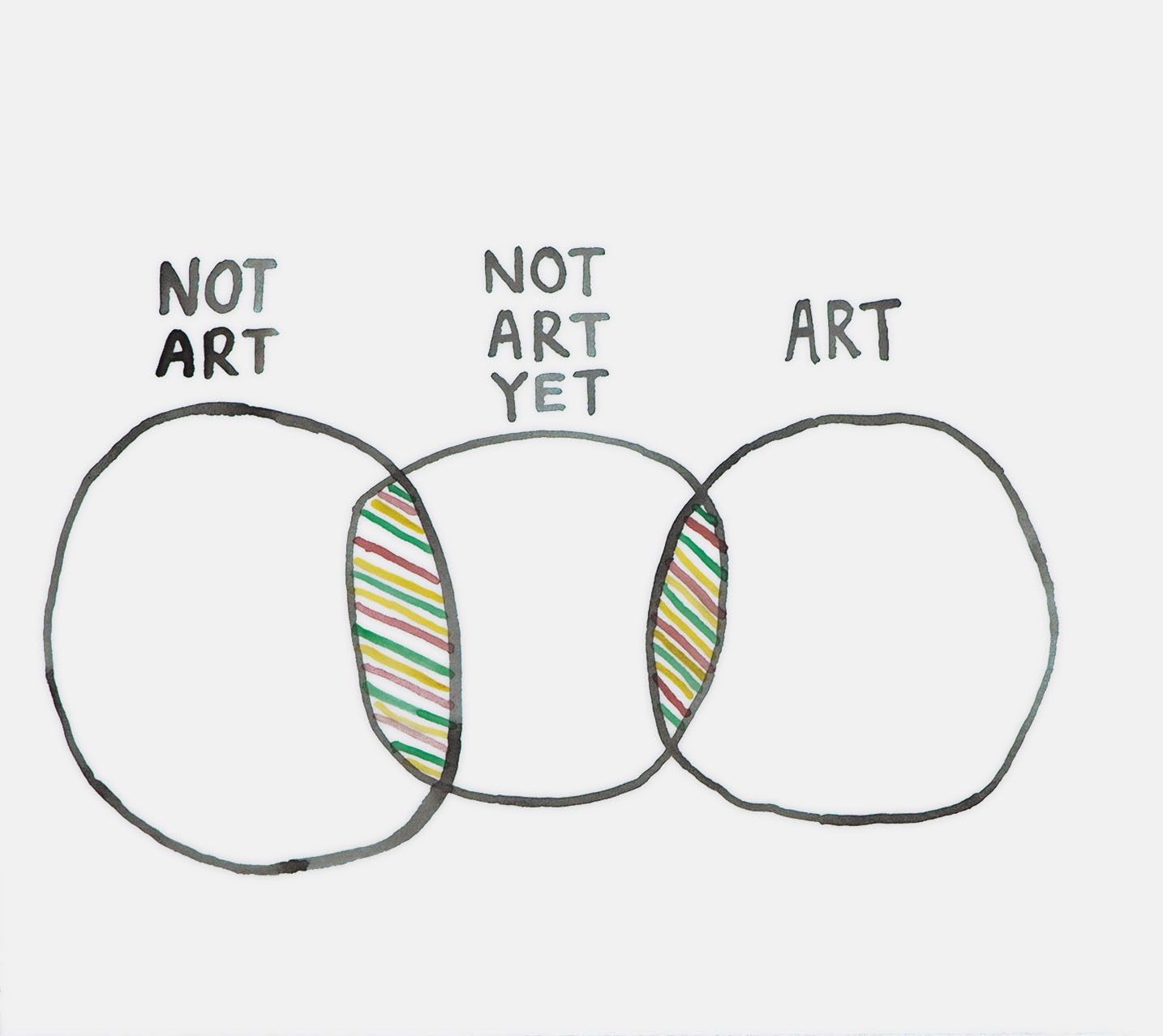

John Ziqiang Wu, An Art Chart Drawing, 2017, watercolor on paper, 6¼ x 6 ¾ in. Courtesy of the artist.

In John Ziqiang Wu’s An Art Chart Drawing (2017), a Venn diagram illustrates a seemingly logical relation between three categories: 1) “NOT ART,” 2) “NOT ART YET,” and 3) “ART.” The purpose of a Venn diagram is to provide a visual illustration that represents the similarities and differences between two or more concepts. One would expect “ART” to occupy the center of Wu’s schema and represent a segment where differing concepts produce commonality. But Wu knows that “ART” cannot be designated between oppositional concepts that could easily determine a resolution; therefore, “ART” is situated on the margins of his diagram. It is through this illustration that I became interested in Wu’s art practice of drawing, painting, installation, performance, and storytelling, which are the results of his observations of the actual overlap between his institutional and personal experiences. The overlapping condition of Wu’s interests extends his practice from the studio to his lived experiences—as a former student, an immigrant from China, a parent, and a teacher—as he performs the duties specific to his relationships to various institutions. Wu recently completed an artist’s residency at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, where he undertook day-long internships with every department within the museum. He was a visiting artist at California State University (CSU) Bakersfield, where he worked with undergraduate students towards an exhibition. And he founded the Learning Art and Art Learning Studio workshop, which he operates from his studio in Chino, California, and where he teaches art to children and adults. These experiences inform Wu’s artworks—particularly his drawings, paintings, and artist’s books—and they occupy a fluid intersection between his playful investigations of conceptual art, the painter-portraitist’s fond observation of those around him, and a form of institutional critique. The critique operating in Wu’s practice moves away from the model that has been dominant for decades—of attempting to expose forces that determine how artworks are produced, circulated, and consumed—and toward a version that incorporates homage and generosity.

I asked Wu about his art and teaching practices and his experience as a Chinese immigrant working within a Western framework of contemporary art. Wu’s work exists in tandem with the recent rise of figurative painting produced by artists of color. I am curious about what it means to be a person of color who produces figurative works that translate his overlapping relationships with institutions in order to speculate what art and pedagogy can aspire to. One clear implication of Wu’s work is that the “NOT ART YET” category is as fluid as the overlapping conditions that he has learned to navigate.

PHIL CHANG I’ve seen your paintings and drawings in person on a number of occasions in both exhibitions and in your studio, and you bring a high level of skill to your renderings of scenes that you photographed with your phone. There is a clear sense of mastery in how you reproduce your experiences. At the same time, your works possess a sense of naïveté and sincerity that can be disarming. Can you talk more about this relationship between mastery and innocence?

JOHN ZIQIANG WU People think about mastery as the opposite of the experimental and innovative qualities associated with contemporary art. I started out in art by learning Chinese ink painting when I was ten years old. The method was copying reproductions of paintings by Chinese “masters.” At the time, it didn’t occur to me to ask how big the original was and what was the quality of the reproduction. Or even, why do I need to copy the same painting over and over again? I began to work on watercolor painting probably in 2009, during my dad’s illness. Because of this family situation, I had to drop out of art school and take care of him. The watercolor drawings became a way to document the everyday and to calm myself during this period. In the institutional art context, it was clear to me that these drawings were not “high art,” they were just illustration drawings. But at least I was working on something that related to art making, and I gave them great value, because I poured my full heart into the process. Later, I kept working in that way alongside my “institutional art” that allowed for more thoughtful, clever, experimental, and conceptual ways of learning. From 2017 to 2018, I published many of my drawings in books, including The Lamps’ Story (2018), The People and The Place (2017), and Dad’s Hands Are Smaller (2018).

CHANG I find the sincerity in your work compelling, given our larger cultural ethos in the United States of irony, cynicism, and self-absorption. One place this sincerity appears is in your use of the English language. Your drawings, paintings, and artist’s books incorporate English in a loose way that would not be as acceptable in some other contexts. Can you explain how visually illustrating English words in your artworks functions for you?

WU I am not a native English speaker. I moved to the United States in 2005, when I was 25. I am still not good at English. But somehow, I have written things and taken notes in English. And I use English words a lot in my art, chart drawings, artist’s books, paintings with words, and storytelling. Am I thinking in English? Maybe yes, but how can I be sure? I feel my mind associates things with English words quicker. I realize that I use a lot of short phrases and incomplete sentences in my books. It isn’t that I couldn’t push myself to write a long, complex sentence with a subject, a verb, and a complete idea. I think it has more to do with my intuition about visual communication. I love to minimize all the unnecessary information in both making images and writing.

My exhibition from 2017, Learning Art and Art Learning Society, was an important moment that informed my growth as an artist and educator. It comprised a series of paintings, drawings, and photographs. There were also other components, including texts, poems, narration, a public drawing station, exercise sheets, and drawings and paintings by my students, including both children and adults. I inserted stories of learning and interpreting art into this show, such as, What are my parents’ and my students’ views of art and how do they parallel and overlap with my own views of art? There were moments of thinking, about my students, you will never understand what is art and how to make a good artwork, and there were moments when I saw how learning and making art has impacted their lives.

Almost all of my artist’s books are story telling. They are like children’s picture books, illustrated with watercolors. But you need to have an adult’s experience and imagination to fully understand them. One of the things I think about is, Where do art experiences come from? We go to museums to see art, and institutions create an official art experience. But there are also art experiences in everyday life, and they are often hiding in the unnoticeable moments. How to see it and give it enough attention, that is my creative spring. Like the The Lamps’ Story book, which poetically demonstrates an art experience rooted in everyday observations and asking questions.

CHANG Your drawings and paintings reflect your experiences, particularly your involvement with institutions such as the Hammer Museum, CSU Bakersfield, ArtCenter College of Design, and the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts). How do these experiences directly inform your works?

WU I feel every day is an opportunity to engage the world around me, if I can focus my mind and keep things simple. I see interacting with different places as an opportunity to personalize institutions and learn about the world that is normally outside of my reach and outside of the comfort zone of my studio and teaching practice. I feel the uncomfortable moments of being in new places and interacting with different people help me to see situations. The projects seem site-specific, if I look back. But I think people can find ways to engage with the work without knowing the specific places.

The People and The Place is a storybook set at CalArts, where I studied art. I didn’t plan to make a project out of small moments from everyday life. But in that book, I document making the query, “Hey Siri, what is surrealism?” during a studio visit with John Mandel. Now I know that is how I work, and I recognize situations that may trigger my imagination, such as an odd green lamp in a room that I observed for a couple of years [ The Lamps’ Story]. The banal is meaningful, and it has the potential to become everything.

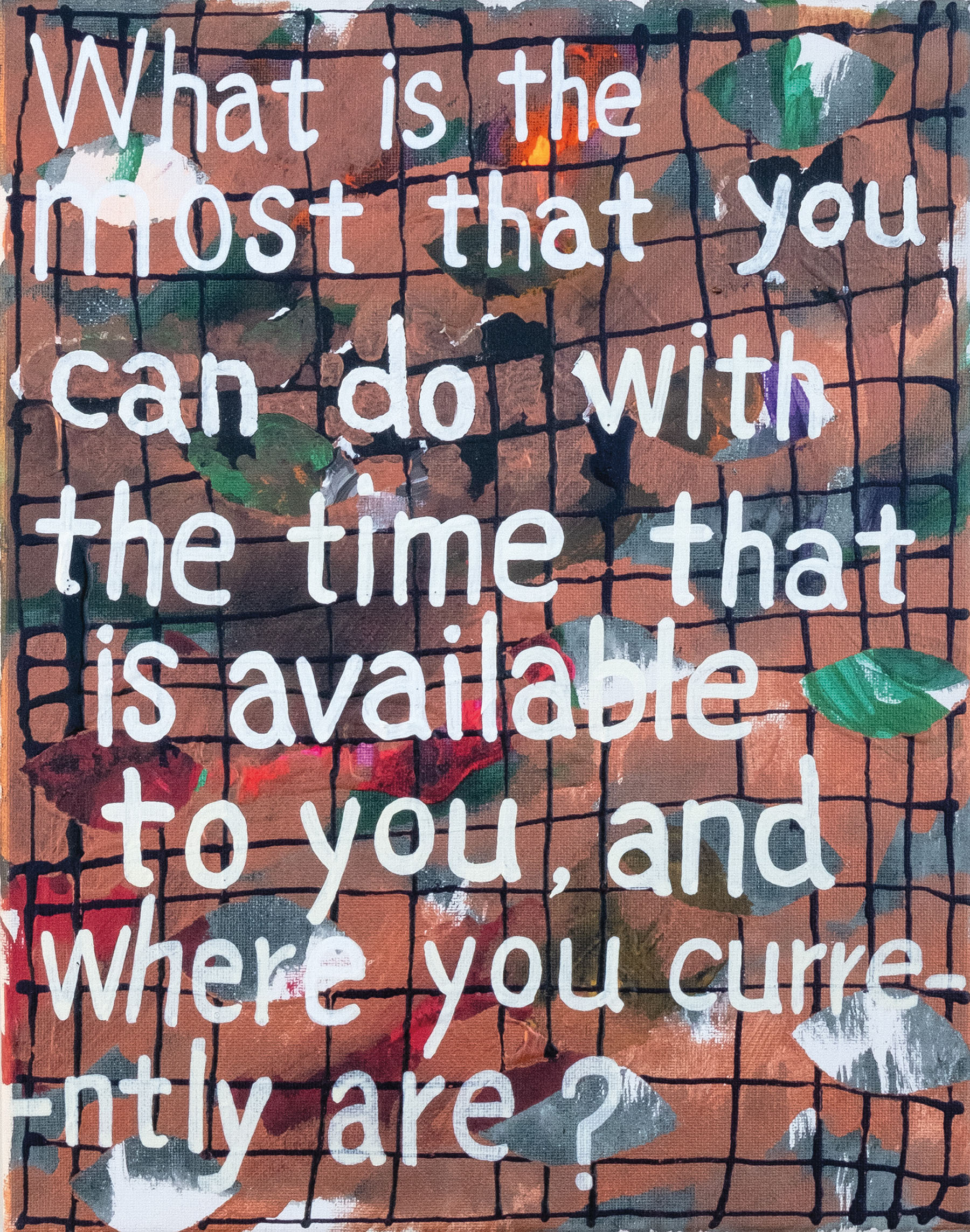

John Ziqiang Wu, Words from Phil, 2021, acrylic and oil paint on canvas, 14 × 11 in. Courtesy of the artist.

Phil Chang is an artist living in Los Angeles. He teaches in the Department of Art and Art History at California State University, Bakersfield.