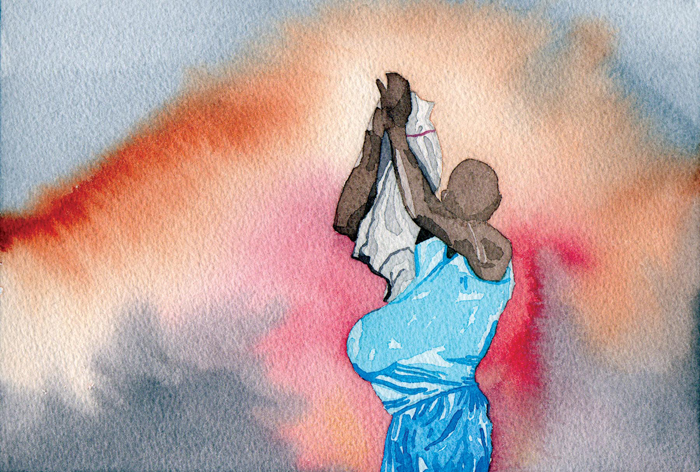

“Art versus Sport” is the name of Yrsa Roca Fannberg’s blog detailing the ups and downs of being an artist and Barcelona Futbol Club supporter. Entries alternate between meditations on the trials of experimental documentary filmmaking and the melodramas produced by loving perhaps the most storied side in the world. Illustrating this blog are Fannberg’s watercolor studies of life on the pitch–men in training, leaping into each others arms, throwing their bodies in the air, or glued to the ground in stupefied defeat.

It is tempting to think that Art and Sport sleep in separate beds. The discovery that one is at home in bohemia is often accompanied by parallel experiences of deep social isolation, of awkwardness and bullying, of being taunted for walking, running, or throwing “like a girl.” Maybe in your childhood, men and boys gathered in the living room around televised sport spectacle while you sprawled across your bedroom floor on your belly, pouring over magazine photos of Andy Warhol, Halston, and the superstars of Studio 54. For many of us in the arts, sports provided the childhood setting for our exile from normalcy. We tend to imagine these worlds as separate spheres, in which sport is fully masculine, and art is coded socially as effeminate and queer.

However, American art actually has a long history of defining itself through athletic imagery–through the identification of the (male) artist’s integrity with the heroic display of the male athletic body. The art world, in fact, has had its own bullies–intent on pushing the queers and the feminists off the field. This is in no small part because American art history has traditionally been the product of male writers writing about male artists, navigating a complex set of anxieties about the masculinity of both enterprises (art-making and art criticism).1

Thomas Eakins, Wrestlers, 1899. Oil on canvas, 48 3/8 x 60 in. Gift of Cecile C. Bartman and The Cecile and Fred Bartman Foundation. Photo © 2009 Museum Associates/LACMA.

Take the late-nineteenth-century painter Thomas Eakins’s fascination with rowers, swimmers, wrestlers and boxers–part of the artist’s interest in bodily realism, and also the avenue through which he produced his most compellingly homoerotic tableaux. These images are often animated by a nearly explicit homoerotic charge–as in Salutat (1898), which features a wrestler positioned with his back to both the viewer and to a male assistant whose gaze is unmistakably aimed at the athlete’s buttocks, or Wrestlers (1899), presently on view at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, in which two sinewy and nearly naked men grapple at the feet of two other men for whom this wrestling match has perhaps been staged. The athleticism of these images has functioned within art history as an alibi for their homoeroticism. Sadakichi Hartmann thus describes Eakins’s paintings as an inoculation against the effeminacy of the American art scene: “It is as refreshing as a whiff of the sea, to meet with such a rugged powerful personality. Eakins, like Whitman, sees beauty in everything…his pictures fimpress one by their dignity and unbridled masculine power.”2George Bellows’s paintings of men going at each other in the boxing ring translate homoerotic desire into homosocial aggression. These boxers, furthermore, offer the muscled spectacle around which homosocial bonds and identities articulate themselves among the watching fans in the crowd.3 In literature, iconic American writers such as Faulkner and Hemingway were drawn to baseball, and wove the sport into their fiction. The very idea of the “American artist” is shaped by the country’s love affair with the male athlete: what is Jackson Pollock’s “action painting” if not a transposition of the athletic gesture into the artist’s studio?4The more recent art critical romance with Matthew Barney’s days as a teenage football player and with his transposition of sport-theatricality into his practice is not the exception but the rule.

The rhetorical opposition of art and sport, in other words, is a narrative of convenience. It facilitates a critical game of fort-da in which the masculinity of the artist is eternally lost and rediscovered. From a queer feminist perspective, however, the gender dynamics of the art world and the sports world can be more similar than they are different. Women attempting to gain access in these arenas struggle with very similar problems, for example: the fight for equal participation,equal material support for their work, and just plain visibility. One might say there is at least a legal discourse supporting gender equity in sports, but where is the curatorial Title IX, guaranteeing women equal access to gallery walls? I asked this out loud in a museum, speaking on a panel about art and sports, and thought I could feel the institution shudder with horror at the idea.5

Rather than think here about masculinity lost and recovered by artists like Eakins or Barney, I want to consider how less authorized figures use sport as a point of entry into the visual field. As Fannberg’s images suggest, art and sport do intersect in at least one area–both have strongly utopian dimensions. Both are sites for fantasies about being “with” people. Bohemia and the locker room are both social spaces of desire, and spaces apart.

Deleuze spots the usefulness of the language of sport to art writing in his small book on the painter Francis Bacon. In responding to the encounter with “the athletic gesture” in Bacon’s paintings, the philosopher writes, “It is not I who attempt to escape from my body, it is the body that attempts to escape from itself.”6 This is to say that in the freakish extension of a hand or limb, Bacon does not show the attempt to transcend the body. The whole being of the body seems to be concentrated in the extension of a foot, in a swerve and dip of the shoulder to the left, in a leaping twist and turn of the head. The body here rather transforms itself as flesh–it crashes through the stories that tell you how to experience it, how to look at it, what to do with it. It becomes another kind of body. The body pulled through and recast by this moment, by this detail, is animated flesh.

Marriage, Soccer (from Fortunate Living Trilogy), 2004. Video still from single-channel, color video with sound, 7 min. Courtesy of the artists.

Queer sports spectacles stage fantasies in which the body becomes another body, and also play with what it means to be in a body, with others. Soccer (2004) features Wu Ingrid Tsang and Math Bass performing as the queer collaborative couple “Marriage.” Dressed in satin bodysuits with pads slipped over their knees and elbows, Tsang and Bass run in place while they rehearse the basic gestures that define soccer training. In this short video (the first of their Fortunate Living Trilogy) the two look like aliens belonging to a third or forth sex. Should we see them as boyish girls? Girlish boys? They have the ungainly and inchoate sexual presence peculiar to the teenage: an inherently queer failure to aspire to “adult” sexualities. They run in place and sweep the ground to their left and to their right as they shout: “touch left” and “touch right.” They jump in the air and jerk their heads as they shout: “head left” and “head right.” They each awkwardly juggle a ball with their feet, knees, and shoulders. They kick the balls against the wall. Sometimes they just sit. Or stretch. Or catch their breath. One seems slightly more competent than the other, but both seem unsure. They are clumsy, goofy, and shy in relation to each other–ill at ease, too, in and of themselves. They are sweet, and weird.

Marriage produced Soccer as a DVD insert for an issue of the ‘zine LTTR dedicated to the subject of “queer failure.” This weakly choreographed, lo-fi and oddball work gestures towards the specifically queer nature of the girls team–and towards what Judith Halberstam describes as the “utopian vision of a world of subcultural possibilities” associated with transgender experiments in gender ambiguity.7 That utopian impulse registers on the screen in gestures– in a shy look, a stolen glance, and in a slight discomfort with being caught in this setting, in which the two are both perpetually together and not. An odd tenderness develops between the two “players” as they rehearse these routines together, moving in parallel lines towards some form of unspoken intimacy. If I describe this work as queer it is not because it depicts girls wanting to be boys (they are far too gender ambiguous to be that for the viewer), nor because it shows two girls together (they are “together,” but they do not exactly interact with each other as a romantic couple). It is more nearly because it playfully draws out the erotics specific to queer fantasies about what it means to play together–and what it means to play together as boys. Soccer is a half-baked dream and an atypical sports text.

Where the male athlete figures prominently in American visual culture, images of female athletes are more rare. In fact, it has taken the transformation of U.S. sports culture initiated by Title IX to put the female athlete into circulation as a subject of representation. Popular takes on girls and sport tend to look like the story told in Bend it Like Beckham (Gurinder Chadha, 2002), or the more recent film Gracie (Davis Guggenheim, 2007). In both movies, a girl overcomes opposition to her desire to play with, or more nearly like, the boys. That opposition is animated in no small part by the challenges that her desires pose to what it means to be a girl. The full complexity of that challenge was an explicit part of the original story idea for Chadha’s international hit. Early in the film’s development, Chadha had imagined the central character Jess’s relationship to soccer as intertwined with her romantic involvement with Jules, another girl on the team. That story was re-written in the interest of maximizing the film’s marketability. Chadha decided to take on the issue of homophobia indirectly. Both characters were de-gayed, and the “lesbian” story took on a comic angle as Jules’s mother worried that her daughter might be a lesbian while the audience was reassured by the knowledge that the two girls were tied not by desire for each other, but by a rivalrous competition for the attentions of their male coach. The happy ending of the film has both girls headed to the U.S. on the athletic scholarships made possible by Title IX.

Gracie was produced by the sibling actors Andrew and Elisabeth Shue, and fictionalizes aspects of their childhood. In this film, the adored eldest son is a soccer star in a family of soccer fanatics. He and his sister (the only girl in a large brood) enjoy a special closeness around a shared love of the sport; the film opens with shots of the two passing a ball back and forth as they race home (in a loose, relaxed version of the sociability of Marriage’s video). Her interest in the sport is clearly tied to her affection for her brother and a desire to be “seen” by her father. But her passion and talent are invisible to everyone but her eldest brother, who dies in a car accident. Gracie mourns him by declaring a desire to train and try out for her brother’s high school team–to, in essence, become him. As the story unfolds in the late 1970s, there is no girl’s team at the school. Gracie uses the recently passed Title IX to force the coach to let her try out for the boys team. Like Bend It Like Beckham, characters express anxiety about Gracie’s sexuality, and the audience is reassured that although Gracie wants to be like a boy, this doesn’t mean that she doesn’t want to be liked by boys. The film is in many respects a traditional sports narrative. It is about an unlikely hero–an underdog–who overcomes the odds to help her team win the big game. It is a fantasy based on Elizabeth Shue’s own experiences as a girl who loved soccer and played it with her brothers. Unlike Gracie, however, Shue gave up the sport at a young age because in the 1970s, there was not even an imaginary space into which a girl might project an image of herself as a player. It is hard to project yourself into a fantastic space if you’ve never been given even the most rudimentary material with which to construct that fantasy. Gracie substitutes a story about participation for the darker reality in which the desire to participate is extinguished before it can even be articulated. (That decade, I should say, did offer two gold nuggets to inspire the queer girl athlete’s dream life–Billie Jean King’s 1972 match against Bobby Riggs, and Tatum O’Neal’s delicious turn in Bad News Bears [1976].)

The queer feminist sports text conjures up fantasies of community in which “girls” enjoy a different kind of visibility–and, crucially, a different kind of body. Perhaps the most iconic figure to indulge this kind of fantasy is Louisa May Alcott’s Jo March, the tomboy heroine of Little Women (1880). I think of Jo muttering “I wanna be a boy” a thousand times. I picture her slouching in the doorway, failing to sit still in her chair at the dinner table, and tossing her scandalously short hair as she expresses her impatience with everything. The closest the ur-tomboy of American fiction gets to actually saying “I wanna be a boy,” however, is probably the following declaration: “If I was a boy, we’d run away together, and have a capital time.”8She says this to her similarly gender ambiguous neighbour Laurie (a girlish boy who mirrors Jo’s boyish girl), as she indulges in a fantasy not of heterosexual coupledom, but of shared boyish adventure. Girls have crazy ideas about what boys do when they are together–and our attraction to team sports is in no small way fuelled by those queer notions.

Walt Whitman notes this gap between what girls think about what boys do when they are alone together and what boys think about what they do when they are alone together in “The Twenty-ninth Bather,” an often-cited section of “Song of Myself.”9 There, the poet spies on a woman who in turn spies on “twenty-eight young men” as they swim naked together. “All so friendly,” these young men enjoy an easy and unselfconscious freedom of which she can only dream. “Sitting stock still in [her] room,” looking through her window she dreams of the freedom and pleasure they enjoy. About midway through the poem, we find ourselves in the middle of her fantasy, swimming with her alongside these men and caressing their bodies. Whitman is clear that her participation must be secret, invisible, imaginary. “The rest did not see her,” he writes, as her dream-body swims alongside the others:

The young men float on their backs, their white bellies bulge

to the sun, they do not ask who seizes fast to them, They do not know who puffs and declines with pendant and bending arch,

They do not think whom they souse with spray.10

This part of “Song of Myself” is often cited in queer literary studies because Whitman identifies across gender in order to conjure an erotic intimacy between men. At first glance, it looks like a form of literary drag adopted by the poet in order to express forbidden homosexual desire, in which the woman acts as a “cover” for that which cannot be expressed. However, the geometry of this scene is even more complicated than this. In principle, another boy would be welcome; his presence would not disturb the pleasure of the scene. If this woman’s presence were to be discovered, however, the liquid erotics of the poem would evaporate. Were she to be seen, it would ruin everything. When the poet identifies with her, then, he identifies with both her desire to participate and her exclusion from participation–with the sense, too, that when she enters the water (itself a feminine space to which she belongs, but from which she has been banned), she makes something latent into something painfully visible. She produces sex (as a possibility, as difference) and takes (their) pleasure away. The artist Julie Tolentino has “(I Am) the 29th Bather” tattooed on the inside of her upper right arm. She hides lines of the poem in the setting for her performances, scrawled on strips of paper tucked out of the audience’s sight. Even as the poem seems to require the 29th bather’s invisibility, that invisibility gives Tolentino permission, under the cloak of parentheses, to enter the space of performance.

Most representations of men and sport focus on images like the one observed by the twenty-ninth bather–men and boys being men and boys together, unselfconscious and “in” their bodies. Such work takes on this scene without her critical engagement, without the “misrecognition” by which she imagines this kind of being-together as formed around an openly shared erotic. Such scenes are, of course, formed around a shared and psychoanalytically classic disavowal of that erotic connection. Take the affection that marks It’s Only a Game?: The Diary of a Professional Footballer, Eamon Dunphy’s memoir describing his last year playing for Millwall, the london professional soccer club infamous for the hooliganism of its fans:

When you share a job with somebody in football, a relationship develops between you, an under- standing that you do not have with players doing a totally different job. If you are just knocking a ball between you, on a training ground, a relationship develops between you. It’s a form of expression– you are communicating as much as if you are making love to somebody. If you take two players who work together in midfield, say, they will know each other through football as intimately as two lovers…It’s a very close relationship you build up when you are resolving problems together, trying to create situations together. It’s an unspoken relationship, but your movements speak, your game speaks… You don’t necessarily become closer in a social sense, but you develop a close unspoken understanding.11

The cover of Dunphy’s book carries an endorsement from novelist nick Hornsby, who declares “what sets Dunphy’s memoir apart is its honesty and lack of sentimentality.” This is a strange thing to say about both Dunphy’s memoir and soccer culture. I am not sure if it is possible to write an honest memoir about soccer without sentimentality, or at least without engaging its sentimental rituals. The emotional intensity of daytime soap operas pales in comparison with the operatic scale allotted to men’s feelings when the match of the day flickers onto the screen. Then you will see guys wrap their arms around each other in drunken tenderness. They will sing show tunes when their teams need encouragement (like “You’ll never Walk Alone,” a song from the musical Carousel, made famous by Doris Day and Judy Garland, and a Liverpool FC favorite when the chips are down). Their shoulders will heave as they weep at a momentous loss, and tears of joy fall from their cheeks when a last minute goal wins them an improbable victory. Their eyes mist over as they remember the glory days of Baggio, Garrincha, or Best, and they indulge in nostalgia for a time when the game seemed more honest, and the men more real.12 Hornsby’s assertion is more nearly a symptom of the common fantasy that men’s relationships to sport are somehow not sentimental, and that sports culture unfolds in a separate sphere from which all things womanly have been expelled. The Football Factory (Nick Love, 2004) thus opens with a gang of white working class “hooligans” beating down Tottenham fans they’ve smoked out of a local north london pub. A woman passing by screams at them, calling them out as a bunch of losers. The film’s protagonist stops to listen to her. As he does so, he takes a hard punch on the side of his head and is pulled back into the fray. In a voiceover, he muses on how he’d rather be brawling with these men than sitting at home in a sexless marriage. In this opening sequence women literally represent a dangerous distraction. Watching the men grapple with each other, it was hard to miss the way such scenes convert desire into hate, intimacy into violence and the way that sex (as possibility, as difference) is the point around which all this energy pivots.

If anything, as the above passage indicates, Dunphy is remarkably honest about the tenderness of his emotional attachments to the game and the men who play it with him. Elaborate protocols of reading and viewing manage how we see and experience these scenes of intimacy and belonging, even in art criticism (which you would think would be a more hospitable environment for the queer read than sports journalism). Douglas Gordon and Philippe Perrano’s Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait (2006), for example, is not unlike Dunphy’s memoir. Multiple cameras reproduce for us the experience of keeping company with the athlete in the middle of the arena during a football match. The film exploits what Eve Sedgwick calls the “privilege of unknowing” which allows us all to luxuriate in the spectacle of Zidane’s athleticism without, however, considering what it is that we are doing as our eyes linger over the crook of Zidane’s neck, as we admire the sweaty sheen of his skin, or contemplate the sublimity of the athlete’s weathered face.13Take Michael Fried’s remarkable appreciation of Zidane’s total absorption in the game:

Indeed, Zidane’s dazzling and unerring footwork, his astonishing control of the ball, his instantaneous decision making–all exemplify his seemingly unremitting focus on the game even as they combine to keep the viewer perceptually on edge, as does the sheer violence of his high-speed physical encounters with rival players as they try to strip him of the ball and vice versa… Another factor in all this is Zidane’s physiognomy, not just its leanness and toughness, emblematized by his balding, graying, closely cropped skull, but its basic impassiveness…which adds to the impression of an inner ferocity that, not at all paradoxically–think of the great stars of classic Westerns–could scarcely be more photogenic. (To say that the seventeen cameras “love” Zidane is an understatement.)14

Gordon and Parreno’s film is an intricately choreographed ballet of admiration and disavowal. This beautiful portrait reaches towards something like the experience of keeping company with Zidane while he plays this match, but it is also a deep mediation on how Zidane is visibly “produced” as a spectacle by cameras, by radio and by television broadcasts. It is marked by a nearly painful awareness of how hard it is to see through the spectacle of the game. (The moodiness of the film is amplified by Mogwai’s deeply melancholic soundtrack.) As we watch Zidane move around the field in the early minutes of the film (and the game) his thoughts stretch across the screen. The player recalls his boyhood attraction to evening football telecasts: “As a child, I had running commentary in my head when I was playing. It wasn’t really my own voice. It was the voice of Pierre Cangion, a television anchor from the 1970s. Every time I heard his voice, I would run towards the TV as close as I could get, for as long as I could. It wasn’t that his words were so important. But the tone, the accent, the atmosphere, was everything.” Even Zidane’s primary scene, in other words, is not the sensual immediacy of the action on field, but of the television broadcast.

Zidane takes not desire as its subject, but the mediation of desire–not our desire for the man, but our desire for the image of the man. Zidane explains, “I love the idea of transmitting the image of the player, of this guy on the field that brings happiness to those looking at him.”15 When he plays now for the cameras, he knows he is on that screen, pulling another little boy towards him. In fact, that little boy is me. It is us. I notice how stiffly he walks, and I think I know how he feels–the sport is brutal on your hips.

Rapidwands/Zizou312, Zidane—The Emotional Movie, 2008. Youtube screen shot. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=crwpz7b3oki, accessed march 19, 2009.

While Zidane clearly cites Fussball wie noch nie (Football as Never Before) (1971), Hellmuth Costard’s “real-time” portrait of George Best as he played a Manchester united match against Coventry (a nearly Warholian film in both its simplicity and its erotics), Zidane‘s closest contemporary cousin is actually the YouTube football homage. Hundreds (if not thousands) of homemade compositions set the highlights and lowlights of a player’s career to pop songs. “Zidane–The Emotional Movie,” for example, created by “rapidwands/zizou312” and posted by multiple users on YouTube in 2007, scores clips of Zidane on and off the pitch (many of these are pulled from Gordon’s film) to the Timbaland/One Republic pop song Apologize, which then fades into the Sick Puppies song All the Same. The opening lyrics of the latter, painfully sincere rock ballad are: “I don’t mind where you come from, as long as you come to me.” Other Zidane homages draw their music from Coldplay (“Beautiful World”), Madonna (“Love Tried to Welcome Me”), and even The Spice Girls (“Viva Forever”). At last check, videos set to Madonna and The Spice Girls had recorded well over 100,000 views each. There seems to be no irony in the use of pop ballads sung by women to score montages produced largely by male fans, celebrating male athletes. If anything, these songs (culled from European pop radio playlists) are perfect vehicles for communicating the powerful longings that undergird world soccer culture.16These texts–Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait and Zidane-The Emotional Movie–are formally linked by their explicit deployment of what James Tobias describes as “the musicality of time based media,” and by the movement of sentiment along the currents of popular music.17 But Gordon and Parreno’s film is a big budget and highbrow translation of a popular, wildly sentimental and decidedly lowbrow hobby–in which the “art” is produced by the disavowal of the popular.18Zidane elaborates on the spectacle which substitutes for the person, to allow for a viewing pleasure that might otherwise be too visibly queer. In doing so, the film raises the homosocial intensity of football culture by another factor–it repeats it, aestheticizes it, washes it clean, and makes it respectable. Yrsa Roca Fannberg’s watercolors recover this intensely visible and yet disavowed language of tenderness and passion–as well as its persistent citation of the feminine.

Yrsa Roca Fannberg, In Ecstasy (Full Bloom), 2007. Watercolor on paper, 31 x 23 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Yrsa Roca Fannberg, Rebirth, 2009. Watercolor on paper, 18 x 26 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

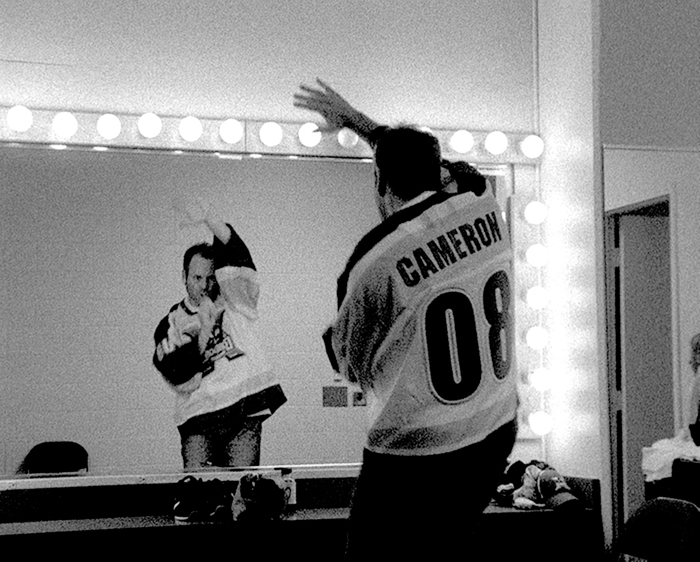

When Jo imagines the “capital time” she might have as a boy with other boys, she imagines a world closer to the fantasy of the 29th bather than the actual experience of being one of those 28 young men. The reality of those settings is quite far from Whitman’s queer idyll, and even farther from the gorgeous spectacle of Zidane. Contrarily, Adria Julia explores the darker side of this world in his installation La Reunion (2008). This moody, black-and-white projection opens with a man in front of a mirror in a spare dressing room dancing like a boxer before a match. He pulls a large hockey jersey over his head and slips on his headphones. The speed of the film is slow; he bounces up and down, back and forth–jumping around to music we can’t hear. He moves across the room, lunging towards his mirror image and pulling back towards the camera. He is getting ready to perform. The slow speed makes his body seems heavy as he swings it around the room. When he steps into the arena, he steps not onto the ice but into the stands of the dilapidated Reunion Arena, home to Dallas’s hockey games. We watch him lead the largely white, working- class audience through cheers, shouts, and rounds of clapping. He is a plant, a spectator paid to supplement the crowd’s waning enthusiasm. Cut into this strange performance are shots of the empty arena and audio lifted from a Dallas museum, in which cliched country guitar cords animate a historical narrative describing the nineteenth-century utopian commune after which Reunion Arena and Julia’s installation are named. The Dallas commune was inspired by the writings of French utopian philosopher Charles Fourier who, it should be noted, is often credited with having coined the word “feminism” in the process of imagining a social world defined by gender equity.

Adrià Julià, La Réunion, 2008. Video installation; 13 minutes, 34 seconds. Courtesy of the artist.

Adrià Julià, La Réunion, 2008. Video installation; 13 minutes, 34 seconds. Courtesy of the artist.

Zidane is a successful spectacle (an image in which we are interested, an image for which there is an audience, and an image that we are entitled to look at and enjoy). It is a hyper-spectacle in which the thrill of the enjoyment on offer is derived from the awareness that we, as audience, are part of a global spectacle. We are happy spectators to our own spectatorship. Julia’s installation, on the other hand, offers a spectacle that is not at all spectacular: a minor league hockey game set in a decaying arena that was itself built on the grounds of failed utopian community. In La Reunion, we are looking at communal and generational collapse, at collective failure, and the gap between the imagined and the real.

The ideological limits that organize mainstream representations of the female athletic body surface more explicitly in Stand Your Ground, Moira Lovell’s 2008 installation of a series of portraits of the women who play for The Doncaster Rover Belles. The Belles are one of the older teams in English women’s football. Women working the stands selling programs for the local professional men’s team, the Doncaster Rovers, founded the Belles in 1969. (Women fans of the men’s clubs who wanted to play started nearly all of the most prominent women’s teams in the U.K.) In these portraits, the Belles do not meet the camera with the obligatory disarming smile asked of women athletes on those anomalous days when the media takes interest. nor are these traditional team photos presenting the united front arranged in tidy rows on the pitch, bodying forth the team’s identity en masse. As much as the game is marked in England as a working-class sport, it is even more deeply coded as masculine, thanks largely to the England Football Association’s fifty-year ban of women from its fields. That act was explicitly intended to kill off the popular women’s game in the 1920s, not only because the women who played it were considered unseemly–cigarette smoking, swearing, and hard playing (and plainly gay)–but because those women had politically organized to support striking workers.19 (The English FA ban became the model for similar bans enacted around the world.) Because of this history and the sports culture that it created, in those countries where women’s soccer was in essence outlawed (including England, Germany, Spain, and Brazil), a woman’s uniform feels like a black leather motorcycle jacket. Even as it signifies membership in a team, a collective identity, it also signals a form of rebellion. In England, in other words, you don’t need to wear Tsang’s purple satin body suit to feel like a gender freak–you can just wear your training outfit.

Moira Lovell, Stand Your Ground (2008) Installation view (Top row, left to right: Liz and John, John and Vicky, Sophie and John; Bottom row, left to right: John and Precious, John and Veronica, John and Ness), 2008. Commissioned by Pavilion. Courtesy of the artist.

Looking at these images, I am reminded of how important the game is to the women who play it, in no small part because it radicalizes one’s experience of the body. It is one thing to see the body transformed in Bacon’s painting. It is another to feel one’s own body transformed within and by the athletic gesture itself. As much as women are taught to have (or that they should have) a strategic relationship to their looks, we aren’t always encouraged to develop physical awareness of the embodied self–the kind of awareness that is paradoxically won when self-consciousness is lost. But the spaces in which that self-awareness looks and feels natural are somewhere else. They are not on television, not in the newspapers, and not in the movie theaters. And they are not here, in these photographs of an antiseptic locker room. Here we intrude, and the players stand in formation against us.

Lovell pairs each of the Belles individually with the team’s coach. In this juxtaposition we are invited to see difference–in gender, surely, and in age and authority. But when the English FA banned women from its pitches, it also banned male FA members from supporting the women’s game as referees, linesmen, etc. The ban wasn’t just an attempt to regulate women footballers out of existence. It was an attempt to ban the re-wiring of men and women’s relationship to each other that women’s athletics invariably brings about. It was an attempt to undo the queering effects of the women’s game on gender and sexuality, on the bodies on and off the field. Lovell’s images are anxious and claustrophobic when compared with traditional portraits of footballers. Instead of picturing the athletes outdoors, on the field, and in play, in Lovell’s photographs, players and their manager are instead backed into a locker room corner. In place of grass we have antiseptic tile. In place of open sky, we have a ceiling hanging low above their heads. In place of movement we have a stance.

The coupling of player and manager draws attention to the biggest threat to mainstream visual culture posed by women’s football: seeing lesbians everywhere. Mainstream representations of the female athlete are muted, carefully edited, and constrained. Commentators step over references to their personal lives. A press release announcing the new U.S. Women’s Professional Soccer League uniforms uses the word “feminine” twice–as if to reassure people that these women will look like women. When the female athlete steps into the public arena, she is asked to straighten herself out. Or, she is straightened out by the camera. Out of the public’s eye, however, on Sunday afternoons at Hackney Marshes (where my former London teammates play), you can actually see something like what Whitman saw, and what Jo March imagined she might enjoy: a rowdy bunch of players forgetting themselves, and finding themselves in a sexy dream having a “capital time” enjoying a deeply embodied form of communion.

Moira Lovell, John and Precious (Precious Hamilton, 21, Centre Midfield, 1 year with the Doncaster Rover Belles at the time of the photograph), 2008. C-Print; 70 x 60cm. Commissioned by Pavilion. Courtesy of the artist.

In representations of men at play, intensely homoerotic scenes flourish under our noses but only with the promise we not “see” the erotic currents that animate them. The “obviousness” of the queerness of women playing together–their butchness, their boyishness–means that we are barely allowed to see them play at all. Lovell’s portraits register the ambivalence with which the female athlete approaches the public sphere. They manifest the pressure to “straighten” the female athlete, to reassure the spectator by forcing us to read these women via the mediating presence of the manager. This scenario isolates each from the other, triangulates them and us through the male managerial body, and edges the game, too, out of the frame.

Take one of these portraits and perhaps you see a couple. look at the installation series, however, and the male body becomes a superfluous and awkward presence nearly as out of place as Whitman’s 29th bather. The mediation of the spectacle of the men’s game seems to provide the artist-fan a distance that gives him permission to adore his subject. Without that visual archive, without the spectacle of the spectacle filtering us from them, the task of representing the female athlete is more charged, and more overdetermined. Zidane can act like the cameras aren’t there. His self absorption–in himself as athletic spectacle–lets him get on with his work, and lets you look at him without the particular discomfort of fearing that somehow he might look back, as if he knew what you wanted. In the world captured by Lovell’s camera, when the lens is trained on her, the female athlete doesn’t move. These women do not have the luxury of disavowing the camera’s presence and all that it implies. The spectator is an unwelcome presence in this space, in much the same way that these women are unwelcome within the deeply patriarchal and homophobic spaces of English football. It is as if these women–at least these women as I want to see them–are really somewhere else. As athletes, their field of play is off the visual record, and, perhaps, on another planet.

Jennifer Doyle is an Associate Professor of English at the University of California Riverside. She is the author of Sex Objects: Art and the Dialectics of Desire (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006) and is finishing a book on difficulty, emotion, and contemporary art (forthcoming from Duke University Press). The preceding essay began as a short essay on Moira Lovell’s photographs in New Works: Pavilion Commissions 2008 (Leeds, 2008), and is part of Uncoupled, a work in progress exploring forms of intimacy and belonging outside the space of the romantic couple. Doyle writes From A Left Wing (http://fromaleftwing.blogspot.com), a feminist blog about soccer which she shares through the website Women Talk Sports (http://womentalksports.com). She is the treasurer of the Union Football league in downtown Los Angeles. This essay is dedicated to the Hackney Women’s Football Club, for whom she proudly played left back on the reserves squad in 2007-2008.