Bauhaus 1919-1933: Workshops of Modernity presents a chapter of Modernism stripped of its myths, ideologies, and politics. Dusting off the general concept of the Bauhaus as a generic icon of the international modern style, curators Barry Bergdoll and Leah Dickermann seek to approach the Bauhaus “…not as an artistic style or a programmatic movement but as a vibrant school.”1

The succinct title of the MoMA show is more telling than the general public might think. It responds to the last and only Bauhaus exhibition in America, Bauhaus 1919–1928, which was organized in 1938 at the then–new MoMA. Curated by Walter Gropius, the show epitomized Alfred H. Barr Jr.’s definition of modernity. Gropius focused primarily upon the period from 1922-1928, during which time he dominated the school as its director. Effectively, Gropius excluded Hannes Meyer’s tenure from 1928-1930 and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s directorship from 1930-1933, and included hardly any material in reference to the Johannes Itten-dominated, early Expressionist years from 1919-1922.

MoMA’s present show sets the record straight by covering the full narrative. However, it needs to be considered that although no comprehensive Bauhaus exhibition has been organized in the U.S. since 1938, a mountain of literature has been published since—much of it in English. Bauhaus research has amounted to an industry. So while the average visitor might find the existence of an early, Expressionist Bauhaus surprising, a more educated audience may well be informed about its basic tenets.

Marcel Breuer with textile by Gunta Stölzl, African Chair or Romantic Chair, 1921. Oak and cherrywood painted with water-soluble color, and brocade of gold, hemp, wool, cotton, silk, and other fabric threads, interwoven by various techniques with twined hemp ground. 70 5/8 x 25 9/16 x 26 7/16 in. Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin. Acquired with funds provided by Ernst von Siemens Kunststiftung. Photo: Hartwig Klappert.

Upon entering the exhibit, visitors walk through the chronology and workshops of the Bauhaus. The first large room is dedicated to the early years and shows works by Itten and his Preliminary Course students. This versatile landscape includes Itten’s large, brightly colored, abstract painting Ascent and Resting Point (1919), which is reminiscent of Robert Delaunay’s similar motifs. Here also is Marcel Breuer’s early Romantic Chair (1921, also known as the African Chair) with upholstery designed and made by Gunta Stölzl. The Romantic Chair marks the expressionist debut of Breuer’s long career in Modernist design and architecture. Such items as student Franz Scala’s Chagall-esque painting The Dream (1919), texture studies, and bookbinding designs (by Anni Wottitz and other students) for mystical texts from African tales to German myths are indicative of the early Bauhaus’s quest for religion, mythology, and irrational experience. Itten, who was the high priest of the quasi-religious sect Mazdaznan, encouraged this tendency.

Also on display is Gropius’s 1919 Bauhaus Manifesto, which is illustrated by Lyonel Feininger’s woodcut representing what has been dubbed the “Socialist Cathedral.” It is important to remember that medievalist cultural nostalgia held sway over the Bauhaus for some time. While Gropius had a clearly rationalist and pragmatic program, not even he had been unaffected by the profound irrationalism in Germany immediately following World War I, and he, too, looked back to medieval cathedral builders as models for collaboration and spiritual community.

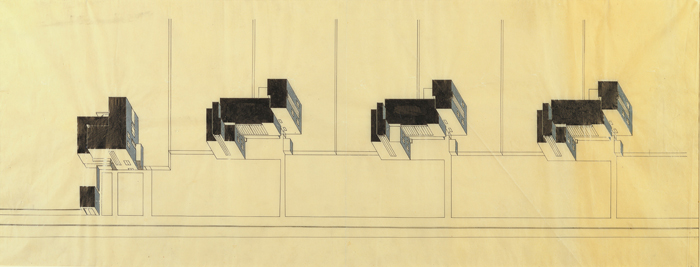

Walter Gropius, Bauhaus Master Houses, Dessau, isometric site plan, 1925-26. Ink and gouache on tracing paper. 14 15/16 x 35 11/16 in. Harvard Art Museum, Busch-Reisinger Museum. Gift of Walter Gropius. Photo: Imaging Department © President and Fellows of Harvard College © 2009 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

The second room in the exhibition displays increasingly professional product designs and prototypes accompanied by art works of Paul Klee, Vasily Kandinsky, Josef Albers, Oskar Schlemmer, and others, as well as photos by Lucia Moholy and László Moholy-Nagy. This part culminates in relics from the well-known 1923 Bauhaus exhibition. The main event of the 1923 exhibition was the design (by painter and textile workshop leader Georg Muche) and construction of a square-shaped, flat-roof house, complete with Bauhaus-designed interior, furniture, and household objects. At MoMA, Breuer’s furniture, Alma Busher’s nursery design and toys, Bauhaus postcards designed by students and faculty, and Herbert Bayer’s and Moholy- Nagy’s graphic designs are shown along with some pioneering architectural drawings, including Farkas Molnár’s outstanding house design, Red Cube (1923).

What the MoMA exhibition does not account for is the curious shift from the Bauhaus’s early Expressionism to the more reductive and controlled functionalist aesthetics of the 1923 exhibition, which was held under the spell of Gropius’s slogan: “Art and Technology: A New Unity!” The temporary revitalization of the German economy by late 1922, a drifting away from the war experience, the Itten-Gropius conflict, and the aggressive presence in Weimar of the Dutch De Stijl’s Theo van Doesburg in 1921 and 1922, likely resulted in a return of the Bauhaus’s basic concept and practice to Gropius’s original ideas. However, visitors to the MoMA show would have to do further research, beyond reading the exhibition wall labels, to understand this context.

The rest of the Weimar period is richly documented by Herbert Bayer’s Constructivism and De Stijl-inspired geometric, red-and-blue-and-yellow kiosk, pavilion, cinema, and other urban structure designs. As noted by Hal Foster in his catalog essay, these spectacular structures point ahead to the “society of the spectacle” described by Situationist Guy Debord in 1967, while at the same they targeted the urban consumer.3

Marianne Brandt, coffee and tea set, 1924. Silver and ebony, lid of sugar bowl made of glass. Tray: 13 x 20 1/4 in. Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin. Purchased with funds from the Stiftung Deutsche Klassenlotterie Berlin. Photo: Fred Kraus. © 2009 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

The architectural designs and workshop products of the Dessau period presented in Bauhaus 1919-1933: Workshops of Modernity include Gropius’s designs for the Bauhaus campus and the masters’ houses; Breuer’s tubular chairs, textile works, graphic design, and photography; Meyer’s more austere designs for, and photo documents of, the Federal School of the German Trade Union Federation; Mies van der Rohe’s designs and furniture pieces; and a number of student works. The multidisciplinary character of Bauhaus education is richly documented in the case of Josef Albers, whose exhibited works include paintings on lass, furniture, glass dishes, graphic design, photos, and wallpaper. Similarly, Marianne Brandt’s brilliant metal tea set and ashtrays are accompanied by her collages. The only surprisingly underrepresented master is Oskar Schlemmer, whose sole painting on display is MoMA’s own Bauhaus Stairway (1932). Minor exceptions to the fact-conscious curatorial concept are the inclusions of several works by Moholy-Nagy dating from before and after his time at the Bauhaus; the fascinating puppets that Klee made for his son outside his Bauhaus activities; and a painting by the Hungarian artist Alexander Bortnyik, who lived in Weimar at the time and had friends in the school, but was not a Bauhaus student.

While acknowledging the short-lived Expressionist period, Bauhaus 1919-1933 predominantly features objects of design that fall under the recognizable category of pragmatic, functionalist modernity. As a result, the present exhibition seems to perpetuate, rather than correct, the general image of the Bauhaus as rationalist, politically progressive, and as such, “socialist” institution. After all, the great majority of its design was intended to provide an affordable yet comfortable lifestyle to lower middle class households with modern aesthetics as a bonus. The formal vocabulary of Modernism was, however, not the exclusive property of the political left. As Winfried Nerdinger writes in his revealing essay on the role that many Bauhauslers undertook under National Socialism, “modern forms were transferable to any context.”4 For example, while in the early 1920s the rationalist-functionalist style stood for a collectivist future opposing nationalist conservatism, by the late 1920s this style was embraced by the increasingly affluent middle class and was considered frivolous by left-wing observers. Art critic Ernst Kállai, editor of the Bauhaus Journal (1928-1930), discerned the new aspiration to “objectivity” and reminded readers that the Bauhaus had distanced itself from its original social commitment. “The new Berlin despises the swollen marble and stucco showiness of the ‘Wilhelmian’ public buildings and churches,” he wrote in 1930:

…but it revels in the hocus-pocus of megalomaniac motion-picture palaces, department stores, automobile “salons” and gourmet paradises with their shrieking advertisements. This new architecture, the slender nakedness of its structure shining far and wide and bathed in an orgy of lights at night, is by no means, so we are told, ostentatious; it is rather “constructive and functional.” …Bauhaus style. But let us take heart. For small homeowners, workers, civil servants, and employees the Bauhaus style also has its social application. They are serially packaged into minimum standard housing.5

Flying in the face of the commonly held assumption that the Nazis solely advocated neo-classicism to further their agenda, Nerdinger sets out to show how the Nazis shunned neither the rationalism and economy of modernity, nor the new technologies. Indeed, in the 1930s they embraced what he calls “a Nazi-specific concept of the beauty of technology” in which modern forms became part of their ideology. As Nerdinger goes on to say, “Modern form was assigned in Nazi ideology the task of expressing technical values…so some Bauhauslers designed private industrial facilities with all the hallmarks of the ‘New Building’”6 in the Third Reich.

Anni Albers, wall hanging, 1925. Wool and silk. 84 7/8 x 37 3/4 in. Die Neue Sammlung the International Design Museum Munich. Photo: Archive Die Neue Sammlung © 2009. The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The transferability of the Modernist object to different political contexts, the dramatic historical background of the school, and its tense inner history challenge the curatorial concept of a purely educational Bauhaus. Moreover, the “objective” image of the Bauhaus glosses over its status in Weimar Germany, where the conservative majority perceived it as controversial and even potentially politically dangerous. MoMA’s exhibition runs vintage footage demonstrating how the modern housewife used modern household items to make life more comfortable, but does not show footage of Nazi parades and the increasingly hostile political environment that would confront and even shape the future outcome of the Bauhaus to a great extent.

In its day, the Bauhaus was never regarded as merely a school. It was both a fighting force and a fortress in the culture war of post-World War I Germany and the greater European cultural and political theater. Beside art’s social commitment to progress and “the people,” at stake was leadership and control of the international avant-garde. Among the unfunded artists’ groups that made similar claims in the same timeframe, such as De Stijl, the dispersed and decentralized Dada, the remains of Futurism, the constructivists, surrealists, and others, the Bauhaus was a towering institution with state and city subsidies, and housed in a brick-and-mortar headquarters. As an established bastion of the avant-garde, the Bauhaus’s oxymoronic position was highly coveted by many rivals.

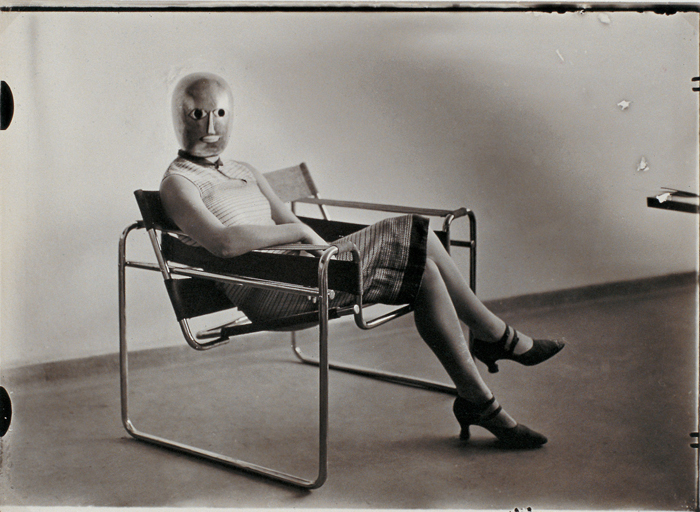

Erich Consemüller, untitled (woman in B3 club chair by Marcel Breuer wearing a mask by Oskar Schlemmer and a dress in fabric designed by Lis Beyer), c. 1926. Gelatin silver print, 5 x 6 3/4 in. Private collection. © Estate of Erich Consemüller.

Already in 1938, at the very beginning of its afterlife, Gropius’s curatorial concept for Bauhaus 1919-1928 revealed the level to which the legacy of the Bauhaus was contested. Gropius sanitized it in the name of objectivity, deeply convinced that only he—founder and developer of the school—was qualified to interpret its true heritage. Its afterlife was divided by the Berlin Wall, but the Bauhaus retained its ties to politics. For progressive thinkers in the West it was perceived and eventually embraced as a sanctuary for both rationalist design and freedom of imagination. However, in the Socialist bloc of the 1960s, the Bauhaus was considered an outdated bourgeois enterprise of which only Marxist Hannes Meyer remained as an acceptable iconic figure. Taking up the Bauhaus’s heritage, the Ulm Hochschule für Gestaltung (College of Design) opened in 1953 under the direction of former Bauhaus student Max Bill; the college was anointed by Walter Gropius. In response, Dutch artist and CoBrA cofounder Asger Jorn reached back for inspiration not to the designers but rather to the artists in the Bauhaus, when, in that same year, he wrote:

[A] Swiss architect, Max Bill, has undertaken to restructure the Bauhaus where Klee and Kandinsky taught. He wishes to make an academy without painting, without reaching into the imagination, fantasy, signs, symbols—all he wants is technical instruction. In the name of all experimental artists I intend to create an International Movement for An Imaginist Bauhaus.7

In 1957, Jorn’s movement merged with several others concerned with the active shaping of urban space to create the Situationist International. An anti-establishment, revisionist, ew-left movement, it was rougher and more radical than the Bauhaus, but was a virtual continuation of tendencies inherent, if not fully developed, in the school.

Oskar Schlemmer, Bauhaus Stairway, 1932. 63 7/8 x 45 in. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Philip Johnson.

The American reception of the Bauhaus was not favorable in 1938, and, although the myth of the school has been thriving in scholarship, the tendency to strip the Bauhaus of all ideologies and present it “objectively”—as does MoMA’s exhibition— has been consistent.8 Consequently, American Modernist artists, in particular the minimalists, looked to the Russian avant-garde rather than the Bauhaus for their model, because the former remains a repository of unattained goals and dreams while the Bauhaus achieved and objectified most of its (often changing) goals within the boundaries of capitalist society.

If MoMA’s recent Bauhaus exhibition seems lackluster, perhaps this is because focus on the Bauhaus as a school flattens the image of the Bauhaus as a political entity. But it may also be due to the distance we have from the spirit of Modernism, its intellectual excitement and ethical commitment. A twist in the present reception of this workshop of high Modernism may be our sense of having lost the fun and mess of Postmodernism, too. The clarity of Modernist forms may be esthetically desirable now, but they are perceived as too low-tech and their moral contents do not necessarily come across today. To grasp the significance of the international style in design, and understand the social meaning of mass production in 1920s Europe in our current era of global trade, requires historical knowledge. “Simplicity” and mass production today are not situated on an ethical high ground but are merely corporate business tools. The simple, functional, and often rudimentary objects of the Bauhaus don’t bring to mind, in our moment, the great ambitions and the social concepts of their makers; rather, they bracket the Bauhaus’s great experiment in an historic time, when people were typing away on mechanical typewriters.

Éva Forgács is a critic, curator, and art historian. She teaches at Art Center College of Design and Otis College of Art and Design.