Edgardo Aragón, Tinieblas (Darkness), 2009. Thirteen-channel video installation, sound, 7 min. loop. Installation view, Modos de oír: prácticas de arte y sonido en México (Ways to Hear: Art and Sound Practices in Mexico), Ex Teresa Arte Actual, Mexico City, November 29, 2018-March 31, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Ex Teresa Arte Actual. Photo: Gerardo Sanchez.

Loud and Messy: Sound as Diagnostic

The sound of hovering helicopters fills the vaulted ambulatory of a decommissioned basilica in the historic center of Mexico City. The work by Israel Martínez, titled Acorralado (Cornered, 2012), plays intermittently from speakers placed in the second-floor balcony. It is one of more than one hundred artworks that fill two venerated spaces, Laboratorio Arte Alameda (LAA) and Ex Teresa Arte Actual, as part of the collaborative exhibition Modos de oír: prácticas de arte y sonido en México (Ways to Hear: Art and Sound Practices in Mexico).1

Eliciting a sense of foreboding, Acorralado uses sound to confront the viewer, and its variable volume heightens the sense of anticipation.2 While the work’s backdrop, as noted by the curators, is the militarization that characterizes the drug war and government surveillance, it remains more open ended: there is rhythm, drone, glissando. And there is the query unique to sound: What is that noise?3 Where is it coming from?

Embedded in these questions and fundamental to any mode of hearing are the role of the body and the importance of technology as an instrument of making, amplifying, and recording sound. This dual anatomy of decipherment—the listener and the machine—links sound to a rhetoric of progress, as represented by both language and engineering; it also underlies sound’s long association with the occult and its invention of heterodox systems for perceiving the unseen. Occult comes from the Latin to hide, and in this sense sound has a long history of being associated with the supernatural and myths of all kinds, where the perception of aural resonance is analogous to a kind of phenomenology of the invisible. Sonic vibrations in this context embody proof of being alive and therefore link humans and animals with all nature via a registration of energy. In this way, sound provides a kind of metabolic glue linking different and at times antagonistic forces, functioning very much like an ecology and in effect becoming the basis of a social body.4 In light of this, Jacques Attali asserts, in his seminal Noise: The Political Economy of Music, that sound has the ability to “affirm society is possible,” arguing, “It is a herald, for change is inscribed in noise faster than it transforms society . . . demonstrating music is prophetic and that social organization echoes it.”5

Edgardo Aragón, Tinieblas (Darkness), 2009. Thirteen-channel video installation, sound, 7 min. loop. Installation view, Modos de oír: prácticas de arte y sonido en México (Ways to Hear: Art and Sound Practices in Mexico), Ex Teresa Arte Actual, Mexico City, November 29, 2018-March 31, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Ex Teresa Arte Actual. Photo: Gerardo Sanchez.

This ability of sound to announce what is hidden, both physically and sociologically, lies at the heart of Modos de oír and the concurrent exhibition Constelaciones de la Audio-máquina en México: Ruinas y reconstrucciones de una historia sónica (Constellations of the Audio-Machine in México: Ruins and Reconstructions of a Sonic Story), which took place in the neighboring state of Morelos.6 Timely and provocative, both exhibitions explore the dynamic relationship between sound and what ethnomusicologist Alejandro L. Madrid describes as “an identity and cultural crisis within the essentialist project of the Mexican Nation.”7 In response to this diagnosis, and what anthropologist Tarek Elhaik calls “the post-Mexican condition,” the curators have created two diverse exhibitions organized around different but overlapping sets of categories that examine what ails Mexico and posit a curative based in its rich history.8 The exhibitions explore these themes through not only sound recordings but also sculpture, video, installation, printed matter, and performance.9

Ways to Hear: Curation as Cure

In both exhibitions, the curators seek to outline this “post-nationalist” crisis in Mexico by overlaying the advent of sound technology and its many permutations in the country throughout the twentieth century with the evolution of modernism that followed the Mexican Revolution (1910–18).10 This framing rests on Madrid’s assertion: “Sound has played an essential role in the creation of our nation’s myths and in the construction of a collective experience in response to the illusion of progress.”11 By engaging such a broad time period, beginning with the advent of recording technologies in the late 1880s and continuing up to the present, both exhibitions attempt to chart the extent to which sound has played a role in formulating and disseminating iconic tropes of Mexican identity. This forensic approach to sound echoes Tito Rivas, one of the curators of Modos de oír, who argues that an “archaeology of sound is, above all, an archaeology of listening.”12 This rubric of a post-mortem can be seen in both exhibitions and was highlighted by the curators’ pronounced use of categories, which spoke less to a clear taxonomic analysis than a tangled knot. Navigating both spaces, I was struck by the poignancy of archaeology as evocative not only of hidden layers but also and more profoundly of dismemberment, wherein many subjects of Mexican history are seen as cut off, silenced, or buried.13 Not to belabor the analogy, but because Modos de oír was installed in two spaces and the works were not necessarily installed neatly according to their category, my reading of the various pieces and my understanding of their interrelationships was itself fragmented. This echoes the “open-ended” approach of the curators and reflects my own position as an outsider. It also foregrounds my view that the primary subject of both exhibitions was as much the curatorial project itself, as outlined broadly in terms of Mexican identity and history, as it was sound or even art. This tension between the curatorial framework and the autonomous works frames my review.

Pebellón Fonográfico (Phonographic Pavilion), exhibition space and listening station, designed by Mauricio Rocha. Installation view, Modos de oír: prácticas de arte y sonido en México (Ways to Hear: Art and Sound Practices in Mexico), Ex Teresa Arte Actual, Mexico City, November 29, 2018-March 31, 2019. Courtesy of Ex Teresa Arte Actual. Photo: Gerardo Sanchez.

The curators’ diagnosis of Mexico as sick and in “moral crisis” is informed by a body of criticism that argues that contemporary Mexico is subject to what Elhaik calls a “malaise” and fellow anthropologist Roger Bartra characterizes as “melancholia.”14 Elhaik proposes that the primary symptom of this illness is what he terms an “incurable-image,” defined by a fractured, impossible to realize post-colonial identity. This analogy of a hybrid body links my argument that sound is based on a “dual anatomy” with Madrid’s statement: “If the most successful representations of modern Mexico throughout the first half of the twentieth century were borne out of the unexpected marriage of the indigenous and the machine, one could interpret that representation as a type of discursive cyborg that dominates the Mexican imagination.”15 This diagnosis that the nationalistic myth of modern Mexico is an incurable ideal—defined by the fraught poles of indigenous and modernist signifiers—underlies both exhibitions and fundamentally informed my experience of the broad range of works in the shows.16

Mexican Phonography: A Supranatural Hybrid

Viewing Mexican identity and sound art as a discursive cyborg foregrounds the way music has been understood for millennia as a medium—connecting the body, ritual, and technology—that can be deployed in order to heal.17 Sound in this respect is a kind of proto-technology, leading first to expression, then to language and the naming of things, and later to instruments and tools of all kinds. In these exhibitions, sound can be understood as embodying both legible media and something more akin to what people describe as supernatural. This conceit of sound as revealing deeper truths about nature or the universe informs the analogy of the cyborg as a supranatural hybrid and more generally the implicit curatorial argument that sound might hold a key to curing the crises of Mexican identity. This question of Mexican culture as having its origins in sound seems especially relevant to the framing of Modos de oír, as it is literally installed in two desacralized churches in el centro, steps from the ruins of the Aztec Templo Mayor. These churches were originally built to announce Christian dominance and, despite having little or no religious iconography remaining, they still link directly to the colonial practice of building on top of and renaming pre-Columbian sacred sites, which is precisely what happened in Tenochtitlan when Cortez invaded the city.18

The role of architecture in creating an ontological system is evident not only in the basilica floor plan but also in one of the curatorial categories in Modos de oír: the Pebellón Fonográfico (Phonographic Pavilion). Designed by architect Mauricio Rocha and installed in the central nave of Ex Teresa, the massive Pavilion is a large spiraling ramp inspired by the cochlear form of the inner ear, a shape that conveys an aura of the body and of ritual symbolism. Built of unfinished wood, the structure fills more than two-thirds of the space and rises more than forty feet into the air, allowing the viewer unprecedented proximity to some of the architectural details and murals that cover the ceiling—a perspective that also directly engages the church’s acoustics and highlights how sound has been used to literally amplify myth.19

The Phonographic Pavilion houses a mini-exhibition of recordings that offer what can be seen as a cross-section of Mexico’s twentieth-century culture. Listening stations are situated at regular intervals as one ascends the Pavilion; each consists of a plywood kiosk embedded with a small speaker and accompanied by a short written description. Not strictly chronological, their order posits a conceptual arc, tracing relationships between Mexican history and technological innovation. Here are a few examples, as encountered moving upward from the base: Huichol Indians singing sacred songs (1898), recorded by anthropologist Carl Lumholtz, described as the first recording ever made in Mexico; IU IIIUUU IU (1924), by Luis Quintanilla (AKA Kyn Taniya), who is described as an estridentist poet and a pioneer of radio art in Mexico and whose poem collages snippets of actual newscasts with lo-tech sound effects; Mushroom Ceremony of the Mazatec Indians of Mexico (1956), by Gordon Wasson and María Sabina; and Cuelgan de los puentes (Hang from Bridges, 2015), by Tito Rivas.20 This last piece is described as a reconstruction of cell phone calls from the massacred students in Ayotzinapa, and it combines fuzzy recordings of shouting men and what sound like gunshots with a voice-over memorializing the tragic event, which continues to haunt Mexico. Cuelgan de los puentes takes advantage of both sound’s capacity to record concrete evidence and its ability to provoke catharsis, and the piece is noteworthy for being one of the most explicit political statements in either show.

As the singular point of origin in the history of recorded sound in Mexico, the a cappella Huichol songs powerfully evoke the history of their original recording and, by extension, colonial history and its legacy of ethnography. They also speak to sound’s ability to conjure the unseen, not only the dead but also, in this case, something metaphysical, as embodied in the song’s purpose. The didactics indicate that these songs were originally sacred, part of a complex cosmology that includes ritual synthesis of sound and visual art to connect with the spiritual realm, but unfortunately, the exhibition does not address this cultural context and the way colonialism has impacted Mexican history more broadly. These abbreviated didactics represented a missed opportunity to ground the curators’ argument in the social milieu of Mexico, which was frustrating given the Pavilion’s overall powerful presentation. Sung in a language that is totally unfamiliar to me and, no doubt, most Mexicans, the Huichol songs inevitably took on a more abstract formal beauty, eliciting pure sound divorced but not devoid of meaning. As strictly sound, the voices raise compelling critical questions of what meaning remains when language fluency is lost.21 Indeed, while never explicitly framed by the curators of Modos de oír, the role of indigenous voices in formulating the Mexican imaginary is planted here as a foundational aspect of experimental sound art’s interest in occult idioms.

The layout of Constelaciones more clearly articulates Mexico’s sonic origin, making it the subject of its own category: Indio-futurism. The exhibition also illustrates how artists and composers made concerted efforts after the Mexican Revolution to acknowledge and incorporate indigenous music and art in new forms; whether these gestures of solidarity are seen as self-serving or genuine is a litmus test that continues to divide audiences today.22 Installed in a more traditional museum environment in Cuernavaca, Constelaciones’s presentation of this aural history often takes the form of original notated scores and old photographs, including Carlos Antonio de Padua Chávez y Ramírez’s El fuego nuevo (The New Fire, 1921) and Sinfonía india (Indian Symphony, 1935–36), the latter a symphonic work that calls for Yaqui percussion.23 The ballet Paraíso de los ahogados (Paradise of the Drowned, 1958), choreographed by Guillermina Nicolasa Bravo Canales to indigenous ceremonial music recorded by American folklorist Raúl Hellmer Pinkman, pushed this synthesis even further. It was hard not to interpret the ballet, which collapses ethnography and the avant-garde, as a kind of secular ritual or, indeed, discursive cyborg, especially given that it includes costuming and props (depicted here in photographs) that showcase the dancers inhabiting a puppet form inspired by the Meso-American feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl.

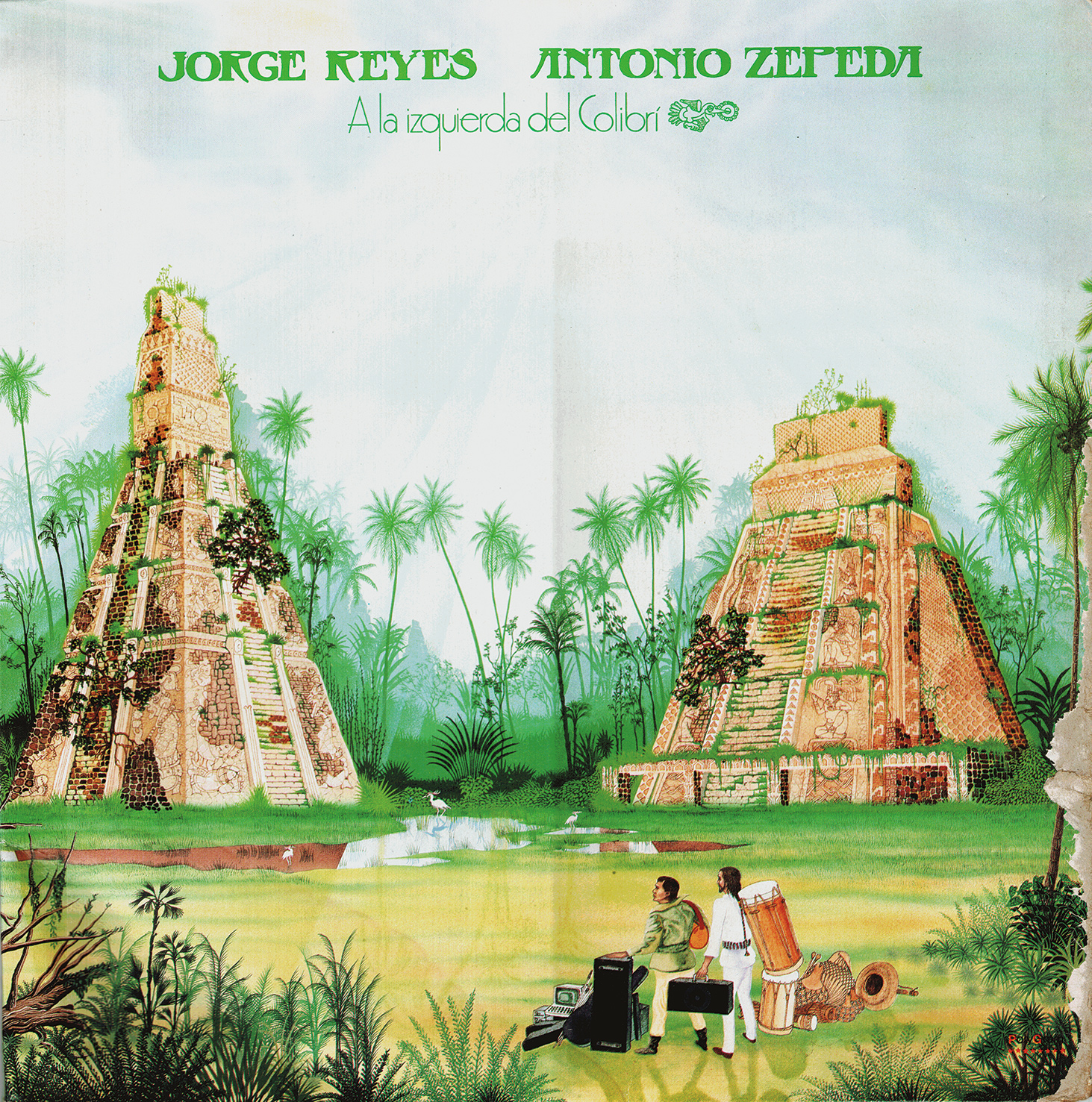

In my opinion, the whistles, beeps, and incantatory sounds used in many of the early radio plays and more contemporary electronic sound art works presented in both exhibitions (but framed most clearly in the Pavilion) can be under- stood as related to how native peoples understood sound as an occult tool. That is to say, the songs are intended to facilitate a ritual event and, therefore, are not functional in a secular playback. As such, what we hear might as well be the fictionalized sounds of spaceships and aliens. When adopted by artists, it raises questions not only of cultural patrimony but also and more simply of how sound can affect a secular ritual experience. Madrid makes these points expressly in citing indigenismo as central to Mexico’s modernist myth and malaise, as does Prieto Acevedo. The latter curated his own archive in Constelaciones consisting of album covers as art (framed hanging on the wall) and reference library (displayed together in a vitrine). In both modes of presentation, the LPs provided a reminder of how contemporary rock, jazz, poetry and new age genres all exploited this romantic intermixing of indigenous and futurist symbolism. For example, the cover of Jorge Reyes and Antonia Zepeda’s A la izquierda del colibrí (To the Left of the Hummingbird, 1985) depicts two hip musicians playing their instruments amongst Mayan ruins. This classic album layers traditional native flute and chants with drum machines and synthesizers.

(Living Voice of Mexico) held at UNAM (Autonomous National University of Mexico). This collection focuses primarily on the voice of writers and poets from Mexico and Latin America. To hear examples: https://www.cecilia.com.mx/index.html. Background left: Pablo Lopez Luz, Vista Aérea de la Ciudad de México (Aerial View of Mexico City), 2012. Inkjet prints, 23 x 23 in., series shown as projections in the exhibition. Courtesy of Carlos Prieto Acevedo.

Paraíso de los ahogados (Paradise of the Drowned), 1958. Choreographed by Guillermina Nicolasa Bravo Canales, design by Raúl Flores Canelo. Performance of Ballet Nacional de México. Courtesy of Carlos Prieto Acevedo.

The curators in both exhibitions foreground the way sound often appropriates different voices and how Mexican artists and intellectuals have exploited this promiscuity throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries in the name of progress. By juxtaposing artists with ethnographers and engineers, the Phonographic Pavilion is especially successful in framing the extent to which sound is always located within and between culture, especially in terms of mingling the metaphysical themes of indigenous groups with the nascent science fictional genres of radio and film. Unfortunately, poor quality speakers and the cavernous, stone environment of Ex Teresa result in a noisy playback experience for listeners, who struggle to differentiate one recording from the next. A common enough problem when installing sound art, the distorted and intermingling sounds that fill the church underline, perhaps subconsciously, that Mexican modes of hearing resist easy categorization or even legibility. In this, the Pavilion succeeds admirably in presenting sound as a mutated form ill-suited to encyclopedic gestures. I only wish the curators had pushed this logic to its extreme and erected the Phonographic Pavilion cum Tatlin Tower of Babel outside, thereby allowing it to take root in its native habitat—the street.

In the Field: The Street as Living Archive

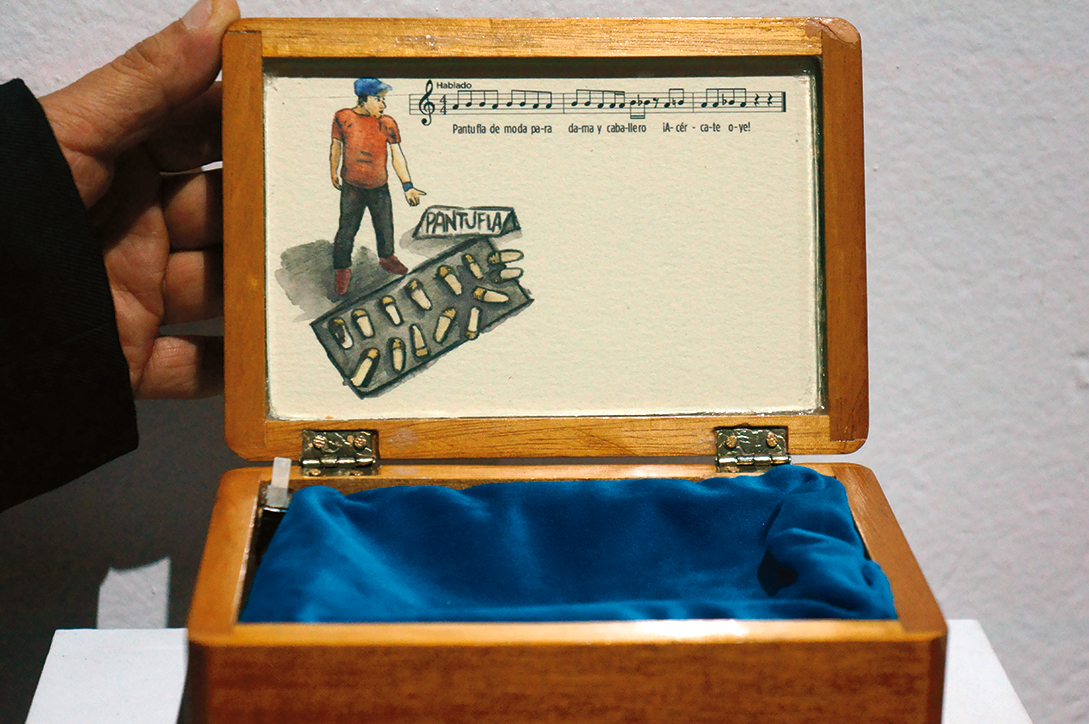

This suggestion isn’t made idly. The street and popular culture are paramount when discussing sound in Mexico, and the curators acknowledge this in terms of both the poetics and politics of the local. The way sound resides in and reveals a place is a key principle in the advent of field recording and the importance of radio beginning in the early twentieth century.24 This tangled legacy can be seen clearly in the history of ethnography and its use of recording in the field to justify or obscure Western colonialism. Forever linking indigeneity and racist social theories to enlightenment ideals of taxonomy, this impulse to catalog and preserve local sound can be seen as a fundamental point of tension, where economic or cultural value is assigned to what is otherwise free or shared, a subject that is intimately tied to the street. It also establishes field recording as a powerful medium for celebrating and preserving at-risk voices, including folk genres, as well as a tool for monitoring a place’s ecology. Examples of this kind of interdisciplinary practice can be seen in both shows, in the works of artists who see field recordings as a technology uniquely suited to reveal marginal or hidden sounds.25 The street is certainly captured alive in a poignant piece by Félix Blume and Daniel Godínez Nivón, Coro informal (Informal Chorus, 2014), a series of ten small wooden boxes in Ex Teresa. When a gallery viewer opens them, the boxes play the exuberant sales pitches of various street vendors. The hawkers’ voices discordantly fill the hallowed gallery space, suggesting the ways sound can designate space in an otherwise chaotic milieu and linking it to agency and ritual orientation, as well as economic exchange and health.26

Jorge Reyes and Antonia Zepeda, A la izquierda del colibrí (To the Left of the Hummingbird), 1985. LP cover, concept and design by V. Hugo Lopez Gonzalez, Philips Records. Courtesy of the artists.

Félix Blume and Daniel Godínez Nivón, Coro informal (Informal Chorus), 2014. Series of 10 music boxes made from wood, mechanical instrument, ink on paper, 5 x 8 x 4 in. Courtesy of the artists and Ex Teresa Arte Actual. Photo: Gerardo Sanchez.

The video installation in Ex Teresa titled Tinieblas (Darkness), by Edgardo Aragón (2009), also considers the politics and poetics connecting sound and place. Thirteen vertical monitors are arranged dramatically in a semicircle in the church’s ambulatory. Each monitor depicts a musician standing on a rock gatepost in a rural region of Oaxaca and playing separate parts of a funeral dirge. Standing alone on these modest territorial ruins familiar to any frontier, the figures and their plaintive playing imply a deep nostalgia for an earlier and more heroic period in Mexico, when people’s identities and songs were tied to the land. For me this work also echoed North American clichés of “the West” and illustrated how the popular histories of both countries overlap in significant and meaningful ways. Indeed, the work poignantly evokes not just the legacy of colonization but also how land disputes and economic pressures continue to force rural Mexicans away from their ancestral homes and into cities.

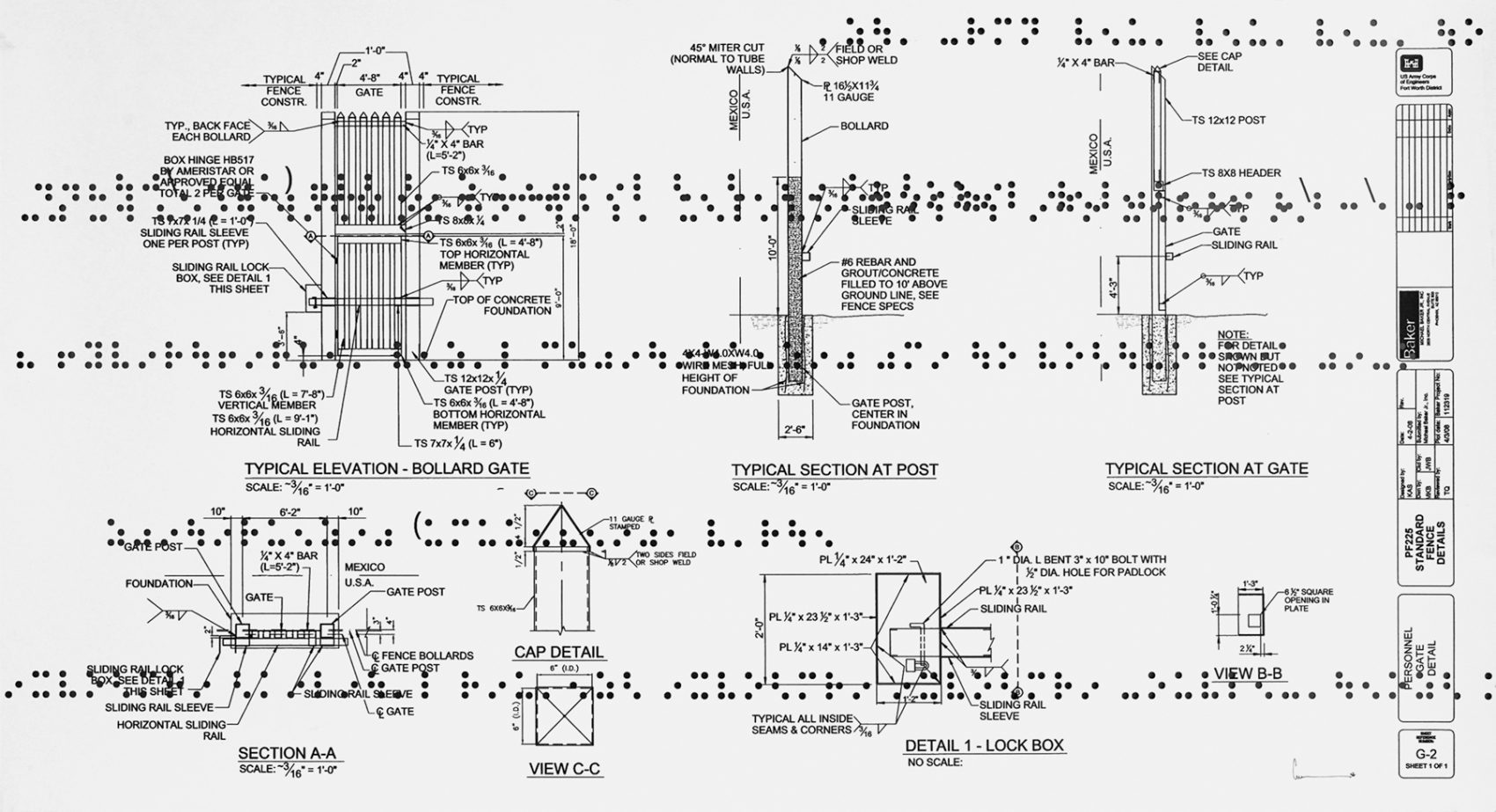

A series of projected photographs by Pablo Lopez Luz conceptualizes this ongoing migration—perennially in the news but little understood outside of its impact on the US/Mexico border—as a kind of socio-geographical cut-up. Titled Vista aérea de la Ciudad de México (Aerial View of Mexico City, 2006) and installed in Constelaciones, the series captures the epic scale of overpopulation and urbanism gone amuck. Signified by densely built, cheap concrete houses that stretch as far as the eye can see, this transformation suggests a kind of urban cyborg where the landscape is altered beyond recognition. Echoing a psychogeography, this interest in revealing hidden aspects of place is at work in Guillermo Galindo’s collages, in Constelaciones, in which the artist/musician places graphic notation systems directly on top of US-Army-issued blueprints for building security walls along the Mexican border. This allusion to how land can be both sacred (evoked in song) and profaned (arbitrarily demarcated) is also explored in the haunting film Judea, Semana Santa entre los Coras (Judea: Holy Week among the Cora, 1974), by Nicolás Echevarría, exhibited in Ex Teresa. Judea documents indigenous Cora men celebrating Easter by staging a mock battle between good and evil that spreads throughout their entire village. In a fascinating synthesis of indigenous and Christian ritual, the men wield bamboo canes that are used as both flutes and swords to engage one another in this fight; an electronic score by composer Mario Lavista highlights this mixing of music and violence by combining the flutes with electronic effects to create a blurry synesthetic soundscape.27 The sound also accentuates the way the film uses dissolves and double exposures to suggest a kind of mythic time.

The processing of the past through technology hints at the ways sound can seep from one epoch into another. This analogy of fluidity and cross-fertilization ties the film and exhibitions more generally to Douglas Kahn’s iconic analysis in Noise, Water, Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts. For Kahn, the ability of audio waves to transpose from one medium to another is central to understanding how sound shaped speculative thinking, especially in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, where it helped synthesize divergent fields, including physics, biology, mysticism, and science fiction.28 He argues that this permeability illustrates how sound has always been linked to radicalism and futurisms—breaching orthodoxies and fostering the intersection of noise, revolution, and the occult—themes that are central to the exhibitions. Two examples in Kahn’s book frame this history and helped me unpack the many different strands of art history at work in both shows. The first is Kahn’s discussion of Antonin Artaud, whose Theater of Cruelty (1938) was inspired, in part, by the author’s experience taking peyote with the Tarahumara people during a historic trip to Mexico in 1936 in a bid to heal himself.29 The second is William Burroughs, who characterized language as a virus. Burroughs’s pioneering “cut-up” method using audiotape is an important precursor to our digital age of contaminated files and glitch aesthetics.30 A third example is Alejandro Jodorowsky’s extravagant happenings, known as ephemerals, which took place in Mexico City in the 1960s and merged theater with installation art to create a form of “panic” in audiences in order to “enlarge the limits of consciousness.”31

These examples allude to a period in Mexico that curator and art historian Cuauhtémoc Medina has characterized as having “a social and cultural imaginaire that was becoming increasingly complex and conflictive.” This era was characterized by “Frommian psychoanalysis, post Catholic spirituality, Zen Buddhism, alchemical esoterics, and indigenous mysticism.”32 While this quote refers to the second half of the twentieth century, it echoes the heady mixing of art, psychology, and political ideology that marked the period right after the Mexican Revolution, when a similar utopian spirit sought to graft local and foreign modes into a framework for a new discursive Mexican identity. This physical and cultural intersection, based on both imperial ideologies of progress and technological innovation, is the literal melding that gives rise to the analogy of the cyborg.

Ruins and Resonance: Sound as Germ

When Madrid asks us to imagine the history of Mexico as a hybrid of the indigenous and the audio-machine, he insists we acknowledge the evidence and pervasive influence of its precolonial past. What is more, the argument foregrounds how the land and peoples of Mexico are steeped in a kind of cultural residue, an idea that points to the metaphor of sound as liquid.33 Categories in both exhibitions evoke this interstitial medium, linking past and present. In Modos, this category is Resonance, and in Constelaciones, it is Emanations. Both terms point to a shared phenomenology that I have already linked to the occult, in which “The theme of resonance [is] a principle of sympathy of bodies in vibration.”34 Again, we are asked to understand sound as constituting an affective ecology of unseen matter that is everywhere all the time, embodied both by the obvious number of historic sites across Mexico, including many within Mexico City itself, but also in and by the voices and cultural idioms that seep up from beneath the surface, perpetually destabilizing the foundation of a Mexican identity. The theme of the subterranean, alluding to both the archeological metaphor explored above and perhaps also the infectious germ of the incurable-image, per Elhaik, is the subject of several works in the show. In Tania Candiani’s Ríos antiguos, ríos entubados, ríos muertos (Ancient Rivers, piped rivers, dead rivers, 2018), at LAA, viewers can play a series of small wooden wind-up music boxes. Carved to resemble pipes, Ríos antiguos produces sounds that mimic the flow of the four rivers that once fed Lake Texcoco and that are now diverted under Mexico City.

Pablo Lopez Luz, Vista Aérea de la Ciudad de México I (Aerial View of Mexico City I), 2012. Inkjet prints, 23 x 23 in, series shown as projections in the exhibition. Courtesy of the artist.

Guillermo Galindo, Typical Secret Document, 2015. Mixed Media on double-sided cut paper, 24 x 49 1/2 in. Courtesy of the artist.

Constelaciones de la Audio-máquina en México: Ruinas y reconstrucciones de una historia sónica (Constellations of the Audio-Machine in Mexico: Ruins and Reconstructions of a Sonic Story), installation view, Museo Morelense de Arte Contemporáneo Juan Soriano, Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico, October 18, 2018-March 31, 2019. Courtesy of Carlos Prieto Acevedo.

Perhaps the most consequential way Kahn’s liquid metaphor can help frame sound as an analogy for Mexican identity is in José Vasconcelos’s ideal of a La raza cósmica (The Cosmic Race, 1925).35 Vasconcelos developed this famous image of Mexican modernism in his essay of the same name. The ideology of a mixed ethnicity grounded in an idealized past embodies the avant-garde fantasy of the cut-up as well as the resonance of “bodies and vital fluids.” These ideas form the basis of what Madrid calls “the post-revolutionary mythology of Mexican Nationalism,” in which the cosmic race is an imaginaire that mashes together adopted European polemics—promoting progress via machines, robots, technology—while also championing a nationalist evolutionary identity personified by mestizaje or miscegenation.36

In Ex Teresa, the category Sound, Textuality and Voice uses this rhetoric of a new hybrid people, which embodies a distinctly Mexican vernacular, to striking effect in projects that deconstruct language itself. Installed together in a small room, seminal literary figures, including Ulises Carrión, Octavio Paz, Xavier Icaza, and Germán List Arzubide, outline the semantic roots of sound art, especially as seen in concrete poetry. Vitally, this category reinforces the role of syntax as a tool for exegesis—characterized as much by manifestos as scores—and to the way spells and scientific formulas share a common desire to capture and embody invisible phenomena. This physical distillation of the voice can be seen in the dynamic poetry of Gonzalo Deza Méndez (1893–1967), whose Irradiador (Radiator, 1923) and La marimba en el patio (The marimba in the courtyard, 1923) seem to presage Alfred Barr’s infamous taxonomy of abstraction—its own kind of utopian archaeology. Although Mendez’s poetry was originally laid out for the page, in Modos de oír, the poems are reproduced directly on the walls as large painted murals resembling a kind of glyph.37 Mendez’s interest in how ideas manifest graphically and can communicate a notational body—or nationalist fantasy—suggests the way the estridentists deployed sound as a mode of resistance.

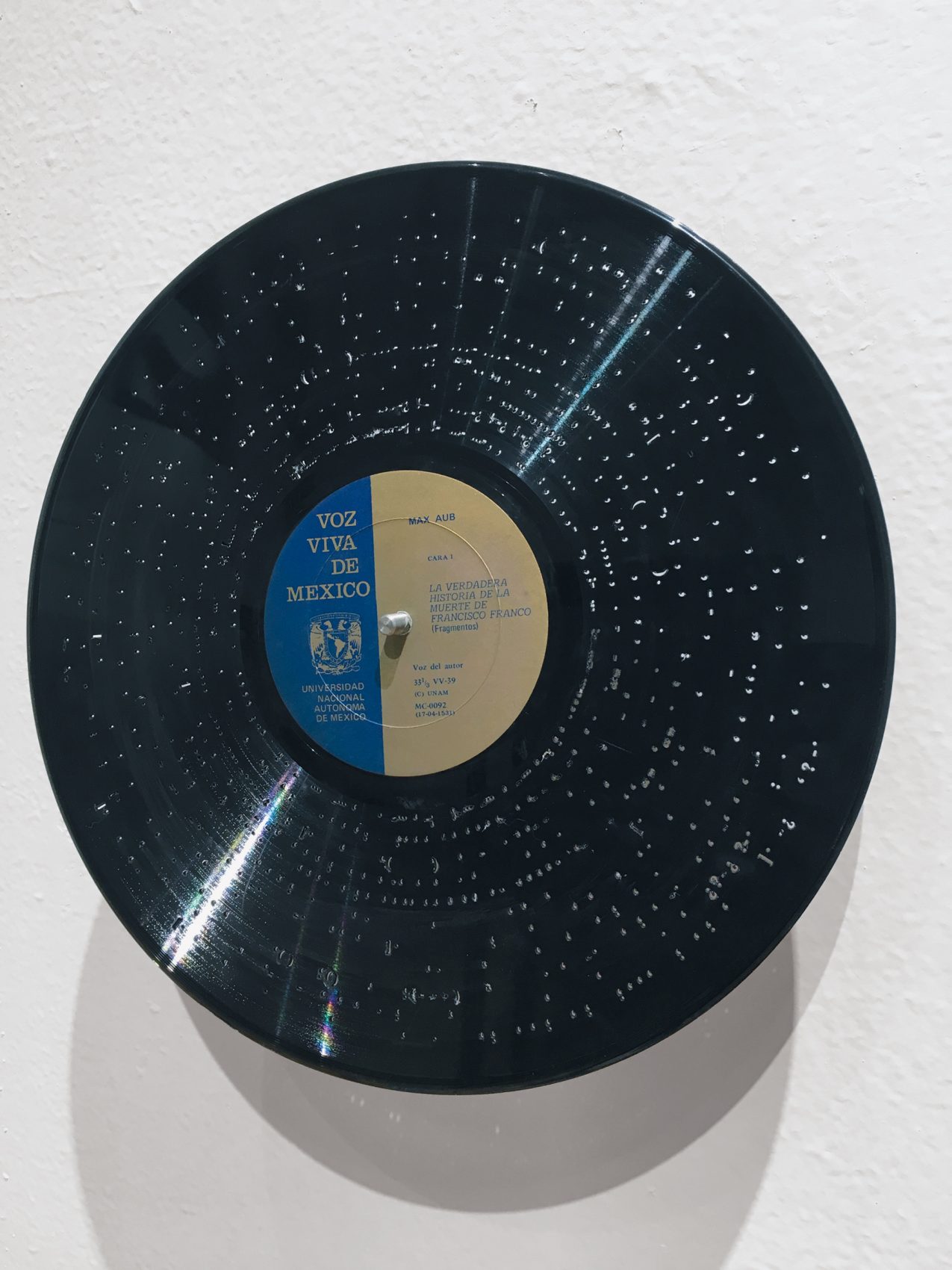

Pieces in both Ex Teresa and LAA explore this idea in tandem with other experiments in typography and notation. An LP titled The Poets Tongue (1977) illustrates the recently rediscovered work of Carrión and his early experiments in book publishing and performances. Unfortunately, the record is displayed only as an object and is not played, which is a shame because it includes a marvelous spoken-word piece titled Hamlet for Two Voices. The recording consists of two actors reading the name of each character of the eponymous play in order of appearance.38 An uncanny object by Manuel Rocha Iturbide hanging on the wall, titled Doble puntuación (Double Score, 2014), also represents this impulse to carve out or inscribe new meaning from existing forms. The wax surface of an appropriated LP, fittingly titled Voz viva de Mexico (Live Voices of Mexico), has been perforated with hand-carved punctuation marks that cover the entirety of the disc, becoming a kind of synthesis of totem and poem. A mural work by Verónica Gerber Bicecci sets a more corporeal tone while also playing with the structures of punctuation, here illustrated by thought bubbles, braces, and the cryptic title painted in the work: Los hablantes: cuerpa mas voz=escultura (The Speakers: Body Plus Voice=Sculpture, 2018). Carlos Amorales’s Anti Tropicalia (2017) also explores the way typographical marks organize written communication. In this site-specific wall work installed in LAA, Amorales uses graphite guiros (a familiar Latin percussive instrument) to draw large and complex miasma of concentric vectors that resemble both weather patterns and the parallel lines of staff paper.39 In the latter examples, notational systems seem to link directly to a legacy of European modes of hearing and pedagogy while also nodding to the persistent influence of concrete poetry. While the work alludes to the advent and dissemination of Western modes of notated music as one of many strategies colonialism employed for reifying its control structures, I wish that the whole complex and polluted corpus of this musical hegemony had been broached more directly by these artists. In my opinion, notation, while conceptually powerful, retains an aesthetic distance that makes it a somewhat tepid framework for criticism. In this case, the playful gestures, word play, and acts of defacement seem overly polite given the subject matter.

Gonzalo Deza Méndez, Irradiador, 1923/2019. Mural created from layout in the journal Irradiador. Courtesy of Ex Teresa Arte Actual. Photo: Isaac Contreras Valenzuela.

Magnavoz (2005), a video work in Ex Teresa, grapples more directly with these questions of colonial patrimony, exploring the role of technology, language, and race in Mexico’s history using the radio as an analogy for social agency and economic modernization. Director Jesse Lerner based Magnavoz on a polemic of the same name written in 1921 by Xavier Icaza. (Icaza labeled his own work a farce.) In Lerner’s script, the fictionalized voices of many of Mexico’s best known intellectuals of the time, including Vasconcelos and Diego Rivera, alongside heavyweights such as Vladimir Lenin, argue amongst themselves about what type of social praxis will, in the words of Rivera, “wake the masses from their endless slumber.” The video offers a deeply sardonic critique of Mexican idealism, including, it would seem, Icaza’s own avowed estridentism, and skewers both the Left and the Right. Magnavoz cleverly uses the disembodied but authoritative voice of the radio—personified by a silly-looking Gramophone that pops up in different scenes to deliver the competing soliloquys—to suggest how technology and mass media from outside Mexico was imported and used to aggressively promote foreign interests, often disguised as progress.40

Icaza’s prose is remarkably prescient in setting up a dialectic between native Mexican ideals and those coming from Europe and America. This work also demonstrates that in the early twentieth century, the central ideological modes of being Mexican (of hearing Mexican) already had been established: “the idealistic-mystic, the conservative-practical, the leftist-Communist, [or] the autochthonous-nationalist.”41 In addition, by pointedly exposing technology as a vehicle for latter-day colonial ideas, Icaza identifies the nascent conflict within Mexico’s modernization and how it would become the basis for an incurable-image.42

Jesse Lerner, Magnavoz, 2005. Video still. 16mm transferred to video, sound, 25:33 min. Courtesy of the artist.

The Monstrous: Sound as Leaky Totem

A great many of the works in the exhibitions evoke the theme of technology activating people or, in the words of Jodorowsky, enlarging “the limits of consciousness.” In Modos, printed signs that say pieza activa (active piece) accompany many of the pieces. These sculptures and installations engage what the curators call a “sound device” and what Constelaciones labels as the “audio-machine,” a loose designation suggesting that the art does something.43 Prieto Acevedo argues that sound’s power of metamorphosis resides within these liminal apparatuses. He evokes both a totemic argument and a more tangled logic of performativity, positing, “In our darkest hour, when the horizon of our country is filled with tragedy . . . we are inhabited by sounds that announce a transformation.”44 The category of Lo Monstruoso (The Monstrous), in Constelaciones, presents this transformation most forcibly. Here, the Monstrous is defined in terms of a phantasm, and it illuminates the way the terminology of progress has always contained a whiff of mysticism. Prieto Acevedo writes, “In this aesthetic, one can see and hear the life forces that are at once resisting and fused with the machine. As they metamorphose and abandon all ontological delimitations, these forces return to the amorphous state of the body and to the matrix of survival.”45 While this strikes me as an example of the curator engaging in some speculative, even sci-fi rumination, I can’t help but note how it describes literally the eschatological fantasy of sound as herald, wherein noise marks an abandonment of “all ontological delimitations” and, one assumes, some kind of apotheosis. I also think this hints at one of sound art’s pervasive problems, wherein it relies too much on the theatrical power of the invisible and the exotic shock of the unfamiliar, the loud, the atonal. This complex interface highlights how ways of listening are based largely on the sonic interface between listener and source—a physical dynamic and process of orientation that I raised at the outset of this review when discussing the aural dynamics of the hovering helicopter.

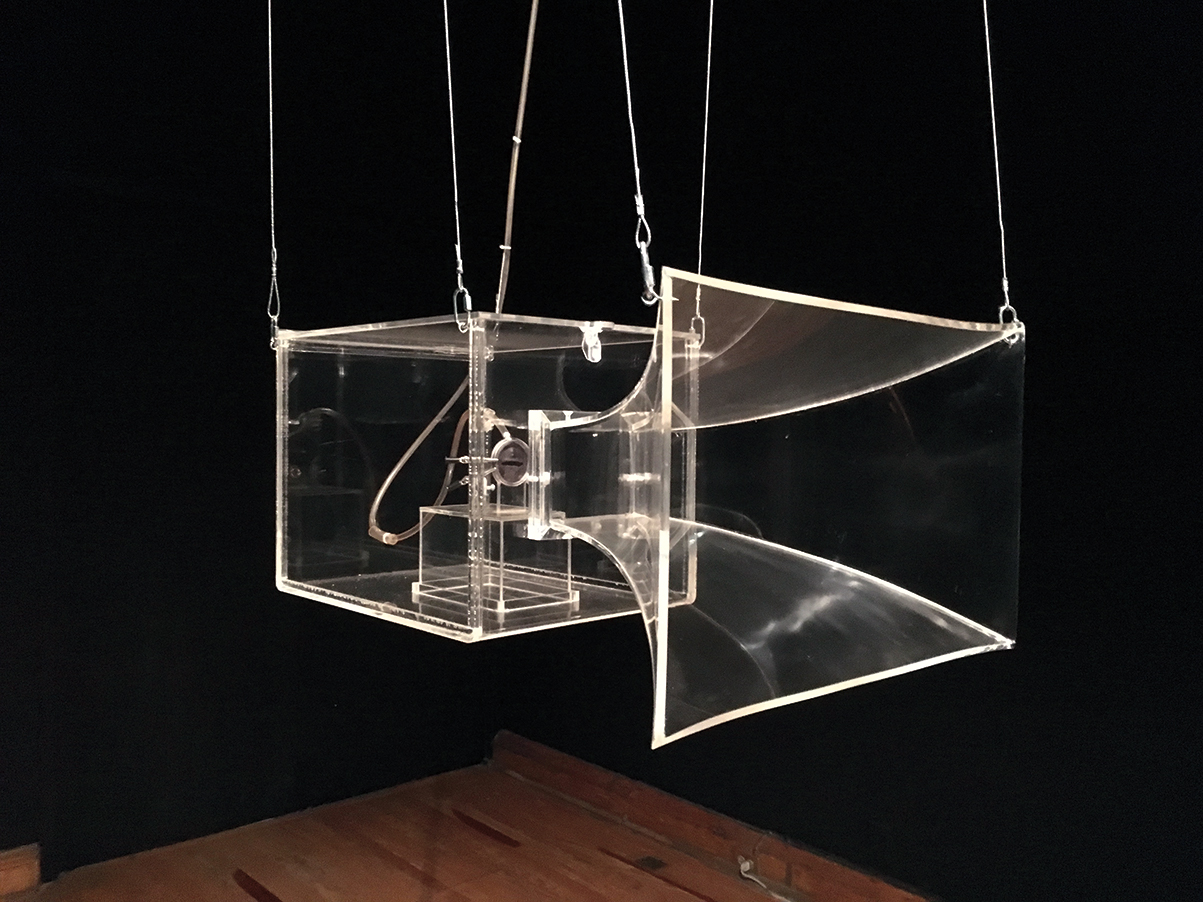

While Constelaciones puts forth the theme of the monstrous, it is most powerfully manifest in a work in Modos: Gustavo Artigas’s Sirena (Siren, 2007), which is classified in LAA under the category Sculpture and Sound Objects. Sirena is a replica of a civil defense siren constructed entirely of clear plexiglass. Within its center are the taxidermied vocal cords of a dead man (as described in the checklist). Activated with a continuous stream of air pumped from outside through a thin tube, the apparatus emits an endless, discomfortingly high-pitched shriek that balances horror with a kind of annunciation à la Attali. Sirena also might be understood in light of Elhaik’s conception of the incurable-image as fugo, which translates as both the musical term for fugue and as leakage (as in a gas or water leak).46

This evocation of a leak is compelling. While the curators of both exhibitions clearly want to frame their exhibitions as sweeping introductions to and analyses of the twentieth century, the inherent mutability of sound—especially vis-a-vis technology—as a kind of ghost in the machine seems anathema to curation. Indeed, much of what is radical about noise is inevitably tied to this subject of the invisible or the uncanny and how sound can manifest otherwise inexplicable phenomena through decay, drone, feedback, and static. It is precisely this chaotic milieu that generates occult thinking and spawns fantasies of a cyborg as a means of transcending the laws of physics and marshaling unseen forces. I wish that this more existential conflict, linking curating to post-nationalism and post-humanism more generally, had been better articulated in the exhibitions.47 One of my complaints throughout both shows, but most notably in Modos, is that not only did the curators not write any texts designed to frame the historical breadth and critical context of their exhibition, but also none of the curators in either show cites authors who might allow for a more extended and robust inquiry or even an introduction for the audience.48

Instead, the exhibits leave sound art to continuously recycle a quantum fantasy in which a molecular approach promises to make evident in greater and more granular detail the mysteries of the universe. The challenge of transducing energy of all kinds, be it spiritual or electromagnetic, is central to this quandary, which links politics and ontology with technology. This is the same context in which Luigi Russolo, the Italian author of The Art of Noises (1913) and one of the founders of Futurism, created his own instruments, called intonarumori, which occupied an intersection of sculpture, engineering, and ritual performance. A seminal figure in sound art, Russolo’s project was based on “the idea that mat- ter is constituted by condensation of waves vibrating at different intensities.”49

Gustavo Artigas, Sirena (Siren), 2008. Plexiglas, dead man’s vocal cords, air pump. Installation view, Modos de oír: prácticas de arte y sonido en México (Ways to Hear: Art and Sound Practices in Mexico)< Laboratorio Arte Alameda, Mexico City, November 29, 2018-March 31, 2019. Courtesy of Laboratorio Arte Alameda.

The intonarumori exemplify the modern noise synthesizer as sculptural object as diviner as healing device, and it influenced many contemporary artists working today. Indeed, I would argue intonarumori are the archetypal sound objects, providing the conceptual blueprint for most sound artworks, and examples of this genre abound in both Modos de oír and Constelaciones. Fernando Vigueras’s Traslaciones III (Translations III, 2017) is a complex kinetic installation consisting of amplified guitars and violins that allows viewers to adjust the speed of specialized belts in order to play and alter their pitch in a real-time cyborg duet (LAA). Guillermo Galindo’s small stringed instrument assemblage MAIZ-Cybertotemic (2006) resembles a cross between a totem and a robot (Constelaciones). An installation by Minerva Cuevas (LAA) features a playback machine, albeit unplayable, titled The Battle of Kalliope (2004). It juxtaposes an obsolete music box with a photograph of smiling NATO officials cutting a cake and a notated score for the German melody Ich weiss ein Herz (I Know a Heart) with the rhythmic sound of a ritual Vodun (voodoo) curse being placed on the government of George W. Bush.50 Her sculptural arrangement, which resembles an altar or an incantatory spell, pointedly reveals the way the object as instrument still traffics in occult potential. Similarly, Galindo made his MAIZ-Cybertotemic “after exploring Native American and Mesoamerican cultures and reading Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Psychomagic which is about curing with personal objects.”51 In a related vein, Juanjosé Rivas’s ensemble composition M: Mascullar (M: Mumble, 2018), a variable length piece performed live at Ex Teresa during one of their public programs, is a percussive work played on “prepared” horse mandibles. This deeply strange and affecting piece foregrounds the ways humans can use innovative instrumentation to merge with other species via sound.52

Never Lost: Noise as Life

Even on the poorest streets people could be heard laughing. Some of these streets were completely dark, like black holes, and the laughter that came from who knows where was the only sign, the only beacon that kept residents and strangers from getting lost.

—Roberto Bolaño53

Manuel Rocha Iturbide, Doble puntuación (Double Score), 2014. Altered LP record. Courtesy of the artist and Ex Teresa Arte Actual. Photo: Gerardo Sanchez.

The title for this review was inspired by the artist list for Modos de oír found in the curatorial statement. After introducing many of the more than one hundred artists included in the show, the list ends with “among others.”54 For me this evoked not only the impossible ambition of the exhibitions—which can’t even accommodate all of the artists’ names!—but also, if inadvertently, that sound is a medium that exists between things, connecting them, among them. In this way, the caveat inadvertently touched on the critical imperative of both exhibitions—navigating post-nationalist identity—and made its most salient point: sound art is indefinable and uncontainable. This is true especially in a place as dynamic and culturally rich but economically poor and politically unstable as Mexico, where, as argued by many of the Mexican artists I spoke with, and echoing Elhaik, noise retains its power to amplify a person’s complex and incurable life—thereby forming a last line of resistance against the many remaining vectors of cultural colonization, caste, and censorship. Taken as a whole, Modos de oír and Constelaciones de la Audio-máquina en México spoke to this power of sound to channel political and spiritual energy and hinted at the ongoing importance of sound art in Mexico. More generally, and away from the specifics of Mexican sound art, both exhibitions affirmed my gut feeling that sound is the most important creative medium, not only of the twentieth century, but also of the twenty-first.55 This opinion is founded, in part, on the view explored in both exhibitions that the power of sound resides in its unique ability to announce the invisible and the liquid. Sound is vital because it celebrates the interstitial and challenges the catastrophic segregation and bias of both racism and anthropocentrism. Sound connects all living things in a way no other medium can.

Nick Herman is an artist and writer in Los Angeles.