William E. Jones, “Killed,” 2009. Still from video sequence of digital images, black and white, silent, 1:44, looped. Courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

In William E. Jones’s silent video “Killed” (2009), a two-minute sequence of 130 appropriated black-and- white stills replays six times in rapid-fire progression on a continuous loop. Each still is a Farm Security Administration (FSA) documentary photograph, taken between 1935 and 1939. What distinguishes these photographs from others of the renowned U.S. government-funded photography project is that the negative for each was hole-punched, signifying rejection by the agency’s head. The resulting puncture, which rendered the negative unprintable as a seamless document, features prominently in the piece as both a mesmerizing graphic element and as an invocation of the ghosts of social documentary photography. With “Killed,” Jones elicits a reconsideration of documentary photography as an agency of social awareness and as an art–not in the interest of reviving it in the literal sense, but out of regard for the type of attention to the social landscape exemplified by the genre. Reconsideration is timely in light of the parallels between the Great Depression and our own trying economic times, and unusual in the self-reflexive climate of the contemporary art world. “Killed” is a curious detour for an artist known most recently for excavating hidden gems from gay pornography in a series of found footage videos. What connects “Killed” to these earlier projects is Jones’s commitment to dusting off neglected corners of visual culture to unearth clues to places, people, and moments in history that may be too easily taken for granted in an era of seemingly limitless access to Internet content. “Killed” was first displayed at David Kordansky Gallery in Los Angeles, as part of the group show Matthew Brannon, Marcel Broodthaers, James Lee Byars, William E. Jones, and then presented on a continuous loop in the Box video gallery at the Wexner Center for the Arts in October of 2009.

Based on their resemblance to other credited photographs of same or similar content, the stills from “Killed” can be attributed to FSA staff photographers Walker Evans, Theodor Jung, Carl Mydans, Marion Post Wolcott, Arthur Rothstein, Ben Shahn, and John Vachon.1 All of the above were hired by the Historical Section of the Resettlement Administration, later named the Farm Security Administration, which was an office within the US Department of Agriculture. The FSA photographs, produced between 1935 and 1942, are classic examples of social documentary photography, and a massive record of depression-era America by some of the best-known photographers from that time. The project was the brainchild of Roy Stryker, head of the Historical Section, and its ostensible purpose was to publicize the FSA’s rehabilitation programs, as well as to depict the rural poverty that necessitated those programs in the first place. But the images themselves are collectively much more diverse in subject matter and purpose. In the words of the Library of Congress Web site, where many of the approximately 165,000 images can be viewed, they “form an extensive pictorial record of American life between 1935 and 1944.”2 Perhaps most significantly for our time, they represent a massive, taxpayer-funded body of images. The project as a whole could even be considered a public art project, if one believes–as Stryker largely did not, but Jones apparently does– that documentary photography qualifies as art.

Stryker himself coined the term “to kill,” and along with an assistant he administered the hole-punch.3 Stryker is an ambiguous figure who comes across in historical accounts as on the one hand a patron of his agency’s talent, and on the other an autocrat.4 The stills in “Killed” represent a very small subset of the FSA archive and require extensive searching to locate online. The photographers whose negatives were “killed” were themselves a subset of Stryker’s staff of photographers. As Jones points out, the work of some of them–Jack Delano, Dorothea Lange, and Russell Lee–may never have been subjected to the punch. After 1939, Stryker softened his method of killing photographs: rather than damaging the negative, he tore a small corner of the print, which afforded photographers the opportunity to challenge his editing decisions.5

William E. Jones, “Killed,” 2009. Still from video sequence of digital images, black and white, silent, 1:44, looped. Courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

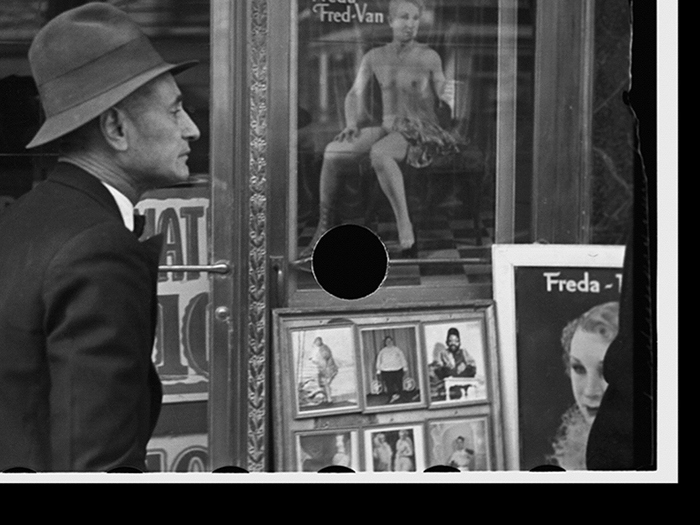

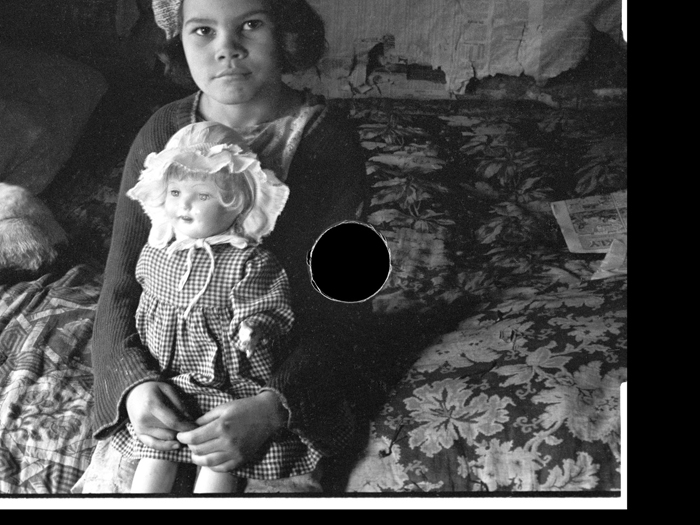

Visually, Jones’s framing of the “killed” stills centers around the punched hole itself: a black circle whose enlarged and slightly ragged nitrocellulose edge pulsates when animated. As a repeated motif in “Killed,” this hole is beautiful in its analogue imperfection, darkly erotic if one views it in the context of Jones’s other work, menacing in its dominance over the images whose content it obscures, funny as a purely abstract animation, and hypnotic at the moments when one becomes drawn into the rhythm of its repetition. As the video begins its first cycle, each still is enlarged and cropped to allow the hole, placed dead center, to dominate the frame. Only grainy image details are revealed: a section of hand-painted sign, a flicker of gingham fabric, a child’s pursed lips.

With each cycle, the hole progressively diminishes and then grows in size but remains in the center, which is a structural “rule” Jones has set for the piece. As the view widens, one glimpses rural families, crowded street scenes, modest wood-frame houses, and storefront signage, all reminiscent of the FSA’s typical style and subject matter. The exception is the last cycle, during which each photograph is fully revealed, this time for a more prolonged beat of time. Here the photograph itself, and not the puncture, occupies the center of a black border within the video’s frame, revealing the arbitrary location of the hole, which dances merrily around the image like the bouncingball in vintage sing-along cartoons. The pace of the animation is such that no single image can be satisfactorily viewed, identified, appreciated, or understood, an effect that thwarts our natural inclination to want to see the details of pictures that 75 years ago were branded unworthy.

The near-obsolescence of the embattled genre of social documentary photography is a sub-theme of “Killed.”6 Jones was a documentary-style still photographer early in his 20-year career, and completed a series of color images of vernacular architecture in Southern California only ten years ago.7 Elegiac references to classic forms of analog photography, or the memories associated with the images and with the rituals of the darkroom, can be found in other important works by experimental filmmakers that address different aspects of this history, including Hollis Frampton’s Nostalgia (1971) and Judy Fiskin’s The End of Photography (2006).

William E. Jones, v. o., 2006. Still from color video, sound, 59 min. Courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

Even more fascinating—and just as relevant to the subject of “Killed” as the direct references to the legacy of documentary—is Jones’s work with found footage in video works such as The Fall of Communism as Seen in Gay Pornography (1998), All Male Mash Up (2006), and v.o. (2007).8 In the latter works, Jones’s use of non-synchronous sound and narrative innovation places him in the company of avant-garde filmmakers such as Kenneth Anger, Bruce Connor, Peter Roehr, and Scott Stark. But these works also function as gestures of critical appreciation for the documentary evidence his source material provides. As Jones narrates in the opening scene of The Fall of Communism as Seen in Gay Pornography: “Even in an unlikely place, it is possible to find traces of recent history.”

The above mentioned videos constitute a re-mix of footage from gay porn movies of the pre-AIDS era, some of which Jones encountered while editing gay porn compilations for Larry Flynt Publications as a job for pay. They invert the narrative expectations of porn by focusing not on the sex, but on the interstitial moments that fill the gaps between; they are scenes, as Jones himself describes them, that don’t just depict “things going into holes.”9 In The Fall of Communism as Seen in Gay Pornography, for example, Jones zooms in on the facial expressions of youthful actors, who inadvertently reveal their awkwardness and vulnerability, as well as helpless anger, in response to the coercive circumstances of their employment. All Male Mash Up features an elaborate montage of shots from the red light district of Times Square, where peep show advertisements, porn theatre marquees, and adult bookstores form a collective portrait of the marriage of desire and commerce.

William E. Jones, “Killed,” 2009. Still from video sequence of digital images, black and white, silent, 1:44, looped. Courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

v.o. in particular contains footage of urban landscapes that are rich in detail and ambience. For the piece, Jones paired scenes from 12 porn movies with sound clips taken primarily from classic European avant-garde films. Early in v.o., extended shots of Hollywood’s hustler district from L.A. Plays Itself (Fred Halsted, 1972)10 linger over fast food signs; billboards; slow-moving cars on wide, congested streets; a crowded newsstand; and pedestrians and hitchhikers against a backdrop of humble storefronts and street corners. A scene from Peter Berlin’s That Boy (1974) depicts a slow seduction between two men set against the working class, light industrial South of Market neighborhood in San Francisco, in which windowless warehouses, a pink stucco sandwich shop, and a deserted alley are as much characters in the scene as its self-consciously sexy leads. The shots index the slower pace of life in the ’70s, the aimlessness of porn narratives, and the influence of still photography. Thanks no doubt to low production budgets, these backdrops for characters who cruise on foot and by car offer documentary “clues” to settings that figured strongly in gay life in the cities depicted. Images by FSA photographers such as Shahn, Delano, Evans, Post Wolcott, and Vachon are precedents for these deceptively ordinary glimpses of street life that are elevated by the camera’s studied gaze.

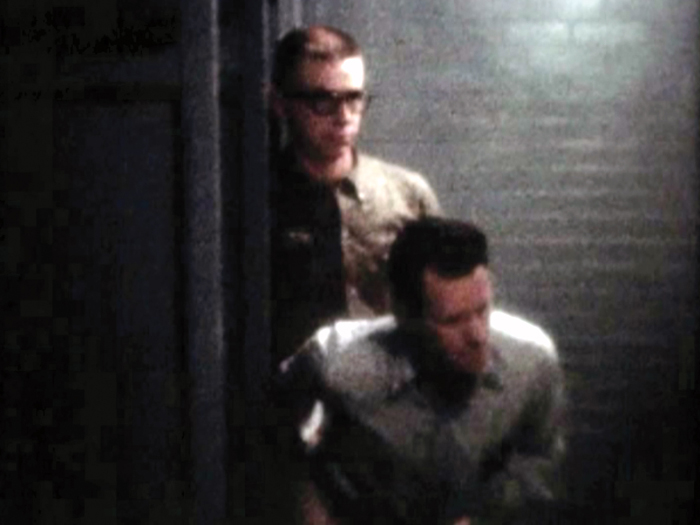

William E. Jones, Tearoom, 2007. Still from color video, silent, 56 min. Courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

Similarly, Jones’s Tearoom (2007) depicts the manifestation of repressed desire in the humblest of public settings. Tearoom presents, in practically unaltered form, a 16mm police surveillance film from 1962 of men having sex in a public restroom in Mansfield, ohio. It contains nearly an hour’s worth of furtive and apparently joyless sex. Its power hinges on the implications of content suppressed from public view and used for unjust purposes, since the original film served as evidence to convict many of the film’s subjects of sodomy, criminalized in Ohio until 1974. As with “Killed,” Tearoom discloses a visual history of people in high-stakes circumstances, ones in which livelihoods and personal freedoms hung in the balance.

One could draw a comparison between Jones’s revelations of documents from gay cultural history and his excavation of the “killed” FSA photographs from the Library of Congress’s labyrinthine Web site. Although scholarly speculation into why Stryker destroyed the “killed” negatives indicates nothing more malicious than a short-sighted approach to editing that stemmed in part from ignorance, the obstructive/destructive mark stokes one’s natural curiosity–curiosity that inspired me to scroll slowly through the paused video to view each of the 130 stills. This option, it must be noted, is not available to the gallery visitor, although I would argue that it enriches the context for the work by offering glimpses into a largely unknown cache of treasures from the FSA archive.

William E. Jones, “Killed,” 2009. Still from video sequence of digital images, black and white, silent, 1:44, looped. Courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

The subjects of the “killed” photographs seem initially unremarkable, but multiple viewings reward the patient eye. In one image a poor newspaper salesman stands static in the street and smiles enigmatically at the camera as a trolley passes behind him. Another shows a well-dressed woman lost in thought amongst a crowd of people gazing outside of the frame; an American flag waves behind them. Multiple views of dilapidated storefronts displaying a density of wares disclose telling details about consumer and pop culture in the 1930s. Some pictures appear carelessly composed, or technically flawed, but they are by no means uninteresting: a radically canted view, several completely blurred images, and a few underexposures, including one of a heavyset women in a cafe wearily wiping a sweaty brow, or perhaps crying. others are strong by conventional art-photography standards. For example, in a farm scene attributable to Vachon, two girls in identical print jumpsuits stand knee-deep in a lush crop, gazing at the camera in the lower left section of the frame. The figures are balanced by an unfocused image of a vigilant farmer on the right.11

Further viewing yields images of African Americans that contain telling reminders of racism, for example, a photograph by Vachon of two boys, one with a mournful expression, who sit on the bed of a wagon. Behind them, a small sign reading “COLORED” is nailed to the trunk of a tree near a drinking fountain.12 Also included are three striking images by Jung, whose FSA career was short-lived. These depict a young, light-skinned, African American girl sitting on a bed, her arms encircling a doll with blond hair.13 The one that depicts the subject with a half-smile on her face exudes that rare presence of spirit, and is among the more compelling FSA photos I have viewed. In the category of potentially suppressed gay content, a photograph taken in Washington, D.C., depicts the profile of man in a fedora hat passing a storefront that displays a framed photo of a topless male-to-female transsexual performer with one full-looking breast.14 Another of two middle-aged white men staring at one another (one rather wistfully) from the windows of separate cars15 evokes the furtive glances of the men having sex in Tearoom.

William E. Jones, “Killed,” 2009. Still from video sequence of digital images, black and white, silent, 1:44, looped. Courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

The actual pace of the animation eludes careful study of each punctured still, unless one has the luxury of pausing the video at will or watching many, many repetitions. This raises the question of Jones’s intentions for the video, particularly given the pace of his other work, which is so clearly about revelation and not obfuscation. Judging by the aesthetic and political statements he made when he presented the found footage of Tearoom, the artist believes that content suppression is condemnable, even the kind whose purpose might be to keep one’s private secrets from public view. While Tearoom represents full disclosure, “Killed” appears to obscure.

As an image-saturated work played at a speed that outpaces image recognition, “Killed” accomplishes a form of revelation through double concealment. We, image-savvy viewers accustomed to unlimited, 24-7 access to a wide range of content from the politicalto the prurient, find ourselves denied easy entry.Photography’s relevance as a locus of meaning–social, aesthetic, historical, or otherwise–is the subtext of the piece. Stryker’s holes confront us with questions: not just the obvious one of who has the right to discern the value of one image over another for posterity, but of which images will survive in the public realm as evidence of our time. Will visual documents of communities formed in public space–however one chooses to define those entities–even matter?

Audrey Mandelbaum lives in Los Angeles.