Chaos in the Palace (2015), a work by Waswo X. Waswo, is the latest from a series of contemporary miniatures created in long-standing collaboration with the miniaturist R. Vijay at Waswo’s Rajasthan studio. Waswo describes the work as such: “Beneath what initially strikes as lighthearted satire, even a comedy of errors, Chaos in the Palace contains a subtext of a world caught between high-mindedness and intellectual dishonesty; self-indulgent decadence and anti-intellectual destruction.”1 Before the viewer’s eyes unfolds a panorama comprised of eighteen miniature paintings arrayed in two rows of nine. Each depicts an identical architectural interior, though the tremendous jostle of color combinations varies from frame to frame. Against these variations, many scenes are staged, and well-known artworks—both Indian and Western—play various roles in the patchwork of narratives that the viewer pieces together. Pallid bone frames offset intense, garish, and clashing color schemes that are atypical of the palette of hues used in traditional miniature painting, signaling that this suite of works intends to deploy contemporary devices and images to make a bold statement about the current world in which we live.

How does this suite of works take on the challenge of engaging us in this complex set of issues? What themes emerge to provoke us to question the nature of the contemporary relationship between the artistic and the political, the art market and the polis, and cultural production as a form of speech? What of attempts to gain hegemonic power through the censorship, repression, and outright violence against certain forms of expression deemed offensive, unacceptable, “hurtful to the sentiments” of someone in a position of power, or even seditious and “anti-national”?

A little background to the predicaments faced by contemporary artists in today’s India helps contextualize the weight of such accusations as being “anti-national.” Under the right-wing Hindutva regime of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the term “anti-national” has become a popular slur against anyone out of line with the regime’s brand of Brahminical Hindu nationalism. “Anti-national” is widely used to assert that dissent of any form is un-patriotic and an attack on the nation itself. Hence the term is used to forcefully silence oppositional discourse with the threat of sedition charges and beatings by self-designated “patriotic” defenders of the idea of India as a Hindu nation. The governing Brahminical hierarchy denies the full personhood and citizenship claims of Others, ranging from women to homosexuals, from Dalits (once referred to with the pejorative term “Untouchables”) to Muslims, Christians, and Sikhs, as well as so-called “Sickular” (i.e. secular or atheist) and “Libtards” (i.e. liberals and progressives), as defined by the regime and, in the case of the latter two epithets, by its supporters and trolls. In spite of myriad relevant differences, it is not hard to see a homologous ethos at work in the aggressive ideology of presidential hopeful Donald Trump and his henchmen and minions, who have a very particular notion of the kind of racial, ethnic and religious “cleansing” needed to “make America great again.” These patterns are not exclusive to India and the United States but rather bespeak a growing wave of ultra-right wing invidious and exclusionary hate politics on the rise across the world. So the critiques implicit in this suite of artworks speak to a problem that is not exclusive to the Indian context, even as the imagery and some particular terms are derived from it.

The epithet “anti-national” was mobilized to dire effect in India during state efforts to crush and silence the student movement across the country that arose following the January 2016 suicide of Rohith Vermula, a Dalit PhD student at University of Hyderabad. Vermula committed suicide after being hounded, beaten, deprived of his stipend, kicked out of the dormitory, and then suspended from the university on fabricated charges. Protests swept the country, and a similar situation emerged at Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), in February 2016, when the JNU Student Union Leader, Kanhaiya Kumar, was arrested on charges of “criminal conspiracy” and “sedition” based on allegations of “anti-national” speech. He was then brutally beaten by a brazen mob of right-wing Hindu lawyers inside Delhi’s Patiala House court, and journalists attempting to document the beatings were threatened. Student activist Umar Khalid and others have met similar threats and slander. Intellectuals around the world roundly condemn the use of charges such as “anti-national” and “sedition” to silence free speech and dissenting public opinion.

This is the context in which contemporary Indian artists make their work, and Waswo’s Chaos in the Palace speaks to that context. It is a perilous minefield and the stakes grow commensurately with the dangers they face for opposing the Hindutva line. This precarious situation has a long history dotted with periodic explosions of violence against, as well as censorship of, artists; both have been quite pronounced since the early 1990s.

Waswo’s position in this history is complex. As an American, born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in 1953, Waswo has lived in Rajasthan since 2001. He shed his former identity and replaced it with an X, which is bookended by repetitions of his surname. Art historian Kavita Singh proposes that, in making India his new home, the artist also remade himself, becoming both “Waswo ‘ex-Waswo’” (the Waswo who is no longer Waswo, or the artist formerly known as Waswo) and also Waswo redoubled—perhaps more fully becoming his immanent self.2

Waswo X. Waswo and R. Vijay, Chaos in the Palace, 2015. Suite of 18 miniature paintings, gouache and gold on wasli. Courtesy of the artists.

Initially, with the publication of his first book, India Poems: The Photographs, Waswo was met by kneejerk criticisms equating a White Man making art in India with the evils of Orientalism and questioning his right to participate in the Indian contemporary art world.3 Using the usual charges of “appropriation,” critics challenged his right to use Indian visual languages. It is telling that their ire was directed primarily at Waswo’s photographs that depicted the working class poor and the poverty of rural India, which some Indians apparently deemed unsightly embarrassments. Yet lauded Indian photographers such as Gauri Gill and Ravi Agarwal have done extensive work with poor rural and laboring communities without facing similar criticisms. It is hard to deny that what was at stake in these criticisms was Waswo’s whiteness and foreignness as purported disqualifiers of the right to “speak” within an Indian visual vernacular. Some claimed his early photographs were attempts to smear India’s good image by using pictures of the poor and so-called “backward” to deliberately elide the splendor of India’s development, growing wealth, and urbanism.4 Yet, it was precisely in these places where Waswo found so much dignity, beauty, and reason to love his adopted home.

Nevertheless, these criticisms led Waswo to great soul searching, sending him on the path of a deeply self-critical, self-reflexive art practice. He pushed himself to imagine a process of making art that confronts and questions the position of the White Man in contemporary India, without relinquishing his desire to belong and be a genuine member of the community. With self-mocking satire (sometimes as hyperbolic parody of what he perceives his critics project onto him) and tongue-in-cheek humor that hints he is indicting us all along with himself, Waswo explores questions of post-colonialism, Orientalism, White privilege, and the place of Others within adopted communities, whilst refusing to evacuate the position he has worked to create for himself in both the art world and his local community in Rajasthan. Many of his works, photos and miniatures alike, feature the Fedora Man, who is Waswo’s alter ego; at times he takes the guise of “Evil Orientalist,” bumbling tourist, and ordinary Everyman traveling though incredible India.

The foundation of Waswo’s sustained engagement with the local community in his adopted home is a commitment to the sort of fair labor practices and ethical collaboration with local artists (who were completely outside of the contemporary art world and unknown beyond the local scene) that goes far beyond most artist-fabricator relationships in the contemporary art world. In spite of the fact that he alone conceptualizes and designs the works, he still pays his collaborators for their work outright, gives them additional bonuses from sales, and flies them at his own expense to openings across India and the world. It is noteworthy that he also insists on naming them explicitly as collaborative partners and even having them co-sign the works. This kind of labor practice is virtually unheard of in India and, indeed, in most parts of the global contemporary art world, where craftspeople and fabricators labor in poorly paid obscurity. In contrast, Waswo treats his collaborators with a professional dignity that has earned him respect and acceptance within the Indian contemporary art world.

Flying in the face of preconceived notions of the White Man as necessarily and inevitably Orientalist, which are prevalent in the Indian media, Waswo’s sensitive practices and ethos of fair and credited collaborations have led many Indian scholars and art historians, such as Kavita Singh, to argue that Waswo should be acknowledged as an Indian contemporary artist in his own right, due to the intimate and conscientious nature of his long-term investment in and deep engagement with both India and its aesthetic traditions.5

Today, Waswo is well known as a conceptual and installation artist, as the conceptual force in his collaborations with traditional miniaturist R. Vijay and others, and as an accomplished photographer, working closely for over a decade with traditional photograph hand-tinter Rajesh Soni.6 He is a devoted print collector who has championed Indian printmaking for years, sharing his collection with museum-goers across India and abroad. Even still, the specter of nationalist politics continues to haunt him, as it does many other artists in India.

While Chaos in the Palace is not heavy handed, the work raises the question of what happens when art and politics intersect, particularly with the latter’s attempt to stifle free expression again and again throughout. To explore these questions, some grounding in the project’s specific imagery is useful.

The visual framing device repeated in all 18 frames of the Chaos in the Palace suite is derived from the depiction of a palace interior attributed to Shaykh Zada and painted to accompany a fifteenth-century manuscript illuminating the Persian poet Sa’di’s Bustan.7 One of the great literary works of the thirteenth century, Sa’di’s Bustan (The Orchard, 1257), chronicles the struggles of Muslim peoples through stories that exemplify their virtues and critique their failings.8 A man of great literary talent but limited economic means, Sa’di could not offer the customary opulent gifts, so instead he composed the Bustan—an epic poem that he described as a “Palace of Wealth,” with “ten doors of instruction.”9 He offered this “palace” to the world as his gift: “I regretted that I should go from the garden of the world empty-handed to my friends, and reflected: ‘Travelers bring sugar-candy [dates] from Egypt as a present to their friends. Although I have no candy, yet have I words that are sweeter. The sugar that I bring is not that which is eaten, but what knowers of truth take away with respect…like dates encrusted with sugar—when opened, a stone [pit] is revealed inside.’”10

The “stone” of the fruit is the kernel of truth that the stories are meant to reveal; hence the title “The Orchard” describes the treasure contained behind the doors of his palace of instructional words. The works in Chaos in the Palace are akin to such doors; beneath the bright, “sweet exteriors,” they offer hard, sharp stones of insight about our current condition.

Many of the stories in the Bustan emphasize a cosmology of predestination and the uselessness of railing against Fate. One passage recounts the loss of fighting spirit by an old warrior who suffers defeat at the hands of the Mongols: “‘O tiger-seizer!’ I exclaimed, ‘what has made thee decrepit like an old fox?’” The newfound wisdom of the man is expressed in his realizations that Fortune is not in his favor, and “only a fool strives with Fate.”11 Elsewhere, Sa’di tells a story to illustrate that even theft is preferable to slander and backbiting: “Thieves,” he explained, “live by virtue of their strength and daring. The slanderer sins and reaps nothing.”12 We find echoes of these lessons, albeit transformed by the indexical context and historical specificity of the times, in Chaos in the Palace.

Chaos in the Palace shows us the politics of art making, both within India and internationally, but while Sa’di’s offerings are allegorical stories of moral guidance in the format of an epic poem, Waswo’s are an intentionally chaotic juxtaposition of insights and critiques about the intersection of art and politics on a number of intertwined yet distinct levels. The work hints at flows of hegemonic art-world value systems from “Occident” to “Orient” that privilege particular kinds of art practices and encourage the production of easily recognizable and digestible artworks. This system rewards art production that manages to finesse a politics of appropriation. Such appropriation takes place either in the realm of visual language (new wine, old bottles) or in easily assimilable themes and subject matter rife with exoticized, essentialized references to “Indianness” (old wine, new bottles). This same international art market is inept at recognizing work that does not fit neatly into either of these two categories. Waswo pokes fun at this, throwing the colonial “palace” of the art market into chaos with visual and referential moves that span the gamut from parodic to paradoxical.

In keeping with his characteristically self-reflexive, self-critical art practice, Waswo never offers faux “impartial” critiques from on high, nor does he pretend he can take a fully critical distance from his own position as an artist of Western origin who has struggled to make a genuine and legitimate space for his art practice within his adopted home of India. Indeed, throughout the suite, no one is spared, and everyone, including himself, is implicated at the nexus where national politics, cultural politics, art market politics, visual and poetic politics, and personal-as-political politics collide, conjoin, and confound attempts to be disentangled into neat, linear, separate threads. As such, Chaos in the Palace varies in important ways from Sa’di’s guide to the moral and ethical behavior of Muslims in the world. While the “ten doors of instruction” in Sa’di’s palace open into neat “orchards” of teachings about proper conduct in various realms—ranging from those of justice, benevolence, love, humility, resignation, contentment, education, and gratitude to repentance and prayer—Waswo’s eighteen panels do not offer such unambiguous teachings. Instead of opening up into “orchards” of orthodox learning, they contain their lessons within the confines of the palace itself, forcing us to draw comparisons and connections between the scenes unfolding simultaneously across the tableaux he creates.

There is no proper sequence or prescribed pairing between panels arrayed left to right and top to bottom. It is entirely up to the viewer to find herself and the world in which she is located and participates within across, betwixt, and between the scenes. Waswo forces us to become active makers of the critical meaning within the work, to make assessments and judgments, to take stances and stands, and thus to explicitly implicate ourselves in the chaos in the process. If you read the suite of images from left to right and top to bottom, narratives about the politics of art, the struggles about what art should be and for whom, and whether art should be controlled or free expression allowed in the public sphere emerge, raising questions that the viewer is left to ponder.

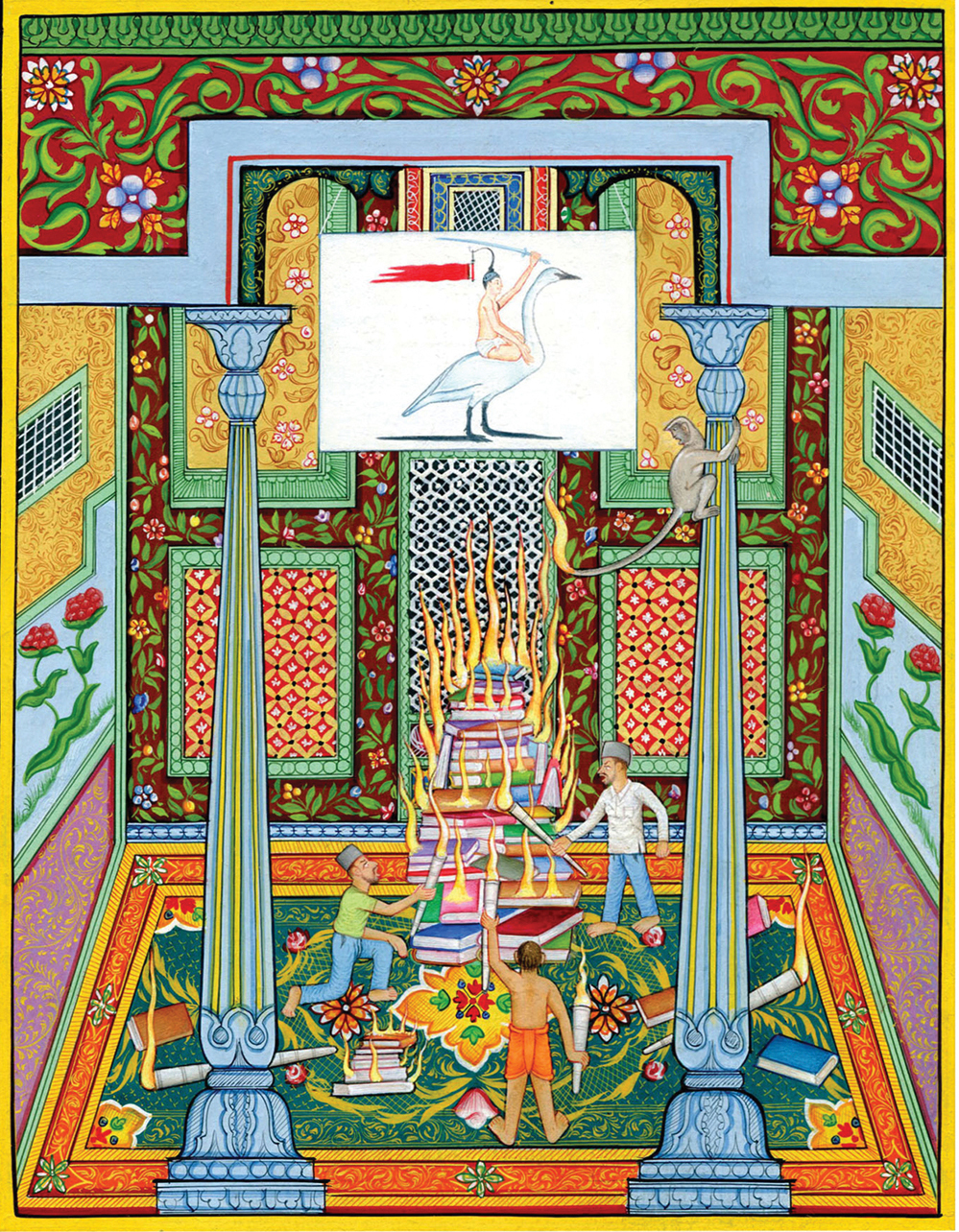

In the first image, Waswo borrows the figure of a man mounted on a swan with sword raised from Surendran Nair’s Cuckoonebulopolis (2004) series. The “cuckoo” polis, where reason no longer seems to hold sway and the sword is mightier than the pen (or pencil or paintbrush), could easily be any number of contemporary places in the world in which we attempt, as creative people, as intellectuals—as artists and thinkers and citizens—to make our art and make our lives. It is a place where things no longer make rational sense, and the power of the once great forces of secular humanism has been dwarfed by fundamentalists, extremists, and other people for whom knowledge, education, literacy, logic, reason, and rational argumentation have been overshadowed (or overwhelmed) by the slings and arrows (tridents and machetes, guns and knives and lathis) of those for whom freedom of thought and expression are evils to be contained, suppressed, and crushed out of existence. This could be any place on this earth today where freedom is under grave threat by organized forces of intolerance, most often mobilized in the name of religion and/or nationalism. Hindus, Muslims, and Christians all appear in these panels and, while none is singled out, neither is any let off the hook.

In the panel below, we see people toppling a bust of Voltaire in ways that mimic the decimation of statues in Palmyra and the intentional destruction by the Taliban of the Buddhas of Bamiyan in Afghanistan. In the background of these acts of cultural violence appears a reference to Mahatma Gandhi’s once powerful and effective use of non-violent resistance. The iconic Nandalal Bose linocut print in black and white, entitled Mahatma Gandhi (Bapuji) on the Dandi March, 1930, depicts Gandhiji with his walking staff commemorating the Independence movement and the pivotal 1930 Salt March, which protested the Salt Tax of the British on India; after the march, he was arrested. Tellingly, in Waswo’s composition the picture hangs tilted and ignored in the background.

In this panel and in many throughout the suite, monkeys take up various stances alongside men, blurring the boundaries between the human and the animal. For Waswo, “we are all monkeys,” sometimes as trouble makers, sometimes as helpless “mute spectators,” “victims,” or “refugees,” and they should “remind us of our origins.” We are, in spite of all our sophistication and learning, still animals. For Waswo, perhaps it is primarily our learning—our literacy and capacity for abstraction and art—that differentiates us from our primate ancestors. Non-human animals who lack our vast historical accumulations of knowledge and culture do not engage in the kinds of vicious, calculated cruelty and destruction that our species does with alarming regularity.

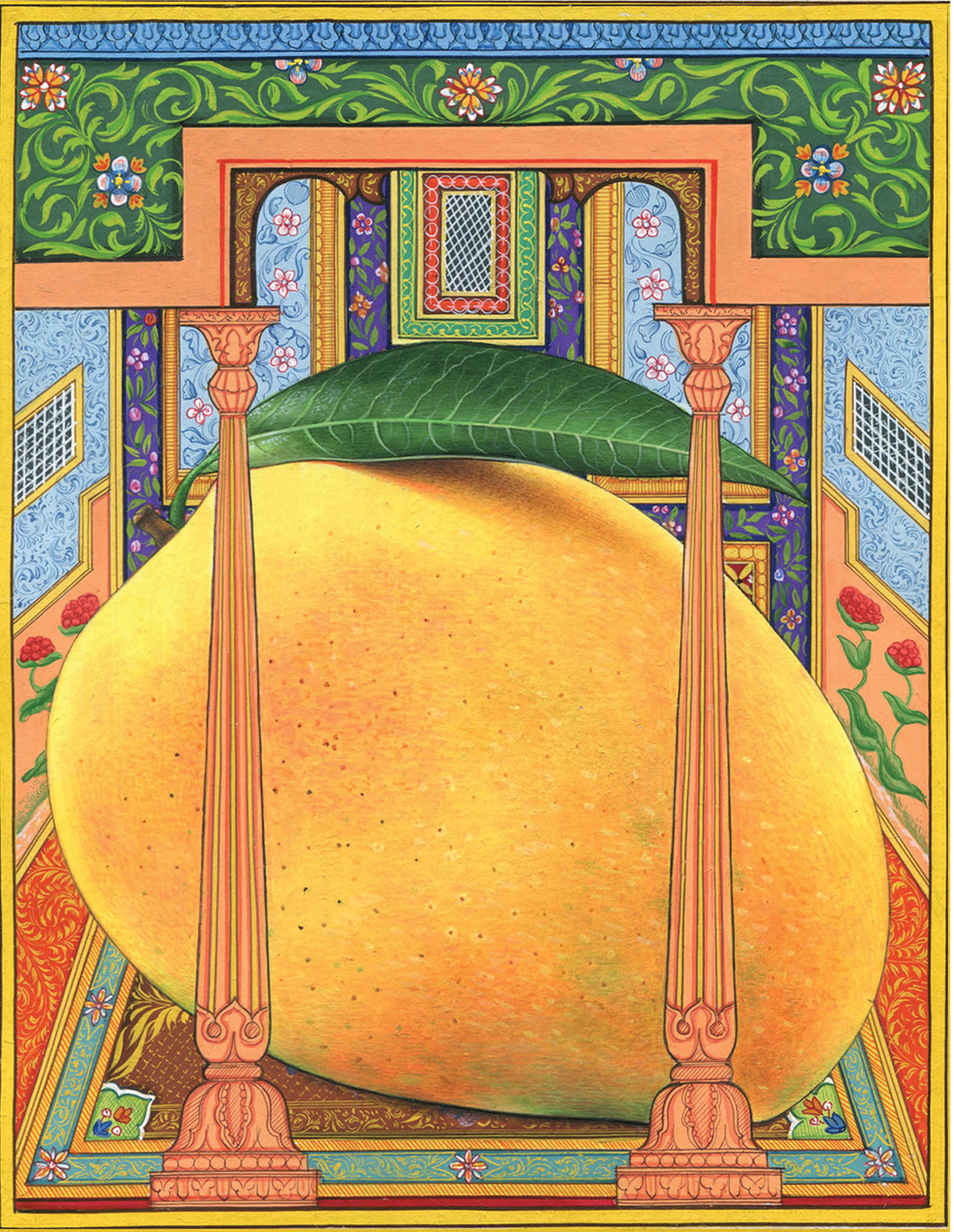

It is important to note that, for Waswo, the chaos explored in the suite of works does not arise from a simple secular vs. non-secular binary. He writes: “There are other threats to the ‘palace’ of contemporary society as well, and perhaps this palace ought to be under threat.” The same is implied for the international art market’s system of valuation. Indeed, we see this clearly in the next set of panels, which depict the copying of René Magritte’s famous The Listening Room (1952) in juxtaposition with a giant mango that takes up the entire palace in the panel above. This juxtaposition begs the question of what is lost. Having spent over a decade working with practitioners of traditional Indian art forms, such as miniaturist R. Vijay, Waswo has an intimate sense of this threat. What is lost includes “possibilities of an art based on and evolved from Indian experience, technique and history,” he explains, because of the overemphasis in India on “copying” art from the West, as encouraged by the international art market.

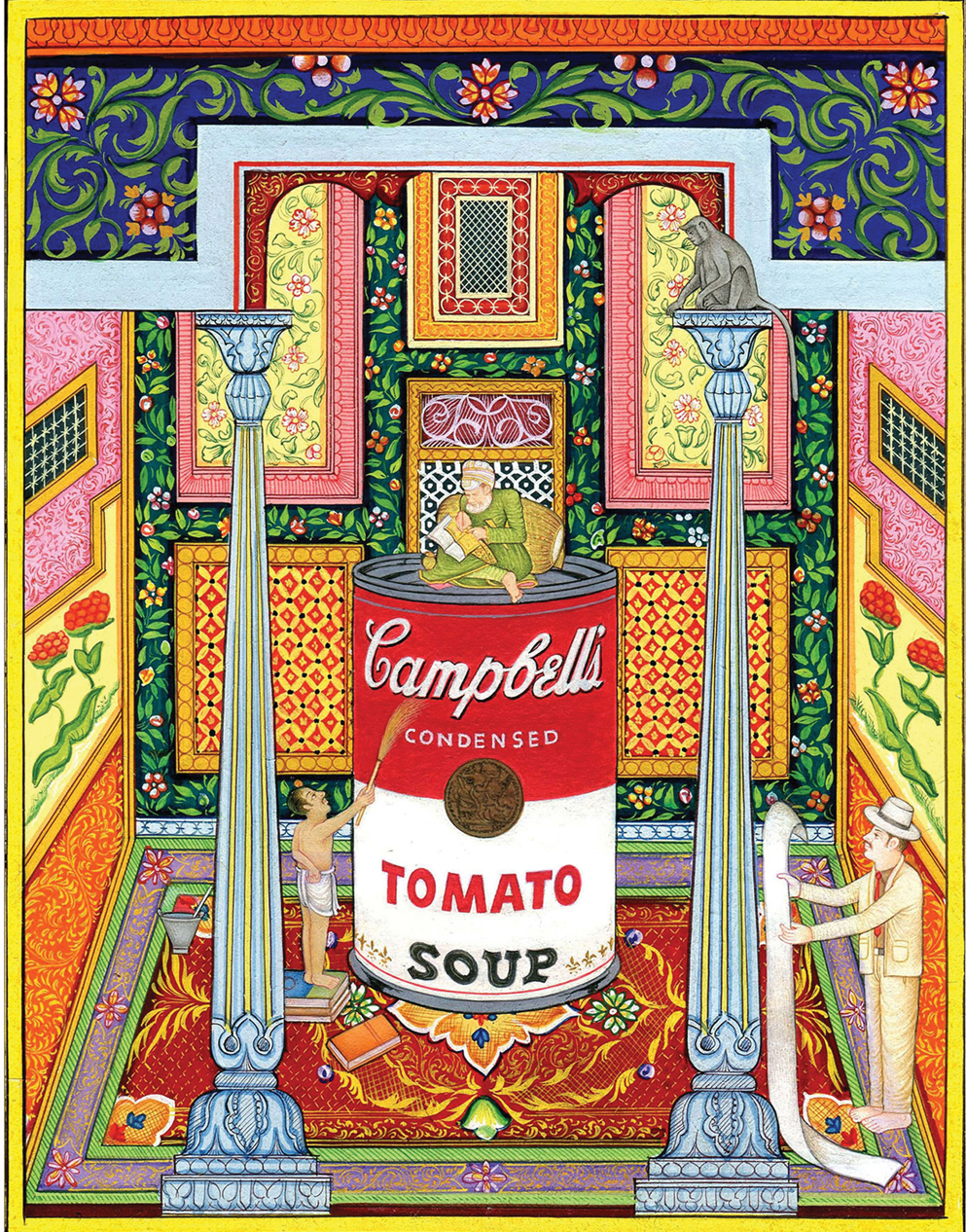

Thus, the threats emanating from the politics of capitalism and its “mass marketed consumption” also throw the palace into chaos, albeit in ways different from what the competing fundamentalisms and extremists do. In the next panel, we know neither what the scribe perched atop a representation of Andy Warhol’s iconic 1962 Campbell’s Soup Can is writing nor what the Fedora Man is writing. And perhaps the content is not what matters but rather the significance of the acts of reading and writing, and what literacy means for the possibilities of having civil societies. What happens when the forces of the market invade the realms of scholarship and intellectual life? Is this not, in its own way, as much a threat to free, meaningful expression as fundamentalism? Meanwhile, a boy dusts the soup can with a vacant expression—neither the words nor the art mean much of anything to him. Without literacy and learning, whole worlds of meaning are simply closed off to us, and under such circumstances, it is little wonder that we do not value them.

Appropriation and imitation reappear in the next panel, with a scene that replicates a famous Norman Rockwell painting, entitled The Connoisseur (1961), which itself features a work by Jackson Pollock and pokes fun at the elitist art world. Note that this same “Pollock” painting reappears in another panel, in the room where forgeries of Magritte’s apples are being made. Fedora Man’s hat is off (as in the Rockwell piece), but his shoes are on, showing a tension between typically Eastern and Western modes of showing respect indoors, and the object of respect is of questionable authenticity.

In another panel, Waswo’s use of contemporary artist Alwar Balasubramaniam’s famous sculpture of arms, which are here used as a dividing line in the adjacent piece and also as a laundry line, evokes boundaries between high and low culture and art. Just as the boy mindlessly dusting Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Can points to the decisive role of cultural literacy in the formation of our value systems and the ways that our mutual ignorance of each other’s ways of life and cultural forms enable us to also devalue each other and Others more generally, Waswo draws attention to the way that art can fail to engage with everyday life. Here something is lost as the “manual is subverted into [a] preciousness” that is illegible to the laborers working in the same scene. Balasubramaniam’s exquisite white sculptural arms, which are typically shown in a pristine, white-cube art space, here are used to hang out the wash, in a scene where actual manual labor is going on all around. This is neither to simply condemn the art world for its elitism nor to denigrate the laborers for their lack of cultivation, but rather to show the disconnect that happens across these spheres and to question what an art that is unintelligible to ordinary people actually means, and how much is lost on people who are excluded from the creative discourses of the “high arts.”

Complicity of all parties in creating the chaotic mess we’re in is another critical theme that permeates the suite. Waswo does not exempt himself. The complicity of the Fedora Man in what Waswo describes as “the entire scenario of image-making, ego, marketing, and selfishness” is clearly evoked in another panel. Acting as a court photographer, with servants prostrating themselves below on the carpet, the Fedora Man both appropriates imagery from the local scene to serve his own interests while also serving the ego and power of the king being photographically memorialized. Meanwhile, the monkey observes from on high, mimicking the king. What are we doing here? How is each one of us implicated?

Themes of self-indulgence and mental masturbation, metaphorical fiddling while Rome burns, appear with the invocation of another iconic Balasubramaniam sculpture. Waswo places the seated white Balasubramaniam figure out of context and into what he describes as an “ornate jali” (hand-carved wooden screen) in the palace. The figure appears to be slouched over in the onanistic act of self-pleasuring, while the writer in the foreground indulges in a similar kind of masturbatory action, producing words to please himself without reaching any actual audience. Here the rope and arms from the previous panel attempt to delimit a boundary between high and low, elitist “art” and popular culture, the spheres of cultured elites and the plebian Everyman. Yet against this backdrop, the natural world—as invoked by Waswo’s recurring monkeys and peacock—carries on without a care for what the men in the scene are doing.

This self-indulgence continues in another panel, as the Fedora Man smokes a hookah pipe in a pose that references Waswo’s own well-known miniature work, Dream of the Mirrors (2012). He appears lost in his own naval gazing, on his own trip, much like so many foreigners who come to India seeking spiritual enlightenment, bringing their exoticizing, essentializing assumptions with them and only seeing India through their distorted lenses. While the man remains immersed in his self-contemplation, the balloons in the panel drift aimlessly away, signaling that perhaps the “party is over” without us even realizing it yet.

The party balloons are echoed in Waswo’s appropriation of Jeff Koons’s Balloon Dog sculpture (1994–2000), which appears in the preceding panel. This particularly expensive and (in)famous artwork has become an icon of the utterly frivolous consumptive excess of the blue chip Western art market. The more common, less glamorous balloons in its midst at least can float or fly, while the Koons balloon dog of mirror-polished stainless steel is grounded, stuck, and inanimate. It is contained in a zoo-like environment with the monkey, a domesticated commodity animal alongside a wild animal that is often imprisoned for human entertainment and exploitation. But while the art is easily containable in the “zoo,” the beautiful tree on which the monkeys and birds congregate cannot be contained, and it grows beyond the frame. The tree’s roots are anchored in the panel below, where Warhol’s portrait of Marilyn Monroe hangs, an icon of Western pop sexuality, fame, glamour, celebrity, and beauty—superficial things that we often seem to value more than knowledge, learning, literacy, and creativity. In this context, however, Marilyn hangs off-kilter, and monkeys play with it like a toy, suggesting that in the end it is nature that has more vitality than culture.

Human vanity, self-obsession, and nature are addressed frequently in the suite, symbolized by mirrors and peacocks, which are emblematic of the crass, callous manner in which we humans appropriate nature’s splendor to adorn ourselves. But nature is not passive, and Waswo’s paintings imply that, as much as we would like to fantasize, we are not its keepers. Watch out for the snake, which, unlike the decapitated tiger, is still lurking and very much alive. The theme of devaluing nature or only being able to see its worth within a calculus of our own instrumentality repeats pointedly in a nearby panel that again features peacock feathers. But we can also see both literal and metaphorical consequences in the next panel, where the Fedora Man stands with his flimsy, useless umbrella, impotent against nature as rain clouds lay siege to the palace, occupying it from within. Water cascades across the floor, threatening to flood the building and hinting at the forces of nature expressed through freak weather and storms. The broader implications are that the excesses of capitalism, industrialized agriculture, and use of fossil fuel are forcing us to start reaping the seeds we have sown.

If we have jointly, unwittingly, created a world in which forces of intolerance, anti-intellectualism, inequality, deprivation, ecological degradation, and natural disaster are now shaping the spheres in which we live, work, and attempt to create culture, what role can art play in addressing this new world we have brought into being? What kinds of art appear in these tableaux in the palace, and what is the status of art in relation to political and cultural life—elite cultural masturbatory self-indulgence or actual social significance?

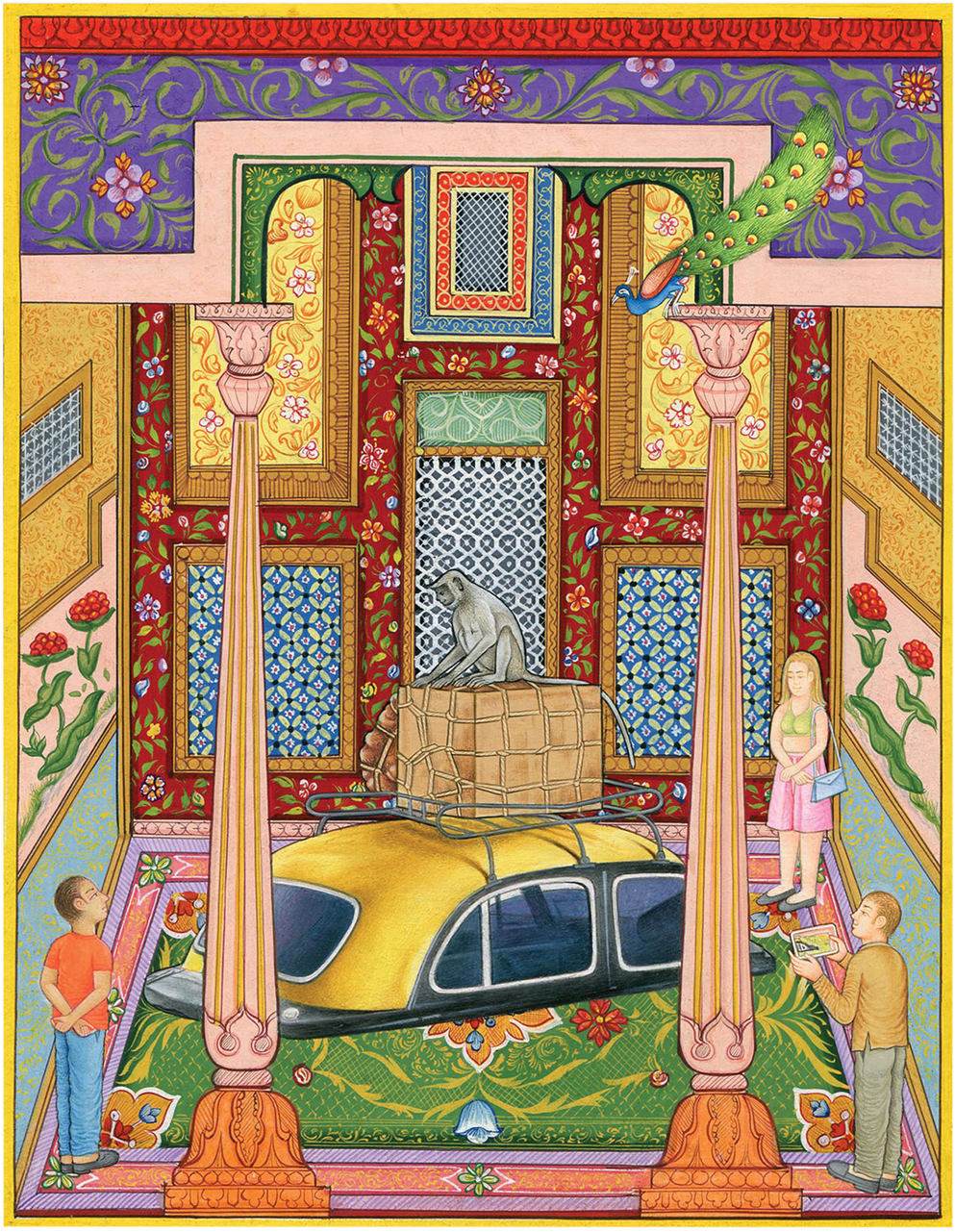

In the following panel, we see what might be Waswo’s approximation of a modest rejoinder to this massive, entangled mess of questions, as he contemplates “What now?” In this room of the palace, Subodh Gupta’s kali-peeli black-and-yellow taxi sculpture Everything Is Inside (2004) is the focus of attention. Here Indian art has arrived on the international scene in a form that is neither exotically essentialized nor overtly pandering to a pop culture of faux luxury endemic to the Western art market; rather it trades on an everyday object that is part of ordinary urban Indian life, capturing the attention of viewers foreign and Indian alike. A socioeconomically mixed crowd comprised of a scantily clad white woman (perhaps a tourist or a collector) and both brown and white men are all observing Gupta’s partially submerged taxi. The monkey appears to be untying the ropes that lash the luggage to the roof carrier, and the peacock looks ready to join in. This work is in noticeable contrast to some of the other art-market-star works that appear in this suite, including Warhol’s Marilyn and Koons’s Balloon Dog—both icons of pop glamour and consumptive excess. Of Gupta’s taxi sculpture Waswo has said, “It is real and people relate to it.”

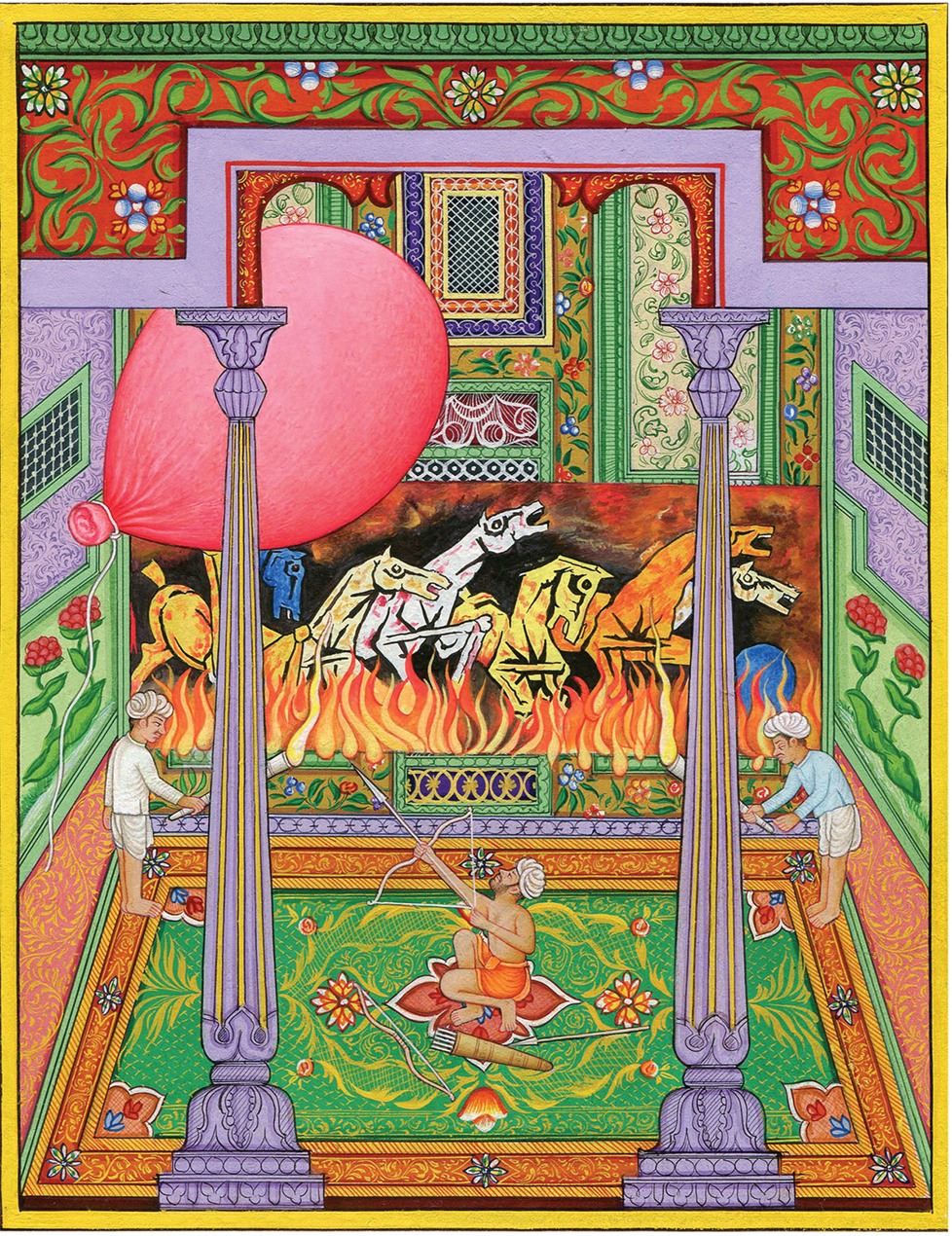

But just as Indian art is beginning to find its own place in the international art world, it is coming under increasing attacks at home. In a later panel, a balloon reappears; this time it is overinflated and about to burst. Is it the art market in general that has grown too big for its proverbial britches and yet simultaneously too empty—a literal bubble waiting to burst? Or is this brief moment of Indian art itself in danger, not only from the international forces discussed earlier, but also from forces gathering momentum domestically?

The arrow pointed at the balloon is also the symbol of the far-right Hindutva organization, the Shiv Sena, which has been instrumental in many attacks on cultural expression and on cultural Others in Mumbai and beyond. The work of modernist painter M. F. Husain depicted in this panel warns of the destruction that this other kind of gathering storm cloud—religious intolerance and fundamentalist extremism—can visit upon cultural expression. Husain’s importance as a leading figure in the development of Indian modern art is well known, and the threat to all artists and culture producers who run afoul of sectarian, communalist forces is well documented in his case. While Husain believed his secularist visual interpretations of the Hindu iconography to be part of the shared inheritance of Indians of all backgrounds, his works and person were attacked by the far right with such virulent ferocity and unbridled hatred that Husain was forced into exile. He lived out his final years unable to return to his homeland due to threats of grave bodily violence, against which the state offered little protection.

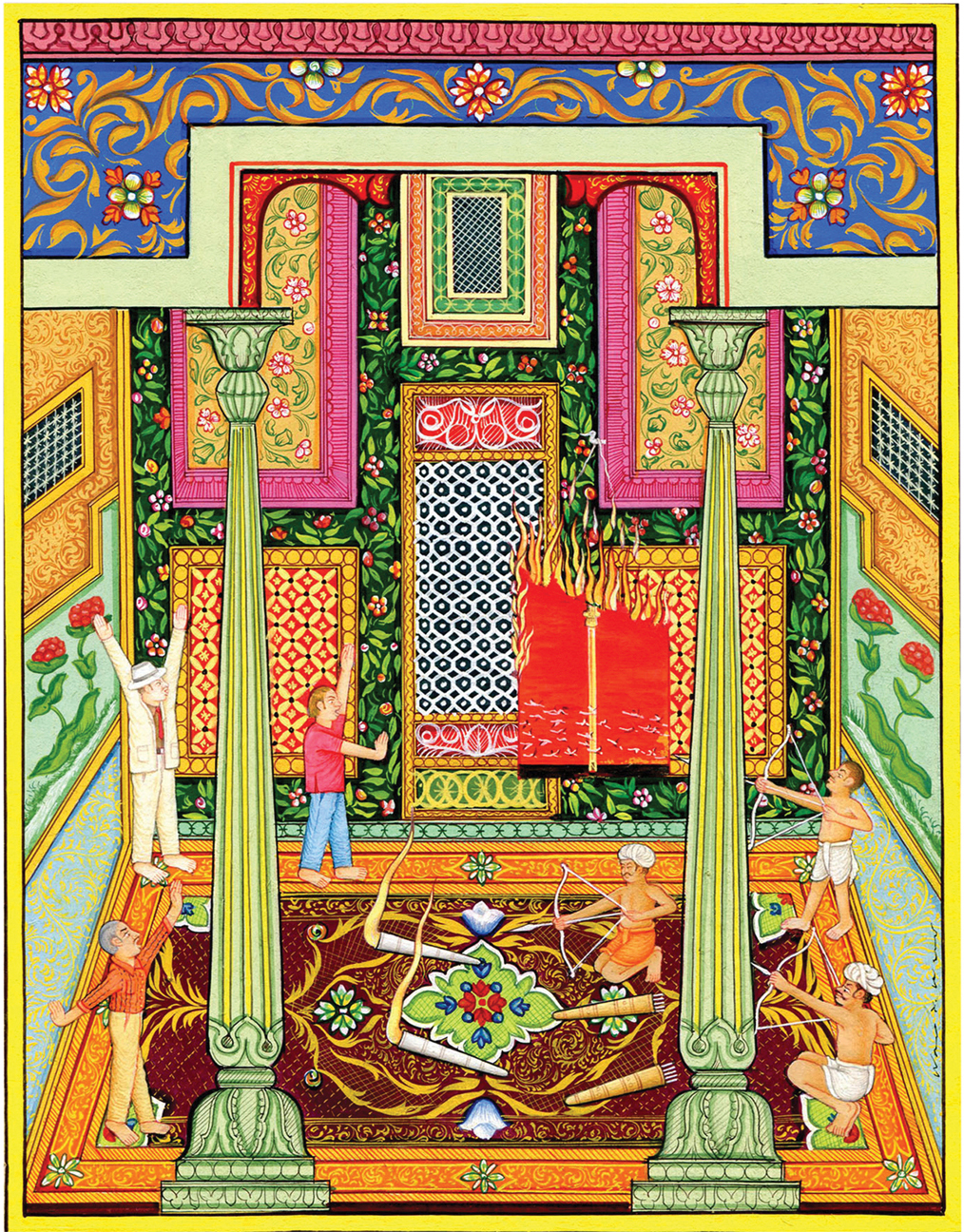

So what is to be done in the face of so many threats to free expression and intellectual and cultural production? The Fedora Man does not have any answers. He is overwhelmed, just as most of us are, and part of him seems to want to give up. All around him is violence, books and paintings are on fire, and people are armed and ready to kill each other. His hands are in the air in a universal gesture of helplessness and acquiescence. Shilpa Gupta’s 2007 series There Is No Explosive in This—in which a microphone sings, “hands in the air, hands in the air” again and again—comes to mind.

The painting on fire in this panel is An Actor Rehearsing the Interior Monologue of Icarus (2000), by Surendran Nair. Thus Waswo closes the brackets begun by his evocation of Nair’s work in the first panel of the suite. Nair’s An Actor Rehearsing depicts Icarus standing on the Lion Capital of Ashoka Pillar, a symbol of India. His painting was yet another well-known artwork that was attacked by far-right extremists, who forced its removal from a public exhibition in 2000. “Like this painting,” Waswo narrates, “Chaos forebodes an impending doom, a fall from grace, though the environs are couched in the pretense of grandiose dreams.”

In this fall we are all complicit. Waswo’s cultural collaborators and longtime local friends appear in the frame as well. The Fedora Man is joined in this final panel by a red-shirted Rajesh Soni, the artist who hand-tints Waswo’s photographs. The gray-haired man in the bottom left corner is R. Vijay, who has executed the painting of this very work. “We are complicit, and will meet our fate,” Waswo writes. “Secularism, the Enlightenment, Free Speech…all threatened from inside and without. The barbarians (I will call them that) are at the gates (on both sides of the suite) and they are only met by a painting of a silly man on a goose in this palace of Cuckoonebulopolis.” What are we doing to hold back the rising tide of hatred and intolerance, violence and oppression? And where have the monkey and peacock gone? They may be victims of human greed and stupidity, but this is not their fight, and they are not complicit the way we are.

In this rich and turbulent suite of works, Waswo raises painful questions. He asks us to consider both the importance—and also the relative impotence—of art, ideas, creativity, humanism, and secularism in the face of rising anti-intellectualism, right-wing fundamentalism, and violent fascist extremism. In short, this work not only is about India today but also darkly parallels the United States, Europe, and much of the rest of the world, where similar processes are unfolding around us in spite of our feeble interventions. In our world today, chaos has indeed been unleashed in the palace. For Sa’di, the palace was a cultural construct made of words, with “doors of instruction” opening out into orchards filled with fruits that were sweet but contained a hard stone in the center—a kernel of truth, as it were. In Waswo’s palace of aesthetic and political visions, there are no doors; we are trapped inside, with no discernible way out. The orchard isn’t out there beyond its doors, and the teachings offered are not the clear moral and ethical instruction that comprised the pith of Sa’di’s Bustan. In Waswo’s palace, as in our contemporary world, chaos and violence have overtaken righteous conduct and ethical living, yet ironically, the book burners, the painting torchers, the art hawkers and gawkers all also believe in their own morally unambiguous slanted truths.

While the suite explores the politics of art making and art consumption—by whom, for whom, for what purpose, and to what effect—it also examines the politics of imitation, appropriation, and hegemonic standards for evaluating what is desirable. These often-arbitrary standards frequently elide something more interesting, more locally colorful, with greater local significance and flavor (the mango instead of the apple, as it were) in the process. Indeed, these things can be a form of violence as well.

How do we face the violence being unleashed in these dark times, and what good is our art, what use are our ideas, our pacifism, our non-violence, our tolerance, and our secular humanism in the face of such brute mob violence and hubristic demagoguery? Because Chaos in the Palace is about brutally enforced censorship and the dangers of self-indulgent complacency, navel-gazing, partying, and fiddling while Rome burns, it challenges us to ask, out of this chaos, what? What is to be done? What can we—through our ideas and our art—do?

Unlike the unambiguous guidance for right conduct, morality, and justice offered in Sa’di’s “palace of wealth,” these questions are left unanswered. Not out of moral laziness, shirking of duty, or lack of commitment, but perhaps out of the sheer overwhelming magnitude of what we are up against, the brute force of it, and our keen awareness that our best and brightest tools, our pens and paintbrushes, do not seem to be much of a match for their swords, slings, and arrows. Yet somehow we must find a way to face off against these menacing forces of intolerance, or we will surely find the whole palace—and everything we value in it—burned to the ground.

It is in these matters where Chaos in the Palace makes me passionate, makes me angry, and where it makes me afraid for us. Maybe for all our civilization, our learning, our culture, our erudition, it is the monkeys, the birds, and the trees that live better than we do. But if those things—our learning, our criticality and questioning, our creativity, our tolerance of difference, and our will toward empathy for Others—that we thought were our greatest strengths cannot save us from the violent chaos now being unleashed upon the world, then who are we?

Without those things we become the mute monkey in its victim/refugee incarnation. Indeed, we allow our culture, our civilization, and our learning and reason to be incinerated at all of our peril. As weak as they now seem to be in the face of so much unreasoning violence, these “weapons” (reason, words, art, creativity, humanism, secularism, tolerance) are still the best we have, and most importantly, they still remain the best of what we are when we are at our best. Maybe distractions, like the market, our vanity, appeasing social flattery, and fraternizing, have gotten the better of us and vitiated our best hopes in art, emptying out of it the vitality and power that could allow it to save us. The balloon dog is no match for ISIS rampaging through Syria and Iraq, or the RSS (the national paramilitary wing of the ruling BJP party) in India, or Donald Trump in America, and a glamorous pop-art Marilyn isn’t going to offer us a new vision for humanity.

So what is left? What power does art still potentially have? We know that the Fedora Man admits to his complicity, but here he isn’t the Evil Orientalist anymore. Here he becomes a kind of Everyman. He is us. He gets caught up in the party, he navel gazes, he gets distracted by the glitz, he takes his own small role a bit too seriously, and in the end he is under a storm cloud that is following him everywhere, and no umbrella is going to be big enough to hold back all that rain. In the end, he feels desperate; nearly vanquished in the face of violence, he’s ready to give up and admit his impotence. Yet perhaps he does this for us. Perhaps he allows himself to be the fall guy who shows us where this kind of capitulation and quiescence can only lead. Maybe he shows us because he wants us to grow indignant at him for giving up so easily, get riled up, and be unwilling to do the same. Maybe, just maybe, he is staging another provocation and hoping we will respond with a call to arms. One that we can call our own, one that we are ready to take responsibility for—and who that “we” is will be determined by how we respond to the crisis, to this chaos, and how determined we are to save our palace.

How can we reclaim what is righteous and powerful in our letters and arts, in our tolerant humanities, in our fragmented left-behind-ness, in such a way that will allow us to fight without losing the very humanity we are fighting for in the process? This suite of paintings doesn’t offer an ideological answer or a quick fix to this question, but the chaos in our palace most certainly compels us to ask ourselves these questions nonetheless and to acknowledge their burning urgency.

We must acknowledge that this crisis at hand takes place within an environment of xenophobic, nationalistic persecution and censorship that is growing worldwide. This is the actual terrain on which we must now wage a new kind of war, and we must hone our cultural weapons for the struggle, the only kind of weapons we have at our disposal that we are willing to use. Not swords, guns, and lathis, but rather ideas, images, culture, and critical thinking. How to make them no longer impotent in the face of violence is our challenge. To me, this is the most important kernel of truth in the fruits offered within this suite, and it is a truth that can crack your teeth when you bite down on it.

Waswo X. Waswo and R. Vijay, Chaos in the Palace, 2015. Suite of 18 miniature paintings, gouache and gold on wasli. Courtesy of the artists.

Ecological political theorist, art critic, and curator Maya Kóvskaya (PhD UC Berkeley, 2009) has authored, co-authored, edited, translated, and contributed to many books and articles on contemporary art as it intersects with the political, cultural, and ecological. She has curated many exhibitions in India, China, and abroad, and is art editor for positions: asia critique (Duke University Press). She is currently writing a book on art and the Anthropocene in India, and another on contemporary Indian photography. For more see www.mayakovskaya.com and www.mutualentanglements.com.