To conclude “International Art English,” a widely-circulated, incendiary treatise on the language of contemporary art press releases, Alix Rule and David Levine cynically suggest that we appreciate the press release not for its bugged-out hybridizing of advertising copy and academic discourse, but for its “lyricism”: not for its sense, but for its sensuousness. Adding line breaks to an email pulled from the archive of e-flux announcements (which since 2005 has expanded by around three to five each day1), the authors reveal an almost satisfying rhythm, in which quaint yet redundant adjectives and decorative scare quotes take on new significance, afforded by the peculiar authority of blank space. Their remix begins:

Peter Rogiers is toiling through the matter

with synthetic resin and cast aluminum

attempting to generate

an oblique and “different” imagery

out of sink with what we recognize

in “our” world.2

Implied in Rule and Levine’s almost cruel sarcasm, poetry is the press release’s ultimate other. Even the article’s most severe critics maintain this opposition. Poetry haunts both Hito Steyerl and Martha Rosler’s commissioned responses to “International Art English” for e-flux journal, a publication financed by the announcements which Rule and Levine position as IAE’s paragon. Rosler mocks Rule and Levine’s use of statistical linguistic analysis by linking the practice to a history of military forensics, and by recalling an embarrassing undergraduate attempt to use statistics to decode a Wordsworth poem—a failure meant to illustrate the inadequacy of statistical analysis in all cases.3 Steyerl also pits poetry against the press release, and against Rule and Levine’s snotty language-policing pedigree. Her rebuttal ends with a call to “prefer anus over bonus, oral over moral, Satin over Latin, shag over shack.” She demands, “Let’s take a very fucking English lesson”—poetry in no uncertain terms.4

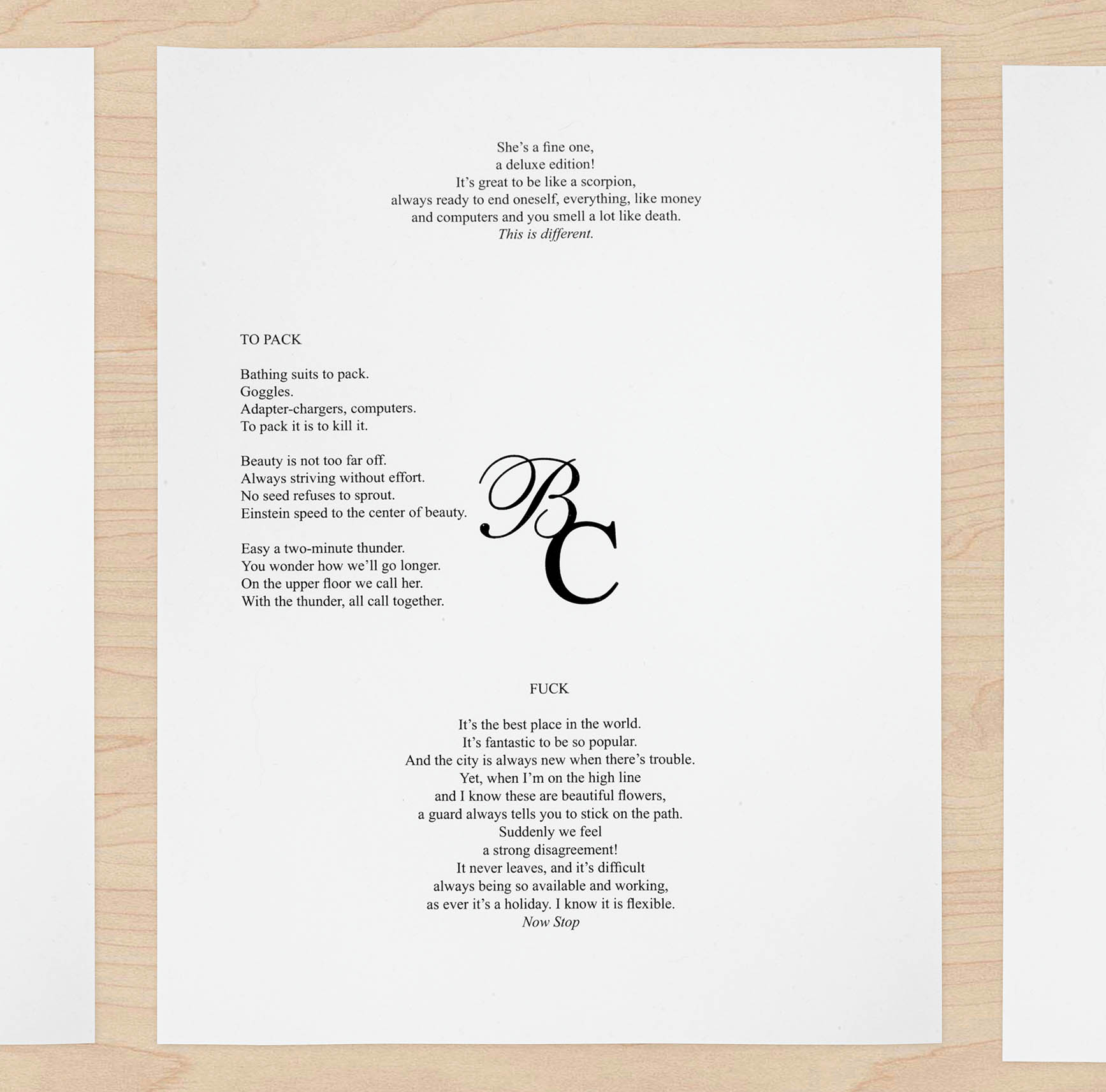

Bernadette Corporation, The Complete Poem, installation view, Greene Naftali, New York, 2009. Courtesy of the artists and Greene Naftali, New York. Photo: Jason Mandella.

The convergence of Steyerl’s and Rosler’s accounts with Rule and Levine’s is uncanny: recalling art criticism’s origins in ekphrasis, all four authors indirectly hail poetry as the only use of language that is capable of paralleling visual art. As Adorno famously wrote, “Artworks fall helplessly mute before the question ‘What’s it for?’ and before the reproach that they are actually pointless.”5 If the press release is meant to answer that question, both for the confidence of investors and the authority of art history, poetry deflects the question like a mirror, reflecting visual art’s insecurities back to itself.

On a scale of worthy to worthless, poetry stands at either pole; which is to say, poetry might demonstrate the way value is a circular concept. On the one hand, poetry is writing’s highest achievement, language exercised for its own sake, the literary corollary to Art with a capital “A.” On the other, poetry is an unpaid embarrassment, without purpose or social power. Perhaps it should come as no surprise that sublimated discussions of poetry occur when the relationship between visual art and value is at stake. A press release evidences art’s complex relationship to exchange. A press release is a form of advertising copy for commodity goods, soliciting capital investment. It is also a dividing line that separates art from other commercial merchandise, solidifying cultural capital. As copy, a press release can’t go on the product (that is, the artwork) itself. As culture, it can’t just name a price.

Steyerl and Rosler’s most worthy critique moves our analysis away from the particular linguistics of the press release and toward their authors: interns, gallery assistants, and other administrators, whose jingoistic failures index their low status in the art world, its unequal distribution of access to the trademarked jargon of higher education, and the assumed status of English as its lingua franca. As Chris Kraus points out in her gushing review of Bernadette Corporation’s 2009 exhibition The Complete Poem, a writer’s foremost role in the art world is to ascribe value to works of art; her own work is nearly valueless.6 While what’s written can result in financial returns for artists, the pay rate for writers is fixed in content-production’s current market valley. Writing produces value, but is devalued itself. In Kraus’s words, “It offers a badly paid livelihood.”7

Bernadette Corporation, The Complete Poem, installation view, Greene Naftali, New York, 2009. Courtesy of the artists and Greene Naftali, New York. Photo: Jason Mandella.

Bernadette Corporation’s The Complete Poem teased out this sticky antipathy between writing and art. For their 2009 exhibition, the collective paired A Billion and Change, what they call an “epic poem” (and what I call a stream of aphorisms for the salacious art-world citizen), with glossy, black-and-white photographs replicating a Levi’s ad campaign without graphic-designed brand overlay. A Billion and Change’s almost 200 pages were spread horizontally in vitrines throughout the gallery. The text moves through a series of formal conceits—a string of phrases around the initials “BC,” like “busy communicating…bustling to circulate…American balls are controlled,” a number of poems with around 14 lines, and individually titled lyrics—maintaining a self-important, New York-centric, first person narrator: “A search engine I am.”8 In the context of the exhibition, the photographed models could be the perfect denizens of that “I,” hanging above the vitrines in frames and the occasional fabric banner, sporting fashion-distressed denim, basic tops, or Bare Chests.

Chris Kraus celebrates The Complete Poem for its simple insistence on poetry as art. She quotes Bernadette Corporation’s John Kelsey, who disputes the assumption that “art should be for sale, writing should be for free.”9 But in her eagerness to praise the reversal as “radical” (her word)—and Bernadette Corporation’s albeit unmistakable “cool” (our word)—Kraus fails to offer any insight about how the distinct elements of the exhibition might function, or what they might actually do besides impress. Certainly, the later publishing of A Billion and Change as a book—priced at an above average but still reasonable $30, presumably because it includes the photographs as well—suggests the real gesture of The Complete Poem wasn’t the importation of poetry into art’s price range, but rather a comment on the relationship between art and writing, which functions just as well on the white walls of a gallery as in the white space of a page. What The Complete Poem actually provides is a picture of value as an ouroboros. Without a brand, the models’ anorexic dispassion advertises the poem itself, just as the poem is the purpose of their pouts. Poetry is as shallow as advertising copy; art is as bankrupt as an editorial spread.

What to make, then, of the recent rise of poetry as programming, poetry as art, and now, the use of actual poems as press releases? A biased, jaunting survey: In January 2013, when the first museum-sized galleries cropped up in warehouses on Los Angeles’ east side, they used poems as their press releases: Night Gallery and François Ghebaly inaugurated the trend with line breaks, “naughts,” and almost-nonsense.10 A year later, 89plus and the LUMA foundation published 1000 books of poetry by 1000 young poets to accompany Hans Ulrich Obrist’s exhibition Poetry Will Be Made By All! Meanwhile, Frieze Magazine dedicated an entire issue to “Artists’ Poetry,” including a contemporary poetry supplement.11 This year, young Los Angeles artists Marcel Alcalá and Nora Berman launched McPoems, inviting artists and poets and really whomever to read poetry at McDonald’s. The Guggenheim Museum opened Storylines, an exhibition supposedly structured around narrative but often simply around representations of books. In conjunction with the exhibition, the Guggenheim commissioned a response to each work by a contemporary poet, circulating the results in a collection of paperbacks marked “Do Not Remove.”

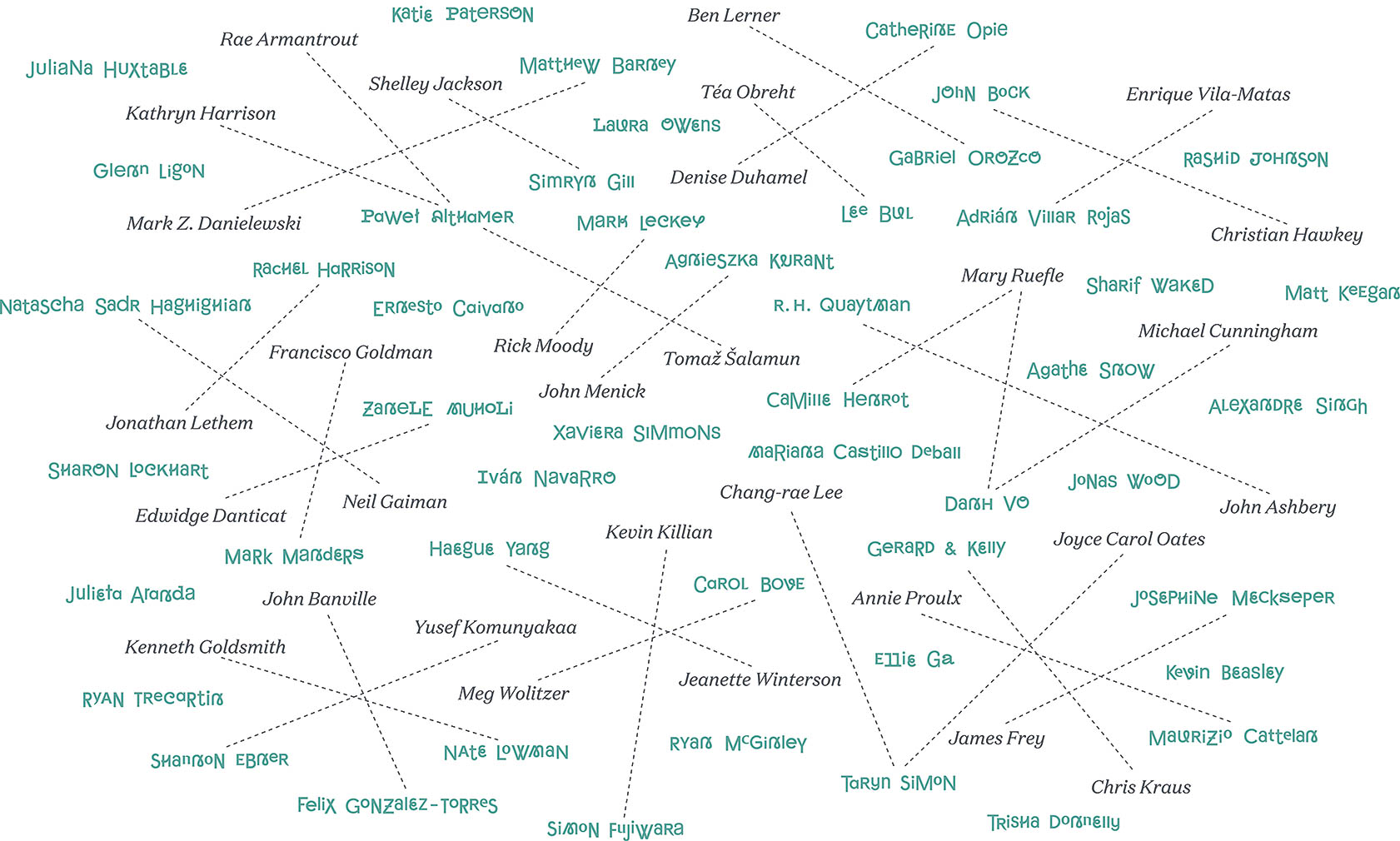

Map of participating artists and writers that appeared on the introductory wall of the exhibition Storylines: Contemporary Art at the Guggenheim, Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2015. Image: Janice Lee. Courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

As usual, we can congratulate the economy for drawing the disciplines together. Public divestment occasions close contact—in a collective huddle. More, in the climate of co-opted “creativity,” in which entrepreneurial labor of all kinds is promoted as passion, art, and craft at once, solidarity between poetry and art makes strategic sense. Of course, the Internet has played a vital role in shaping the alliance. “Perhaps,” Quinn Latimer writes in “Art Hearts Poetry,” her introduction to the artists’ poetry issue of Frieze, “art’s turn towards poetry…is about the new linguistic currency of the Internet: advertorial, adolescent, content-driven, anxiety-ridden, always appeasing, liking, performing, sharing, driving the shares up.”12 Poets may turn to artists for a share of their expanding social capital, but language has a privileged relationship to current forms of social media, and artists might look to poets to better ride the tide.

This materialist reading might best suit The Animated Reader, an anthology of contemporary poetry published by the New Museum in conjunction with the Surround Audience triennial. The triennial’s title hints at the exhibition’s messy simultaneity of artworks, offering the ideal perusing conditions for enthusiasts of object-oriented ontology: a landfill of stuff. Edited by Brian Droitcour (who has developed platforms for poetry at Rhizome and Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery and has described Surround Audience co-curator Ryan Trecartin as a poet), The Animated Reader similarly sprawls. Drawing from an international group of about seventy authors, The Reader braids tweets and blog posts with conceptual experiments and the occasional lyric poem, and single works with snippets of book-length projects. Many of its contributors are pedigreed poets with tenure or scores of awards, some are self-published trolls, some are artists from the triennial, and some I’ve never heard of and never care to again. The “animated reader,” Droitcour writes in his introduction, proposes an analog to the exhibition’s “animated viewer.”13 Well, I didn’t buy the spectator’s emancipation in the exhibition—even if the good work did eventually reward a dig, “surround” makes a too easy excuse for a frustrating curation of sound (an unruly substance that leaked across dividers) and scale (seemingly unconstrained except by each artist’s will to produce)—and I don’t buy a parallel “animated” construct for reading. It isn’t the rough that makes diamonds shine.

Is The Animated Reader where, as advertised, the exhibition’s broad-stroke stakes—technology, identity, and capitalism—find themselves worked out with words? Is the book just an extended press release? A written document that serves to add cultural value to the exhibition and monetary value to the artworks within? If the poets aren’t included as “participating artists,” if they receive no reviews, and, I imagine, little or no financial support for their contributions, do they make up the same underclass of art world adjuncts to which Steyerl offered poetry as a salve?

Cover of The Animated Reader, edited by Brian Droitcour, New Museum, New York, 2015. Courtesy New Museum, New York.

“Reader” is also what we call our literacy learning tools, collections of texts designed for students. In this context, I’d say Droitcour hit the mark: someone needs to teach the art world a lesson about poetry. With all of the triennial’s thematic breadth and none of the constraints on its contributors’ “emergent status,” The Animated Reader is rather 101 level. Accustomed readers of contemporary poetry will find familiar big names with an international focus and perhaps some frustration about why artists’ writing is thrown into their midst. But to an art world whose primary consumption of poetry is now limited to the A4 sheets of soon-to-be garbage separating them from a gallery assistant, any education is a good one. The point of a poetry class is to show just how much words can do. Yes, surveys are a slog, and The Animated Reader suffers for it. But at its best, The Animated Reader might be Steyerl’s Very Fucking English Lesson. Which is to say, it might do the exhibition better than the exhibition itself.

The Animated Reader’s most significant and successfully executed thread is an engagement with the English language: English as the language of colonial power and white supremacy, English as the prerequisite for academic and artistic success. The opening poem of the anthology, “Like in Valencia,” by the Mexican-born and New York City-acclaimed poet Mónica de la Torre, appears in Spanish, a bold gesture that displaces English from its assumed status as default and reorients English-speaking readers. The poem continues in a set of “equivalences”14 or translations that call into question the status of the original, spinning the idea of fidelity into a field of textual play. The injunction is plain: If language is poetry’s medium, English is always an artistic choice, even when we forget to consider it one.

The conflicts with English waged in the Reader demonstrate poetry’s often unique capacity to map identity onto language, and thus politics onto form. “English is / a foreign language / not a mother tongue,” M. NourbeSe Philip writes in her included “Discourse on the Logic of Language,” such a mainstay of Poetry 101 syllabi that I laughed to see it included. The poem is split into multiple registers of language, some operating simultaneously, printed in adjacent columns. In one, “language” transforms homophonically to “anguish.” In another, Philip prints two “edicts” that encouraged slave owners to split up ethno-linguistic groups and cut out the tongues of slaves who used their native language.15 As the bodily site of the production of speech, the tongue joins linguistic and racial identity; Philip performs the horror of this forced union. Similarly, in prominent Japanese poet Hiromi Ito’s included poem, “The Maltreatment of Meaning,” language acquisition becomes a metonym for colonial violence: “To learn a language,” she writes, “you must replace and repeat.” The poem ends:

You are happy meaning covered in blood is miserable

We are happy meaning covered in blood is miserable

The blood-covered meaning of that is blood-covered misery,

that is happiness.16

Like Philip, Ito twins language to racial and ethnic identity, using the tools of oppression against themselves.

Palestinian-American poet Fady Joudah’s “Or,” also in the collection, politicizes poetic expressions of subjectivity. Here is the poem in its entirety:

I’m abscess

A small state to subjugate the worldbody the word body or

I touch plurality so much I become the just-oneSelf-cell switch-cell

Communicative.17

It wouldn’t be difficult to substitute the “I” of this poem for poetry itself, the “abscess,” a “small” infected, afflicted growth. The sense of “subjugate” may echo the nationalist rhetoric of “state,” but also, syntactically, it might mean “to make subjects of,” just as “body” in the next line means both “embody” and “give shape to.” Those objectifying ripples make the homophone “sell” reverberate in “self-cell,” make “communicative” confessional. Each “I” that reads the poem inhabits its “I,” a “plurality” the poem “touches,” but also “subjugates.” The “body” is both a noun and a verb, something that happens to you as much as happens from you. “The just-one” is this sensual oxymoron of subjectivity, from within and without.18

Forms of communication inflect subjectivity, as both the relationship between language and identity and the relationship between language and technology prove. Cults of literary personality Bhanu Kapil and Kevin Killian make the Reader’s most significant contribution to the latter theme, trying on the weird and various skins of online communication with poignant daring. Kapil evokes historical memory and cultural trauma in the argot of diaristic blogs (“eat the blue right out of the eye”), updates (“Sentences / discharge their contents, as every animal must”), or participatory surveys (“Do you have a memory of a riot? …Please send your answer to: thisbhanu@yahoo.com”).19 Killian injects brutal lyricism into the form of an Amazon product review, and houses them on the Amazon website: “Tell me this ain’t the way push pins should be—like small, personalized power tools of the mind,” or, in “Serendipitous Adventure”:

Websters defines serendipity as “the aptitude for making desirable discoveries by accident,” and traces its origins back to the (fictional) isle of Serendip in the British fantasist Horace Walpole’s Gothic oeuvre.

Myself, I illustrate serendipity by remembering the day I stumbled across BUTTMEN3, a large collection of racy stories from divers [sic] hands all with a common theme…20

Alongside the Reader’s literary experiments with online communication are extant social media posts (blog excepts, Facebook status updates, and tweets), stamped with the time and date and distinguished by a sans-serif font. Most of the visual artists included in the Reader make their appearance solely through these posts. Droitcour chooses many by English artist Jesse Darling:

Jesse Darling. January 21, 2013 at 2:03pm

What? I’m fine! Jus [sic] practicing my Social Media Brand Strategy, like I even recuperate the collateral of my own emotions for social capital?21

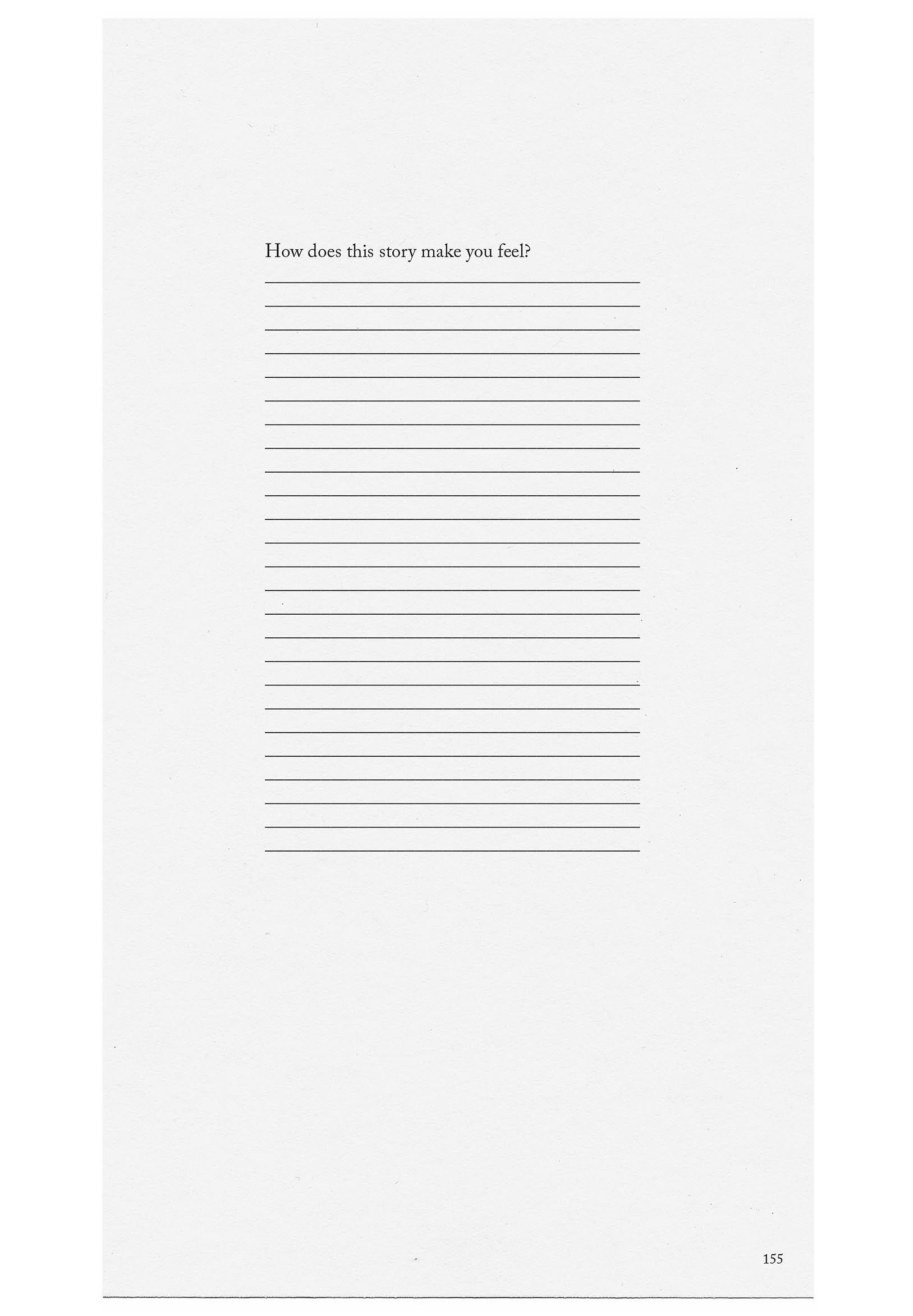

Darling reminds us that an artist’s social media persona, the amalgam of those “shares” of her emotional life, shapes her brand as an artist—maybe even as much as her work. Expressions of subjectivity online demand self-objectification. The specter of social media influences both the Reader’s shared content and its literary contributions, as authors chart a see-saw of self-promotion and deprecation. How to submit to social media’s star system of “rainbow conformity,” in poetry contributor Sawako Nakayasu’s elegant phrase?22 How to transform writing into an experiential commodity? In her included text, poet Divya Victor offers a gruesome narrative of a man cutting up a woman into twelve pieces, then poses the chilly, if unsubtle, invitation, “How does this story make you feel?”23

The Reader’s interest in social media can seem frivolous in the face of its sturdier themes. Worthy quips about day-to-day disappointments (“There’s a sign outside my womb that says, ‘Goodbye’” tweets Los Angeles animator and comic Casey Jane Ellison24) wither against Philip’s racial justice, just as the inclusion of giants like Philip (a Guggenheim fellow with no active Twitter account) tends to dwarf younger voices. Sometimes, the stature of a poet gets in the Reader’s way, as when a snippet chosen for the anthology fails to do justice to a whole must-read book. No one does conceptual synthetics like Harryrette Mullen (the one American member of the prestigious writing collective Oulipo), yet Droitcour’s choice of her alphabetical “Jinglejangle” proves an exemplary thud. The selections from Dodie Bellamy’s Cunt Norton and Brandon Brown’s The Poems of Gaius Valerius Catullus similarly depreciate. These books work their magic through accretion; their wholes add up to more than their parts. As usual, the generic anthology critique should go without saying: there are essential works by contemporary poets whose absence offends my sensibilities, though who has time for a list?

Divya Victor, excerpt from “Answer,” in Things To Do With Your Mouth, Les Figues Press, Los Angeles, 2015. Reproduced in The Animated Reader, edited by Brian Droitcour, New Museum, New York, 2015. Courtesy the author and New Museum, New York.

“Love is a lossy format,” goes an included Jesse Darling tweet.25 Sometimes, The Reader proves a lossy test for the chops of the triennial artists it features. Ed Adkins is a decent artist, but without the hypnotic, maximalist binding agent of his signature videos, his words curdle on the page. Claims for his invention of a “high-definition” language might be a perfect exemplar of the poetic license of the International Art English press release. Juliana Huxtable’s writing, however, belongs with Kapil’s and Killian’s. Calling for queer techno utopias in all caps—“SHOUT OUT TO MY URBAN ANGELS SEARCHING FOR POST-OR-PRE-GENITAL DESIRE VIA GPS”—Huxtable inhabits language and, crucially, the platforms that now house it, with analytical acuity and sensuous appeal.26 Like the Levi’s ad that inspired Bernadette Corporation’s photographs, “cool” seems to be the sole organizing principle of Huxtable’s sci-fi posters, included in the triennial (and incidentally, in the Guggenheim’s Storylines), but as a delivery method for her racy diagnostics, I’ll take what I can get.

While Huxtable’s poetic productions are often formed in the process of a share, Atkins notoriously refuses to make his videos accessible outside of the gallery context, despite myriad HD possibilities. Surely, the lossy format of reproduction reveals a key philosophical difference between poetry and visual art. When an artwork is reproduced (in the context of this essay, for example), the image is considered documentation of the work; when a poem (like Fady Joudah’s “Or,” printed above) is reproduced, it is still the work itself. No matter the resolution of a .TIF, poetry travels better than visual art.27 Which is to say, wherever it travels, it gets to be itself. Poetry’s easy piratability is a paradox of powerlessness and power.

Installation view of Surround Audience, with works by Ed Adkins, Juliana Huxtable, and Frank Benson, New Museum, New York, 2015. Courtesy New Museum, New York. Photo: Benoit Pailley.

Roman Jakobson, one of Russian formalism’s central antecedents, once described poetry as “organized violence committed on ordinary speech.”28 In the Reader, contemporary Russian poet Roman Osminkin (whom The Reader introduced me to), appropriates Jakobson to reductio ad absurdum. In an included status update, Osminkin writes:

poetry is organized violence against language

language is organized violence against society

society is organized violence against nature

…

life is organized violence against time

time is organized violence against space.29

If Juliana Huxtable’s imperative strings epitomize The Reader’s twin themes (language and identity as well as language and communication technology), Osminkin claims its existential pulse, haunted by poetry’s purpose. Jakobson’s formalist maxim is often read as an oxymoron: what can poetry actually do? One of Osminkin’s included poems, “Poems and Fuckery,” takes this as its subject. It begins, “you know how sometimes you’re writing a poem / and at the same time children in india [sic] are starving,” as comic and cavalier as its title. What can poetry actually do? (About global poverty? Nothing.) But perhaps, as Sianne Ngai concludes in her essay “The Cuteness of the Avant-Garde,” poetry’s attempts to deal with its own limitations deliver more than masochism.30 Ngai offers, “indices of [poetry’s] powerlessness in commodity society [can be] reconfigured as indices of its distinctive ability to theorize powerlessness in general.”31 That is, the medium’s lack of social agency strengthens its capacity for social diagnosis.32 Osminkin’s “Poems and Fuckery” closes with the appeal, “so hurry up and write / …and finish your poem already / maybe / you / can still / save someone.”33 Whether it’s the poem that will do the saving, or the poet, now freed from the pen or the keyboard, is left appropriately ambiguous.

Installation view of Surround Audience, with works by Juliana Huxtable and Frank Benson, New Museum, New York, 2015. Courtesy New Museum, New York. Photo: Benoit Pailley.

A presumption of the use of poetry as press releases for exhibitions of contemporary art is that poetry needs no justification, no press release of its own to explain its value. “Perhaps artists are tired of use value,” Quinn Latimer offers in “Art Hearts Poetry.” “Perhaps poetry…seems like a strange, unknowable, useless (in the best sense) place of respite.”34 Through Siane Ngai’s paradoxical inversion of poetry’s powerlessness as its strength, I might offer the utter reverse. Perhaps visual artists are tired of their own uselessness; perhaps poetry seems like a strange, immediate, handy field of action: more easily disseminated through contemporary channels, more honestly reckoned with its limitations as a form. The fantasy of poetry as a refuge, the impression that poetry circumvents the demands of art, is condescending at best, and facile deception at worst. Like most exoticism, art’s crush on poetry is founded on a fascination, not with an escape from but rather a return to the real.

Roman Osminkin. October 10, 2013 at 4:46 p.m.

Dmitry Vodennikov writes about a dachshund that peed while he was

holding it and his post gets 166 likes

You write about how you have doubts about the meaning of life and

your post gets likes from a handful of fellow doubters

Conclusion: one must write about dachshund pee in such a way that

makes everyone have doubts about the meaning of life.35

Installation view of Surround Audience, with work by Steve Roggenbuck, New Museum, New York, 2015. Courtesy New Museum, New York. Photo: Benoit Pailley.

“I feel like I’m touching the sublime hugeness of the world,” Steve Roggenbuck says in a recent video, while fondling a cement column.36 Osminkin’s conclusion that “one must write about dachshund pee in such a way that makes everyone have doubts about the meaning of life” could be a working methodology for Roggenbuck’s practice. A writer who self-publishes all of his books,37 couch-surfs across the country to read them, and shares his language-happy videos for free on YouTube, Roggenbuck makes a lovely exemplary figure; in Surround Audience, a few of his videos were tucked rather capriciously next to the toilets. In one, Roggenbuck wanders around an apartment wearing a cheetah spirit hood, matted with age and sweat, over a soundtrack that blends EDM with advertising’s manipulative strings and, in rapid cuts, screams “I love hugging people…I want cake…I like dancing…I like kissing you!” Roggenbuck makes a much-needed mockery of the poetic epiphany, while actually managing to inspire. He smears a “dachshund pee” populism into pleas for empathy and care. Rather than Bernadette Corporation’s morbid dichotomy of writing and art, Roggenbuck advances a mash up, crass as it is catchy. “We have YOLO,” Roggenbuck reminds us. “Make something beautiful before you are dead.”38 In the context of the triennial’s basement, it might be easy to pity Roggenbuck’s absurd sincerity, to imagine Roggenbuck, a poet in a contemporary art exhibition, as a new Keith Arnatt, holding Arnatt’s cheeky, all-caps avowal, “I’M A REAL ARTIST,” with a pleading smile—for as Arnatt knew, a positive claim just insinuates its opposite.39 Instead, for a better sign of our times, I’d give him: “HAVE POEMS—WILL TRAVEL.”

Tracy Jeanne Rosenthal is the author of three chapbooks, Ri Ri (Re)Vision (Publication Studio), This Is The ENDD (Wilner Books), and Close (Sibling Rivalry Press). Her criticism appears regularly in Art in America and Rhizome. More at TJR.XXX or @XXEXEGESIS.