Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952–1982, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, February 12–July 2, 2023. © Museum Associates/LACMA.

Historical surveys of computer-based art on the West Coast have been rare and largely driven by dedicated curators of media art in institutions like the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Beall Center for Art & Technology at the University of California, Irvine. While contemporary art museums in New York, including the Whitney and the New Museum, have put significant resources into surveying and historicizing digital art, Los Angeles institutions have paid far more attention to digital advances in film and entertainment than to asking what the onset of the technological age has meant for art and for artists. Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952–1982 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) fills this gap by connecting systems-based Conceptual art with computer-based art and graphics, which include digital imaging, weaving, computer music, coding, typography, and animation. With several more exhibitions slated to address the evolution of computer-based art scheduled for the 2024 iteration of the Getty-led PST Art initiative, which is focused on art and science, Coded arrives at an opportune time to bring the Los Angeles art-viewing public up to speed in advance of the conversations to come.

Coded begins from the predictable and limiting framework of filtering digital art history through a Conceptual art discourse. Charts, grids, punch cards, and flowcharts figure as visual motifs throughout the exhibition. Sol LeWitt’s iterative Incomplete Open Cubes (1974/1982) links systems art produced with computers using early graphic modeling environments to Conceptual art’s geometric experiments with sequence, repetition, and perception. Manfred Mohr’s algorithmically generated video Cubic Limit (1973–74) and Siah Armajani’s video To Perceive 10,000 Squares in 6 minutes and 55 Seconds (1970), both created shortly before LeWitt’s sculpture, execute similar operations of seriality and repetition using the cube shape but within the time-based environment of the screen rather than the spatialized phenomenological environment. Despite this conventional framing and a pronounced gender imbalance in favor of men in this exhibition, several important women and a few artists with ties to Latin America are foregrounded. I will focus my attention on these artists who have been leaders in the digital art field for many decades.

Many works on view in Coded infuse systems logic with an element of contemporary critical thought, which means deemphasizing imagery created by designers and researchers in favor of experiments in computing as artmaking undertaken by trained and established visual artists. Rather than acquiesce to the hardware fetishism that characterizes the exhibition’s introductory gallery or the aesthetics of mass reproduction that conditioned graphic design during this period, I am looking for the personal, the interpretive, and the affective—the human element that is retained even when the artwork is made using automated systems. These characteristics are distinctly apparent in the embodied technological practices of artists in the exhibition who are women, particularly the work of Sonya Rapoport, Beryl Korot, and Barbara T. Smith.

LACMA has a long history with media arts. Maurice Tuchman’s foundational Art and Technology Program (1967–71) was reinvented as the Art and Technology Lab in 2014 to produce artist commissions and public programs. Even so, LACMA, like other Los Angeles museums, does not maintain a curatorial department dedicated to media arts collections, and none of the city’s collecting institutions have specialist curators of media arts on their curatorial staff. Coded was organized by LACMA’s Prints and Drawings curator Leslie Jones, and it places heavy emphasis on computer art as a print-based medium. The exhibition was inspired by a 2014 gift of computer drawings from the late 1960s by hard-edge painter Frederick Hammersley that represent volumetric forms in an Op art style composed using ASCII text characters printed on tractor-feed computer paper (sheets of paper bearing perforated borders that were used in dot-matrix printers).

Hammersley made these drawings on an IBM 360/40 mainframe computer and 1403 impact printer using the Art1 software developed for artists by engineer Richard Williams.1 At present, institutions’ departments of prints and drawings and photography have taken the most interest in computer-based art. This fact underscores the difficulty of absorbing digital art into an object-based collection paradigm that has scarcely adapted to twenty-first-century conditions. If computer art, like drawing, is the fruit of a direct conduit between the creative mind and the tool (or hand that wields it), then categorization within prints and drawings collections makes sense. Many of the artworks on view would be considered monoprints because they are unique objects not rendered by hand. But this definition does not cover all of digital art. More importantly, the lack of sufficient support for durational and interactive art at the institutional level means that digital art is typically misclassified within museum collections. Action in the age of computing ought not to be reduced to simple mark making, corralled within the province and the privilege of the human.

Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952–1982, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, February 12–July 2, 2023. © Museum Associates/LACMA.

The first generation of American artists who learned to code, including Hammersley, Rapoport, Vera Molnár, and Manfred Mohr, were trained as abstract painters in the mid-twentieth-century tradition. They began with FORTRAN (1957), IBM’s first commercially distributed programming language that “began the process of abstracting software from the hardware on which it ran,” thus allowing artists to translate simple computer code into visual forms more adeptly.2 As painters, these artists integrated the tools of painting into embodied gestures that they sought not to recreate but to emulate within the different terms of embodiment that the computer proposed. In coding, these artists found a way to express their ideas using ASCII text, algorithms, and databases to generate images that aligned with Abstract Expressionist formal values of creating imagery that retains the shape of the tool used to make it (whether a hand tool such as a brush or a computer printer) while allowing the individual subconscious or collective unconscious of the artist to guide the execution of the work. The rationalism of computer programming offered a new formal structure within which these artists could invent. But the novelty of computer programming meant that their works, however guided by the study and practice of visual art, have only recently been accepted as art by institutions such as LACMA.

Rapoport was one such artist who adapted the psychoanalytic and introspective values of Abstract Expressionism to digital art using FORTRAN and other methods. Between her discovery of computer-based practices in the early 1970s and her passing in 2015, she was quietly influential on a generation of digital art feminists in California, including myself. For Rapoport, who in 1949 was one of the first women to receive an MFA degree from the University of California, Berkeley, computer-based art became a productive site for interdisciplinary inquiry. Before we had terms like “research-based practice,” Rapoport was mining scientific research as source material for associative visual works that prefigured the hypertextual systems of the Information Age. In the 1960s, she was painting on found fabrics using a symbolic language she dubbed “Nu-Shu,” in works that anticipate the feminist Pattern and Decoration movement that would follow in the mid-1970s.

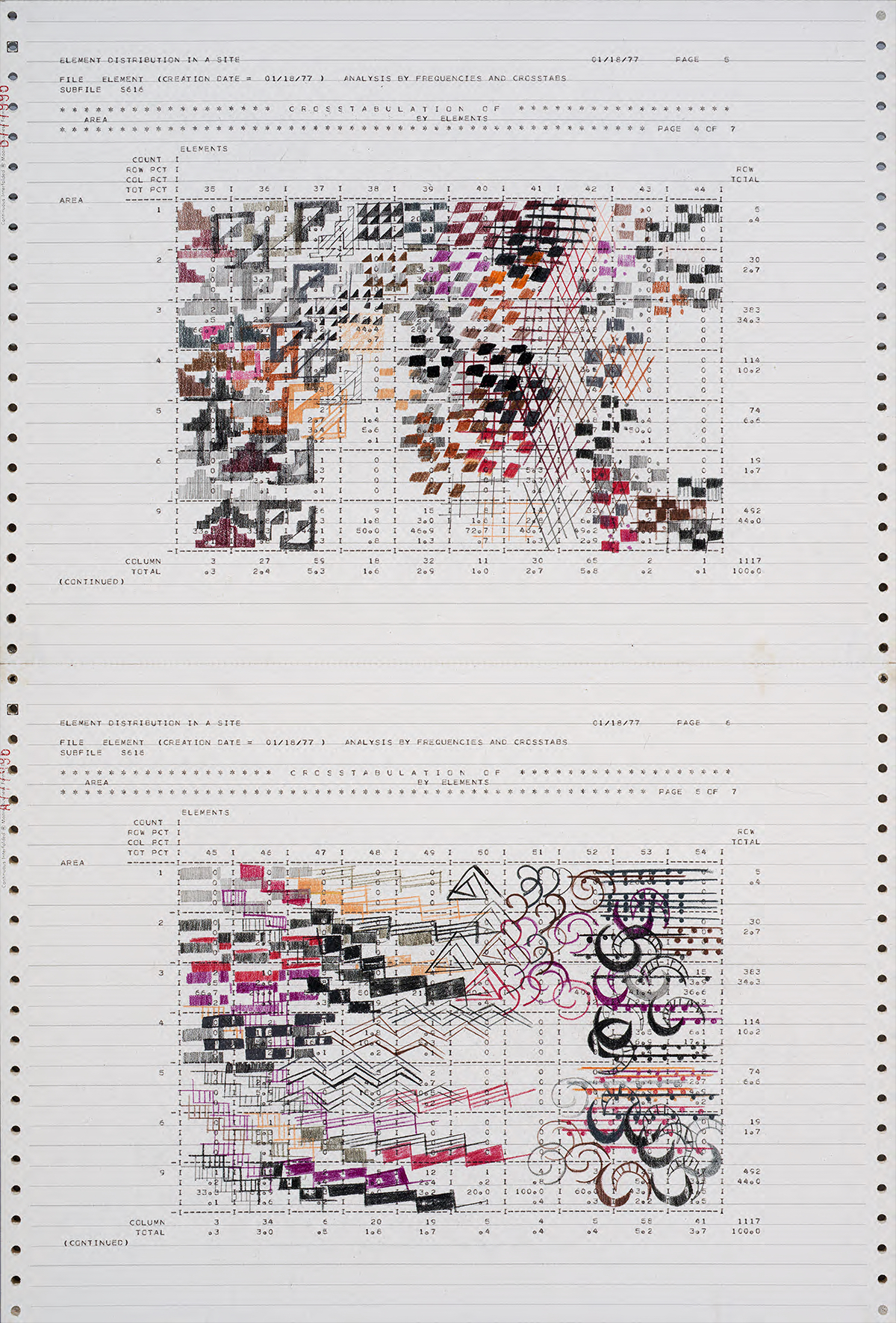

In 1970, Rapoport purchased an architect’s desk secondhand. Inside, she discovered a collection of survey charts3 that had been used in the building of the Snake River dams in Idaho, including one near the Minidoka detention camp where Japanese Americans were imprisoned during World War II. From these surveys, she produced the Survey Chart Drawings, which introduced bold color and curvaceous line to the rigid maps in a collision of sensuousness and order that would come to characterize her data-based works. The works convey Rapoport’s empathy for the Minidoka prisoners, which was informed by her Jewish identity. Motifs from the “Nu-Shu” language, including an abstracted uterine shape, globes, kidneys, and orchid-like flowers, introduce organic forms and colors that obscure and embellish the black-and-white chart data. These connections are not overt in this series, which precedes the Anasazi Series (1976) on view at LACMA by about five years. But we can already see her interest in intuitive symbology that relates affectively and historically to the quantitative data that the charts represent. In Anasazi Series, she color-codes the data into interlocking triangles that resemble the patterns described in codified form. Craft and computing are linked visually if not methodologically in this work; in other such works, she introduced thread in order to further emphasize that relationship.

Rapoport’s Anasazi Series grew out of her collaboration with anthropologist Dorothy Washburn. Washburn was a specialist in the pottery of the southwest Pueblo peoples, including the Anasazi, who were a presence in the Upper Rio Grande Valley from 1500 BCE to the thirteenth century CE. Washburn had been correlating pottery shards found at different sites throughout the region to determine the relative age of settlements that archaeologists had unearthed. Using computerized mathematical analysis, she had published a book about these correlations that included data visualization drawings by Sarah Whitney Powell and drew conclusions about interactions between different Indigenous encampments based on symmetrical analysis of designs on the pottery shards. Rapoport used the symbols from Washburn’s book as the basis for her visual responses to the data, which are both factually and emotively oriented, as she uses color and shape to reintroduce the artist’s hand into these computerized charts that record the trajectories of handmade artisanal and cultural objects. In Rapoport’s artist’s books, she used photo transfer and drawing to incorporate her own photographs and biographical elements as well as news and anthropological photos into the data sets. The works hang in accordion-folded skeins of tractor-fed paper: objects that are simultaneously drawings, screens, and books. The resulting computer printout “books” are attempts to render the data as humanly and lovingly as the archaeological remnants themselves were made. This is not just information, this is culture.

Sonya Rapoport, Anasazi Series, Folio II, detail: pages 4–5 of 15, 1977. Prismacolor, graphite, colored type, and dot-matrix print on computer printout paper, 15 x 165 in. Collection of Los Angeles County Museum of Art. © Estate of Sonya Rapoport.

Anasazi Series was shown at Harvard University’s Peabody Museum in 1978, which is the same year that Rapoport began cataloguing her shoes using a system derived from the correlative systems the anthropologists were using to study the past. Bonito Rapoport Shoes (1978) was a computer printout book that turned the anthropological lens toward the observer in a manner similar to what Russian formalist art critic Viktor Shklovsky describes as ostranenie (defamiliarization),4 an artistic posture derived from Tolstoy in which the artist is “making the habitual strange in order to reexperience it” through artistic gesture.5 Rapoport would turn the lens toward the audience again in her interactive installation Shoe-Field (1982–89), which is presented in Coded as a large black-and-white print in a frame on the wall, a single floor tile from the installation, and some photographs from the original performance under a vitrine. When Terri Cohn and I curated this work as an interactive installation, the way it was originally shown, as part of Rapoport’s exhibition at Kala Art Institute in Berkeley in 2011, we invited viewers to stand on the floor tiles and document their own shoes, while the printout showing patterns in participants’ preferences hung as a large scroll pinned to the wall that draped all the way to the floor. The floor—the location of shoes, the realm of the feet—was emphasized in the way Rapoport used the space. When she would invite visitors to her installations to document their shoes, the result was a quantitative document of qualitative information about people’s affective choices, tastes, and self-construction.

Rapoport’s trajectory is instructive because the evolution of her work and its reception follow the lineage that Jones has set out to describe in Coded, originating within the established frameworks of mid-century visual art practice and branching out into systems-oriented and information-based works as the Age of Computing gained momentum during the crucible years from 1952 to 1982. Rapoport’s work connects longstanding craft technologies with contemporary technological innovations, which is a theme in Coded that this essay will explore in further detail.

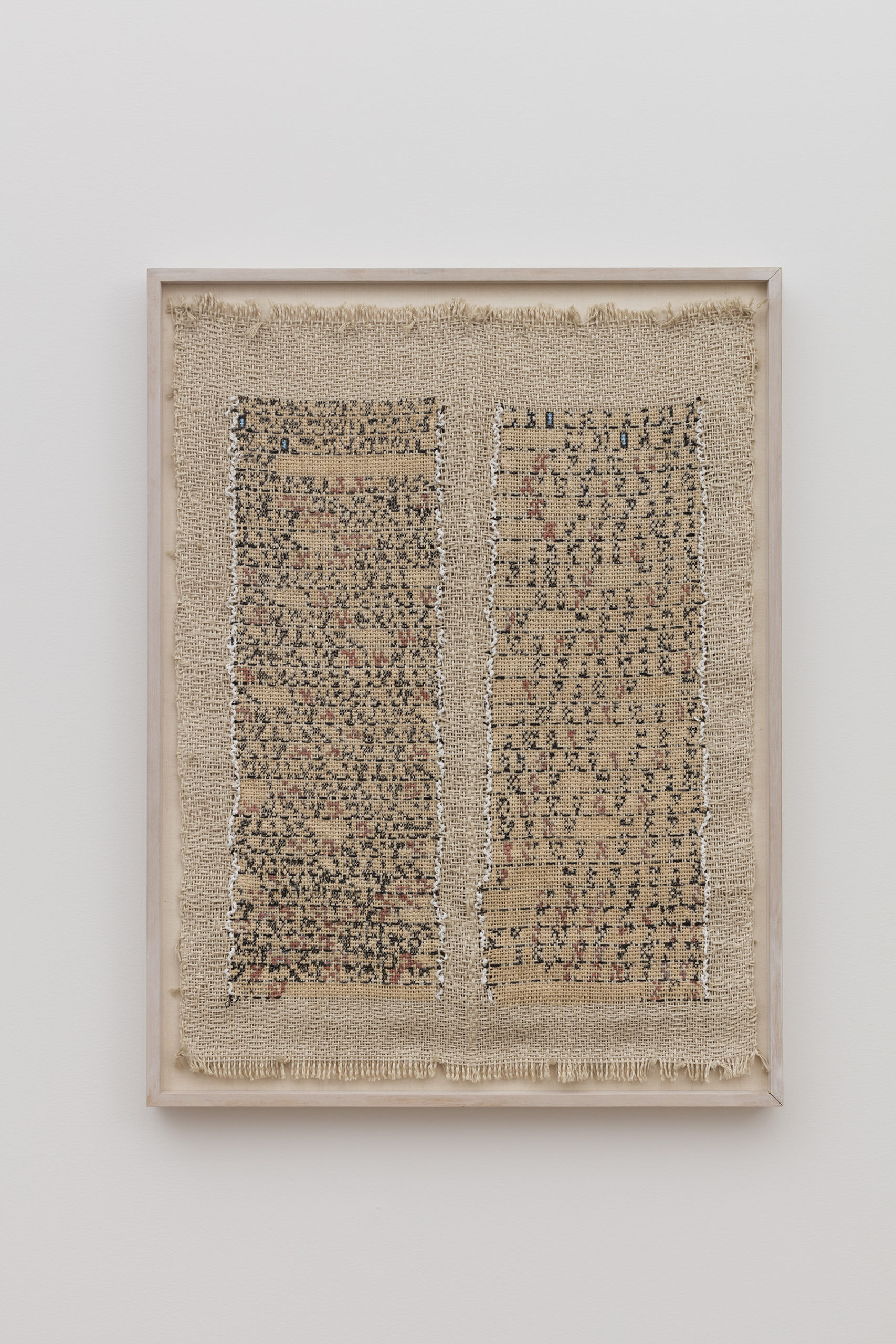

Another notable woman in a male-dominated field is Beryl Korot, who was a co-founder and co-editor of Radical Software, along with Phyllis Gershuny, Ira Schneider, and other collaborators.6 The group and publication were historicized with an exhibition at the ZKM Karlsruhe in 2018.7 At LACMA, Korot is represented by two woven wall works, Babel 1 and Babel 2 (both 1980), whose titles reference the biblical story of a failed utopia in which all of humanity could be mutually understood through language. The iterative and grid-like properties of computer graphics have a corollary in the realm of craft through the technology of weaving, which like computer graphics is rooted in the association of a single color with each square on a grid.

Beryl Korot, Babel 1, 1980. Acrylic on hand-woven linen, 30 ½ x 23 x 2 ½ in. Courtesy of Beryl Korot and bitforms gallery. Photo: Kathleen Richards.

Korot’s association of computer code with weaving is intuitive and associative. The weavings on view were created on a handloom and not by a punch-card-guided Jacquard loom, but the connection between weaving as handicraft and computer graphics is not simply metaphorical. The design of the Jacquard loom inspired the “Babbage Engine,” the first theoretical computer model, and prefigured contemporary AI discussions by putting skilled human weavers out of work. Industrialization has both elevated and complicated the living standards of the globe. Korot’s works posit that the contemporary solution to the problem of the biblical ancients who sought and failed to establish the first cross-cultural language may be computer code, which is translatable through mathematics. Or is code, like English, another Western-imposed standard that the global majority has no economic option but to learn?

Hungarian-born artist Vera Molnár recognized that artist Paul Klee’s interest in progressive variations of color, line, and shape was consonant with the frameworks of computer logic. In a series titled À la recherche de Paul Klee (1970), she used iterative computing to generate images that distributed marks equitably across a grid based on her input parameters.8 Her process was an outgrowth of the early twentieth-century art movement Dada’s emphasis on chance as a variable that complicates the artist’s intention. Molnár’s works depict the abstract geometric forms that underpin visual representation, and they resemble some of Klee’s abstract experiments with color and line. In contrast to contemporary anxiety about the AI image generator Stable Diffusion’s capacity to reproduce the aesthetic signatures of famous visual artists on command, Molnar takes the reductive visual strategy of Klee as a conceptual parameter that doubles as a computing instruction for her own, original work. Like the artist Elaine Sturtevant, who remade artworks by famous male artists, Molnar’s gesture implicitly destabilizes the idea of artistic genius.

Few of the artists in Coded hail from outside the United States and Europe, and those that do, like the Chilean Juan Downey and the Korean Nam June Paik, are historically regarded as American artists today, as they spent most of their mature careers based in the US. Brazilian artist Waldemar Cordeiro, whose work is included in Coded, was born in Italy, which likewise points to the fact that artists working in any medium who live and work exclusively in Latin America, Africa, or Asia are rarely noticed by US museums. Cordeiro is represented in the exhibition by the computer-generated image The Woman Who Is Not B.B. (1971, printed 1973), which uses text characters to build a dimensional representation of an Indigenous woman of the Amazon. Like many Brazilian artists dating back to the 1920s, Cordeiro represented Indigeneity as a trope of Brazilian identity—despite not sharing that identity himself. Cordeiro’s daughter Analívia Cordeiro is also represented in Coded with M3x3 (1973), a ten-minute black-and-white video in which the artist and eight other women occupy nine points on a grid and move in synchronization. Their abstracted figures approximate a digitized understanding of embodiment and anticipate motion capture data that is used in contemporary animation.

The Chilean artist Juan Downey, born twenty-five years after Cordeiro, problematizes the association between white, Westernized Latin Americans and Indigenous culture that many artists of the era took for granted. Like Korot, Downey was associated with Radical Software, though less centrally. He was also connected with the French collective GRAV (Groupe de Recherché d’Art Visuel) along with the aforementioned Molnár. Both Downey and Molnár are represented in Coded with works that orient to the concerns of official art history. Downey’s A Research on the Art World (1970) is presented in three parts: Dear Artist, Dear Collector; Answers Given By Artists; and Answers Given By Critics. Each drawing is a visualization of survey data collected from artworld insiders whose language and systems are typically inscrutable to outsiders. In Dear Artist, Dear Collector, Downey reproduced the separate questionnaires he had provided to artists and to collectors, below which he drew graphing lines in red and green to represent the responses of collectors and artists, respectively. In Answers Given By Critics, a graphing line highlighted in yellow shows the responses of art critics to the question “Who would you give more power to in the art museum structure?” The options offered are “art historians,” “artists,” “art students,” “collectors,” “dealers,” “general public,” “museum directors,” and “trustees.”

Downey’s methodology relates to Hans Haacke’s MoMA Poll (1970), which was part of the Museum of Modern Art’s Information (1970) exhibition, and Haacke’s installation News (1969/2008), included in the Jewish Museum’s Software exhibition of 1970 and represented in Coded. MoMA Poll included two transparent “ballot boxes” shaped like sculpture pedestals. The artist presented museum visitors with the question “Would the fact that Governor Rockefeller has not denounced President Nixon’s Indochina policy [i.e. US involvement in the Vietnam War] be a reason for you not to vote for him in November?” “Yes” votes were directed to the box on the left while “No” votes were placed to the right. News is a live feed of news dispatches over a teletype system, printed out on continuous-feed paper so that the cacophony of information is visually reinforced by an incomprehensible pile of looping paper. Both of these works by Haacke use contemporary geopolitics as the basis for a study of data as an accumulative phenomenon. Downey’s approach is less focused on the public and more concerned with the conditions of being an artist. Drawing connections to Haacke also points to the limitations for artists of presenting information-based work in museum exhibitions, in that both Information and Software made arguments similar to the case that Coded puts forth over fifty years later. Downey’s focus on art as a mode of labor perpetuated by an ecosystem of artists, critics, and collectors anticipates the concerns of the present as expressed by data-focused arts collectives such as WAGE and the Los Angeles Artists’ Census.

Hans Haacke, News, 1969/2008. OKI microline 590N 24 Pin Printer with newsfeed on table, roll of paper, dimensions variable. © Hans Haacke / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Courtesy of the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

To address a few final points concerning automation and inclusion, I will turn to the work of Stanley Brouwn and Barbara T. Smith. Brouwn’s artist’s book 100 this-way-brouwn-problems for computer I. B. M. 360 model 95 (1970) predicts our reliance on GPS to navigate our physical world and our quantified selves as encompassed by step counters and other biometric measures. Brouwn attempted to remove intuition and individuality from the practice of art in favor of a “post authorial” approach.9 Automation through the computer was one of many methods he utilized to realize this goal. The book is constructed according to a conceptual algorithm designed by Brouwn: “‘show brouwn the way from each point on a circle with x as centre and radius of [ ] angström to all other points,’ repeated on each verso, for one hundred times, with a variation of the number indicated before the term ‘angström.’ Every time, the number increases its value of 1 unit. Beside the margin where the first ‘show brouwn.’ is printed, is also indicated the mathematical value of 1 ‘angström’: “1 ‘angström’ = 0,000 000 01 cm.”10 The small square book with instructions written on each page in a black sans serif type resembles a manual. Here the framing of the history of computer art within Conceptualism is thoughtfully linked to the rules-based nature of coding and programmatic execution.

At the time, the computerized technology was insufficient to the tasks Brouwn put to it, which resulted in a level of absurdity and futility that tracks with Brouwn’s dematerialized, subtly Afropessimist approach. The landscape around us takes on a defamiliarized aspect, the local streets rendered new and strange. Because the Suriname-born Brouwn, who was active in the Netherlands during his lifetime, rejected critical interpretations of his work, there is little to go on from scholars and critics, who primarily describe his practice. The artist himself offers minimal explanation, only simple prompts for thought or action. Brouwn is never present in his works, the way that race is never present in Conceptual art, which in 1970 was widely held as ideologically neutral. Brouwn cleared the way for an artist like Charles Gaines—who appears in Coded with Walnut Tree Orchard, Set B (1975), one of his signature gridded trees derived from branching algorithmic calculations—to maintain an Afropessimist approach to Conceptualism and data. Brouwn’s defamiliarized approach to the role of the artist embraces the Situationist International motto ne travaillez jamais (never work) and the implicit bias of data, which scholars such as Ruha Benjamin have documented and critiqued. Unlike Gaines, who explicitly references forms associated with Black death, such as chains and trees, Brouwn takes a position closer to that of Warhol, who identified with the anonymity of the computer over the identity-forward role of the immigrant artist as a position from which to navigate the swells of Western capitalist culture.

For Barbara T. Smith, who is one of very few women represented in 1970s computer art exhibitions, the practice of art is an ongoing practice of self-liberation from the constraints of contemporary capitalist life. I Am Abandoned (1976) cheekily inserts female sexuality into the sterile environment of the computer lab by introducing a woman performer dressed in white, on whose body is projected the image of Francisco Goya’s Naked Maja (c. 1795–1800), the Spanish realist painter’s notoriously sensual nude painting thought to depict the Duchess of Alba. Documentation of this performance is included in Coded in the form of photographs of the event and Smith’s script, which is based on a 1972 conversation between two chatbots located on opposite coasts. The chatbot at Massachusetts Institute of Technology was programmed to speak from the perspective of a psychotherapist using the DOCTOR protocol coded for ELIZA, while the other, at Stanford, was modeled on a paranoid schizophrenic using PARRY,11 a chatbot designed to compete with ELIZA in beating the Turing Test.12 Smith’s performance restaged their conversation as alternating projected text with a live “computer operator” and a female “muse,” who grows tired of the computer operator’s obsession with the chatbots and tries to attract his attention through seductive measures. Smith problematizes the role of women in artistic and technological settings while anticipating the collective loss of reality that we experience today as stochastic language models replace human interactions in a variety of settings.

For Smith, woman is constrained by the role of muse, as her beauty and physicality are celebrated in place of her intellect. Smith challenges the disembodied culture of the computer age while arguing for female subjectivity and embodiment as essential characteristics of digital life that have been underexamined. Says Smith of her entry into the contemporary art world in the 1970s after raising children, divorcing, and completing her MFA at the University of California, Irvine, in 1971 at the age of forty: “It was still a man’s world, and I didn’t yet know how to make it work for me.”13 Smith’s work introduces the question of women’s constructed role as the products of men’s technologies (think of Pygmalion’s “creation” of Galatea) as opposed to their biological role as creators of the species or their ontological role as shapers of the mind.

In decades of artistic practice presented concurrently with Coded in solo exhibitions at the Getty Research Institute and The Box, Smith has shown that her interest is in exploring and fulfilling the spiritual role of women while liberating herself and others from social or biological determinism. Even so, those limitations have impacted her, such as when she submitted a proposal to the Osaka ’70 pavilion curated by Experiments in Art and Technology (EAT) but found her work rejected on a technicality she did not consider legitimate.14 A related interactive work, Field Piece (1968–72) was rejected from the Art and Technology program at LACMA but was completed despite the artist’s financial hardship.15 Field Piece is a “field” of dozens of fiberglass tendrils that illuminate like dendrites at the ends of human neural cells. In Smith’s exhibition at the Getty, sixteen surviving examples are installed against a mirrored backdrop that approximates the artist’s vision of infinity. Smith activated the original installation with dance and naked walk-throughs that captured the sexually free spirit of the era.16 Smith’s emphasis on free expression and embodied pleasure coexists with an interest in art and technology that has been consistently ambitious yet underrecognized until now.

Choreographer Deborah Hay, one of the few women who participated in EAT events, appears in Coded, but not as an artist. Instead, she is present as the model for the first “computer nude,” in Leon D. Harmon and Kenneth C. Knowlton’s Studies in Perception I (Alpha Serendipity) (1966). A related image in the collection of the Buffalo AKG Art Museum, Computer Nude (Studies in Perception I) (1967) is billed as “the most widely circulated early artwork made using a computer.”17 As an artist, she collaborated with Billy Klüver and other Bell Labs scientists on “9 Evenings: Theater and Engineering” in 1966. Here, Hay agreed to pose for a photograph in the posture of a reclining nude, which engineers Harmon and Knowlton translated into a computer-generated image using vector graphics derived from the form of the Greek letter Alpha to denote elements of electronic circuit diagrams and mathematical symbols.18 The resulting image is included in Coded as a benchmark in graphic imaging innovation, though its regressive aesthetics hew to a Neo-Classical expectation that the nude female figure is the value-form through which the concept of “art” is defined. This contrasts with Hay’s own work as a choreographer, including her performance Solo (1966) for “9 Evenings,”19 which is innovative precisely because it combines unfamiliar aesthetics from Japanese Noh performance traditions with Western modernist staging and affect, thereby defamiliarizing our relationship to performance and the body. Meanwhile, Harmon and Knowlton’s Alpha Serendipity at LACMA reinscribes two old ideas. First, art is a smokescreen for erotic titillation. (“[Bell Labs executive director of communications systems research Edward E. David Jr.] was delighted with the photograph, but several members of Bell management felt the giant nude was inappropriate.”20) Second, women are the “ghost in the machine,” the metaphysical essence that emerges from systems designed and controlled by men. Whether Hay’s own artistic contribution is absent from Coded because of her gender or because a show organized through Prints and Drawings didn’t factor her in as a performer, her exclusion as an artist feels like an omission. To paraphrase the Guerrilla Girls, do women have to be naked to get into the museum?21 (Or onto the internet?)

Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952–1982, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, February 12–July 2, 2023. © Museum Associates/LACMA.

Coded narrates art’s relationship to technology from the perspective of the latter’s evolution, with data visualization and graphic design made with the express purpose of conveying information given space and consideration equal to artworks that raise critical questions about how and why we use information in the digital age. Certainly, each of these realms of visual innovation in computing has been impactful in its way. But the question of what constitutes art in the computer age is never fully addressed. One key area where questioning remains essential is that of the body’s relationship to digital space, which is only becoming closer and more integrated as technologies advance. The artists in Coded that I have discussed here offer some clues as to how we might approach our cyborg future and a template for the adoption of computer technologies within the arts. Such anticipation is thrilling, and sometimes chilling, to observe in artworks going back forty to seventy years. Yet, it is insufficient to address the evolution of visual or performance art forms due to technologies that were not yet well understood or widely available beyond the white, educated middle class. We may need to look ahead another forty to seventy years before we can say exactly what has happened to art since we entered the age of computing.

Anuradha Vikram is a writer, curator, and cultural organizer based in Los Angeles. They are co-curator of the 2024 Oregon Contemporary Artists’ Biennial in Portland and guest curator of the 2024 PST Art exhibition Atmosphere of Sound: Sonic Art in Times of Climate Disruption at UCLA Art Sci Center. Vikram’s books are Use Me At Your Own Risk: Visions from the Darkest Timeline (X Artists’ Books, 2023) and Decolonizing Culture (Sming Sming Books, 2017). They are a member of the editorial board of X-TRA.