Few things seem more characteristically interesting to Americans than the Second World War, the Holocaust, and the German response to them. You would have to look far and wide for better historical examples of such a proprietary interest. Imagine India, for example, fixating on the role of Italy in the same period, or picture the Japanese taking an interest in the Partition of British India and its consequences. The cause is less geographical than cultural. Germany and the United States have a far more complex relationship than the Japanese to the Indians or the Indians to the Italians. Ethnically the Germans are as large a part of the early white immigrants to the US as the English, but looking further one finds continuity between the bourgeois liberal culture of Germany, the UK, and the US. At some point every child of a German family in postwar America was asked, “What did your daddy do in the war?” I was one of them, so I know. Whatever the answer to that question was, its context overrode everything. Imagine Hollywood without war films, or without the Holocaust. Is it mere coincidence that there are four times as many films about the Second World War than about Vietnam, or that half the major films about the Holocaust are American?

One compelling area in which we might examine the nature of this relationship is in LACMA’s historic exhibition The Art of Two Germanys/ Cold War Cultures, which presents art from the two Germanys from 1945 to the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. Co-curated with Eckhart Gillen of Kulturprojekte Berlin, this is the third of curator Stephanie Barron’s magisterial trio of German shows. The first was “Degenerate Art”: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany (1991), which assembled many of the Modernist artworks suppressed by the Nazis and framed them in an overarching context for the first time. The second was Exiles and Émigrés: The Flight of European Artists from Hitler (1997), which traced the migration of artists within Europe and to the United States and chronicled their reception. The Art of Two Germanys completes the set and like its predecessors is travelling to Germany. What is remarkable about all three of these shows is that while Exiles and Émigrés might be considered a natural for an American museum, the other two present major retrospectives on German subject matter in a way that German institutions still have not done.

The clichés against which LACMA’s exhibition must play are familiar to us: the triumph of the progressive art of West Germany over the oppressive, state-controlled socialist model of its counterpart. According to this tale, East Germany exercised a repressive grip over its artists that echoes in style, if not in scale, what the National Socialists did to their artists a generation earlier, while the “free” artists of the West return to aesthetics and content suppressed by the Nazis, both redeeming the Modernist project and taking it to the next stage. Like many clichés, these contain elements of truth, but the LACMA show manages to draw out contrasting narratives that, while not overturning the dominant one, give it more complexity.

Werner Heldt, Tür (Door), c. 1946. Crayon and mixed media on wooden door, 59 5/8 x 23 in. Berlinische Galerie, Landesmuseum FüR Modern Kunst, Fotografie und Architektur. ©2009 Werner Heldt Estate/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Photo courtesy Berlinische Galerie, Landesmuseum fur Modern Kunst, Fotografie und Architektur. Photo: Hermann Kiessling.

Entering The Art of Two Germanys is like arriving at a wake. The first of four chronological sections, the room of work from 1945 to 1949 is funereal in aspect. In muted tones, with dead nature, collapsed architecture and huddled or anguished figures, little about the devastation of the immediate post-war years is left to the imagination. Two images of doors, one a collage by Werner Heldt, Door (1946), and the other a painting by Jeanne Mammen, Door to Nothingness (1945), perhaps best evoke the impossibility of expressing this moment. Both doors are closed, as if to open them would be unthinkable. Few of the artist’s names here register from earlier or later periods, and even an oil painting of grieving women by the great Hannah Höch fails to attain the power of her photomontages from the 1920s and 1930s. The overall effect of this section echoes melancholic thrift store art. Though it succeeds in conveying the melancholy, anguish and existential angst of the time, virtually none of the work seems to find an adequate form for its content—we receive only the traumatized muteness of the survivors.

The second section, work from the 1950s, quickly changes in tone and begins to reflect the ideological divisions between socialism and capitalism. The social realist work from East Germany is ideological, of course, but also charming and painterly. It calls our attention to how rarely workers are depicted anywhere but in documentary photography and film; perhaps it is only possible for us to see this in these paintings because state socialism now seems extinct. Oddly, the abstract work from West Germany often employs similar palettes but to an opposite effect: because of its lack of figuration, the work was read as critical and anti-Nazi. It also happened to fit snugly within international Western trends, and to the curator’s credit, its placement near the socialist realism offers us the chance to read the abstract work as also ideological, though in different terms.

A few pieces stand out from the selection of 1950s work, including two paintings by West German Konrad Klapheck—one of a typewriter, The Will to Power (1959), and the other of a washing machine, The Offended Bride (1957). Clean and precise almost to the point of abstraction, these take on both the ordinary world in way we recognize from socialist realism, but through their monumentalizing of the technological objects of consumer culture, they also yield an implicit critique of West Germany at the height of its postwar Wirtschaftswunder, or economic miracle. Nearby are East German Hermann Glöckner’s group of constructivist objects made from household materials such as paper clips, eyeglasses, newspaper, cardboard, rubber bands and a sliced tin coffee pot. Exhibited for the first time in the United States, these Table Works (1960-1970) are both self-contained pieces and studies for larger and apparently unmade sculptures, all of which were kept hidden in his atelier. Objective and ordinary, yet in dialogue with form and abstraction, this work can neither be read as championing nor critiquing socialist principles. The pieces are concentrated and expressive, hinting at the world in which they arose, yet a world in which they could never be displayed.

Another grouping of compelling pieces from the 1950s are two sets of critical photographs. Several images of everyday life in the Rhineland by Chargesheimer interrogate the West German myth of prosperity and good fortune, with new housing tracts barely concealing their staleness and sterility. In a striking parallel, a sober group of black-and-white photographs by East Germans Ursula Arnold and Arno Fischer examine life in the two Berlins and signal their distance from the politics and aesthetics of both sides. Yet like the work of Glöckner, these images did not appear in public until after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

The largest portion of Art of Two Germanys is dedicated to the 1960s and 1970s, whose dynamism is wisely not divided in two parts by the curators. Barely visible on the international scene in the 1950s, German art went from red hot in the 1960s to white hot by 1980. This section of the show charts this dynamic leap, and here the viewer finds the artists most identified with postwar Germany: Anselm Kiefer, Joseph Beuys, Sigmar Polke, Wolf Vostell, Eva Hesse, and Gerhard Richter. As elsewhere in this time, form explodes, with two-dimensional work supplanted by eclectic sculptures, installation pieces, and video art. But particularly notable is the explosion in content, with snarky critical work among the sternly introspective, the light and the comical. Dieter Roth’s pungent Chocolate Lion Tower (1968-69), a process sculpture, dominates the room with the smell of decaying cast chocolate lions collected in the hundreds. They appear on a towering rack, at once a comment on the excess of consumerism and the status of the art object, anticipating Jeff Koons’s banal balloon animals a generation later. Likewise Roth’s Literature Sausage (1969), made of shredded books mixed with spices and lard and stuffed into sausage casings, offers a witty commentary on both the classics of bourgeois German literature and the German fervor for making sausages from anything.

Wolf Vostell, Hommage á Lidice, 1967. Mixed media, 43 1/2 x 47 1/4 x 7 7/8 in. Památnik Lidice/Lidice Memorial. © 2008 Estate of Wolf Vostell/Artists Rights Society, New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Photo © Památnik Lidice/Lidice Memorial.

Vibrant critiques of consumer capitalism are set cheek by jowl with Fluxus pieces and performance documents. Among the standouts is Vostell’s 1968 Lipstick Bomber, a painting of a military bomber dropping sticks of lipstick onto the world below, as if wartime devastation could be resolved with women’s makeup. Günther Uecker’s TV on Table (1963) bristles with handmade nails on its top and sides, and we find it a few steps from Joseph Beuys’s film Felt TV (1970), in which he encloses himself and the television set with handmade felt boxes. Here I overheard one visitor saying, “You know, Germany has come a long, long, long way.”

Günther Uecker, TV auf Tisch (TV on table), 1963. Wood, TV, nails, glue; 47 1/4 x 39 3/8 in. Skulpturenmuseum Glaskasten Marl, Germany. © 2009 GüNther Uecker/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

The dark heart of The Art of Two Germanys is in its largest room and it emerged historically at the moment German artists began reckoning with the national guilt over the past, what in German is called Vergangenheitsbewältigung. The Eichmann trial in Israel in 1963 and the Auschwitz trials in Frankfurt two years later spurred a new wave of politicization as silence within Germany about the Nazi past was finally broken. Anticipating this resurgence of angst was Vostell’s Black Room Cycle (1958), which is represented here by Auschwitz-Floodlight 568. A sticky, black-painted assemblage of an inverted floodlight, barbed wire, electronic parts, and what seem to be bones and hair confronts the viewer with what must have been the unspeakable. Once you look, your gaze is stuck, but what you see is not entirely clear and yields no easy answers.

Anselm Kiefer, Deutschlands Geisteshelden (Germany’s Spiritual Heroes), 1973. Oil and charcoal on burlap, mounted on canvas; 120 7/8 x 268 1/2 in. The Broad Art Foundation, Santa Monica. © 2009 Anselm Kiefer. Photo courtesy the broad art foundation, Photo: Douglas M. Parker Studio, Los Angeles.

Anselm Kiefer’s enormous painting Germany’s Spiritual Heroes (1973) dominates this room much as it dominated the American perception of West German art through the 1980s. It depicts an empty wooden hall of crudely painted beams with spindly burning torches over the names of German cultural heroes some associated with fascist ideology and some not. At best, one might argue that the work’s facile content is set off by its enormous scale, which guarantees it can only be shown in a museum. Both pathetic and heroic, the painting’s emphatic broad strokes leave us without a clear or singular reading and so seem ready-made for an international

marketplace. Bombastic and ugly, its presence speaks as much to what German artists were doing as to what the American and international art audiences desired to see: repentance and disavowal of a certain heroic German tradition. What may once have been unspeakable—the relation of German high culture to the most brutal chapter of its history—becomes a pat commodity.

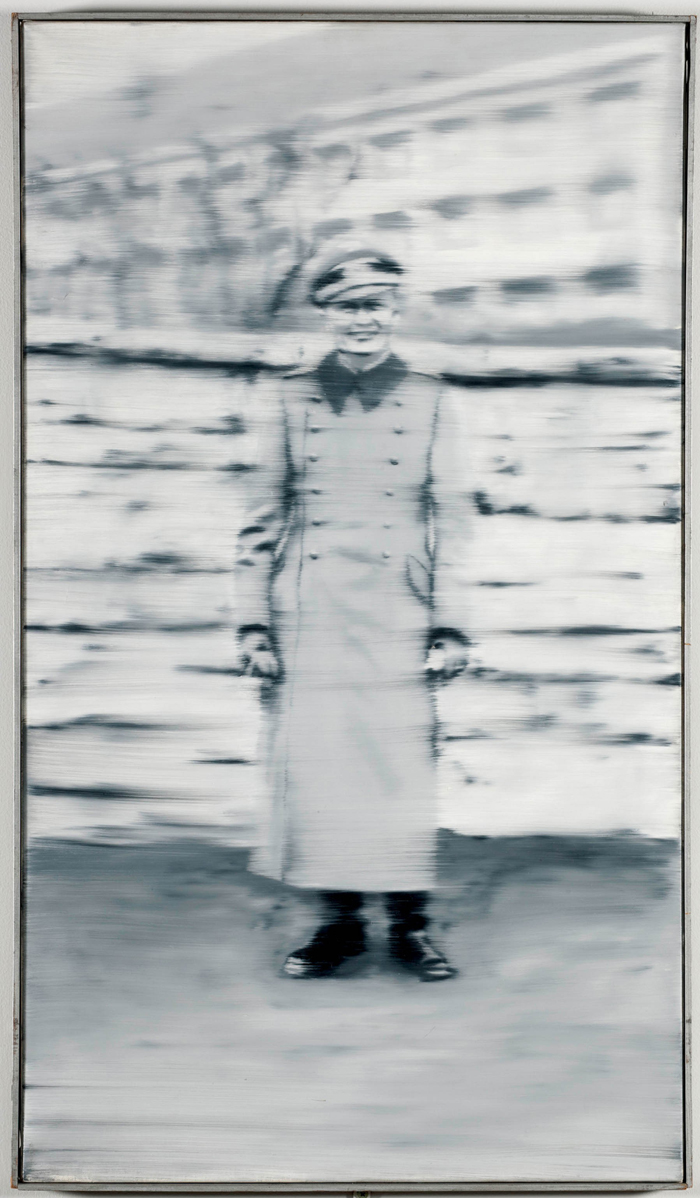

In comparison, the three famous paintings by Gerhard Richter in this room are studies in restraint and complex, layered analysis. All are adapted from old photographs; the most familiar one is 1965’s Uncle Rudi. Richter’s uncle, in his Nazi uniform, represents the sort of ordinary Nazi that had finally been put on trial in the 1960s. The painting is in beautiful gray tones, the paint blurred upwards as if by a Xerox machine or television broadcast. It plays on the familiar and the familial, on the likelihood that every German family had a Nazi somewhere, and on the blurry persistence of an avuncular banality of evil. Fascism too had an ordinary side, and perhaps this remains with more persistence than its evil incarnations. The hauntedness of this image is in part technological—in the frisson between painting and xerography or television broadcast, and Richter’s uncanny ability to keep all those references in tension—but beyond this what haunts us about Uncle Rudi is its banality.

Gerhard Richter, Onkel Rudi (Uncle Rudi), 1965. Oil on canvas; 34 1/4 x 19 5/8 in. Památnik Lidice/Lidice Memorial. © 2009 Gerhard Richter, Courtesy Of Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo courtesy Památnik Lidice/Lidice Memorial.

Beuys is the other unavoidable figure of this period, and he looms as both hero and trickster in the exhibition. His work is in a long, narrow corridor we pass through after the heroic mumbo jumbo of Kiefer’s barren hall. The curators capture Beuys’s various modes or moods, beginning with the impeccable minimalism of his familiar felt suit and Sled (1969), a sort of minimal survival kit packed with felt blankets, belts, a flashlight, fat and rope. Reflecting the moral seriousness of his work as well as echoing his own narrative of being shot down in the war and surviving hardship and bitter cold, the sled is a meditation on what is necessary in order to persist in the most intolerable of times and places. After this we find the political Beuys in Sweeping Up (1972), a performance in which Beuys swept the streets after a left-wing May Day demonstration with a red broom—by its coloring a symbol of the socialist-leaning left. Yet while implying the need to clean the nation’s public space, the piece seems to signal that neither side is ideologically unblemished. Here I overheard another visitor muttering, “This is when Germany gets really interesting.”

At the end of the hall is the familiar Warhol-like silkscreen of Beuys in his hat, white shirt, and tight jeans, a sort of beatnik hero looking far younger than his fifty years in 1972. Almost the opposite spirit of his Sled piece, this silkscreen testifies to the care with which Beuys constructed his own image, playing the role of a certain kind of artist that has parallels to the very different role Warhol played in his world. Anti-hero, rebel and loner, Beuys becomes a kind of thinking man’s Warhol, a model for a generation of German artists far different than the affected affectlessness of his American counterpart. We must conjecture on whose behalf this image was constructed—the international art scene or the West German one, in which Beuys had already become recognized as a master through his work and especially his teaching?

Installation view, Art of Two Germanys/Cold War Cultures, January 25–April 19, 2009. Photo © 2009 Museum Associates/LACMA.

After this intense focusing on themes and historical problems, The Art of Two Germanys becomes more unwieldy and strains the capacity of its audience to process the various divergences and transformations of postwar German art. Rather than a failing, one might see this as a deliberate strategy for laying out a set of problematics without a neat resolution. The narrative of East and West drops away for large parts of the section devoted to the ‘70s and ‘80s, though much is made of the small and charming case of the friendship between two painters with shared sensibilities—the West German Jörg Immendorff and A.R. Penck, an East German who left the East in 1980. Communicating and meeting throughout the late 1970s, the friendship of the two artists is manifested in Immendorff’s Café Deutschland series, set in a busy nightclub that serves as an imaginary site for the two friends to meet—a meeting between East and West as well as Germany’s past and present. While worthy in intent, the work falls short of the more nuanced if unresolved work that precedes it, and ultimately seems naïve.

In the 1980s the swastika begins to appear broadly in German art, after having been forbidden in public for forty years. The strongest example here is in Olaf Metzel’s Turk Flat—Compensation DM 12,000 (or nearest offer) (1982), photographs and performance documents of the artist’s renting of an apartment from which a Turkish family had been evicted. Demolishing the furniture he found abandoned there, he mounted an enormous carved relief of a swastika onto the living room wall, and then posted an ad for the flat as a Türkenwohnung (Turkish home) in two daily newspapers. With its archeological echoes, the image of the carved plaster swastika posed a question about the persistence of Nazi policies into the 1980s. Despite the swastika’s undeniable power to shock the viewer, it quickly becomes shorthand for a historical question that in many ways was explored more subtly when the question of German national guilt was harder to articulate in an open way.

America’s fascination with “the German question” takes precise focus with the inclusion of German-born, American citizen Hans Haacke. Here the influential installation artist is represented by one of his most graphic pieces, Oil Painting: Homage to Marcel Broodthaers (1982), a piece that in its two forms addresses both America and Germany. Installed in a room to itself at LACMA, a red carpet and velvet-roped stanchions link a grandiose oil painting of Ronald Reagan to a photomural opposite of a large anti-nuclear protest in New York. When shown in Germany, the New York mural is replaced by a photomural of a protest in Bonn against Reagan’s proposal to deploy nuclear missiles in West Germany. The two versions of this piece make an explicit set of connections between German and American politics; the authority of the presidential portrait and the stylization of the red carpet and velvet rope echo the pageantry of both fascist art and demonstrations. In a far more troubling way, the installation links the past and the present with Reagan’s reactionary posturing and its consequences in both countries. The presence of Haacke’s installation makes explicit not only the relation between American interest in questions about German history, fascism, and national guilt, but also the structural parallels between reactionary political movements across time and space.

Concentrating on the 1980s, the last section of the Art of Two Germanys starts to reflect not just a gaze outward among German artists, but also the failures of 1960s and ‘70s leftist politics. This is not to say the show loses its specificity: among the most memorable pieces that resonate in the present is Jürgen Klauke’s Faces (1972-2000), which here includes 65 C-prints from the 96-part work mounted in a grid. Variously blurred, from cloudy to nearly unintelligible, the images are all masked faces re-photographed from newspapers beginning with the faces of the masked terrorists at the 1972 Munich Olympics. Of great variety, with stockings, caps, scarves, bags, veils, fabric, and ski-masks, the images sometimes allude to nationality—Arab, Afghan, or Irishman—but always balance marks of difference against the power of official surveillance. In the context of German history, from the collapse of democracy under fascism to the brutal repression of the student movements of the 1970s by a “democratic” government, Klauke’s piece asks what it means to be a terrorist and where the limits of the state are to be found. The faces, mostly young and largely middle eastern and Turkish in affect, are unable to speak for themselves and serve as a site for the viewer’s historical and political imagination.

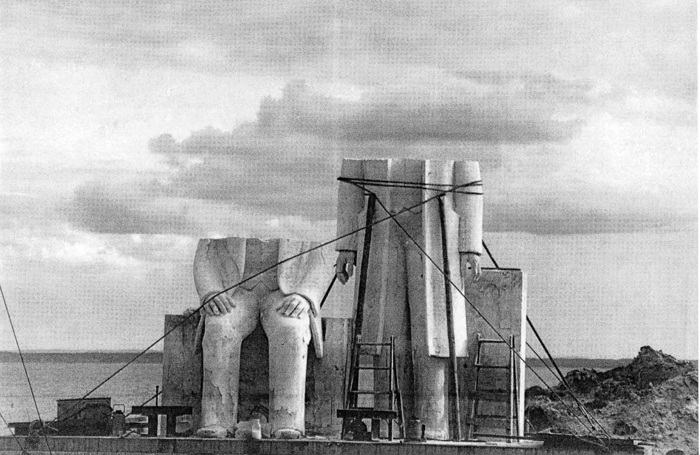

Sibylle Bergemann, Ohne Titel (Gummlin) (Untitled [Gummlin]), 1984; From the series Das Denkmal (a monument), 1975–86. Gelatin silver print, 19 5/8 x 25 5/8 in. Collection Sibylle Bergemann. © 2009 Sibylle Bergemann.

Hermann Glöckner, Installation view at LACMA, 2008. Mixed media, dimensions variable. Private collection, Dresden. © Estate of Hermann Glöckner/ 2008 Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Photo © 2008 Museum Associates/ LACMA.

While impossible to resolve, one of the strong notes near the end of the exhibition arises in Gerhard Richter’s iconic November canvas painted as the Berlin Wall was falling in 1989. While not representational, November is neither entirely abstract. Dominated by streaked grays, browns, and greens, it appears somewhere between a large steel gate and a screen of video noise. The painting’s intangible message is not especially hopeful, yet a bright band of color breaks through the grey. If the Art of Two Germanys traces an enormous road that divides in two, then winds around a giant island to come together again at its end, its terminus is far less clear than its origin.

Gerhard Richter, November, 1989. Oil on canvas, diptych: 126 x 73 3/4 in. Each panel. Saint Louis Art Museum, funds givern by Dr. and Mrs. Alvin R. Frank and The Pulitzer Publishing Foundation. © Gerhard Richter, Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo courtesy Saint Louis Art Museum.

Perhaps the impossibility of resolution lies in this imaginary blank island, easily symbolized by the Berlin Wall and yet escaping all representation. The invariable question—how could such a liberal, enlightened and modern nation let loose such terrors on itself and the world—remains unanswerable. Speaking now as an American, I wonder if the greatest moral impact of the art of the Cold War Germanys arises as much from the scale of the history it seeks to address as from the range of the aesthetic strategies deployed by its artists. What other nation’s art of the same time can threaten to dwarf our own? Our collective fascination with this period and its art may stem from our suspicion that irrationalism is never very far from any enlightened nation, even the United States. Rather than anxious disavowal or the defensively complaisant “America is not Germany,” our fascination may come from the proximity of our identifications. The scale of our interest in German art perhaps reminds us that what we like to call the American century looked for a while as if it might be the German century. And what would our art have become had “American” values not prevailed?

Matias Viegener is a member of Fallen Fruit. He teaches at CalArts, and lives and works in Los Angeles.