Collective memory is without a doubt more the sum of what has been forgotten than the sum of memories.

-Joel Candau1

Video art imitates nature, not in its appearance or mass, but in its intimate ‘time-structure,’ … which is the process of AGING (a certain kind of irreversibility).

-John Hanhardt2

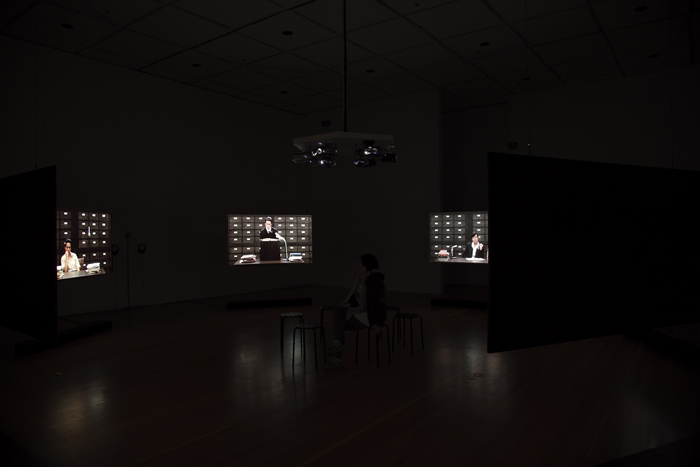

Criminal Case 40/61: Reverb, a multimedia installation created by Andrea Geyer and staged at the University Art Gallery at the University of California, Irvine, is coolly compelling and thought-kindling in its austere, yet well-tuned display of photographed artifacts (both genuine and facsimile), audio recordings, and video performances reenacting the 1961 trial of Holocaust administrator and SS Lieutenant-Colonel Adolf Eichmann by the Israeli Supreme Court. Divided into three interlocking spaces of observation, and running the technological gamut from analog to digital, the installation provides a model for alternative public pedagogy while marking a salutary turn in installation choreography and especially, audiovisual representations of the Jewish Holocaust and its aftermath. Cryptic in its signage upon first perusal, cannily dispassionate in its rendering of the proceedings, and indiscriminate in its revolving mode of address, the effects of this work on most viewers will likely be delayed, boosting its profile as a processual rather than spectacular project. With this after-effect in mind, Geyer prompts us to reflect anew on the communicative potential–and limitations–of each medium of expression and to recognize the fragility of physical evidence, both historical and forensic, the difficulty amid the possibility of post-traumatic dialogue, and of course, the disturbing ease with which we become accomplices to the process of forgetting. Her choices and uses of media, combined with key sources quoted in the exhibit soundtrack–from actual court records to recorded testimony and passages from two books, Israeli prosecutor Gideon Hausner’s Justice in Jerusalem and German Emigre philosopher Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem: A report on the Banality of Evil-bridge ideological, as well as generational divides.3Thus, taken in toto, the sound/images gesture towards a cathartic space for healing past wounds for some, yet warn us as to the futility of remembrance if it is not productively plowed into conscious, collective action to guard against and confront the abuses of the present day. While the viewer may sit or stand alone as s/he repositions herself amid the display, s/he is likely to feel visually and aurally immersed in a public forum.

Humanity is the sovereign that has been offended.

-The Prosecutor, Criminal Case 40/61: Reverb

In her revisitation of the precedent-setting (yet seldom remembered) trial proceedings, writer-director-editor Geyer does not seem particularly invested in unveiling new evidence, nor in pushing for a definite moral or political stance with respect to the wartime atrocities (unnamed and never shown) and their modern day punishment.4 Yet those willing to look and listen will discover that the exhibit itself speaks unambiguously from a moral position, that of condemning all violations of human rights, with the Holocaust and its traces as a haunting point of departure. Universalization also carries the risk, Geyer seems acutely aware, of historical erasure. Given her oblique rendering of that history–the performances and photographic mises-en-scene have been distilled from an archive “in ruins”–we, as casual participants in the forum, are faced with a forking path. Either we can defer judgment, dig deeper with our own hands into that Holocaust history, and come face to text with the wholesale slaughter authorized by Eichmann; or we can meditate on the recent and cyclical analogues–Abu Ghraib, the Southern Cone in the late seventies and eighties, Bosnia in the nineties, Wounded Knee, the Congo, Darfur, Haiti, Arizona–that emanate from our active observation of the cross-examination of the accused, the judge’s verdict and sentence, and the ensuing philosophical debate, each of which is succinctly rendered in the video loop. Active spectatorship allows the Eichmann trial to figure as a template or precursor for other trials, either already past, perhaps incompletely resolved, or earnestly hoped for, and yet to be staged.

Andrea Geyer, installation view of Criminal Case 40/61: Reverb. Courtesy UAG/Room Gallery, UC Irvine. Photo: Robert Plogman.

Thus, what might at first appear to be an aesthetic of “avoidance”–the six characters in the video loop (the Judge, the Accused, the Defense, the Judge, the Prosecutor, the Reporter, and the Audience) are “subject positions” rather than people; the places of the trial and the crimes are never identified–points to the blind alley of limiting our scope of interpretation to the actual proceedings. This is not because Eichmann’s heinous actions and the larger, mercilessly authoritarian theater in which they were carried out don’t deserve enduring scrutiny, but because neither they, nor the trial that thrust them momentarily into the international limelight, can be effectively represented within any discrete spatiotemporal construct, no matter how accessible and copious the archive, voluble the witnesses, or generous the gallery space. To preserve the past in its wrappings and leave us gawking would be to let us, as alternately naive, evasive, critical, or complicit viewers (and by extension, Eichmann and his like) off the hook. Like Arendt’s querying of evil, human agency, and moral responsibility in her reflections on the trial, Geyer’s work is informed by an altogether different ethos than that which has framed most artistic and certainly all documentary journeys back to the Holocaust.5 It denies us the perverse pleasure, whether sadistic or masochistic, of looking at other people’s misery and maiming, as can easily occur with the countless explicit representations of the victims. The closest analog in cinematic form, albeit less allegorical and more graphic, are Alain Resnais’s ruminations through the abandoned spaces of Polish death camps in Nuit et Bruillard (Night and Fog, 1955), which provides just enough of a dose of the pain to propel us into resisting future signs of historical repetition. Above all, Geyer and Resnais suggest, we should not celebrate Eichmann’s horrific achievements–the display of damage done had its important moments at war’s end and in the context of the trial; rather we should take stock of how, insidiously, these acts can become the focus of a daily routine, supported by a (momentarily) functional chain of command. Geyer’s cautious, medium-distance framings, as well as the discontinuities in the technological formats of presentation speak to her concern with non-complacent viewing.

Andrea Geyer, installation view of Criminal Case 40/61: Reverb. Courtesy UAG/Room Gallery, UC Irvine. Photo: Robert Plogman.

As Elizabeth Cowie has observed, “all time-based works potentially give rise to the anxiety of the unremembered or missed, or misremembered; but for the video installation this potential is itself an aspect of its process and effect as art.”6 Throughout the installation, we find reminders of the limits of historical retrieval and our burden of thoughtful consumption, if we are to make any sense of it all, as we excavate, dust off, and mentally reassemble ideas and experiences that are not so much displayed or explained as “sampled.” This is but one of the multiple conceptual links in Geyer’s work to German cultural historian and philosopher Walter Benjamin: the Eichmann trial, overshadowed in the United States by the Bay of Pigs and the Kennedy assassination, can be likened to a “monad” which, “blasted out” of the historical “continuum,” sparks new transhistorical connections.7 The exhibit’s nondescriptive title, “Criminal Case,” foreshadows the deceptively bureaucratic demeanor of its contents, and invites us to begin naming the courtroom and identifying the crime. It is rigorously Modernist in its design–from the self-consciousness in the selection and presentation of sources and props, to the brazenly sparse mise-en-scene, which, like the staging of an Eugene Ionesco play, makes sources of excess (such as the phallic, “period” table microphones) readily stand out, adding a note of irony to the solemnity.8Meanwhile, the visual format and compositions in the videoplay seem almost iPhone friendly: carefully cropped medium shots with no detectible camera movement, a six-part ring of one-shots with dialogue in sync, and telegraphic intertitles that cater to a new generation that can neither remember nor forget any of the referenced crimes nor the drama that unfolds around them. The relation among these elements is neither contrived nor aleatory, but I think, potentially dialectical, if the Modernist underpinnings are to hold their sway: the veiled passion lacing the performances reverberates against the inertia of the “cold case” photos. One can detect (at least in the University Art Gallery staging) a hint of attentiveness to the interpretive possibilities generated by the gaps in content and medium overall, as well as syncopation in performative delivery.

Further facilitating the installation’s communicability, and accentuating its dual channel aesthetic are its multitemporal construction and transcultural possibilities. We glean these transportive traits from the casting, the intra-image set design, at once retro and New Wave, along with Geyer’s choice and deployment of presentational media, which yield different types of evidence (“traces” according to Geyer) and hail from different eras: still photography from the late nineteenth century; radio, the medium of popular choice in the thirties and source of live reportage during World War II; analog audiotape, from the McCarthy hearings and on into the sixties; to digitally edited and projected video in the new millennium. Like Nam June Paik’s multi-monitor installations, all of the technologies featured are relatively “low budget” and easily accessible, imaginable as domesticated objects.

The video performances, which are delivered across six channels of transmission on six LCD screens, periodically appear in a simultaneous “shot-reverse-shot” interplay among the various “characters,” thereby immersing the viewer, positioned at the epicenter of the display in the scene, so that the multilayered past can mingle with the present. (The video screens not only project and frame performances, but they themselves are “performing objects,” recalling the installation work of experimental architects Diller and Scofidio.9) Temporal reference points are inscribed in each mode of narrative presentation: the war itself remains buried under the 1961 cross-examination, while its remembrance by victims is delivered via a “radio” on a desk; the “Reporter” (Arendt in modern, New Yorker journalist “drag,” rather than middle-aged, professorial attire) editorializes the proceedings for today’s spectator, hovering between diegetic timeframes, while the “Audience”, characterized as a disaffected, youngish “male” figure, is similarly transtemporal, with the ambiguity reinforced by the framing of lone figures in frontal compositions using a slightly varied set. The six video “characters,” who are presumably of different nationalities, linguistic competencies, ages, and genders (with the bias, reflecting mid-twentieth century power structures, weighted towards the male gender) are performed by a single Asian American performance artist, Wu Tsang. In transgendering her roles through cross-dressing and delivering translated source texts in unaccented English, Tsang’s performances challenge extant identity gaps among the original participants, as well as any stereotypical images–of German Nazis, liberal Israelis, or court authorities–we, as itinerant viewers, might bring to the scene.

Flanking the video screen circle are pairs of headphones hanging from opposite bare white walls that allow us to listen to the soundtrack spoken by present-day actors in Hebrew, German, and, as the cultural “wild card,” Brazilian Portuguese, each of which positions us as eavesdroppers on both past and present, without drawing us directly into the proceedings (wearing headphones, the viewer can edge close enough to only one or two screens).

Finally, lined up on a wall in the rear section of the gallery, with their backs to the primary mise-en-scene, are seven 12-by-18-inch photographs of inanimate objects-the traces of the ongoing discursive framing of the trial, in histories, transcriptions, recordings, and debates. The first photograph (looking left to right), shows a stack of books in English and German on a desk, ranging from the journalistic to the philosophical, including the one written by Arendt, but also signed by, or about Bataille, Freud, Hegel, Kafka, Kant, and Karl Jaspers: The Camera Never Blinks, Politische Justiz, The Future of Being, Eichmann Interrogated, Reason und Existenz, Die Gerechtigkeit nehme ihren Lauf! Even as these photographs point towards the moment of the trial, and thus help us to “behold” its legacy, they are also meta-discursive, reminding us of the more traditional means whereby we gain access to the past–books and newspapers (photograph number 2); magnetic sound reels (photograph number 3); binders of notes or court records (photograph number 4); a radio (photograph number 5); documents, stacked and bound (number 6); and a period briefcase (number 7) that could have been used by trial attorneys, or by us, as we figuratively carry these traces with us. In this portion of the exhibit the past appears abandoned as a “cold case,” the details of which we must try at pains to pry open.

Even as our decipherment of these evidentiary fragments jolts us out of our forgetfulness, the tougher questions raised by Eichmann’s prosecution and cross-examination become a springboard for our free-form allegorical extrapolations. Can an individual be tried for “crimes of the state,” especially under authoritarian rule? Can one ever be technically “guilty” of committing such crimes, without being morally or socially “responsible” for them? Can the “truth” of genocide on this scale ever be located and publicly disclosed, even under oath? Can the law impede or put a rest to such atrocities?10Paradoxically, just as the fracturing, (re)framing, and staging of the continuous real disrupts our access to the empirical, our simultaneous distancing from and mesmerization with the mediated images are calibrated to transport us back out into the domain of living history. There is too much austerity and “audible silence” for this installation to nurture any kind of escapism. Hence, “reverbing” indeed, with the three media echoing yet complementing one another, creating room to test the durability of moral judgments in the face of ongoing human-made trauma. Under such conditions, the distinction between “factual” and “fictional” codes seems moot; Geyer’s montage, while dutifully observant of facts, is a dramatization without documentary pretensions.

Andrea Geyer, video still from Criminal Case 40/61: Reverb, 2009. Six-channel video installation, HD, color, sound, 42 min. Performer: Wu Tsang. Courtesy of the artist.

The use of time-based, multiple screen audiovisual projections (or, alternatively, the use of a split screen in film) to elicit reflections on the historical experience is hardly new: the concept was germane to media-conscious visual art and industrial-strength presentations of the sixties, as exemplified in Warhol’s serial “frame” paintings, title sequences to new Hollywood films (such as Norman Jewison’s The Thomas Crown Affair, 1968), special film projections at the 1964 World’s Fair in Flushing, New York, and of course Nam June Paik’s early installations (1966-69).11 Similarly, the notion that the technical apparatus used to project images not only affects the perception of image content, but the very form taken by the visual text, dates back, early film historians tell us, all the way to the late nineteenth century origins of cinema, when different modes of projection, from the Kinetoscope to the Cinematograph to the Mutoscope, competed with one another for industrial dominance. Recent examples of the self-conscious deployment of open-ended media in architectural space while referencing the historical also abound: there are the video testimonials in Kuba (2005) by Turkish artist Kutlug Ataman (described by Cowie), the video installations of experimental architects Diller, Scofidio and Renfro, and digital video films of Isaac Julien, for example, Fanon S.A. (1997) and Ten Thousand Waves (2010).12 What is ultimately innovative about Andrea Geyer’s work is that it bridges these constructs and their respective moments, while interrogating both the degree to which the historical can be productively retrieved through indexical or realist representations, and the extent to which spectatorial agency, promoted in controlled doses through kinesthetic interaction with display components, can lead to a shift in consciousness. Does a spectator’s voluntary response–to look, merely to glance, to look again, or stop looking–to the sensory stimuli emitted by a beckoning viewing/listening apparatus necessarily open up a space for cognitive dialogue and creative input? Or is it possible that the interactivity elicited by the guided choices offered by multimedia installations tends to supplant the viewer as the designated recipient of messages from a single, central source (the classic contemplative relationship to a work of art) with her designation as the still centric, albeit mobile subject, individuality intact, with “surfing” as the operative metaphor for the act of consumption?

Andrea Geyer, installation view of Criminal Case 40/61: Reverb. Courtesy UAG/Room Gallery, UC Irvine. Photo: Robert Plogman.

Geyer’s work accomplishes both and neither of these options: seated uncomfortably on a hard stool facing a pan-optiforum of recorded performances, we neither have the freedom of mobility that allows us simply to glance and ignore what is before us, nor are we straightjacketed into fixating onto the work–the Gaze so many theorists have puzzled over, and which is also conducive to fascist looking, listening, and learning. Geyer wishes to give us a taste of authoritarian strictures without taking away our wiggle room, and her circle of screens keeps beckoning us to turn our attention to yet another perspective on the matter before us. In this sense, she resists the controversial relativism of Arendt’s reasoning around the “banality of evil,” as well as any pretentious claims to “bringing back the past”–by unveiling incontrovertible facts–that many Holocaust documentaries, like so many other historical documentaries, indulge in. There must be room for the deviations unleashed by sheer affect–of guilt, revulsion, loss, grief–even if, as Geyer seems to argue, to foreground these melodramatically might yield too much pleasure so as to distract the viewer from the transhistorical task at hand. Refreshingly devoid of abject images of the injured, starved, or limp, while pointing to the yawning chasm left by so many who did not live, her work also resists heroicizing Eichmann while subjecting him to our renewed scrutiny; we listen mainly to his cross-examination along with prosecutorial summations, even though, according to the DVD recording of Geyer’s work, over sixty percent of the trial was devoted to victim/witness testimony. Does the installation excessively silence the voices of those who suffered? Perhaps. And yet, notwithstanding its evident stagings and fictional rendering of characters, Geyer’s work does not shirk the burden of factual fidelity. Instead, it urges us to seek the truth, which is complex, even plural in nature, once we have brushed shoulders with the trial’s scripted and actual protagonists. This response is vitally necessary if the video loop is not to become a self-enclosed, vicious circle; to paraphrase John Handhardt, who is quoted above–irreversible yes, but finite, certainly not. A note of sober optimism can be sensed at the circle’s edge: “what good will it do?” queries an intertitle of the reenactment when it has barely begun; the answer: “will do justice.” And what is justice without timely confrontation and deliberation, under the spotlight of a public forum?

Andrea Geyer, installation view of Criminal Case 40/61: Reverb. Courtesy UAG/Room Gallery, UC Irvine. Photo: Robert Plogman.

Catherine Benamou is associate professor of Film and Media Studies/Visual Studies at the University of California, Irvine, and the author of It’s All True: Orson Welles’s Pan-American Odyssey (University of California Press, 2007).