Perhaps the first thing to recognize is the narrowness of contemporary ambitions for knowledge to be acquired from the museum: what do we really learn from museums anymore?

—Bruce Robertson1

Museums have become predictable affairs. Too often, discipline-specific categories restrict the knowledge we gain from objects and didactics dictate how we should think about a particular work. In contrast, the Museum of Jurassic Technology’s (MJT) rich and varied exhibits allow viewers to lose themselves in a multitude of different worlds where familiar taxonomies and museological conventions no longer apply.2 The museum’s new wing, titled Fauna of Mirrors: A Catadioptric Bestiary, exemplifies this ethos. A mesmeric two-tiered structure, the Bestiary plunges viewers into a medieval universe of illuminated manuscripts and animal worlds. In addition to these transporting qualities, the Bestiary continues the museum’s ongoing exploration of pre-Enlightenment epistemologies and practices deemed obsolete or irrelevant as a means to reevaluate their significance for the present.

This interdisciplinary and transhistorical approach is apparent in the museum’s fascination for Renaissance wunderkammern, as expressed in the wing dedicated to the experimental scholar and curator Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680). Kircher presided over the College of Rome (1651–80), one of the most sig- nificant cabinets of the time. It is also evident in the museum’s “ethnographic and zoological holdings,” which include the Horn of Mary Davis Saughall (an animal-like horn believed to have protruded from the back of Saughall’s head), a miniature fruit-stone carving of a Crucifixion scene, and a hawk’s hood modelled on Henry VIII’s hawking ephemera, which has made its way into the Bestiary.3

Although bestiaries declined in popularity as wunderkammern emerged, both deployed wonder and storytelling as tools for knowledge production. In bestiaries, this manifested in the tales dedicated to animals’ superhuman and other-worldly powers and in wunderkammern in the playful juxtapositions and constellations of objects from diverse eras and practices that conjured an abundance of narratives. In both cases, readers (or viewers) were encouraged to engage their own imaginative capacities when deciphering a text or object and, in doing so, create new associations and meanings for themselves. This generative approach to interpretation and respect for viewer agency is palpable in all aspects of the MJT, where curiosity and wonder drive the acquisition of knowledge and the museum is reimagined as a site for extraordinary experiences. The Bestiary is the latest embodiment of this idea, where vistas into forgotten histories, beliefs, and practices that have since been erased or dismissed as inconsequential are encountered and reconsidered with renewed vigor.

I.

Unlike the MJT’s immersive, three-dimensional version, which envelops the viewer in a panoramic scene of real and mythological creatures, bestiaries traditionally manifested as illuminated manuscripts comprising narratives devoted to the fantastical exploits of non-human animals. Rendered in allegorical form, these tales were used to elucidate scripture, impart zoological knowledge, and model good behavior. While the majority of bestiaries were produced during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, they derived their content, form, and structure from the Physiologus, a codex compiled in the second century CE, in Alexandria, Greece. Although the Physiologus made extensive use of Classical scholarship on the natural world, it did so in order to manipulate that knowledge for religious purposes so that it might, as art historian Debra Hassig observes, “serve a new, didactic purpose, which resulted in the Christianization of Classical information.”4 Consequently, narratives were read through an evangelical lens that characterized animals’ behavior (and sometimes their appearance) as synonymous with good or evil. This remained the model until the Etymologiae of Isidore of Seville emerged in the seventh century, which was considered to be the second most influential of the genre. More secular in its focus, the Etymologiae sought to understand the nature of animals by examining the history and origins of their names in relation to their physiology, environment, and habits. This new approach provided an alternative to the Physiologus’ proselytizing function and reasserted the significance of Classical scholarship on bestiaries. Subsequent bestiaries compiled between the ninth and the fourteenth centuries varied stylistically in terms of their visual imagery, textual contributions, and ideological focus, but they all reflected the form and content of the Physiologus and Etymologiae, which were used as primary sources.

Fauna of Mirrors: A Catadioptric Bestiary, installation view, Museum of Jurassic Technology. Courtesy of the Museum of Jurassic Technology. Photo: Brica Wilcox.

From our current perspective, the fantastical nature of bestiary allegories might seem naive or simplistic, however, their narrative style was in keeping with other forms of medieval literature, such as the Ancient literary tradition of paradoxography and travel writing, both of which delighted in florid accounts of the bizarre, alien, and incomprehensible.5 While paradoxography took the form of descriptive catalog entries, travel literature frequently merged fact with speculative fiction to create extraordinary tales. These included imaginary lands populated by gigantic ants, two-headed serpents, barnacle geese that spontaneously generated from trees, and Scythian lambs—animal-plant hybrids connected to the ground with a robust stalk. History of science scholars Lorraine Daston and Katherine Park note that these forms of literature—like bestiaries—were less concerned with strict definitions of truth and instead “offered pleasure and entertainment. They enlarged their readers’ sense of possibility, allowing them to fantasize about alternative worlds of barely imaginable wealth, flexible gender roles, fabulous strangeness and beauty . . . [T]hey demanded emotional and intellectual consent rather than a dogmatic commitment to belief.”6

This expansive and imaginative approach to meaning and interpretation abounds throughout the MJT and resonates in the elaborate and convoluted narratives accompanying works such as Delani/Sonnabend Halls and Stink Ant of the Cameroon. In the former, a scientist examining the neurological pathways of carp has a major breakthrough in his research after attending a performance by an opera singer suffering from Korsakoff’s syndrome.7

Ceiling mural by José Clemente Orozco Farías. Installation view, Fauna of Mirrors: A Catadioptric Bestiary, Museum of Jurassic Technology. Courtesy of the Museum of Jurassic Technology. Photos: Brica Wilcox.

Ceiling mural by José Clemente Orozco Farías. Installation view, Fauna of Mirrors: A Catadioptric Bestiary, Museum of Jurassic Technology. Courtesy of the Museum of Jurassic Technology. Photos: Brica Wilcox.

In the latter, an old-fashioned audio device recounts the history of a particular species of ant driven to suicide by spores lodged in its head. In both cases, the narratives are utterly engaging, but their veracity is questionable. This aspect of the MJT has been explored in depth in Lawrence Weschler’s Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonder (1996), in which the author goes to considerable lengths to trace each history and sift the facts from the fiction. Weschler’s obsession with validating the authenticity or provenance of an object is at odds with the spirit of the MJT, where the exhibits’ factual nature is secondary to the intellectual and imaginative possibilities they provoke. In this way, the MJT’s exhibits function in a manner similar to medieval paradoxography and travel literature, which allowed readers to insert themselves into the meaning of the text and by doing so engage their own interpretive and imaginative faculties.8

While the exploits of non-human animals and their hybridized forms were embedded in the medieval imaginary and formed part of the lexicon of wonder, they also served a moralistic purpose, for example, to warn against bestiality and other unorthodox sexual practices. The most pernicious use of animal narratives was to demonize specific groups in European society, such as the Jews and the Irish. Such racializing of animal behavior is a constant theme in certain medieval bestiaries. One frequently finds the personification of Jews reflected in the textual and visual characterizations of hyenas, barnacle geese, night crows, and panthers. It is also present in travel literature, for example, in the anti-Semitic diatribes of Mandeville’s Travels (circa 1357–71)9 and in the anti-Irish commentary of Gerald of Wales’ Topographia Hibernie (1185), in which, as Daston and Park remark, he describes the Irish as “barbarians, ‘adulterous, incestuous, unlawfully conceived and born, outside the law, and shamefully abusing nature herself in spiteful and horrible practices.’”10 By equating Jews with animals or the Irish with aberrant sexual practices, it became not only possible but morally justifiable to mistreat them. Such skewed logic has been used for centuries to rationalize atrocities.

II.

The MJT does not foreground such negative associations. Instead, the museum has built a church-like structure that honors animals and casts humans as interlopers. This new wing is titled in reference to Jorge Luis Borges’s story “Fauna of Mirrors,” from The Book of Imaginary Beings. Borges’s story relates two parallel worlds during the reign of the Yellow Emperor. One realm was populated by humans and the other by fantastical creatures who used mirrors as portals to travel back and forth. After a failed coup on the part of the animals, the Emperor “imprisoned them in their mirrors, and forced on them the task of repeating, as though in a kind of a dream, the actions of men. He stripped them of their power and reduced them to mere slavish reflections.”11 While this can be read as an allegory for the violent civilizing rituals of colonial oppression, it can also be interpreted from the perspective of humans mistreating animals in zoos, farms, circuses, fair grounds, and animal parks, or as pets in their homes—all forms of ideological violence against animals. Just as the readers of Borges’s story are expected to side with the fantastical creatures, who prevail over their human captors, so too are the visitors to the MJT’s Bestiary, who enter a parallel world ruled by, and for, animals.

Embedded in the alternative thinking processes conjured by Borges is a critique of how knowledge is conventionally structured and disseminated. The writer conveys this best in a passage dedicated to “a certain Chinese encyclopedia,” in his essay “The Analytical Language of John Wilkins.” Here animals are organized according to an alternative taxonomic system that describes them as: “(i) frenzied, (j) innumerable, (k) drawn with a very fine camelhair brush, (l) et cetera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher.”12 As Michel Foucault remarks of this text, “In the wonderment of this taxonomy, the thing that we apprehend, in one great leap, the thing, that, by means of a fable, is demonstrated as the exotic charm of another system of thought, is the limitation of our own.”13 Analogously, the MJT is invested in rethinking familiar mechanisms and formats of conventional museology, reimaging what a museum can be. In the Bestiary, this radical revisionist project emphasizes the elevated role that animals played in the production and acquisition of theological, social, and cultural knowledge in the medieval era in the interest of recovering the bestiary’s intellectual function and its possible relevance for today.

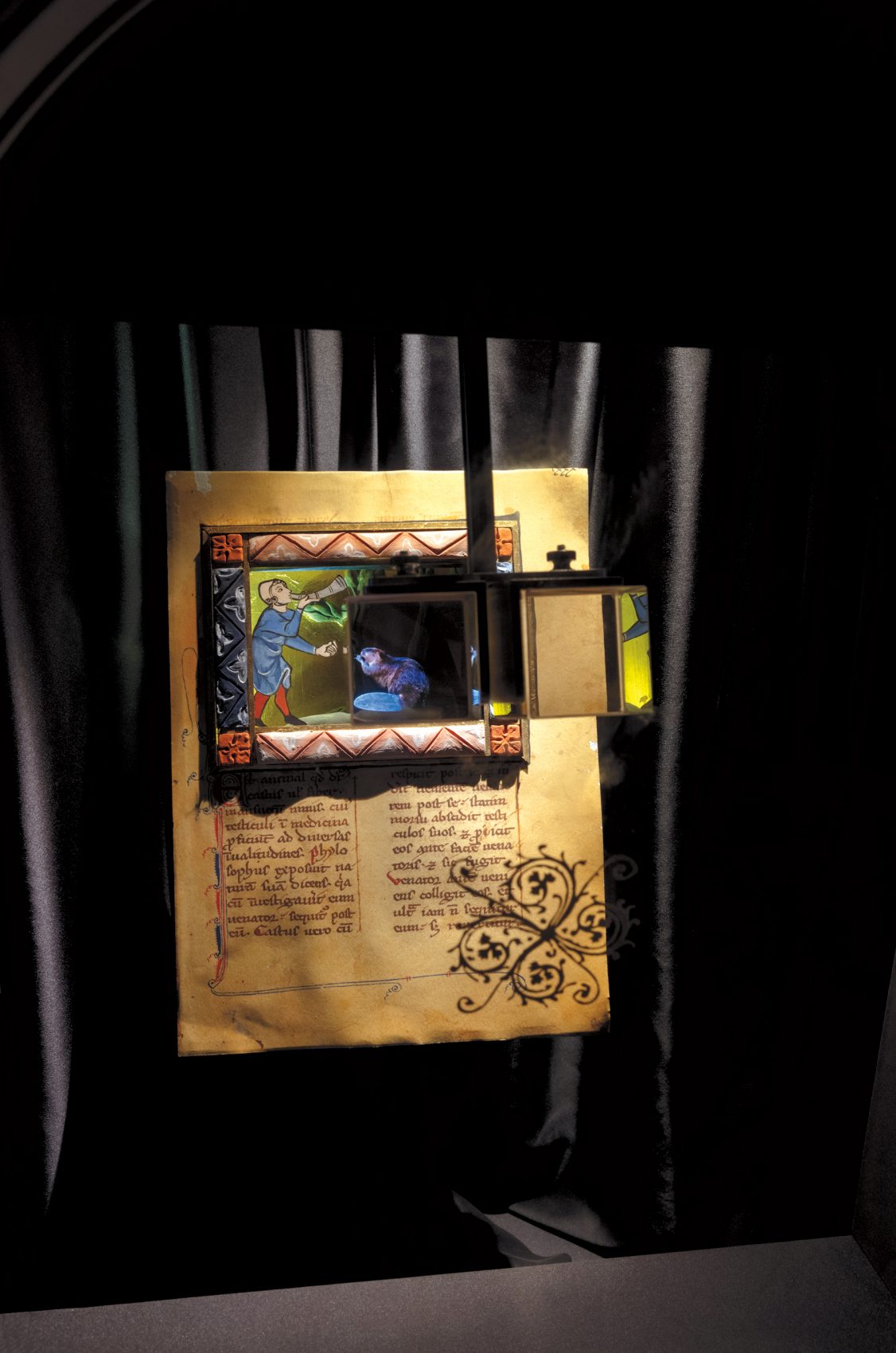

Located at the back of the museum, the two-story animal kingdom is reached via a dark narrow passageway framed by exhibitions from Failing Dice from the Collection of Ricky Jay. Upon entering, one path leads up and another down.14 Ascending a spiral staircase leads to a Gothic-style tower topped by a dome embellished with real and fictional creatures—including a lion, pelican, crane, ouroboros, phoenix, and seraphim—painted by artist José Clemente Orozco Farías. Reversing the familiar human/non-human animal hierarchy, viewers are subjected to the panoptic gaze of the creatures encircling the viewing platform. This exposed and surveilled area contrasts dramatically with the space below, which can be accessed at the bottom of the stairwell. Comprising small alcoves housing discrete shadowboxes and dioramas, these works allow for intimate, individual encounters with animal worlds. While the contents vary, a number of the exhibits include fabricated pages from illuminated manuscripts, which are assigned to different animals. In keeping with their post-seventh-century versions, the text is written in Latin, leaving those unfamiliar with the ancient tongue to rely on the scenes painted in shallow bas-reliefs on the surface of the page. When one looks at the pages through the lens of a stereoscopic prismatic viewing device, moving images of animals are projected onto the painted scene. Beneath the displays are didactics in the form of allegorical tales that have been appropriated from a range of medieval bestiaries—Physiologus, Etymologiae, Book of Beasts, Ashmole, and Aberdeen.

Among the animals represented is the beaver, which is represented with a miniature looped animation viewed through the stereoscope. Inserted into a bas-relief forest scene alongside a huntsman with a horn, the beaver circles and stands on its hind legs. The accompanying didactic tells the familiar bestiary fable in which a beaver bites off its testicles and throws them at the hunter in order to put an end to the chase. If pursued again, the beaver stands on his legs to expose its castrated state and is left alone. Within religious contexts, the beaver’s act of self-mutilation was understood to represent the cloistered existence of monks and friars, who had dedicated their lives to abstinence and prayer. It served a similar function outside the monastery, to encourage people to live a chaste and virtuous existence. While most of the illustrated manuscripts of the time depicted similar scenes, a few added their own embellishments, such as the Ashmole, which not only enlarged the beaver’s genitals but also rendered them in a bright orange hue to emphasize the corrupting influence of sexual congress.15

While the MJT’s beaver narrative remains true to its historical bestiary referents, the religious and sexual moralizing is absent. Instead, the beaver’s exploits can be read as a defensive act against the violence of the hunt and by extension gratuitous human cruelty toward animals. As anthropologist Matt Cartmill observes, historical views on hunting have changed dramatically over time. For the Ancient Greeks, hunting had immense symbolic value. Some Romans regarded it as “a farm chore with no more symbolic or mythical importance than catching rats,”16 and other Romans considered it barbaric. In medieval Europe, hunting was reserved for the aristocracy, who coopted for their own private playgrounds large areas of land previously occupied by peasants. Viewed from this perspective, the MJT’s beaver could be understood as a symbol of class rebellion and its testicles weapons for waging war—and symbolic of their absolute dedication to the struggle—against exploitative feudal landlords.

The hyena is also celebrated in the MJT’s menagerie. In traditional bestiaries, the hyena was characterized as a duplicitous creature capable of mimicking the sound of human vomiting and cadence of voice, in order to lure human victims to their deaths. They were frequently portrayed ransacking tombs and feeding on human corpses—which are always pictured whole, in keeping with medieval fears around decomposition and resurrection of the flesh.17 In addition to these unconventional habits, the hyena was cast as sexually ambiguous—shifting between the male and female sex each year. This trait was used by the Church and State to underscore their punitive views on non-conforming sexual practices and identities, which were subject to severe, sometimes capital, punishment. To emphasize this aspect, the hyena was often depicted as a hermaphrodite, with both sets of genitals in place, often exaggerated to emphasize its perceived aberrant sexual nature and compromised character. If these projected flaws were not enough, the hyena, as previously mentioned, was also used to promote anti-Semitism, which was rife in Europe during this period.

Beaver (Castor, Bievre, Fiber) display. Installation view, Fauna of Mirrors: A Catadioptric Bestiary, Museum of Jurassic Technology. Courtesy of the Museum of Jurassic Technology. Photo: Brica Wilcox.

Although the hyena’s fluid sexuality, impressive impersonation skills, and macabre feeding habits are included in the MJT’s descriptive text, it does not situate these characteristics within an historical, theological, or moralizing context. As a result, the hyena’s behavior no longer functions as a figuration for xenophobic or sexist sentiments, but instead can be interpreted in different ways. These include the possession of other-worldly and wondrous powers, which enables the hyena to immobilize creatures with its variegated gaze. It also conceals a stone behind its eye that, when removed and placed beneath a human’s tongue, allows them to see into the future. These magical aspects connect the hyena to a time in the past when animals, as art historian John Berger has written, “first entered the imagination as messengers and promises,”18 not only as potential food or clothing. As Berger discusses, the marginalization of animals corresponded with the rise of industrialization, where animals once revered for their multi-dimensional qualities were now “treated as raw material . . . and processed like manufactured commodities.”19 The Bestiary recuperates these lost associations. Rendered as projected apparitions—as the museum refers to them—they function as ghosts reasserting their former role as mediators between the physical and invisible realms.

Fauna of Mirrors: A Catadioptric Bestiary, installation view, Museum of Jurassic Technology. Courtesy of the Museum of Jurassic Technology. Photo: Brica Wilcox.

Held in high regard at the MJT, dogs also have a strong presence in the Bestiary, as represented by its coat of arms, which features a dog-headed winged creature based on the MJT’s rescue dog, Lisitsa. Another of the museum’s dogs, Neba, is used as a model for an animation of three whippets projected onto a diorama dedicated to bestiary dogs. Adjacent to this is a text panel dedicated to Saint Guinefort, a thirteenth-century French greyhound posthumously canonized for saving a child from being killed by a snake. On the lower floor of the Bestiary, a small portrait depicts a dog-headed human in clerical garb. Beneath the painting, a few blades of grass fill a delicate glass vase—perhaps an altar for the Bestiary’s cynocephalic saint. This dog-human hybrid is modeled on a seventeenth-century icon by an anonymous painter that appears as a black-and-white image in the museum’s exhibition Special Cases: Natural Anomalies and Historical Monsters, curated by artist Rosamond Purcell. Accompanied there by a wall text,20 the dog-headed saint is displayed next to an image of a crane-necked man and a “Mermaid giving birth to twins while kissing her consort.”21 Here, as in the Bestiary, the image of the dog-human is a testament to the medieval fascination with wonder and the “insatiable human appetite for the rare, novel, and the strange.”22 Far from gratuitous, these anomalies functioned as ciphers for reflecting on and decoding the complexities of the world and were later included in wunderkammern, where they held a similar role.

Hyena (Hiena, Hienne, Hyene, Iena, Luvecerviere, Yena, Yenne) display. Installation view, Fauna of Mirrors: A Catadioptric Bestiary, Museum of Jurassic Technology. Courtesy of the Museum of Jurassic Technology. Photo: Brica Wilcox.

III.

In terms of its celebration of non-human forms of intelligence, the Bestiary finds its symbolic twin in the earlier work Tell the Bees: Belief, Knowledge and Hypersymbolic Cognition (1994–95). Comprising a series of dioramas containing animal-related artifacts, the displays in this wing are accompanied by descriptive texts presented in the same format as those in the Bestiary that highlight the curative and protective properties of the animals referenced. Exhibits include a wax human head sucking the breath from a duck’s beak, believed to cure throat infections; a pair of hands covered in dog hairs, used to heal an open wound; a gilded kingfisher egg believed to have a calming effect on stormy seas during egg-laying season; and an image of a flock of sheep thought to improve respiratory ailments. Although these ideas have since been discredited as folklore or superstition, the use of zootherapy from the Classical era to the eighteenth century was not only widespread but validated by nascent scientific authorities.

By highlighting the diverse and significant roles that animals once played in human lives, Tell the Bees and the Bestiary underscore our current estranged relationships with non-human animals. These exhibits remind us of what we have lost by referencing a time when animals and their bodies were revered for their superhuman, shape-shifting, or apotropaic properties. In the Bestiary, these ideas are embodied in the creatures believed to spontaneously generate (bees from rotting carcasses or salamanders born of fire); in those with the ability to resurrect their young (pelicans and lions); and in the figure of the phoenix, who was capable of cheating death by rising from the flames as a worm to be born again. The curative potential of animals is represented by the gilded ostrich and griffin eggs displayed in shadowboxes on the lower floor, which were traditionally thought to ward off evil. The unicorn (its horn later understood to belong to a narwhal) painted on the Bestiary ceiling has a similar function: its horn was crushed and made into a potion used as an antidote to poison.

In addition to the Bestiary and Tell the Bees’ formal similarities and shared focus on the preternatural qualities of animals, both have descriptive panels written in a narrative style that links them to fables and fairytales, where animals rule and the fantastical is as valid as the commonplace. Just like Borges’s “Fauna of Mirrors,” the mini fictions that constitute the MJT’s didactics transport viewers to other realms. These texts are distinctly different from the information-driven didactics typically used in museums. In this way they resonate with Walter Benjamin’s celebration of storytelling and his lament over its decline. Storytelling, he argued, had been replaced with information, an inferior form of communication that lacked texture, depth, and experience: “No event any longer comes to us without being shot through with explanation. In other words, by now almost nothing that happens benefits storytelling; almost everything benefits information. Actually, it is half the art of storytelling to keep a story free from explanation as one reproduces it.”23 In contrast, storytelling as deployed in the MJT’s didactics encourages viewers to make sense of the work on their own terms by bringing their own subjective experiences to bear on the interpretation of the work rather than being force-fed facts.

Cynocephaly (Dog-Headed Saint) Icon, circa 2015-18. Installation view, Fauna of Mirrors: A Catadioptric Bestiary, Museum of Jurassic Technology. Courtesy of the Museum of Jurassic Technology. Photo: Brica Wilcox.

While many of the MJT’s descriptive texts can be traced to historical or museological references, an equal number have been altered to confuse their sources. This is evident in the Bestiary text panel for Saint Guinefort, which conflates a thirteenth-century French fable with the fourteenth-century Italian myth of Saint Roch.24 While both involve dogs as saviors, they are situated in different historical periods and geographical regions, suggesting that it is the essence of the story that matters, rather than its historical accuracy. Other didactics that have been subtlety altered include Rosamond Purcell’s textual description for Special Cases: Natural Anomalies and Historical Monsters, which is accompanied by the following quote, “Ancient traditions when tested by the severe processes of modern investigation commonly enough fade away into mere dreams; but it is singular how often the dream turns out to have been a half-waking one, presaging a reality.” Purcell attributes this quotation to T. H. Huxley’s Book of Beasts—which is in fact a twelfth-century bestiary translated by T. H. White. But the quote was actually appropriated from the first page of T. H. Huxley’s Natural History of Man-Like Apes, one of the first books written on human evolution in 1863. By intentionally confusing authors and book titles, the text framing the work is given an entirely different meaning. While this quote is appropriated from a nineteenth century book, Purcell’s curated wing of Special Cases: Natural Anomalies and Historical Monsters suggests that there is much to be gained from revisiting pre-Enlightenment views on anomalies, which celebrated the bizarre and unfamiliar as portals for new forms of knowledge production rather than opportunities for discrimination.

IV.

The MJT’s altering of sources and references throughout its exhibits calls attention to the ways in which museums deploy display technologies to produce knowledge. As scholar and curator Bruce W. Ferguson has remarked, “The system of an exhibition organizes its representations to best utilize everything, from its architecture which is always political, to its wall coverings which are always psychologically meaningful, to its labels, which are always didactic (even or especially in their silences), to its artistic exclusions, which are always powerfully ideological and structural in their limited admissions, to its lighting, which is always dramatic.”25 The MJT renders these museological mechanisms visible by juxtaposing unorthodox content with conventional systems of display. Once attuned to the subterfuge, one becomes suspicious of the authority embedded in these systems of display. Similarly, the dioramas and vitrines throughout the MJT, although alluding to the traditional language of museums, deliberately fail to adequately validate the exhibits contained within. Instead, the uncertainty engendered by these works and their mode of display challenges viewers to question what they are actually seeing and reading.

Ceiling mural (detail) by José Clemente Orozco Farías. Installation view, Fauna of Mirrors: A Catadioptric Bestiary, Museum of Jurassic Technology. Courtesy of the Museum of Jurassic Technology. Photo: Brica Wilcox.

In addition to drawing attention to the presentation of its subjects, the MJT’s critique of museological practices also takes place at the level of content. By refusing to limit its focus to just one field—be it art, natural history, science, alternative belief systems, or craft—the MJT encourages viewers to question the rigidity of discipline-specific identities, knowledge hierarchies, and taxonomic systems deployed by conventional museums to generate and configure meaning. Central to the MJT’s overarching project is the exploration and rehabilitation of antiquated cultural forms as means to expand the intellectual and historical parameters of contemporary museums, which the manifestation of the Bestiary goes some way to achieve. The scholarly and cultural significance of bestiaries have largely been ignored in historical accounts.26 They have traditionally been dismissed as intellectually bereft—a category of medieval literature that used simplistic animal narratives as teaching devices for the poor. However, as cultural theorist Sarah Kay has written, they were “sufficiently varied to include twelfth-century literati, thirteenth-century arts students, scholars of natural science, and theologians of all kind,” suggesting that they had a far greater impact on medieval culture than is presently understood.27 MJT’s three-dimensional installation embodies this multi-dimensional aspect of bestiaries. Buttressed by expansive lyrical texts that allow for multiple access points and interpretations, the Bestiary encourages a reconsideration of the genre’s former significance as well as its potential value in the present for reconsidering attitudes towards storytelling, polysemy, and non-human forms of intelligence.

Ciara Ennis is the director and curator of Pitzer College Art Galleries. Her current research explores the appropriation of Wunderkammer tactics in contemporary curatorial practice. Ennis is a member of X-TRA’s Advisory Council.