“Happenings were what you call new dance today.”

Simone Forti1

The moon landing took place on my fourth birthday–July 20, 1969. Utopian Viennese architectural team Haus-Rucker-Co. (Laurids Ortner, Klaus Pinter, Günter Zamp Kelp) created an Environment/Happening Mondessen (Moonfood) in the center of Vienna. I remember being interested in a giant piece of cake as high as a three-story building. There were some see-through helium-filled pillows flying towards the moon. The local TV station broadcast the whole event, which included me holding one of those helium-filled, heart-shaped pillows. My grandmother in Tyrol saw me on TV and nearly fainted. TV was not that common back in those days. I remember a second project, Live, that Haus-Rucker-Co. did in 1970. It was a big room filled with a giant inflatable mattress and several clear balloons. Like the bounce-houses now commonplace at the birthday parties of American children, visitors were invited to climb in and jump. The kids loved it, of course, and none of us ever forgot it.

I neither knew nor cared that I had been part of a copy or a spin-off of a Happening. The term “Happening” had long been separated from its original art context, disconnected from what Allan Kaprow meant by his “intentional Happenings” and “Environments,” which he started making in the 1950s. For Kaprow, these terms carried specific meanings and instructions. By the 1970s, Kaprow abandoned the term “Happening” in the face of its generalized popularity, using instead the more neutral “Activity” or “Timepiece.” In the dictionary the noun “happening” is defined as (a) an event or occurrence (as in: altogether it was an eerie happening) or a noteworthy or exciting event (as in: an all-star, superstar, megastar happening); as well as (b) a partly improvised or spontaneous piece of theatrical or other artistic performance, typically involving audience participation (as in: a multimedia happening). As an adjective, it is described as “fashionable, trendy (informal),” (as in: nightclubs for the young are the happening thing). Happenings have become youth-consumer items, crowd pleasers that underwent a further transformation in the 1990s, becoming cool “free parties,” places of youth culture in Berlin and Vienna, very efficient at linking kids to Coca Cola, Nike and yuppie culture. In the U.S., the legacy of happenings might include raves and Burning Man.

However, I would still consider my Haus-Rucker-Co. experience an extension of a Kaprowesque Happening, because I was part of it. A Happening works with collective memory—its reality exists in the genuine and often physical experience had by the participant. Happenings also have an educational element, because you can show your child the documentation in her or his photo album later and say, “See, this was a Happening, an art piece, and you were in it!” The act of conveying the term “Happening” from one generation to another could also be considered a Happening in itself, not unlike my telling you of my experience at age 4 with Haus-Rucker-Co.’s Happening here in these pages.

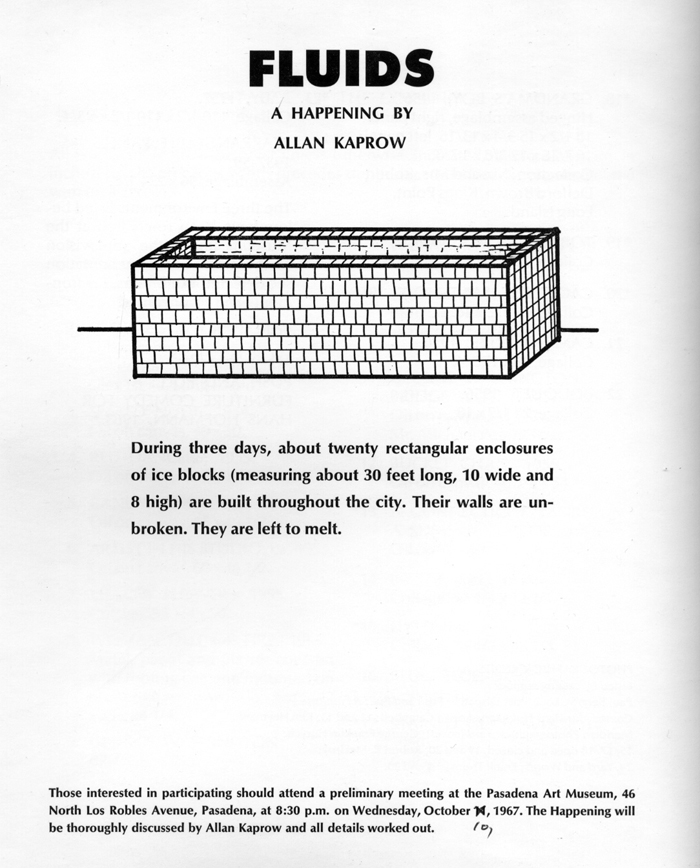

As I write this, Happenings are being enacted all over Los Angeles in association with Allan Kaprow: Art as Life on view at MOCA through June 2008. These Happenings are like bacteria. They are hard to grasp. I wonder if anyone out there has seen all of them. I imagine the chance encounters people are having with these events, experienced without a framework to buttress them as art. Do they get infected? Does it register as art, or history? Does it matter? And just what is a Happening today? If you know a little, this bacterial type of Happening leaves you with the bitter taste in your mouth—like you missed out on something. Kaprow’s Happenings took place at a certain moment, in a certain context. What do they mean as activities now? Or, as the artist Zach Rockhill said after reeinventing Fluids at Performa 07 in New York, the Happening “deepened an already vexing question about doing a performance/happening/event that has already occurred: where on the spectrum of participation and authorship does a ‘reinvention’ lie?”2

I too wonder where Fluids lies within this particular set of questions. For those of you who missed it, the original Fluids (1967) was commissioned by the Pasadena Art Museum and consisted of building large, ice-block enclosures in fifteen locations around L.A. in late summer. If you Google “Fluids” you find many, various reinventions or reenactments of Fluids, such as those in New York at Performa 07 and in Italy. In its recent manifestation, Fluids was installed in several places in L.A. I was at one such installation with my two-year old daughter. It was hot and she did not want to leave. She was sitting on a block of ice and whenever we tried to depart, she screamed, “NO ICEE ME!” We took a picture—more than one—of course. In time we will show them to her, and tell her that she too has been part of a Happening. Will it matter that it was a reenactment, or as the Kaprow estate prefers, reinvention? I find the process of recreating and extending history within collective memory through a reinvention and a re-telling of the art history of Happenings works compelling as I encounter these events around the city.3 Twenty-two different Happenings infected L.A. in many locations at many different times. Fluids was here and there around town; Publicity was at Vasquez Rocks, Trading Dirt at the Watts Towers, Claremont Graduate School and Avenue 50 Studio. I don’t know how much history made it through the infection, but we must let it run its course.

I was particularly drawn to the reinvention 18 Happenings in 6 Parts at Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE ). This piece had a kind of trashiness, a kind of updated junk aesthetic about it. I was attracted by its simplicity, by the canvas walls covered with plastic to indicate walls and room dividers and, to me, its framework of reenactment. Even though the original 18 Happenings in 6 Parts at the Reuben Gallery in New York in 1959 mostly relied on scripts and rehearsals, Kaprow evidently left space in the score for more happenstance interpretation. At the beginning, we in the audience received a program with a letter addressed to Mr. Kaprow from Steve Roden, who organized the LACE event. The letter gives you an idea of the humor that lies in the impossibility of being able to recreate the pieces in their original form. ”We wished you had left us a better roadmap, but we figured it would be easy enough to build one ourselves. …We struggled a lot with the concept of reconstruction…” The letter deals with the inability to recreate 18 Happenings in 6 Parts and comes to the conclusion that Kaprow had already been aware of this impossibility at the time…and that he is now smiling about it.

18 Happening in 6 Parts is a complex chess set of scored movements for both performers and audience that took place at LACE over five nights. The instructions in the original and the reenacted piece call for cards to be handed out to the audience. Three types were distributed. “Be seated as they instruct you.” This directive was followed by the rules concerning when and where to move. “Take a seat in room one.” “Take a seat in room two.” “Take a seat in room three.” Following Kaprow’s original score, Roden assembled an impressive ensemble of artist performers, all of whom in one way or another had either known Kaprow, or had an influence on the history of performance art in their own right. At LACE , the program notes listed who they were and what actions they were to perform. Some were seated in the audience and these I especially enjoyed watching. Paul McCarthy began the evening as a member of the audience, became a performer, and then an orange squeezer. If you’ve ever seen one his performances, you may recall that he has a very specific way of squeezing oranges. And if you look at the original photos of 18 Happenings from 1959, you will see a very intellectual looking performer, Rosalyn Montague, elegantly squeezing oranges. My three cards kept me in room one throughout the evening, but Paul McCarthy’s cards let him move from one room to another. He ended up squeezing oranges in his special way in a different room while I stayed behind and was only able to get a hint of what was going on elsewhere… Damn!

Among the other performers, all of whom are part of my collective memory of the history of performance art, was Simone Forti, an artist deeply involved in the revolution of modern dance that took place around the legendary Judson Studios. At one point, I saw Forti moving on all fours through part of the room on pieces of wood. I could not help but think of her performances of animal movements and her Dance Reports, one of which reads:

So go I over here and put my self over here and then I put my self over there, A rock here over there and by it another and another, A rock there and over there here a rock, And over there a rock and next to it and others and there and there and there...4

The relevant metaphor here is probably not bacteria, but rather Deleuze and Guattari’s rhizome, where the historical, personal, sensory and eccentric associations a participant might have break up and recombine in all sorts of lively ways. The (re)enactments of Happenings work for me as long as they occur in public spaces that confer the potential for this kind of surprising new life. They don’t work inside the deadening space of a museum retrospective, and the MOCA presentation of Allan Kaprow: Art as Life did nothing to change my mind. Organized by the Haus der Kunst, München, in cooperation with the Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, this traveling show was realized at the Geffen Contemporary in one long gallery. Along one wall hung Kaprow’s early paintings and collages; along the opposite wall were fifteen tables displaying documents with many of his original scores and notes in vitrines. There were several overhead projectors aimed at the wall with a shuffle pack of transparencies, mostly documentation of the original Happenings—a weak nod toward both audience participation and school lectures. In the center, occupying most of the space of the gallery, several artists who had worked with or were affiliated with Kaprow, such as John Baldessari and Skylar Haskard, Allen Ruppersberg, Barbara T. Smith, Paul McCarthy, and Suzanne Lacy with Peter Kirby and Michael Rotundi invented or reinvented four interactive Kaprow Environments. These pieces felt like crowd-pleasers, a sop to a kind of anxiety that I am certain was neither the intention of the artists nor the curators. It was as if presenting the documentation of the Happenings and Environments with the early paintings and collages was insufficiently sexy, tactile or immediate. The inclusion of these remade Environments, dominating the space and literally pushing Kaprow’s actual works to the perimeters of the exhibition, felt to me like a plea: “Dear Audience, Please experience a Happening now.” What worked so well with the Happenings going on around the city is exactly what failed here. I would not mind these pieces if they could be given the life of a contemporary effort, but not inside the cocoon of the museum, where they can only be homages to something that happened long ago and far away.

The contradiction and the question here lie within the institution itself: can a Happening be institutionalized if it was never intended to be institutionalized? At the exhibition, I observed that the audience and guards were involved in a very complicated dance. In the confused and confusing space were interactive Kaprow Environments, that invited participation, Kaprow paintings that you should not touch, and videos that you should sit and respectfully watch. Could the guards at MOC A chasing the audience, the audience chasing the guards, the instructions to “touch,” “not to touch,” “to participate,” and “to anticipate” be an extension of reinventing Kaprow Happenings?

In thinking about the current wave of reenactments, I am interested in Kaprow’s work from the 1990s—a period in which he appropriated his own artwork. He reimagined seven Environments, each of which, when presented by the commissioning Fondazione Mudima in Milan, was accompanied by a mural-size photograph of its original occurrence. Jeff Kelley describes the recreations this way: “Kaprow seemed to acknowledge the profound global and cultural changes of the previous three decades…by smoothing out his materials and consolidating his metaphors. …For instance, …bohemian street junk was replaced by synthetic material and standardized easily consumable units….”5 Kelley says of Yard (1961/1991), “In Milan, the famous photograph of the youthful Kaprow throwing a tire in the sculpture garden of the Martha Jackson Gallery drew a striking contrast with its 1991 version, in which a silly, tireless Fiat…was surrounded not by a stormy black sea of used American rubber, but by a hot-pink wall with racks of smaller new Italian tires organized in neat, bureaucratic rows.”6 In Milan, visitors were invited to change the tires, not throw them around. Kelley reads this as a metaphor for the body’s aging process, which is one interpretation particularly available to Kelley, a friend, former student and long time biographer of Kaprow.7 However, considerably less romantic interpretations are possible here as well, for example relating to labor, efficiency, organization, and complicated technology. Has Kaprow reenacted his own art history in this work or has he simply juxtaposed old thoughts with his current positions, thereby producing something new, or at the very least an evaluation of past versus present achievements?

I wonder why no greater thought was put into including this period of his work at the MOC A show, in order to offer reflection, through Kaprow’s own example, on what appropriation and enactment might mean today. Kaprow confronted the reinventions himself, reconfiguring his works through some alchemical meld of the documents and intangible memories and insights of his own that none of us now have. In rethinking the document and the Happening, I would like to argue that this is the missed opportunity of the Kaprow retrospective: the consideration of Kaprow’s documents as performance pieces themselves. Phillip Auslander argues in The Performativity of Performance Documentation, “the act of documenting an event as a performance is what constitutes it as such [sic].”8

To conclude, I turn to Phillip Auslander’s insight into precisely this issue of documentation and performance:

“The more radical possibility is that [the Happenings] may not even depend on whether the event actually happened. It may well be that our sense of the presence, power, and authenticity of these pieces derives not from treating the document as an indexical access point to a past event but from perceiving the document itself as a performance that directly reflects an artist’s aesthetic project or sensibility and for which we are the present audience.”9

One of the most revealing things in Steve Roden’s letter to Kaprow is the conclusion reached by the LACE reinventors to not document their performance on video. As I understand it, they felt the productive tension between the score and the original documentation from 1959 made the creative space for a reinvention possible. They refused to muddy up the historical waters for those who, in the future, will need to reinvent Kaprow for themselves.

Carola Dertnig lives and works in Vienna and was a participant in the 1997 Whitney Museum Independent Study Program in New York. She is a Professor for Performance Art at the University of Fine Arts in Vienna and is currently visiting in the Photography and Media program at CalArts. Dertnig’s work has appeared at P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center, Artists Space, Museum of Modern Art, New York, and the Secession in Vienna. She is the author with Stephanie Siebold of Let’s Twist Again (If You Can’t Think It, Dance It): Performance in Vienna from 1960 until Today, D.E.A Buch und Kunstverlag (Vienna), 2006.