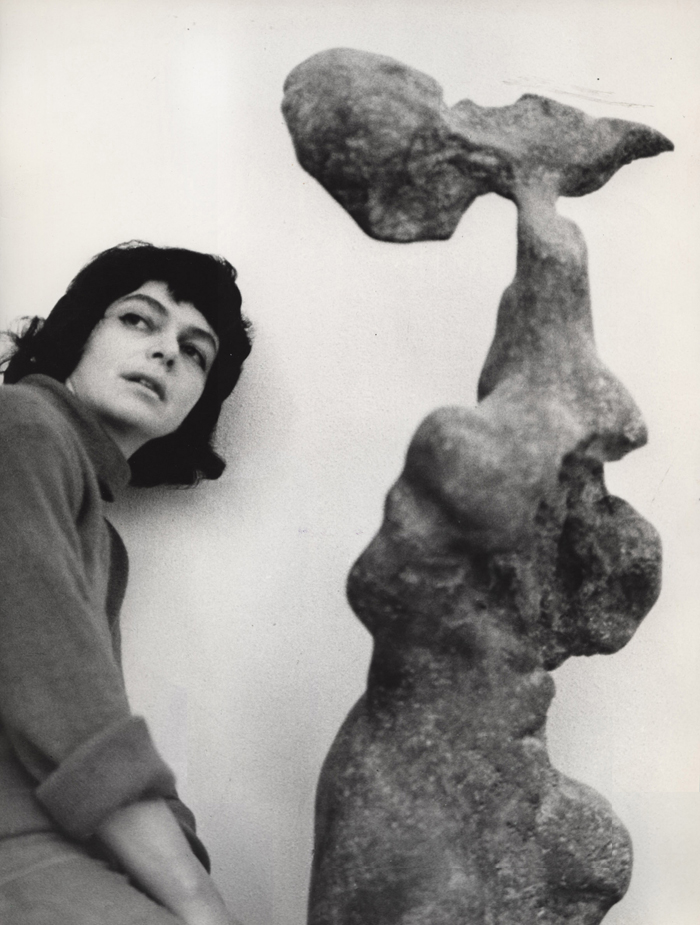

Alina Szapocznikow with her work Naga (Naked), 1961. The Alina Szapocznikow Archive/Piotr Stanislawski/National Museum in Kraków. Photo by Marek Holzman, courtesy the Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw.

AVENIR

DEVENIR

SOUVENIR

—Cia Rinne, Notes for Soloists

In her 1979 essay, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” Rosalind Krauss stated that the primary logic of sculpture “is inseparable from the logic of the monument. By virtue of this logic a sculpture is a commemorative representation.”1 According to Krauss, this logic began to fail in the nineteenth century, when sculpture found its “sitelessness.” The modernist monument became more and more an abstraction, “functionally placeless and largely self-referential.” The sculptural base, in sum, became the key objet, not the iconic commemoration. In the twentieth century, base turned more base—leading to the site/non-site specific works of Robert Smithson and Carl Andre, for example. With postmodernity, the sculptural logic turned a-material, “organized instead through the universe of terms that are felt to be in opposition with a cultural situation.”2 Krauss productively uses the semiotic square (Klein diagram) to register these oppositions, thus mapping the axis between “architecture/ non-architecture” as the location of the work of Sol LeWitt, Richard Serra, and Christo, and “landscape/non-landscape” as the venue for Smithson, Andre, and Nancy Holt.3 It should be noted that these oppositions tended towards a concrete external relation: the sculptural object in literal relation to the surrounding non-sculptural objects.

In similar dialectical fashion, the work of Polish sculptor Alina Szapocznikow, who died of cancer in 1973, has finally come to the attention of the West. A 2009 group show, Awkward Objects, at the Warsaw Museum of Modern Art included a two-day conference on Szapocznikow, which featured presentations by Griselda Pollock and Cornelia Butler.4 This was followed by a series of small gallery exhibitions and group shows in both Europe and the United States. Now we have the Hammer exhibition (February 5, 2012–April 29, 2012), which travels to the Museum of Modern Art (October 7, 2012–January 28, 2013) by way of the Wexner Center for the Arts (Columbus, Ohio, May 19, 2012– August 5, 2012). But critical moves to position Szapocznikow “in opposition with a cultural situation,” to grasp her via the postmodern dialectic, have not been as successful or as satisfying, in part because no one can fix the locus of the logic in play—either in terms of the representative aesthetic or the significant cultural situation.

As noted by Polish art historian Jola Gola in her 2011 essay, “L’Œil de Bœuf— Finding the Key to the Works of Alina Szapocznikow,”5 attempts to precisely unlock the logic in Szapocznikow’s work are various and pervasive, and, I would add, strangely insistent. In addition to the numerous Polish and French explications chronicled by Gola—including, among other things, the impression or trace, ars moriendi, general corporeality, persistent duality, and Gola’s own Bataillesque reading of une petite mort, the paradox of death and orgasm—are those proffered in the two major English language publications to date, the Awkward Objects monograph and the catalog for Sculpture Undone. For Pollock in Sculpture Undone, Szapocznikow iconically encrypts biographical and historical trauma, and, for Butler, evidences a feministic (if not feminist) Surrealism, a kind of sculpture féminine.6 For its part, the Hammer’s exhibition wall texts referenced Pop Art, Nouveau Réalisme, and 1970s feminist art practices. But perhaps “key” should be turned from noun to adjective, and Szapocznikow’s œuvre considered as providing a codex to the movements of its time. For the logic of Szapocznikow is that there is no oppositional logic. Rather, there is an immanent sublime which is absolutely presented7 — wherein the fragment is always complete, memory present-tensed, and contradiction that which includes diction itself.

At the Hammer, the pieces were presented chronologically through three galleries, underscoring the biographical/historical element foregrounded by way of two documentaries that prefaced the show, the impressionistic Trace (Helena Włodarczyk, 1976), which set Szapocznikow’s figures in a series of urban mise-en-scènes and the artist in her studio and among her appreciators, and the plainer En Pologne: 6ème partie — De la liberté des beaux arts ou Jdanov n’est pas polonaise (Jean-Marie Drot, 1969), in which Szapocznikow tells the director, “I don’t want to talk about my experiences in public. I’ve already told you everything.” When asked directly whether her work is an echo of war and disaster, she says, “It is to be expected, but not intended. It’s not done on purpose. I feel embarrassed to belong to the same race that invented the camps and everything I went through. So I don’t talk about it.” In fact, Polish art historian Aleksander Wojciechowski has noted that Szapocznikow “avoided the subject virtually obsessively.”8 As obsessively as everyone else cites it.

For part of the difficulty in thinking about Szapocznikow’s sculptures lies in the facts of Szapocznikow’s biography, and its cultural fascinations. The story is historically harsh: death of her father when she was a child, death of her brother after the war, internment in two ghettos (Pabianice and Łódz ́), followed by two concentration camps (Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen); working as a nurse with her doctor-mother in one ghetto and one camp; terminal tuberculosis diagnosis at 23, experimental treatment resulting in sterility; secret adoption of son; shuttling between Warsaw and Paris; constant financial difficulties; breast cancer diagnosis at 43; mastectomy three years later; death the following year, at 47. It is these specific conjunctions of tragedy to corporeality to history which prove so critically irresistible, as the sculptures themselves are often rot caught—the capture, permanent and impermanent, of permanence and impermanence themselves, a contrapuntal punctum, where it is life that obscenely extrudes from death.

So Souvenir I (1971) is seized upon by Pollock, among others, as one of the most directly haunting pieces, and, thus, easiest to read: a large photo collage featuring Szapocznikow as a smiling young girl in a swimsuit, straddling what were her father’s shoulders, supplanted in the work by a projected skein of wool, the upside-down image of the dead face of a concentration camp victim on the skein, that thick-lipped death’s head resting on the throat of another gap-mouthed corpse, whose pitted eyes point to the jutting skeinskull who hovers just to the side of the young girl’s shoulder. The piece is coated in yellowed polyester resin, hardened and curled like a lambskin scroll set in stone—the Torah as death warrant, and vice versa. It is the story of Abraham when there is no angel to stay the hand or substitute sheep for son. It is a sacred work in the Agambenian sense: representing the unrepresentable, marking that which is marked as set apart, that which may be slaughtered but not sacrificed. The allegorical properties are almost perversely pointed, such that even registering the patently symbolic feels strangely profane, and if we take the clinical concept of perversion as one who delights in making oneself object for another, then much of Szapocznikow’s work is perverse, and, moreover, the perversion of perversion, in which the objected one is turned into the object of another one, not the viewer necessarily, but the process of viewing as such—the image turning into an interpretive hall of mirrors to which the image can only return.

Alina Szapocznikow, Tumeurs personnifiées (Tumors personified), 1971. Polyester resin, fiberglass, paper, and gauze; ranging from 13×221/16 ×133/8 inchesto 5 15/16 × 9 1/16 × 6 5/16 inches. Zacheta National Gallery of Art, Warsaw. © The Estate of Alina Szapocznikow/ Piotr Stanislawski/ADAGP, Paris. Courtesy Zacheta National Gallery of Art, Warsaw, and Agencja Medium Sp. Z o.o.

This reflexivity is echoed through other motifs in the exhibition, and materially replayed by way of the various formal movements Szapocznikow moved through. Thus, the embalmed/exhumed body is Expressionistically rendered in Ekshumowany (Exhumed, 1957), a rough bronze figure, its life-sized legs and arms appearing rudely amputated, its hollowed belly mirroring the hollow of its open mouth; Surrealism shows in Torse noyé (Headless torso, 1968), the headless pale trunk of a woman, her pendulous breasts animated by bright pink aureola, set in pillows of lava-like black polyurethane foam; and returns again in the more Nouveau Réalisme gesture of Tumeurs personnifiées (Tumors personified, 1971), in which partial and transmogrified renditions of the artist’s head, composed of polyester resin, fiberglass, paper, and gauze, appear as largish misshapen stones.9 In Szapocznikow’s Conceptual proposal, Patinoire dans le cratere du Vesuve (Ice Rink in the Crater of Vesuvius, 1972), Pompeii figures as both metaphor and allegory. Composed for a competition to design an international cultural park on top of Mount Vesuvius,10 Szapocznikow was invited to submit by Pierre Restany. She proposed an ice skating rink, complete with ski lifts and artificial snow, set at the bottom of a volcanic crater. Skaters would glide and twirl under paper lanterns to taped Russian waltzes; as curator Manuela Ammer has noted, given the skaters could not know when the volcano would next erupt, “they were, literally, skating on thin ice.”11 Szapocznikow’s submission ended with a death wish: “If one day during a figure skating competition, the Peggy Fleming of the moment performs her moves in the field in the iced-over crater, and if we, spectators awed by her prodigious and trivial pirouettes, are swept away by a sudden eruption of lava, fixed for eternity like the Pompeiians— then the triumph of the instant, of the transitory, will be complete. A fleeting instant, a trivial instant, such is the only symbol of our terrestrial passage.”12

Alina Szapocznikow, Lampe–bouche (Illuminated lips), 1966. Colored polyester resin, metal, and electrical wiring; ranging from 11 1/4 inches to 17 15/16 inches high. The Estate of Alina Szapocznikow/Piotr Stanislawski. © The Estate of Alina Szapocznikow/Piotr Stanislawski/ ADAGP, Paris.

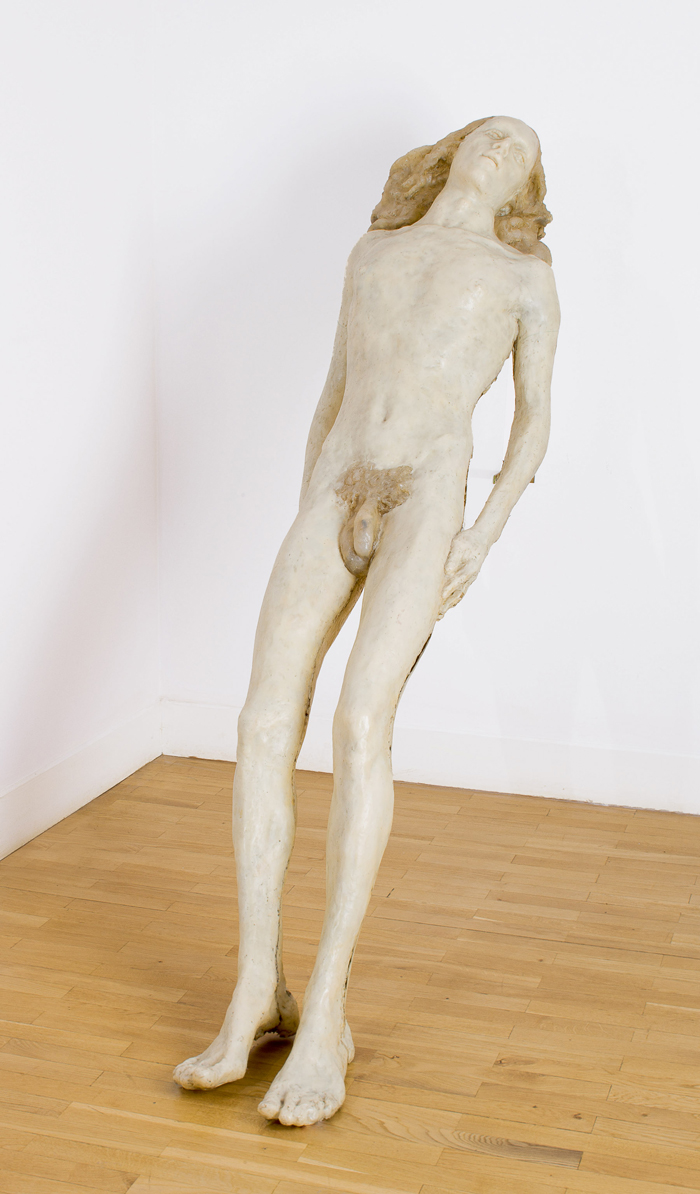

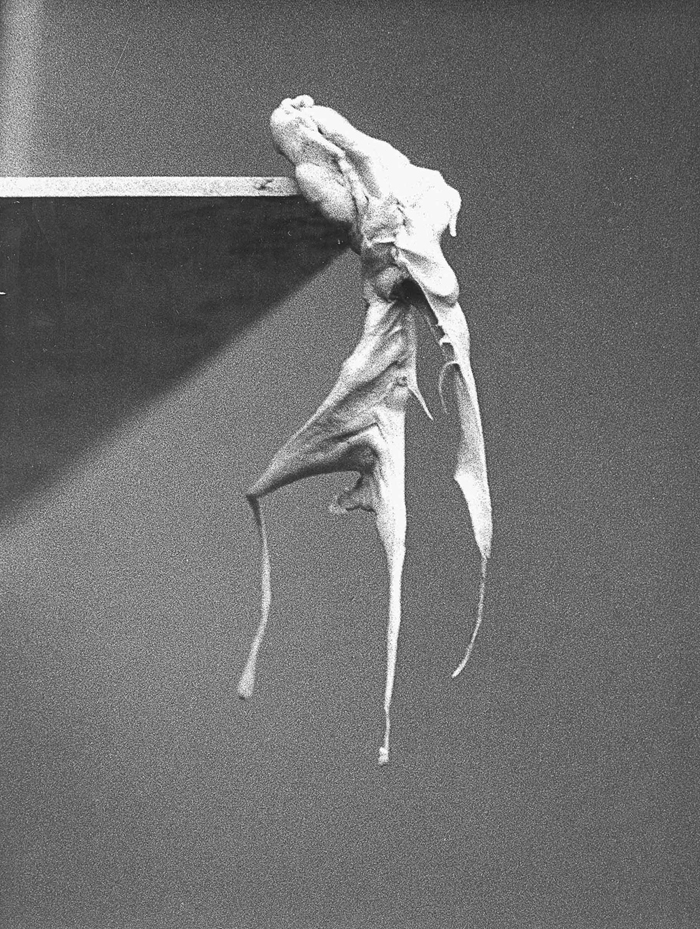

Alternatively, one could trace the allegory of the monumental-transitory through the exhibit as it shifts from Ekshumoway to a series of works in which Szapocznikow made life-molds of herself and her adopted son. In Piotr (1972), the nude male figure is fully formed but leans improbably backwards, without seeming support, the polyester resin seeming like aged white marble. In Herbier XII (Herbarium XII, 1972), the same figure is served up flattened, fragmented, and folded, its polyester resin reading as flayed or stripped skin.13 Or discern the gesture of the industrialized body-object in the protoPop Człowik z instrumentem (Man with Instrument, 1965), a thick-legged standing cement statue, headless, shoulders slumped, a car part running from neck to crotch/crotch to neck forming a selfpenetrating phallus-trunk, or in the Pop Lampe-bouche (Illuminated Lips, 1966), a series of six table lamps, each lamphead made of an illuminated mouth, the skin around the mouth done in pink, yellow, ivory, or black, lips registering temperatures from cool pink to molten orange. Or consider Fotozeby (Photosculptures, 1971), a sequence of black-and-white photographs of chewed wads of gum, each an abstract sculpture made by mouth, not by hand (but made as happenstance as Richard Serra’s Hand Catching Lead [1969]), alongside Szapocznikow’s very premeditated Rolls Royce II (1971), a miniature pink marble Rolls Royce Silver, complete with a winged gold phallus hood ornament (replacing the lady formally known as the “Spirit of Ecstasy”). The predicate work for Rolls Royce II was Szapocznikow’s initial proposal, My American Dream. Handwritten on a sheet of gridded notebook paper and illustrated with quick sketches, the proposal was “to blow up twice the size and in pink Portuguese marble, the convertible Rolls Royce. This work of object will be very expensive, completely useless, and a reflection of the god of supreme luxury. In other words a ‘complete’ work of art.”14 As trenchantly put by Ammer: “Chewing gum for the collectors! Miniature Rolls-Royces for everybody!”15 The latter is perhaps a nod to Moscow Conceptualism, and its equally opaque relationship to capitalism and Communism as neither-nor utopian solutions.16 Just as, for example, Komar and Melamid’s A Catalogue of Super Objects—Super Comfort for Super People (1977), My American Dream works as both parody and promotion, works, in a word, autoantonymically. Which is, finally, how I understood many of the pieces as being of a piece—not paradox, but antilogy.

Alina Szapocznikow, Piotr, 1972. Polyester resin, 80 3/4 × 17 11/16 × 13 inches. From the collection of the National Museum in Kraków. © The Estate of Alina Szapocznikow/ Piotr Stanislawski/ADAGP, Paris. Photographic Studio of the National Museum in Kraków.

When I heard Pollock’s talk on Szapocznikow at the Hammer, and her reading of Szapocznikow’s oeuvre through the scrim of historical/personal trauma,17 I was reminded of the Romanian poet Paul Celan, a camp survivor who primarily composed in German. In 1970, Celan drowned himself in the Seine. His poetry crumbled in the years before his suicide, turning from lyric to cryptic, because, it has been hypothesized, German proved the only adequately annihilative language in which to bear witness to annihilation. A zero-sum game, played against oneself. Inasmuch as poetry is fundamentally lingual, sculpture is comparably figural. Thus, to assert subjectivity via corporality is to assert the thing that undoes the thing; to assert this via ephemera (simply) underscores the point.18 When Rosalind Krauss considered Carl Andre’s Lever (1966), she noted that the fact the constituent firebricks had been originally made “for some other use within society at large” gave the objects “a natural opacity…the fire bricks remain obdurately external, as objects of use rather than vehicles of expression…. Mass production insures that each object will have an identical size and shape, allowing no hierarchical relationships among them.”19 When Szapocznikow deploys the repeated module, the unit is not the hard brick, but the soft belly.20 Ventres-coussins (Belly cushions, 1968) consists of five polyurethane foam casts, colored black, ochre, scarlet, and tan, of a woman’s plump stomach, the same plump stomach cast in Carrara marble in Petits ventres (Small Bellies, 1968) and colored copper-bronze and clustered like sea turtles beached on black lava in Grand Plage (Big Beach, 1968). By setting gentle rolls of fecund fat in stone or bronzing them like baby shoes, Szapocznikow makes the blunter functional argument about the role of industry in society, and the fatal consequences of individual fungibility. Put another way, hers is a messier, more ontic ontology.

Alina Szapocznikow, Untitled from Fotorzezby (Photosculptures), 1971/2007. Twenty gelatin silver prints. Original dimensions: 7 1/16 ×

9 7/16 inches and 9 7/16 × 7 1/16 inches. Collection UCLA Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, Hammer Museum. Purchased with funds provided by the Helga K. and Walter Oppenheimer Acquisition Fund. © The Estate of Alina Szapocznikow/ Piotr Stanislawski/ADAGP, Paris.

For the larger point here is that while there is great fun to be had in turning each piece into a prism of cathexes, there is a Cartesian stubbornness in all this parsing, as well as a facile assertion of the return of the repressed.

With Szapocznikow’s work, more than most, mode becomes medium: these movements through Pop, Surrealism, Nouveau Réalisme, etc., are all more or less happening simultaneously, and most within a five year span. So the reworking of motifs à la mode becomes not a symptom of Szapocznikow’s, but a historical sinthome of the time. As defined by Lacan, the sinthome is not a code to be interpreted; rather, it is the formulation function itself, the knotting together of Real, Imaginary, and Symbolic, the thing, in sum, that allows for jouissance. Jouissance, of course, is that which not only permits life, but demands it. Unpleasantly. For it should be remembered that although Szapocznikow’s biography is extreme, it is not unusually so. Death by disease and machine was a matter of course during the twentieth century, particularly in Europe, particularly in Eastern Europe, particularly among the Jews, particularly in Poland. Rather than romanticize another creative subject, we might turn to the perverted object: Szapocznikow is herself a partial explanation of European Pop, of Moscow Conceptualism, of Nouveau Réalisme, of Surrealism, etc. If history can only be endured, if the machine will win, if capitalism is, and Communism is, and both are what we all want and want not, and dreams only get what time has begot, then what? Or, better still, now what? What is left of any moment except to tempt the volcano to erupt? And so with Szapocznikow, sculpture’s logic is commensurate with all its material and a-material parts, including the problem of the body and the consolations of philosophy.

Medieval Christianity considered holy materiality in three cases:21 the first consisted of body or quasi-body relics, such as the blood of Christ or His holy foreskin. These were of the lowest material register because they were the actual stuff of the Divine. The second were those objects which had come into contact with the Spirit, and absorbed its miraculous properties through that transference, such as a piece of the One True Cross. The third case, the highest form of materiality, were those objects which became holy through the working of the Mystery itself—the object having no properties of or direct contact with the Divine, and yet being infused with Spirit. Such as the Host: “united in the supposito divino by the act of divinity.”22 Medieval iconography required that the icon similarly fuse matter and Spirit: a statue of Christ made of wood demonstrated His consumable mortality; one of gold, His eternal radiance.23 By this same token, Szapocznikow put the human body through the three material cases using the art movement that best suited that case: thus, the simultaneous production of the contact relic/Expressionistic/ jouissance 24 of Piotr and the manifestation of pure Spirit/Concept/Capital in Patinoire dans le cratere du Vesuve. And the terrible charter of Souvenir I.

In her most famous artist’s statement, Szapocznikow wrote: “Despite everything, I persist in trying to fix in resin the traces of our body: of all the manifestations of the ephemeral the human body is the most vulnerable, the only source of all joy, all suffering and all truth, because of its essential nudity, as inevitable as it is inadmissible on any conscious level.”25 Or, in the words of Antonin Artaud: “In our present state of degeneration it is through the skin that metaphysics must be made to re-enter our minds.”26

Vanessa Place is a writer, lawyer, and co-director of Les Figues Press.