There are only so many ways to open up a channel of communication with a stranger. What does it mean when someone begins with the words “I must first apologize…”? This demure utterance serves as the title of an elaborate exhibition by Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) List Visual Arts Center, where the artist-duo reveals how apologies often disarm strangers in order to defraud them. Picturing the practice of online spamming, the artists employ a heuristic the anthropologist George Marcus once famously called “follow the thing,” whereby everyday physical phenomena—an utterance, a material, an object under our noses—mediates a set of intertwined and inevitably geo-politicized social relations.1 This technique has achieved cachet along the global biennial and contemporary museum circuit as a result of its dominance within the humanities and social sciences. In fact, if “follow the thing” were not so persuasive, we might call the heuristic itself a kind of proliferating spam.

In the MIT exhibition, the familiar object is the deceptive message that shows up in your email inbox, the one claiming to make you rich and perpetrating advance-fee fraud. As the media scholar Finn Brunton describes in his erudite history of spam, “Nigerian Prince” frauds and others like it are generically patterned on centuries-old Spanish Prisoner confidence schemes. Swindlers lure their marks by claiming they are aristocrats with large fortunes holed up in Spanish jails under false pretenses. Since the turn of the millennium, spammers have had to adapt the romantic motifs of exotic locales, damsels in distress, and covert rescue plans that inhere in the genre to online platforms and less gullible victims.2 The content of spam messages is far-fetched to be sure, but the processes of social and technical adaptation that undergird them belie truths about the relations between spammer and spammed. These relations can be read metonymically as microcosms of exchange between core and peripheral processes in the modern world system.3 The online plea by a “diplomat” hoping you will funnel large sums out of the country speaks to the expropriation of capital and natural resources in petro-states worldwide. The scam-baiting subculture (an anonymous online community that outwits and embarrasses spammers) is based primarily in Reddit forums in the United States, United Kingdom, Netherlands, and Germany. When these scam-baiters dupe spammers in Nigeria and the former Soviet Bloc, they hypostasize the kinds of transactions that allow surplus value to flow from weak countries to stronger ones. And when scam-baiters coerce spammers into posing in drag, donning “ethnic” garb, or performing invented “primitive” rituals, they perpetuate the kinds of “ethnic marketing” and late-orientalist fantasies that continue to naturalize the inequality built into global markets.

Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, The Trophy Room (detail), 2014. Installation view, I Must First Apologize…, MIT List Visual Arts Center, February 19–April 17, 2016. Courtesy the artists and In Situ/Fabienne Leclerc (Paris), CRG Gallery (New York), The Third Line (Dubai). Photo: Peter Harris.

Articulating these types of metonymic connections has preoccupied scholars for decades.4 When online spammers began shaking down their marks in the late 1990s, a host of cultural anthropologists started to describe the spammers’ lived experiences as they toiled away at internet cafes across Africa and Eastern Europe. They explained the kinds of exploitative hierarchies, dire prospects, technical assemblages, and historical tragedies that produced spamming as an enterprise.5

Their research flourished as a strategy we might call “Material Infrastructure Studies” (MIS), achieving success through the way academics and others who used it leveraged concrete examples—water, drugs, remittances, electronics, or decommissioned cruise ships—for the purpose of justifying their research and acquiring financial and institutional support. The example cathected granting organizations, university administrations, and lay audiences alike, luring in anyone who wanted to hypostasize macro-social processes in physical artifacts. MIS found its strongest adherents in fields that privileged materiality: architecture, art history, archaeology, cultural anthropology, geography, science and technology studies, and, to a certain degree, art, where examples could be fabricated out of whole cloth. The examples performed exceptionally well; they were infinitely fascinating to describe in nearly myopic detail, legitimating close-reading techniques, but they also globetrotted, mirroring the expansionist missions of neoliberal academic institutions and their entrepreneurial scholars.

I Must First Apologize… seems to conform to the MIS paradigm: spam is its concrete example, its discourse readymade.6 The question for the critic then becomes two-fold: Where is the art? And how is it operating within a pre-packaged nexus of design, research, information, and commentary? Proponents of research-driven art projects argue that artists’ archival impulses unearth suppressed histories and point to the productively unresolved way art accesses historical knowledge; detractors frown at its inevitably pedantic quality, where amateurs seem to tell less nuanced versions of stories that derive from, illustrate, or even obscure academic inquiry. Even when these positions are valid, they hardly begin to address the way artists actively transpose existing dominant attitudes and formulas for dealing with an issue—in our case MIS approaches to spam—onto the chosen exhibition format. Critics avoid considering the act of adaptation and inflection as the artwork, preferring to do away with this intermediary problem in order to think about how artists use formal means to address the stated issue directly. But Hadjithomas and Joreige are not just showing alternative histories of spam or illustrating work by scholars such as Brunton. Even when they do so, they are also preoccupied with calibrating established discourses around spamming practices with existing vanguard exhibition strategies. And this art of mutual calibration deserves critical attention.

Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, The Trophy Room, 2014. Installation view, I Must First Apologize…, MIT List Visual Arts Center, February 19–April 17, 2016. Courtesy the artists and In Situ/Fabienne Leclerc (Paris), CRG Gallery (New York), The Third Line (Dubai). Photo: Peter Harris.

I Must First Apologize has an informational style typical of factographic or conceptual art: lists, maps, printouts. The artists rekey these gestures by highlighting their indexical qualities. The form of the list is not enough; we actually have to read what it says. By opting for the legibility of their references over sheer enumeration, the artists shed the historically utopian or urgent dimension associated with earlier avant-gardes. Scrolls of paper—diminutive in comparison with El Lissitzky’s dizzying rotating newspapers from the Soviet Pavilion at Pressa, Cologne (1928), and Hans Haacke’s from the Software exhibition at the Jewish Museum, New York (1970)—present the epistolary correspondence between scammers and scam-baiters. In The Trophy Room (2014), printouts of scam-baiting “trophies”—online documents evidencing the humiliation of scammers—are affixed to concrete plinths bisected by glass sheets. The format is meant to refer to Lina Bo Bardi’s staging of Andre Malraux’s Museum Without Walls in Sao Paolo in the 1960s, which has become synonymous with the democratization of culture and Paolo Freire’s “pedagogy of the oppressed.”7 The sculptures comprising Hadjithomas and Joreige’s A Matrix (2014) are made of reticulated hemispheres laser-cut into minimal plywood cubes. The Geometry of Space (2014) is a series of mobiles that diagrams networks of spam communication through crisscrossed lines of stretched-oxidized steel. They look like three-dimensional flight plans. Each of these works borrow from the practical pedagogy of the proposal and the brief; they have the look, scale, and finish of architecture-school maquettes and informational posters that are employed by students and professors in the rest of the MIT List building on a daily basis. While the models ostensibly invoke the travel of spam across a global network, in effect, they signal an allegiance to established trends in contemporary art, whether through restaging Bo Bardi’s installation, which has gained currency in curatorial circles over the past decade, or by materializing as steel sculptures the maps cultural geographers have produced in recent years to picture global flows of labor, capital, and information.8

Across the hall, amateur actors read spam messages aloud on thirteen screens in The Rumor of the World (2014). If the lit rooms in other parts of the exhibition amount to a space of pedagogy, wherein the audience is asked to read, this darkened space is more theatrical. The installation hews closely to the rubric of docudrama installations connoting geopolitical gravitas, which have been commonplace since Okwui Enwezor’s Documenta XI. Toward the ceiling, wires cross above the installation as small blue lights overhead approximate distant cities seen from a plane at night or, more precisely, a kind of “heart-of-darkness” cyberspace—a pitch black zone for the post-colonial encounter with the spam message. But because the lights and wires are part of the equipment of the audio speakers and the monitors, they reduce the metaphoric associations of the installation to an effect of practical decision making and cost cutting. The conceit that the equipment had to be plugged in and the wires had to end up somewhere cleverly undercuts the felt-immediacy that the installation otherwise promotes. Hadjithomas and Joreige borrow from the global biennial black box/white cube video installations of the 1990s, but only in order to present the labor and research that went into compiling and assembling their show. If the artists are apologizing here, it is because they refuse to offer us the spectacle of full immersion.

Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, The Geometry of Space (detail), 2014. Sculptures, stretched oxidized steel; Scam Atlas. 3 publications; murals, chronologic drawings of 2005, 2008, & 2010. Sculptures’ diameter 31½ in. Courtesy the artists and In Situ/Fabienne Leclerc (Paris), CRG Gallery (New York), The Third Line (Dubai).

The artists use the avant-garde art of the past—factography, constructivism, docudrama, and so forth—to bathetic, pedantic, and banal ends, draining it of its affective intensity. How then do they calibrate their work to the already existing discourses on spam? In The Rumor of the World, the artists seem to vivify the typical written qualities of the spam message—an amalgam of grammatical errors and adventure plots—by recording non-professional actors who read the messages aloud. Employing direct address, they videotape the actors frontally, opposite the viewer, against a studio backdrop. The actors read the messages in a measured way that precludes us from suspending our disbelief in their performance. We are unable to imagine that they are truly spammers themselves. By highlighting the artifice of the spam prose and dis-aligning the actor and the spam writer, the artists nominate spam delivery as a kind of artful practice, something that can be done with different degrees of competence, creativity, and effectiveness. Hadjithomas and Joreige therefore restage the work of scholars, such as Brunton, who have made salient the ethno-poetic quality of spam, transposing the setting of the address from online computer interfaces to the theater of the video installation.

Tucked away in a small gallery toward the back of the show, four video testimonials play slightly out of synch with one another in the installation It’s All Real (2014). These testimonials of immigrants from Africa, Asia, and Eastern Europe residing in Lebanon provide ways of talking not about spam itself, but about the legibility, perspectives, norms, and affective attachments that go into research on the precarious circumstances of refugees, domestic workers, and laborers. Only “Fidel” turns out to be a reformed-spammer. The rest have nothing to do with the enterprise. On one level, the videos straightforwardly contribute to this research, providing vignettes of everyday routines in Beirut: adolescents at leisure, a “christotherapist” who bridges the secular/religious divide through a syncretic form of healing, and the ex-spammer at the gym. But because the testimonials are expertly edited and shot in high definition, the moments we witness appear staged, and we are conscious of the compositional decisions that went into the framing—the long takes, synched frames, and the removal of the prompt of the questioner. Thus the production quality interferes with what might otherwise be considered participant observation. The video testimonials are not exactly tokens of the interview or documentary research type found in, say, visual anthropology.

Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, The Rumor of the World, 2014. Installation view, I Must First Apologize…, MIT List Visual Arts Center, February 19–April 17, 2016. Courtesy the artists and In Situ/Fabienne Leclerc (Paris), CRG Gallery (New York), The Third Line (Dubai). Photo: Peter Harris.

Hadjithomas and Joreige’s alteration of documentation and use of non-actors for dramatic purposes corroborates a strategy that they pioneered—alongside Walid Raad, Jalal Toufic, and others in and out of Beirut—in the late 1990s in the aftermath of the Lebanese Civil War. Doctoring photographs and textual evidence, this generation invented fictional archives that seemed to dissemble official accounts while filling in historical gaps around everyday life during wartime. At the same time, their use of pseudonyms and avatars gestured towards the establishment of political agency under conditions of censorship. Yet in this exhibition, Hadjithomas and Joreige seem to play with documentary conventions for different reasons, not to dissimulate the historical record with rumor and partial information, but rather to point to the way registers of self-constraint and self-actualization are used for sentimental effect among strangers.

The subjects of these vignettes appear as actor-protagonists in public relations stories about their own lives. When we watch them play basketball, do sit-ups at the gym, or sit in softly lit interiors, we get the sense that they are expertly performing the role of the “humanized” refugee, spammer, laborer, or child-victim recognizable from the ethnographic vignettes of anthropologists researching subaltern peoples. This effect is compounded by the fact that they are named in a credits section at the beginning of the video and sometimes appear as amateur actors in the highly-staged The Rumor of the World and the loosely choreographed (De)Synchronicity (2014), which was shot outside an internet café in Beirut. The vignette at the ex-spammer’s gym, for instance, looks like an ad for fitness gear. While Fidel works out, he gives us a lesson about how spammers deceive their marks. His testimonial is an odd combination of online tutorial and a new genre of video that currently proliferates through the American criminal courts: videos that present the everyday lives of defendants in order to show them as “real” people and their “crimes” as the accomplishment of an entire community.9

Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, The Rumor of the World, 2014. Video still. Video installation, 38 HD Films, on LCD screens, 100 loudspeakers, variable lengths. Coproduced by HOME, MIT List Visual Arts Center, Villa Arson. Courtesy of the artists and Galerie in situ fabienne Leclerc (Paris) The Third Line (Dubai), CRG Gallery (New York).

Since the late 1990s, anthropologists and cultural critics have tried to move beyond simply demonizing spammers by showing the historical and political economic forces that drive their activities. Hadjithomas and Joreige, however, slightly modify this enterprise. They present these pseudo-ethnographic accounts as they become commoditized through the format of contemporary online video, that is, through projects ranging from the aforementioned defendant court testimonials and online videos about ethical consumption practices to long-form political campaign advertising. These are forms that mediate ethical stance-taking to various stranger publics.

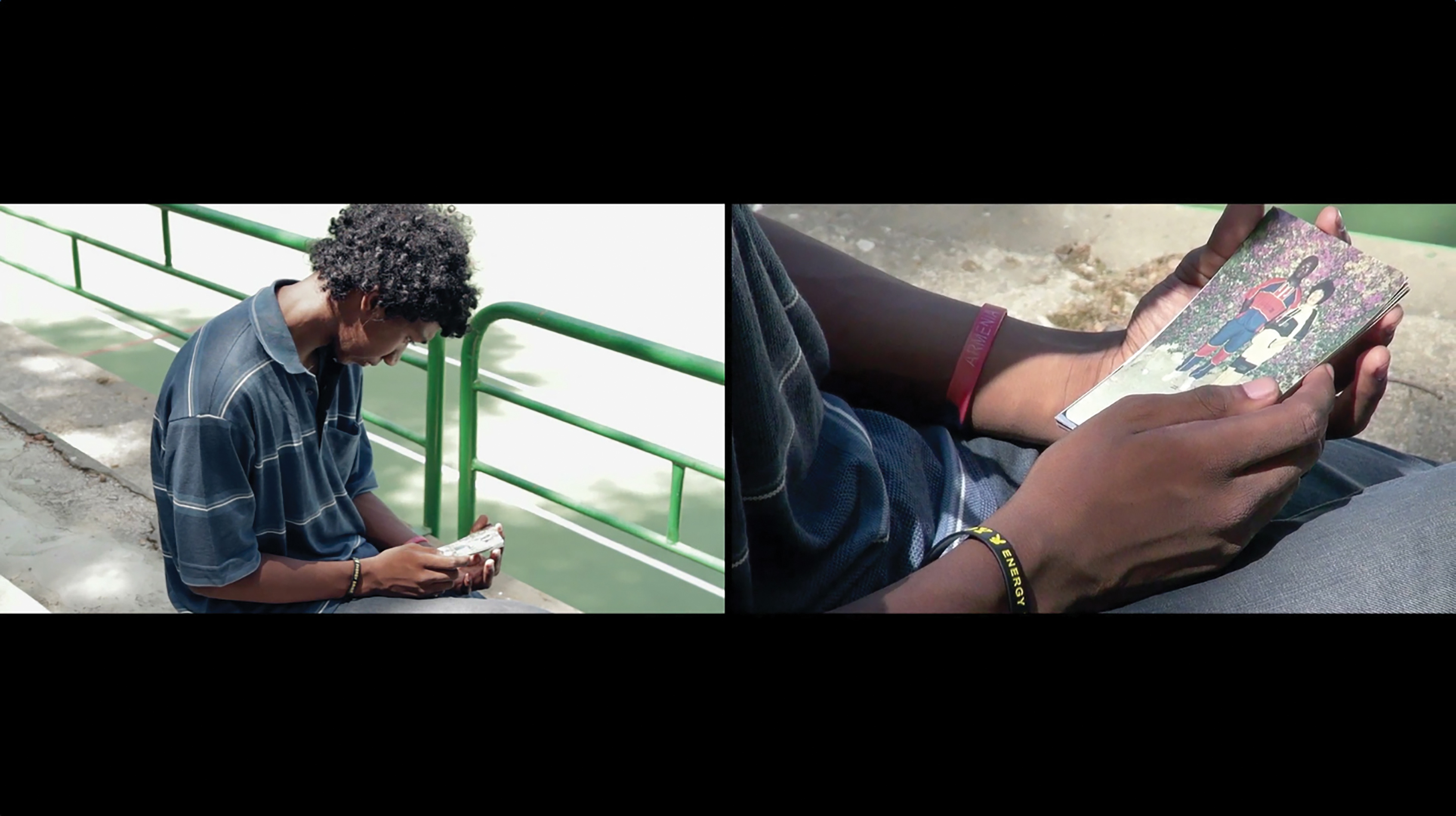

If Hadjithomas and Joreige’s work is progressive in any sense, it is because they make these forms of mediation available to the subjects of their videos. Rather than the ethnographers, cultural critics, or filmmakers who might picture refugee activities from an external perspective, they suggest how their subjects might begin to control the way their story is told. Moreover, as the artists suggest, these accounts need not be either true or false, but full of unreliable narrators and historical lacunae. Because the same character appears in multiple artworks, a non-actor acting naturally in one video installation turns out to be an amateur actor acting artificially in another. The video testimonial format of It’s All Real, in particular, allows the refugees to implicate themselves within a matrix of circumstances: within geo-political events, within kinship ties to their families and communities, and within the civil society of Beirut. The gym setting of Fidel’s full-body workouts and the domestic interior shots where a subject named Tamara looks through old family and school photographs are crucial here because they show mediated forms of domesticity and self-love, that is, contemporary models of everyday celebrity that now circulate globally online and find their way into their subjects’ repertoire for accounting for their own situated activities. Because they have chosen to use non-actors, the artists seem to suggest that their subjects too have access to the lifestyle registers of “curating” and “fitness.”

Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, It’s All Real: Fidel (Video 1), 2014. Video HD; 11.48 min. Co-produced with Fonds National des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques. Courtesy the artists and In Situ/Fabienne Leclerc (Paris), CRG Gallery (New York), The Third Line (Dubai).

So what does the apology do for the spammer who begins her message with the phrase “I must first apologize…”? Since the work of Erving Goffman on access rituals, ethno-pragmatists have argued that strangers use apologies to mark the threshold of increased or decreased contact with one another.10 Apologies allow participants with an inferior status in a community to take on the role of initiating the greeting, to manipulate it and become responsible for its entailments. Of course, the deferential apology is the result of interactional asymmetry—as in “sorry to bother you, sir”—but it is also a path to remediating the power imbalance among participants.

The artists transpose the spoken apology onto the video testimonial. And by mapping the confidence scheme onto the online video, with its routinized bio-political tropes of self-divulgence, self-management, and self-actualization, Hadjithomas and Joreige suggest that the subjects in their works have access to the everyday protocols by which strangers communicate with one another on equal footing online. It is a way of moving from the written or spoken apology of deference to the apologetic moving image. When Fidel lifts weights or Tamara leafs through her photo-album, they are drawing on the sentimental tropes of contemporary self-monitoring and presentation: Watch me work out! Watch me eat! Watch me look at pictures of my friends and family! These tropes permit the refugee-actors to enter into embodied, affective relations of confidence and trust with their audiences. In turn, they might manipulate these relations for the purposes of committing real economic fraud; they may also use them to assert their rights to the norms of politeness and civility continually denied them.

Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, (DE)SYNCHRONICITY (detail), 2014. Video still. Video installation, 4 continuous synchronized screens, 2:30 min. Courtesy of the artists and Galerie in situ fabienne Leclerc (Paris) The Third Line (Dubai), CRG Gallery (New York).

Nevertheless—despite the progressive politics of the exhibition—it turns out that the now-global online spamming practices that Hadjithomas and Joreige picture technically originate from a kind of ur-spam first entered into the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANET)—a proto-internet collaboration between MIT and the Pentagon, which Brunton describes in detail in his book. This gives the exhibition an interesting subtext, which is partially acknowledged by the curators when they write in the catalog, “Incidentally, the World Wide Web was invented at MIT in 1990.”11 The conceit that spam travels abroad and returns physically to the omphalos of the MIT campus has a kind of hagiographic function, working as a proxy-monument to the enduring legacy of the “cyber-revolution” that once transpired there. On an institutional level, therefore, the show traces the global phenomenon of spam to its source in the university and legitimates MIT’s foundational position within the history of mediatized conduct.

Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, It’s All Real: Omar and Younès, 2014. 2 synchronized HD videos, 14:50 min. Co-produced with Fonds National des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques. Courtesy of the artists and Galerie in situ fabienne Leclerc (Paris) The Third Line (Dubai), CRG Gallery (New York).

If the notion that a reputable institution would promote a nefarious activity like spamming seems farfetched, observe how, just as the exhibition closed, the director of the school’s prestigious Media Lab announced a quarter million dollar “disobedience award” at a wildly popular “forbidden research” symposium. Funded by the founder of LinkedIn, a company built on the monetization of social networks, the award was meant for “the fields of scientific research, civil rights, freedom of speech, human rights, and the freedom to innovate.”12 Here we witness the way the school socializes its members into the “disruptive” techno-libertarian values that sustain it. The call for the “forbidden”—announced in the public relations materials—marks a kind of return of the repressed, where anxieties stemming from the enormous gap between the development of technological equipment and the social interactions of the people who come to use it may resurface as art. In exploring this interstitial zone between technology and conduct, Hadjithomas and Joreige may be interpreted as uttering their own trick apology, raising difficult questions about the ideological roots and geopolitical outcomes of a technicist ideology unabashedly promoted by the institution that hosted their exhibition.

Jacob Stewart-Halevy is an assistant professor in the Art History Department at Tufts University.