HIV community? Is it the gay community? Is it the white community?”8 For some in ACT UP, community had become a way of marking exclusions rather than forming bridges and solidarities. By contrast, CNN saw drug users as a population that AIDS activists needed to learn from, advocate on behalf of, and serve.

Instructions for sterilizing used syringes with bleach on the back of the Bleach It t-shirt, designed by Keith Mayerson, 1992. Courtesy Clean Needles Now.

As months passed, it also became apparent that needle exchange required an inventory of points in various sizes to meet the needs of people shooting different kinds of drugs. ACT UP felt the financial drain almost immediately. Eventually ACT UP and needle exchange decided to go their separate ways. Today, Marcus laughs at the absurdity of expecting ACT UP to get in the business of needles, bleach, and cotton. But for CNN, these simple tools had the potential to stem the tide of HIV infection among Los Angeles’s drug using communities. “I don’t think that [our successful work] could have happened,” Marcus adds, “if the split from ACT UP hadn’t occurred.”

The Street and the Body: The Aesthetic Politics of Harm Reduction

In mobilizing whole communities to take to the street and invent new and creative forms of promoting its demands, ACT UP required a communications-based aesthetic. ACT UP graphic artists drew on aspects of advertising and Conceptual art to design an identifiable visual grammar. Remembering his years with ACT UP, Marcus talks about the need at the time for AIDS activist artists “to articulate to the masses the feelings and rage that we were feeling in those meetings and in our personal lives with everyone dying around us.” Iconic images like Gran Fury’s Read My Lips campaign and the performances of Tim Miller directly challenged dominant representations of people living with AIDS as dehumanized or as “victims.” Clean Needles Now required a different approach from ACT UP. Marcus continues: “In CNN we needed makers. We needed people to make a machine that dispensed needles or who could drive the truck. Everybody has a different gift to give.”

Many artists involved in the fight for harm reduction practices received their training in the streets. In the early 1990s, Los Angeles witnessed a steady stream of ACT UP demonstrations. In October 1991, the veto of California gay and lesbian rights legislation AB101 sparked days of mass protests from Silverlake to West Hollywood. Then, in late April 1992, the Rodney King conflagration rocked the city. When CNN began its outreach little more than two months after the citywide rebellion, Los Angeles streets were still high on anarchistic possibility. It was in this context that Marcus describes artists in Los Angeles as “fierce street performers,” possessing skills honed by impromptu performances in the lobbies of single-room occupancy hotels and in the face-to-face battle of defending women’s healthcare clinics from Operation Rescue goon squads. “It was like crazy improv. We would try to think of the most disgusting and vile thing to say to these people. I remember being armin- arm with the people on my side, while chestto- chest with them praying at me. I would go into a really sexy monologue about what I wanted to do to this hot man that was on top of me quoting Bible verses.”

One memorable contribution to the Los Angeles AIDS activist scene was Marcus’s drag persona, Carmen. Appearing in formal performance venues and festivals as well as clandestinely in MacArthur Park, Carmen acted as his Espirismo, or Spirit Guide. “I was in drag all the time doing health education. I stood on the table in the middle of the day by the bus stop. I entertained the moms with their strollers and the guys playing chess with some needles, condoms, and bleach. And they learned. They would come up and practice how to use a condom and how to clean syringes with bleach. The dominant culture thinks working-class Latinos are not ready for that kind of street performance. We proved them wrong.”

Marcus’s description of a street-based performance practice is one that activates the ideological constraints of public space as a site of contested politics. Their harm reduction performances brought CNN activists into constant negotiation with different and antagonistic communities. Thus CNN made a direct link between the street and the body.9 Neither was conceived of naïvely as simply backdrops for protest. Rather, these were sites of knowledge production—knowledge that could save lives.

Keeping Under the Radar: A Collective of (Non)Artists

While most of the original organizers of CNN engaged in some kind of cultural practice as writers, performers, club promoters, or visual artists, Ken Marchionno argues that most of the people became involved for other reasons. “The primary focus in being in CNN was to stop the spread of the infection. That was the most important part.”

CNN volunteer David Lacaillade (with clipboard) collects anonymous user data while peer outreach worker Shanda Vickery (seated) prepares to distribute clean needles during a street exchange in the MacArthur Park neighborhood, circa 1995. Courtesy Clean Needles Now.

In Ken’s recollection, the majority of the early needle exchange committee, which functioned collectively, felt it was important “to make the needle a lesser character in the things that we did.” Minimizing representations of the syringe was seen as a way of working with communities predisposed to drug prohibition. Says Ken, “As long as you’re talking about economic issues, everybody’s fine. But as soon as you say, ‘needle,’ people react with a loud, ‘No!’” In a larger society where abstinence runs deep and where the criminalization of drug use has torn apart communities and resulted in mass incarceration, harm reduction challenges the status quo. Foregrounding an HIV prevention message allowed CNN to introduce the ideas of harm reduction by modeling a different approach. In other words, the point was neither to stigmatize injection drug users nor to fetishize the paraphernalia.

But for some organizers of CNN, bringing the needle out of the shadows was the whole point. For one thing, Josh says, “I don’t think we were the type of people that ever hid anything. Renée had bright red hair with rhinestone, cateyed glasses and she would wear chartreusegreen pants. We were very proud of what we were doing and who we were.” Renée also had the sensibility of a visual artist. Josh laughs, “You’ve got a door of a car, you can’t just leave that blank! You have to come up with a color scheme and a graphic.” The strategic and pragmatic side of artists like Matthew Francis, who was responsible for much of the sculptural and large-scale work in CNN, recognized the need for a visual identity that would announce when the exchange entered the neighborhood even when operated by different volunteers. At the same time, in the early days of the street exchange, some of the activists wanted to stay under the radar as much as possible, at least until the program had gained a foothold.

Clean Needles Now vehicle out on a street exchange in the MacArthur Park neighborhood, circa 1995. Courtesy Clean Needles Now.

Within a year of starting the street exchange, many of the founding organizers had left the group. As Steven Corbin’s health declined, he left CNN to focus on his third and final novel, A Hundred Days From Now.10 Steven died of complications from AIDS on August 31, 1995, at the age of 41. By the end of 1992, Ken had left CNN after clashing with Renée over issues of leadership, marking an end to the collective nature of the organization. In a short time, CNN assumed a conventional non-profit structure, with Renée, who was completely absorbed in CNN as an artist and activist, serving as the organization’s director. She remained director until August 28, 1998, when a car accident while on safari in South Africa claimed not only Renée’s life but also that of her husband and collaborator Matthew Francis.11

Walking into a Hallucination: Needle Exchange as Total Art Activism

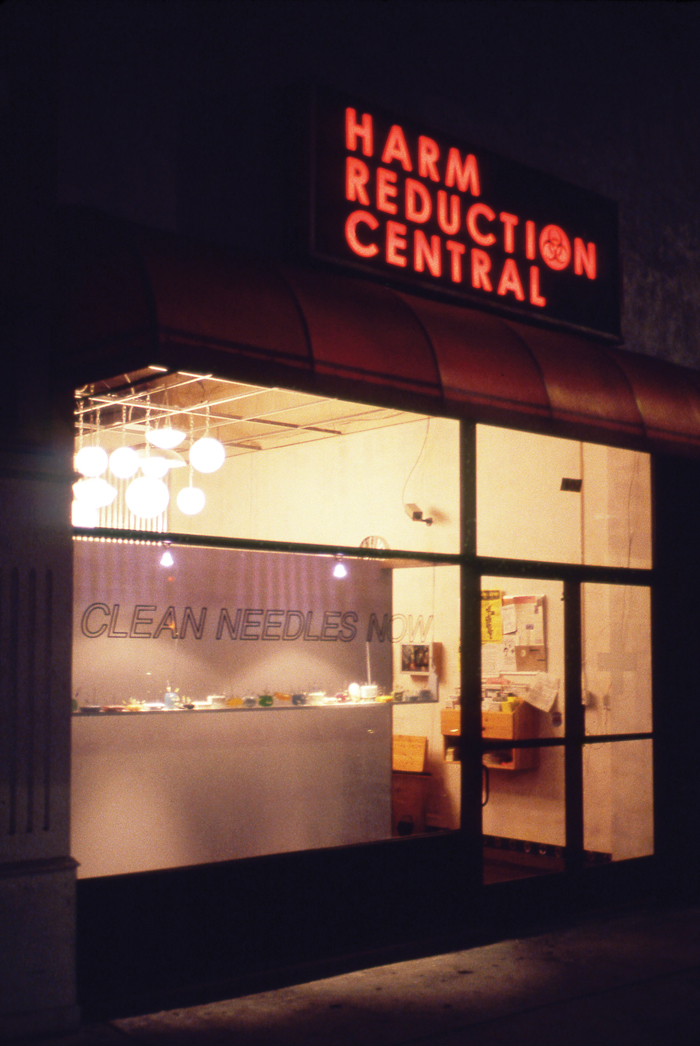

In early 1995, under Renée’s leadership, CNN boldly opened a storefront on Cahuenga Boulevard in Hollywood. Josh remembers how the space became available through the negotiations of city council member Jackie Goldberg, who convinced CNN’s detractors in Hollywood that a storefront would get the exchange off the streets. Christened Harm Reduction Central (HRC), the storefront featured a range of health services and cultural programs for Hollywood’s homeless and runaway youth in addition to providing daily syringe exchange. If the tactic of the early street-based exchange had been to remain under the radar, all holds came off with the opening of HRC.

Harm Reduction Central on Cahuenga Boulevard in Hollywood, date unknown. Courtesy Clean Needles Now.

The artist Kim Abeles had been a supporter of Renée’s involvement in needle exchange from the early days of the program. The two women first met in the late 1980s, when Renée began her studies at the University of Southern California, first as an undergraduate student in studio art and then in the MFA program. Renée asked Kim to serve as an outside member of her graduate committee. Kim was one of the few artists in Los Angeles who understood that Renée’s activism was more than just community service or political agitation. Kim recognized Renée’s work with the activist art collective, Powers of Desire, as well as CNN as a form of cultural and artistic engagement.12 Kim’s appreciation of Renée’s work stemmed from her own art practice as one of the first artists in Southern California to produce work calling attention to women living with HIV at a time when few in the medical establishment acknowledged that women were at risk of HIV and AIDS.13

Both Kim and Renée had intimate experiences with the AIDS crisis through the loss of friends and they shared an investment in AIDS activist art. Kim remembers many of their discussions being focused on dealing with the strong feelings of people who opposed the militant strategies of the AIDS activist movement. Within the art world, those feelings often became manifest in professional retaliation and ostracism by other artists and teachers. Kim recalls conversations with Renée about the importance of retaining a sensitivity to others, “to make sure, politically, that you’re really understanding the nuances of the way things are said.”14

Nurturing a capacity to listen and to work closely with specific and diverse communities became critical for CNN. Kim continues: “One of the main purposes I saw in the storefront, in contrast with what the street exchange had been doing, was that Harm Reduction Central wanted to pull in all those Hollywood kids; teen homelessness was so prevalent at the time.” Adopting what Kim refers to as a “getting them in the tent” approach, HRC offered an appealing space where street youth and users could hang out casually.

Kim describes how HRC stood out from other social service organizations. From its streetfacing display window to the front room where exchange took place and the warren of back offices, the center possessed an extraordinary beauty. “Every inch of it, from wall to fixtures, had something interesting going on.” The deliberate and inviting aesthetics created a comfortable space where exchange activists could teach people about harm reduction.

Walking into Harm Reduction Central was “like walking into a hallucination,” says Marcus. The aesthetic was not the preciousness of a gallery but the union of art with the functionalism of a social service. Furthermore, as Marcus describes it, the beauty of HRC connected directly to the immediate gratification of drugs: “In a positive way, the needle exchange operated under the umbrella of the drug culture, which is, again, the harm reduction philosophy. We did needle exchange the same way a bunch of drug addicts would do it. That’s because we were artists. I felt like it was very parallel.”

A large number of artists came together to create the storefront space. Matthew created a large minimalist structure that served as a counter. Staff and volunteers stood behind the structure while users poured used syringes into an opening in the front. The syringes fell on to a shelf visible through the glass top of the unit. After counting the syringes, volunteers eagerly waited their turn to pull a large metal lever on the side of the structure, like spinning the wheel in a bizarre carnival. A vigorous tug on the long medal arm unleashed an enormous clanking sound, dramatically upending the shelf where the syringes rested. The dirty points then fell through a chute into a red hazmat container waiting at the bottom of the unit. The clattering mechanism provoked cheers among the exchange staff and users, an ambiguous reminder of the transubstantiation of consciousness the now dispensed syringes had performed in the world. As the needle exchange saw more clients, Matthew would eventually produce another such structure with two disposal stations and dual levers.

Directly behind HRC’s front intake room was a social room. Inspired by Warhol’s Factory, the ceiling was meticulously covered in tinfoil and the walls painted in candy-colored angular sections. The combination of colors, light, and angles embraced visitors in a delirious disequilibrium. The only furniture in the room was dozens of beanbag chairs. The room functioned as a multipurpose space housing workshops for youth, a drop-in center for people to nod off while coming down from a high, or a meeting space for the staff and volunteers.

The Harm Reduction Central disposal unit created by artist Matthew Francis, date unknown. Courtesy Clean Needles Now.

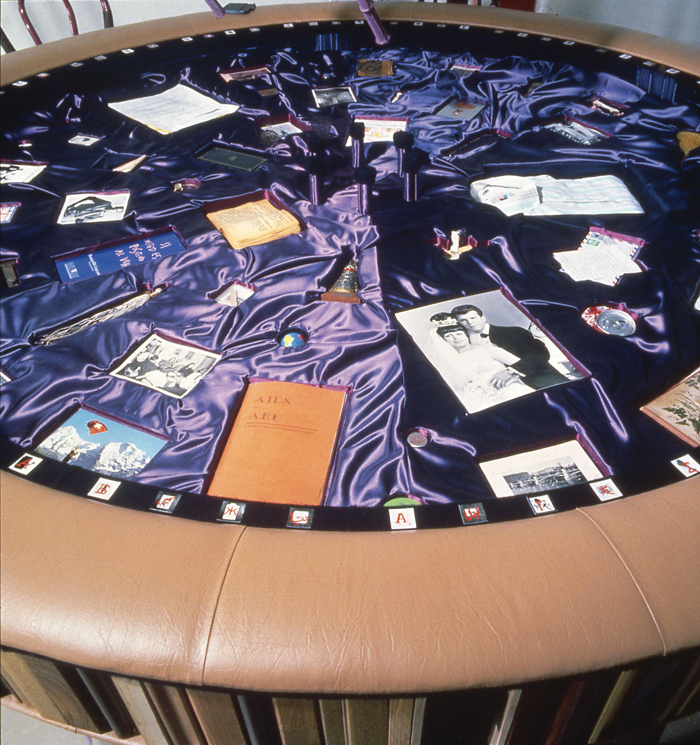

The back offices housed a medical examination room, rooms for staff and outreach workers, and a central meeting area. Each office had its own theme, like the Tiki room or the “homage to Kim Novak” room, designed by artists such as Hell Kitty creator Jim Yousling, who passed away on New Year’s Day in 1995, shortly before HRC opened. The centerpiece of the meeting area was a large round conference table constructed by Kim Abeles. Titled Found Voices (Dedicated to People with AIDS), much of the table had a clear top through which one could examine a vast array of objects and photographs of objects related to people living with AIDS. Made in 1989, Found Voices was one of the earliest artworks to acknowledge women with AIDS. The table accompanied a soundtrack composed by Barbara McBane from interviews conducted by Kim and Peter Bergmann with people infected with HIV at a time when few survived. A large handmade chandelier assembled from detritus and found materials by the artist James Reva hung over the table. Perhaps best known in Los Angeles for his bitingly satiric window designs for L.A. Eyeworks on Melrose Avenue, Reva designed much of HRC’s interior details, as well as many of the window displays that announced harm reduction messages to passersby on Cahuenga. He passed away from AIDS in 1996.

Found Voices (Dedicated to People with AIDS), 1989. Sculptural components by Kim Abeles, interviews by Kim Abeles and Peter Bergmann, with sound design and editing by Barbara McBane. Table and chairs made of wood, enamels, soil, felt and satin; objects belonging to PWAs; small photographs of objects with handwritten alphabets found globally; table: 7-ft diameter. Courtesy Kim Abeles.

The HRC storefront window became a fixture of Hollywood for its spectacular scenes of lights and ironic political statements. Instead of boutique gifts for hip shoppers, HRC windows displayed psychedelic objects like syringe-decorated bars of colored soap or Frankenstein toys designed by street youth. As an outreach worker for Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Marcus held an office in HRC and served as one of the main facilitators of the youth art projects. His broken toy workshops with teens remain to this day a topic of conversation among users of the Hollywood exchange site. Along with his collaborator, writer Cynthia DeSantis, Marcus had the teens assemble a new toy from a selection of broken parts. They then wrote narratives about their toys, reflecting on their struggles with homelessness, addiction, and their experience living in a society that stigmatizes and criminalizes adolescents, particularly queer youth.

An important policy of the workshops was that young people were always welcome, whether high or sober. For Marcus the open policy exemplified harm reduction in practice. “It really bothered me that for so many social service organizations the kids had to be sober in order to participate. I thought, ‘That’s fucking stupid.’ You get in trouble when you’re high. So we said: ‘Get high. Come in here, play with some toys, and get off the street. Go nod off in the corner or be tweaked out with your toy.’ It was so important for us to do this; to give these kids somewhere to go when they were high, because the trouble happens when you’re high.”

Homophobia and Prohibition: The Different Conditions of the Crisis

Despite the differences between the two organizations in how they defined community, CNN retained much of ACT UP’s activist DNA. CNN adhered to a similar AIDS cultural analysis around the politics of representation regarding drug users. As importantly argued by art critic Douglas Crimp and a number of artists and cultural critics in the mid-1980s, AIDS cultural analysis asserted that at the heart of the AIDS crisis was a political crisis of representation. The constant invocation in politics and the media about the risks of HIV for the “general public” reinscribed the homophobic notion that gay people and anyone else living with AIDS existed outside of any conception of the public. The image of a “general public” immune to the virus became not just an effect of the AIDS crisis but the lethal justification for political inaction and moral backlash. The representation of the “general public” provided the ideological conditions by which a viral infection exploded into a health crisis.15

Far beyond providing the basis for an activist art, AIDS cultural analysis codified the tenants of the direct action wing of the AIDS movement. At a fundamental level what distinguished Clean Needles Now from ACT UP were the material conditions of needle exchange itself. ACT UP saw its role as pressuring the state to expand access to medical research, healthcare, culturally specific prevention, etc. For ACT UP and the larger AIDS movement, fighting AIDS was synonymous with transforming representations of the public by negating homophobia. This civil rights approach saw the state as malleable to demands from mass mobilization.

In the national harm reduction movement, a version of AIDS cultural analysis argues that the stigma attached to drug users conditions the crisis similarly to homophobia. A culture of prohibition only recognizes recreational drug use as a criminal problem and as a symptom of personal irresponsibility. Drug users thus possess an outlaw status in society, living beyond the boundaries of the “general public.”

Harm reduction advocates then and now in cities elsewhere in the United States have urged their local governments to implement needle exchange programs as part of a comprehensive AIDS prevention plan. However, CNN’s primary demands to city and county governments were that they provide the legal protections for needle exchange to exist, and that they offer funding and interconnection of services so that CNN could do the job itself. Beyond this, the fundamental political demand of CNN was the end of drug prohibition (i.e. legalization). These different perspectives between ACT UP and CNN on the role of the state would impact their respective definitions of direct action, their strategies of representation, and their uses of art.

Art Below the Skin: The Emotional Habitus of CNN

The accumulated effect of the interdependence between the aesthetic and the daily practice at HRC resulted in a dramatically different feeling from anything cultivated in ACT UP. Marcus reflects on this difference: “In ACT UP we were just so angry. I’m still angry. But with CNN, it was something we could do directly. It had a different feeling to it. It wasn’t so tinged with anger. When I left needle exchange at the end of the day I felt that I had helped someone receive something tangible.”

Plexiglas plinth filled with used needles collected during regular exchange operations, date unknown. On top, deluxe bleach kit and needles storage container including bleach and water bottles, alcohol pads, tourniquet, pellet cotton, sterilized bottle top, and a compliment of 1 cc unused syringes. Kit designed by the artist collective Powers of Desire. Courtesy Clean Needles Now.

The “difference of feeling” that distinguished ACT UP and CNN exemplifies what sociologist and former ACT UP Chicago member Deborah Gould has called the emotional habitus—the emotional disposition and condition of AIDS activism and social movements in general.16 Gould asserts that social movements generate emotional signifiers that organize the ambivalent affects that otherwise overwhelm people in moments of profound crisis. Much has been written about ACT UP and the role of art in sustaining a movement “united in anger to end the AIDS crisis through direct action.” In contrast, CNN promoted a “non-judgmental approach [that] allows exchangers to feel comfortable talking about what they do, asking questions, and therefore talking about their behaviors.”17 Whereas ACT UP saw the role of art as keeping alive the fires of rage, CNN exhibited an addict’s sensibility, part compulsive care for the body and part aesthetic excess.

Reflecting on CNN’s specific approach to AIDS activist art, Kim Abeles speaks about a sophistication that conceptualized the role of art at “a different level.” From bleach kits that contained pornographic Polaroids by artist Bill Rangel to a CNN delivery truck that parodied a Red Cross vehicle, Kim describes the CNN aesthetic as having “a strange sophistication that blurs art and practical needs so closely that you can’t untwist them. One doesn’t supersede another.” In terms of which was more important, the art or the public health intervention, Kim answers, “One was interdependent upon the other. One wouldn’t have functioned without the other. And that is really different from donating art to raise money. CNN really put art in daily dialogue instead of in a separate space, like a traditional social service attitude.”

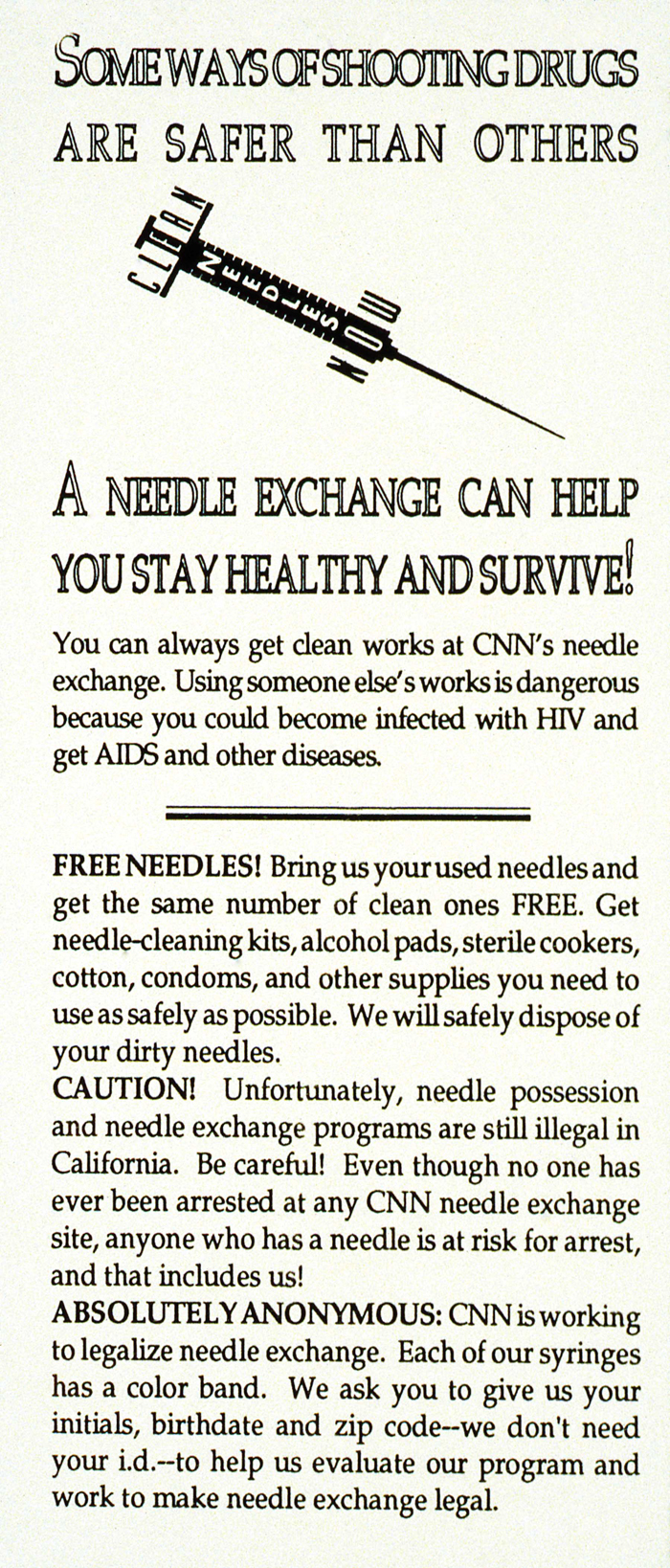

Clean Needles Now information pamphlet, circa 1995. Courtesy Clean Needles Now.

And yet it is important to note that in its first five years, CNN mounted significant art-related benefits to pay for the ongoing expenses of syringe distribution. During their time with ACT UP and CNN, both Marcus Kuiland- Nazario and Josh Wells organized numerous art benefits. However, unlike the blue-chip art auctions of the large AIDS non-profits, the art benefits Marcus and Josh organized followed a strong egalitarian ethos. Beginning in 1993 at the Los Angeles Center for Photographic Study, the Shooting Gallery benefits, also held at Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE) and Bergamot Station Arts Center, listed all art for the same modest price and capped the number of works one person could purchase. Josh describes the philosophy of the Shooting Gallery benefits as being “about involvement.” He continues, “Anyone could donate a piece and whoever bought it for whatever reason, was participating in something.”

For one of the Shooting Gallery fundraisers, Josh and Renée parked the CNN bronco in the middle of the gallery, defiantly reminding the art world of the inextricable relationship between cultural action and HIV intervention. This same strategy motivated Renée and Matthew to mount the exhibition State of Emergency in 1994, at the Armory Center for the Arts in Pasadena. The exhibition featured the dispensary unit from HRC placed inside the gallery along with a full complement of syringes and biohazard containers, the latter labeled with the dates and times they were filled. On the gallery walls, Renée and Matthew exhibited a series of light boxes with photographs of the needle exchange in action.

Overall, through its practices, Clean Needles Now deconstructed the old opposition between direct action and social service, an opposition that motivated many activists and artists to join ACT UP when it was founded in New York in 1986.18 In keeping with Gould’s assertions, CNN organized affect under different conditions than ACT UP. In confronting the choice between an inward attention to community service and an externally focused form of direct action, it refused that dichotomy. Like a needle below the skin, art became the means by which harm reduction delivered lifesaving services in resistance to the dominant structures (and its aesthetics) of prohibition. With a large storefront window announcing “Clean needles save lives,” the hallucinogenic tableaux of Harm Reduction Central created an alternative social space where drug users acted as agents in a community and as managers over their own addiction.

Afterword: CNN and Art Practice Today

Today, CNN continues to provide harm reduction services for as many as 5,800 injection drug users a year. For many AIDS activists like Marcus and Josh, CNN is the living legacy of ACT UP and Los Angeles’s AIDS movement. The longevity of the program is evidence of the effectiveness of the organizing strategies artists in particular can adopt in social interventions. Directly engaged in an urgent political and social crisis, Clean Needles Now defines a concrete notion of the site of reception. The people who receive its services experience real consequences. Thousands of people are alive today as a result. While none of the original activists remains associated with CNN, many of its current staff and volunteers are themselves former users of the exchange. And while the role of art was initially interdependent with administering a health intervention, the art meant nothing if the service did not save lives.

For Marcus, it was a natural progression that CNN would move to its storefront location. “It was better to have a center where you could make appointments, where doctors could come, and where counselors could come and see people.” However, tireless campaigns by neighborhood improvement groups and Hollywood revitalization boosters have subjected CNN to the same bullying as its homeless users. In time, gentrification pressures in Hollywood forced CNN out of its lease on the Cahuenga Boulevard space. During one of the organization’s many periods of transition, an unpaid invoice for a storage space resulted in losing all the artwork produced for HRC. After hearing the news of the tragic loss, Marcus mused, “It’s just like a drug addict to lose his stuff.”

Inside Harm Reduction Central, date unknown. Gathered around Matthew Francis’s syringe collection unit, from left to right: Renée Edgington, peer youth counselor and artist Cluster Fuck, volunteer James “Uncle Jimmy” Hulse, and an unidentified man. Photograph by Michael Chiabaudo. Courtesy Clean Needles Now.

Since the closing of Harm Reduction Central in the early 2000s, CNN has returned to being an entirely street-based intervention. CNN continues to experience the pressures from gentrification and NIMBYism that force the program to regularly change its sites. In early November 2012, the Hollywood site on Sycamore Avenue was forced to close. CNN now facilitates a new site in the back parking lot of L.A. Gay & Lesbian Center, just a block away from the first Hollywood exchange site. A new site in South Central only became possible with the official change of the organization’s name to the generic-sounding, Los Angeles Community Health Outreach Project (a necessary change that recalls earlier debates about underemphasizing the needle in needle exchange). As Shoshanna Scholar, the current director, explains, a storefront location today would have to negotiate strict guidelines limiting proximity to schools and playgrounds, making only the most remote location available.19 In keeping with the culture of prohibition, the policy willfully refuses to acknowledge that drug users live in every community.

For CNN today, an urgent question is: How do our cultural practices resist the stigmas of poverty and drug use that condition and are conditioned by the tyranny of private property? Because of the consequences for actual lives and communities, that question raises the stakes above and beyond polite conversation about social practice art. Perhaps CNN and artists committed to social change will only secure larger transformative power in a movement of justice for and by the poor. Organizing the affective space around poverty presents us with an urgency just as great today as twenty years ago when the AIDS crisis left tens of thousands in America dead and entire communities wiped out. CNN’s refusal to choose between negating the world that exists and creating the world as we desire it, and to instead invent the aesthetics that organize the affective terrain “below the skin” makes it a valuable example that is as much a challenge as an invitation.

Dont Rhine has been involved in HIV/AIDS organizing since 1989. He co-founded the international sound art collective Ultra-red in 1994 (www.ultrared.org). Dont also teaches in the low-residency Visual Art MFA program at Vermont College of Fine Arts.