Becoming Robot, Nam June Paik’s recent exhibition at Asia Society, demonstrates how the artist’s work from 1960 to 1990 anticipated many of the technologies and attendant philosophical debates of our contemporary age by several decades. The Korean-born artist, who died in 2006, is widely known as a pioneer in electronic music and time-based art forms, including performance and video. Less commonly acknowledged is Paik’s innovative approach to questions of the body’s interface with technology, exploring an ontological space that we refer to today as “transhumanist” or “post-human.”1 Paik’s prescience is worth considering not only because his speculative futurism offers insights into our present-day condition of ubiquitous, hand-held computing, but also because his cross-cultural references—as a Korean artist working in Germany and the United States— articulate a counterpoint to dominant, Enlightenment-derived thought trends with respect to questions of autonomously generated intelligence and artificial life.

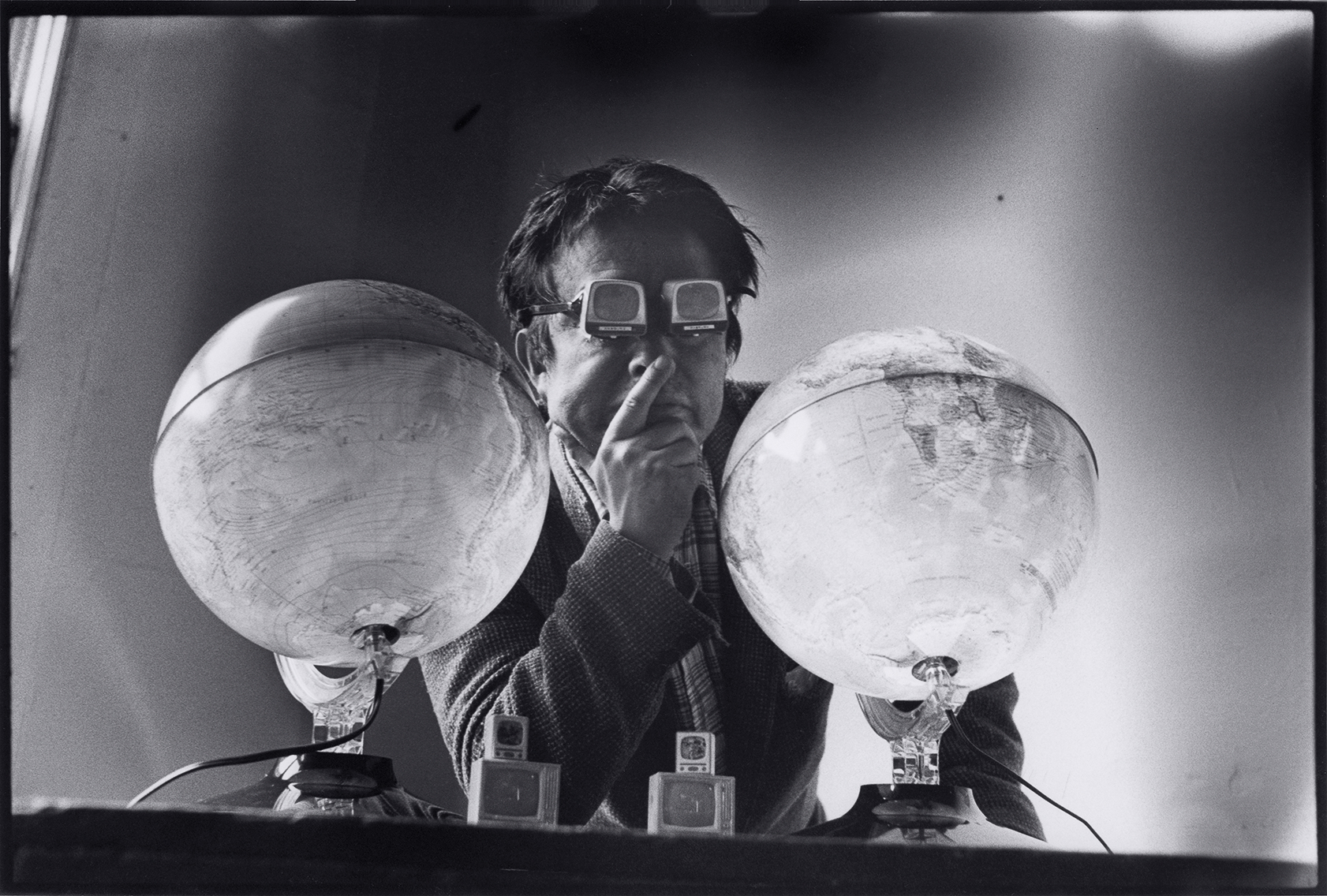

Whereas Paik has heretofore been primarily treated as a pioneer only in the narrower technological space of video art, Asia Society Director Melissa Chiu and curator Michelle Yun make the case with this exhibition for Paik as a visionary who predicted contemporary technological and media developments. Yun argues that Paik’s investment in audience participation in interactive works, from his early audiotape installations to Participation TV (1963), “anticipated twenty-first century discussions about social interaction through multimedia platforms.”2 Chiu repeatedly references an image of Paik wearing TV glasses and contemplating two globes as a precursor to our globally interconnected era of ubiquitous computing, invoking Google Glass in both her introduction to the catalog and a later interview with Paik’s former assistants and his nephew, who is executor of the Paik estate. The impulse to rethink Paik’s legacy in our present day is understandable given that so many of his predictions have been made manifest in contemporary forms, from Facebook to YouTube. However, anticipating social computing is but one facet of Paik’s foresight. His “desire to humanize technology”3 situates Paik at the forefront of contemporary thought regarding artificial or autonomously generated life and intelligence, exploring possibilities that engineers and research scientists have even now only begun to engage.

Nam June Paik, Presentation of Good Morning Mr. Orwell, at the Kitchen Gallery, New York, on December 8, 1983. Photo © 1983 by Lorenzo Bianda, Tegna, CH.

The Paik exhibition occupies two floors of the Asia Society Museum’s Upper East Side townhouse. Visitors are encouraged to begin on the third floor, with Good Morning Mr. Orwell (1984), a public video broadcast shown internationally that celebrated the start of Orwell’s titular year while establishing Paik’s own cultural context alongside artists, musicians, composers, and commentators, such as John Cage, Joseph Beuys, Merce Cunningham, Laurie Anderson, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Peter Gabriel, and George Plimpton. Aired on the first day of 1984 on New York’s WNET/ Thirteen, the work is an avant-garde variety show billed as “Art for 25 Million People” that reveals both the technological ambitions and limitations of its era. This is a side of Paik we know well—simultaneously esoteric and populist, ensconced in the downtown scene, enamored of new imaging techniques and willing to embrace their glitches. A humorous, lighthearted tone characterizes the broadcast despite the Orwellian dystopia that under-pins the whole effort, which is subtitled “Thank goodness you were only half right!”

By opening with this work and a series of 1980s portable Transistor Televisions painted with crude smiling faces, the exhibition foregrounds Paik’s interest in popular accessibility via celebrity, his downtown New York social and artistic milieu, and the cheerful humor of his aesthetic approach. This frames Paik within an established discourse as a utopian technologist, defined artistically by his Euro-American peer group, with little attention to his Asian origins. Paik’s nephew Ken Hakuta acknowledges that within contemporary art circles, “He’s not identified as an Asian artist, as such.”4 Paik himself was reluctant to embrace labels such as “Asian,” stating, “I can compose something, which lies higher (?) than my personality or lower (?) than my personality.”5 However, the works installed on the second floor tell a more complex story of Paik’s cultural identity and how it can inform our understanding of what it means to “become robot” in the coming digital age.

Nam June Paik, Transistor Television, 2005. Permanent oil marker and acrylic paint on vintage transistor television, 12½ × 9½ ×16 inches. Nam June Paik Estate. Photo: Ben Blackwell.

To the question of his adherence to Zen or Buddhist teachings, Paik would reply, “No, I’m an artist,”6 despite regularly incorporating the Buddha’s image and Zen principles into his work from the 1970s onward. He explained, “I’m not a follower of Zen but I react to Zen the same way I react to Johann Sebastian Bach.”7 Rather than a religious interest, Paik’s engagement with Zen is indicative of his ability to bridge Eastern and Western canons to create art that builds upon multiple traditions simultaneously. Paik made clear his interest in melding Western critical theory with Zen philosophy in pronouncements such as “Cybernetics, the science of pure relation, or relationship itself, has its origins in karma,” which he followed with a discussion of Marshall McLuhan and Norbert Wiener.8 Works such as TV Buddha (1974) and Whitney Buddha Complex (1982), neither of which is included in the Asia Society exhibition, would seem to be more interested in the mass media and commercial implications of the Buddha images they appropriate than in their potential for transcendence. Buddha’s place in these works is as giver and recipient of the gaze, the same place that viewers themselves are meant to occupy in interactive works such as TV Chair (1968).

Paik’s work in robotics and wearable computing is notable precisely because it consistently maintains connections with and interest in the condition of embodiment. Robot K-456 (1964), among the earliest works in the show, is a remote-controlled robot that reduces human reference to a schematic armature representing head, arms, and legs. In place of eyes, it has cameras; in place of a mouth, a speaker. Remarkably, while skin and hair are absent, Paik is careful to preserve sexual characteristics. Originally endowed with both breasts and penis, the robot was castrated before reaching New York.9 K-456’s chest remains marked with urethane foam pads that resemble fatty tissue. She is an example of the archetype described by Donna Haraway as “a creature in a post-gender world.”10 K-456 retains her excretory function, defecating beans while she moves. Says Ken Hakuta, “What I remember is he wanted to make it with human functions. You know, he wanted it to eat and he wanted it to defecate, he wanted it to have breasts.” He further recalls, “One day my father said to Nam June, ‘Why don’t you let me help you? I will make a much better robot.’” Because the one he made, it didn’t even walk properly. It kind of limped along, you know? Nam June said, no, he liked it just like that. He didn’t want a more perfect robot.”11

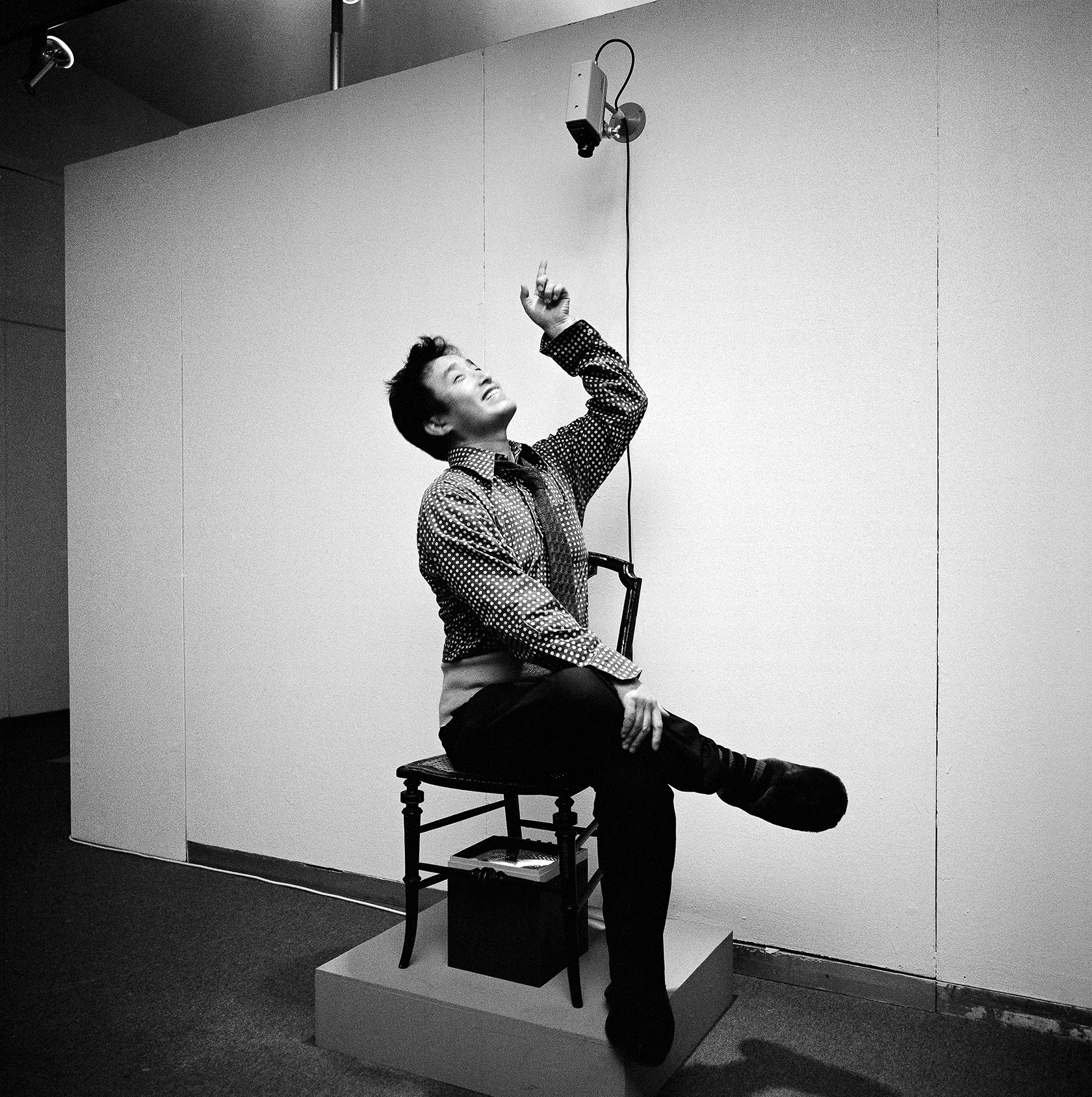

Here we see how Paik’s interest in futurism deviates from aspirational visions of transhumanist idealism—the belief that technology will liberate us from our bodies—to instead embrace the messiness of being alive. Another scatologically inclined work is TV Chair, which incorporates a Plexiglas seat and a closed-circuit camera that displays an image of the sitter’s face directly underneath his or her rear end. As futuristic visions, these works may well be unique in the art world in that they embrace “aliveness” as implicit in the basest aspects of body-experience—our need to expel waste, our desire for sexual contact, our capacity for procreation—essential aspects of existence that Paik does not judge as lowering intellect or morality, but simply includes. In doing so, they suggest an ontological reference point for artificial life that diverges from the dualism of Enlightenment thought, positioning Paik as a post-humanist (evolving through but retaining the human) whose world view deviates from that hierarchical frame of mind over body and human over animal.

Nam June Paik sitting in TV Chair (1968/1976) in Nam June Paik Werke, 1946–1976: Music, Fluxus, Video, 1976. Photo © Friedrich Rosenstiel, Cologne.

The prevailing view among engineers and researchers in the field of autonomous generated intelligence (AGI) (popularly known as “artificial intelligence” or “AI”) is that computers can be engineered to achieve consciousness by synthetic means. Experts differ on how that consciousness would manifest or what its implications might be. In this field of research, neural networks are likened to computer circuits that transmit packets of information both within and across systems. Some seek to achieve consciousness within a single cybernetic unit, while others anticipate distributed intelligence activated over networks. Models of such distributed consciousness are identified in social systems, from insect swarms to human relationships, and bear resemblance to Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari’s concept of the “rhizome” or “abstract machine” that “ceaselessly establishes connections between semiotic chains, organizations of power, and circumstances relative to the arts, sciences, and social struggles.”12 In contrast to Paik’s interest in future forms that retain vestiges of the body, most AGI researchers in the present day appear to be invested in generating consciousness within environments that lack haptic input—servers, not cyborgs—seemingly in the belief that a computer consciousness could exist and be recognizable to humans without engaging the physical world through embodied forms.

From a critical race and gender theory perspective, such an expectation of intelligence without the body reflects a worldview described by Sara Ahmed as “a phenomenology of whiteness.” “Whiteness,” she writes, “could be described as an ongoing and unfinished history, which orientates bodies in specific directions, affecting how they ‘take up’ space.”13 Citing Husserl, she articulates a white phenomenology as that which takes the self as “a zero-point of orientation,”14 experiencing physical and environmental stimuli as external to an intrinsic consciousness. In contrast, Frantz Fanon describes how “In the white world the man of color encounters difficulties in the development of his bodily schema. Consciousness of the body is solely a negating activity … a third-person consciousness.”15 Ahmed further explicates Husserl’s phenomenology as that of a “body-at-home,” one situated within a framework of alike-ness such that no friction, such as that which Fanon describes, is encountered in the shift from interiority to externality. This is the condition of “the body before it is racialized”16 or gendered; before the self encounters social circumstances of difference and marginalization. As such, phenomenological experience of a world in which one is “alike” can be experienced from a position of pure consciousness; while those who encounter the world from a position of difference find that their experiences are determined by the fact of their bodies, resulting in what W. E. B. Du Bois termed “double-consciousness.”17 This ontological space is one that current AGI research has yet to address.

As a consequence, Paik must distance his conceptual viewpoint from his Asian cultural context in order to be perceived as “alike” enough to be taken seriously by the Euro American art communities in which he operates. Even so, he continues to emphasize the role of embodiment, messy and visceral, in his futuristic vision, remarkable because it deviates from the image of computer intelligence as intellectual-analytical rather than physical-experiential. In the former, an intelligence could be transferred from a human host body to a robotic one, or exist with no host body at all, with minimal alteration. An example of this expectation appears in Neil Blomkamp’s 2015 film Chappie, which fictionalizes an established philosophy of autonomously generated intelligence as adhering to the developmental stages of human childhood. The audience’s empathy with the titular robot is ensured by his child-like, emotionally naive experience of a harsh world, not by his physical resemblance to humans, which is limited to upright ambulation and some very simple LED screen “expressions.” Once endowed with autonomous cognition, Chappie develops the capacity to back up and transfer not only his own intelligence but that of two human characters as well. In the film’s dénouement, Chappie’s mortally wounded creator awakens in an android body and seems to resume his life uninterrupted, with no indication that he has been changed by the experience. Chappie is a film that bears metaphorical resonance with themes of racial and class conflict in contemporary South Africa, depicting a world anchored by a profit-driven social system dependent on an exploited underclass that must be controlled at any cost. Regrettably, the film falls short, not only by neglecting to include a single black leading character in a story fundamentally shaped by the experience of black South Africans, but also by failing to accommodate for the degree to which the consciousnesses of the two uploaded humans—a South Asian man and an Afrikaner woman—are informed by the facts of their bodies as carriers of social difference.

Nam June Paik, Li Tai Po, 1987. 10 antique wooden TV cabinets, 1 antique radio cabinet, antique Korean printing block, antique Korean book, and 11 color TVs; 96 × 62 × 24 inches. Asia Society, New York: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Harold and Ruth Newman, 2008.2. Photo © 2007 John Bigelow Taylor Photography, courtesy of Asia Society, New York.

At this time, such a cognitive transfer remains firmly within the realm of science fiction. Even so, at least one prominent futurist, Martine Rothblatt, has argued that it is far enough within the realm of possibility that we ought to start rewriting our laws to accommodate the civil rights of intelligent robots and uploaded human beings. Biotech tycoon Rothblatt is the owner of Bina48, an animatronic head built by Hong Kong-based Hanson Robotics into which Rothblatt claims to be gradually transferring the consciousness of her wife, Bina Rothblatt. Bina48’s creator, David Hanson, has stated that “the perception of identity … is so intimately bound up with the perception of the human form.”18 Nonetheless, Martine Rothblatt is adamant that “someone who doesn’t have a body could still be afforded human rights, if they have a mind.”19 Rothblatt’s denial of the role that embodiment plays in the formation of consciousness is indicative of a transhumanist, neo-Cartesian world view that does not reconcile with the fact that Bina’s life experience as a black woman in a same-sex partnership is necessarily characterized by some degree of social friction. This is not to suggest that the totality of Bina Rothblatt’s consciousness is defined by external constructions of her identity, but rather to articulate the need for “a middle way approach” to cognition, “of ‘neither-duality-nor-identity,’”20 as called for by Taiwanese Buddhist scholar Chien-Te Lin.

Paik’s animated and wearable sculptures reflect a world view informed by both Cartesian and Buddhist theories of consciousness. With their social and physical connectedness to human bodies, they typify Haraway’s concept of the cyborg as “a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction.”21 Rather than describe this integration in terms of explicit race or gender (as Bina48 seeks to do by replicating Bina Rothblatt’s physical appearance), Paik articulates forms of human-machine integration that raise questions of identity in a post-human context from a Buddhist-informed, holistic point of view. This is akin to the concept of “interbeing” promoted by Vietnamese Zen Buddhist Thích Nhất Hạnh, who states, “Consciousness always includes subject and object.”22 Paik’s Robot Brain (1965) is clearly not the location of consciousness, as it sits airlessly beneath a bell jar: a collection of wires, plugs, and a date-planning notebook, showing no visible signs of life. The work suggests that a robot’s brain is simply hardware, but consciousness is located elsewhere, in embodiment; the presence of the body, whether real or abstracted, is necessary to breathe life into these inorganic beings. At the same time, Paik’s objects—however animated—necessarily return to a state of non-being or thing-ness, both because they come to rest and because they ultimately belong to the static realm of display, within the art gallery or museum.

This is best expressed through his Family of Robot (1986), a mother, father, and child built from the artist’s characteristic cathode-ray televisions that serve as vessels for the frenetic activity of media transmissions. The viewer recognizes in these sculptures the signifiers of a family unit, and feels a certain identification as parent or as child (or both). The videos displayed on each of the robot’s screens imply the personality of each archetype. Life, these works suggest, passes through us like a transmission, rather than emerging from deep within us. The robot family’s data banks resemble Thích Nhất Hạnh’s “store consciousness,” which he describes as retaining infinite knowledge that “can be perceived directly in the mode of things-in-themselves, as representations, or as mere images.”23 Stephen Vitiello, Paik’s former assistant, remarks on Paik’s engagement with Zen philosophy, “It’s funny because on the one hand, he was, I think, sometimes critiquing Asian culture. But then he makes a piece so poetic, like TV Buddha, which both borrows from, and maybe critiques, but also deeply appreciates, something very deeply rooted in Zen culture.”24 Says Lin, “Rather than admitting to an eternal soul which migrates from one birth to the next, Buddhism instead posits the existence of a ‘stream of consciousness’ or ‘mental flow’ which is nothing more than the changing continuity of a person’s karma.”25 This view, in which a transition between physical phases is both change and continuity, contrasts with the Christian-Cartesian “I” of the soul as well as with the Greek concept of metempsychosis, revived by the Romantics, which posits the rebirth of an immortal self in a new body.

Nam June Paik, Reclining Buddha, 1994/2002. Two-channel video installation with two 9-inch color monitors and reclining stone Buddha; 6½ × 20½ × 12 inches. Nam June Paik Estate. Photo: Ben Blackwell.

A performative object such as TV Bra for Living Sculpture (1975) responds directly to the wearer’s physicality, emphasizing our sexual natures. This work, made famous by Paik’s longtime collaborator and chief performer, Charlotte Moorman, is a wearable video synthesizer connected to Moorman’s cello. Like Bina48, TV Bra is notable for being technology that is specifically gendered female, still a rare occurrence in our culture that treats maleness as the default. TV Bra functions simultaneously as a work of video, performance, and sound art. Like the instrument itself, TV Bra represents augmentation of and integration with the body, rather than the flesh’s obsolescence. Opera Sextronique (1967), a recital in four movements that was cut short by Moorman’s arrest for indecent exposure, incorporated Paik’s Light Bikini (1966/75), a gas mask, and an assortment of props as accessories to the cellist’s fleshy sensuality. Argued Paik, “The purge of sex under the excuse of being ‘serious’ exactly undermines the so-called ‘seriousness’ of music as a classical art, ranking with literature and painting.”26 Works in a separate gallery at the Asia Society Museum celebrate Moorman’s remarkable openness and bravery as a performer in her collaborations with Paik and many other artists. Says Hakuta, “I think Nam June was very much struck by Charlotte’s charismatic performance.”27 Moorman’s body was of ongoing interest to Paik as a site of artistic intervention, just as her exceptional skills as a musician complemented his radical ideas about sound and composition. Her zaftig femininity and her Southern belle charms are repeatedly acknowledged in the exhibit. She performed with other downtown luminaries of the era, including Yoko Ono, La Monte Young, and John Cage, but it is with Paik that she remains most closely associated. Much of the Asia Society homage is based on Joan Rothfuss’s biography Topless Cellist: The Improbable Life of Charlotte Moorman (2014). Rothfuss attributes the brevity of Moorman’s engagement with the downtown scene to an insistent physicality and emotional unruliness that also precluded her career in classical performance. That same disruptive charisma and unwillingness to follow scores to the letter excited Paik, who continued to work with her long after his contemporaries had written her off.

Nam June Paik and Howard Weinberg, “Topless Cellist” Charlotte Moorman, 1995. Video, color, sound; 29 minutes. Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York. Image courtesy Electronic Art Intermix (EAI), New York.

Haraway, citing Chela Sandoval, articulates a figure who is too much “animal, barbarian, or woman” not enough “man, … the author of a cosmos called history.”28 Charlotte Moorman seems to fit that description—situated at the center of a historical moment that she experiences as an outsider, ultimately rejected by many in the mid-century avant-garde for refusing to play by the rules set for her by others. Moorman’s ostracism by the downtown art elite, led by Cage, resembles what Roland Barthes calls “inoculation.” As Chela Sandoval describes it, “consciousness surrounds, limits, and protects itself against invasion by difference,”29 as an ontological position that lends itself to supremacy and fascism in multiple forms. Notably, Ono and Paik remained connected with Moorman when others did not, suggesting that their experiences of cultural difference (and Ono’s position as a woman in a male-dominated scene) prompted them to approach her with greater compassion. Chela Sandoval calls this “effective unity”30 between individuals and groups outside the mainstream that reject the hierarchical values of an imperial ruling class. Paik counters Moorman’s rejection by the avant-garde with a doctrine of “intercourse between the body of Charlotte Moorman and the TV set,” or what he casually refers to as a “tele-fuck.” Says David Joselit, “the boundary between self and non-self is no longer marked by the skin, but distributed throughout the body as a hybrid surface of flesh and scanning.”31 Counter to the Euro-American norm of separation and categorization, Paik appears to reject prudishness and embrace a philosophy of mind-body integration. He again melds Eastern and Western concepts when he writes, “The Buddhists also say … Relationship is metempsychosis.”32 By relating to other beings or other objects, we transcend the self.

It is disheartening that the Asia Society exhibition mostly overlooks Paik’s Korean heritage and Japanese university education as factors in his overall artistic output while simultaneously celebrating him as an example of a canonical Western artist. The technophilic attitude too often applied to the artist fails to account for either the irreverence or the critical stance of a work such as First Accident of the Twenty-First Century (1982), in which Robot K-456 ventures out of the Whitney Museum onto Madison Avenue and is struck by a waiting car, representing what Paik called “a catastrophe of technology in the twenty-first century” and what Michelle Yun describes as “a reminder of technology’s limitations and the importance of prioritizing humanity over scientific innovations.”33 Yet this combination of humor and detached observation, on which the exhibition’s curators repeatedly remark, reflects what can be viewed as a Buddhist perspective on the part of the artist and as a manifestation of the influence of Eastern philosophies on much of Western conceptual art. Given the degree to which Asian engineers and entrepreneurs are helping to design and build the technologies of the future, it seems fitting to allocate some space within the philosophical framework of futurism to accommodate a range of Eastern points of view. Embracing Nam June Paik as an artist whose combination of Asian and Western bases of knowledge positioned him as an oracle of our contemporary networked age would be an excellent place to start.

Anuradha Vikram is a curator, critic, and educator based in Los Angeles, California. Her primary interest is racial and gender equity in art, technology, and post-human discourse. She is Director of Residency Programs at 18th Street Arts Center, faculty in the Graduate Public Practice program at Otis College of Art and Design, and a contributor to print and online publications nationwide.