All Access Politics: Reality and Spectatorship in Two Film Installations by Jean-Luc Godard and Hito Steyerl1

For there is a rule and an exception. Culture is the rule, and art is the exception. Everybody speaks the rule: cigarette, computer, T-shirt, tourism, war. Nobody speaks the exception. It isn’t spoken, it’s written: Flaubert, Dostoyevski. It’s composed: Gershwin, Mozart. It’s painted: Cézanne, Vermeer. It’s filmed: Antonioni, Vigo. Or it’s lived, and then it’s the art of living: Srebrenica, Mostar, Sarajevo. The rule is to want the death of the exception.

—Jean-Luc Godard, Je vous salue, Sarajevo (1993)

The commentary from Jean-Luc Godard’s 1993 short film Je vous salue, Sarajevo (Hail, Sarajevo), unambiguously positions art as part of the enlightenment tradition: in the face of culture’s oppressive quotidian normativity, art is seen as an agent for social change. Mozart’s spirited concertos, Vermeer’s cinematic depth, Flaubert’s unromantic prose, and the works of other historical figures are evoked alongside locales of violent siege and genocide during the Bosnian War. The film serially frames elements of a journalistic image showing carnage and armed forces in the former Yugoslavia. A steely portrait of two brutes is confronted by a shot of a clutched rifle, then a grainy detail of an ashen cigarette. Later, we see the faceless bodies of citizens lying against a slick, stony sidewalk. Godard cuts between such details before ultimately pivoting to an expanded frame, these disparate shots combine to form a total image. The collaging of these details, figured as breaks within a totalizing whole, underscores not only a central editing strategy in the filmmaker’s later work, but also his faith in film’s capacity to stir critical observation and knowledge production. If art is the exception to (mass) culture’s rule, how does such an “exception” become integrated, or create a new form of social ordering?

Contemporary film installations—not unlike film itself—can be seen as straddling concomitantly mass cultural and avant-garde projects, but their generally self-conscious approach toward a particularly embodied, affective visual engagement further complicates the moving image’s unstable history with dialectical thought. Often such productions take editing strategies founded on cutting and joining visual components and expand these approaches by augmenting the role of sound and lighting, along with employing sculpture and architecture to reorder visual signals and reconfigure spectatorship. In the 1930s, Walter Benjamin argued that cinema was an artistic mass form that sidestepped the rarefying forces produced by singular, original works of art. As art became reproducible and broadly representable to exhibition audiences across geographies, its aura waned. Today, there has been a reversal of this process.2 Indeed, the film installation’s deployment within the museum can be viewed as the institutional reintegration of aura. The moving image, when articulated through totalizing audiovisual environments, becomes both less mobile than previous plastic arts were in comparison to film, and also less accessible than today’s digital video formats, which users can readily stream thanks to mobile computing. The film installation also accommodates a subject Rosalind Krauss describes, in a different context, as being “in search not of affect but intensities, the subject who experiences fragmentation as euphoria, the subject whose field of experience is no longer history, but space itself.”3 Though Krauss’s argument was made in reference to minimalism’s visual register (one of a bodily immediacy) operating within grandiloquent museum spaces, a similar affective response still applies. Thus bodies, space, and objects are here incorporated into the trajectory of the moving image—all within an institutional frame directed toward a public.

In her 2009 essay “Is a Museum a Factory?” Hito Steyerl addresses the shift of political cinema into the museum space, stressing that the white cube can be a site for contestation equal to the so-called reality outside it that political film attempts to reshape. She highlights a remark Godard made to a group of young artist filmmakers at Le Fresnoy-Studio working with film installations. Godard warned them against the inclusion of technical apparatuses accompanying the filmic frame, saying that the objects comprising their installations didn’t contribute to an explanation of reality and cautioned the pupils “not to be afraid of the real.”4 Steyerl argues to invert Godard’s logic, proposing that the museum’s bourgeois interior, with its “blank horror and emptiness,” is also the “Real with a capital R.”5 In her view, the real is both staged and produced by the valorized art object through a process of contesting and corroborating representation. For Godard, reality is located not only outside the filmic frame and the museum space, but also outside the site of cultural production. Indeed, the real we should not fear is beyond the camera, preceding representation. It is sited in the space of capture: war-torn Sarajevo, massacred Srebrenica, a street corner, the flick of a cigarette. In their work, Godard and Steyerl reveal fundamental differences in their conceptions of critique and image politics, which are elucidated both through these opposing concepts of reality and their attitudes toward the spectator as receiver of critique.

Je vous salue, Sarajevo was one of many short films that appeared in Godard’s notorious 2006 exhibition Voyage(s) en utopie, Jean-Luc Godard 1946–2006: à la recherché d’un theorem perdu (Travel(s) in utopia, Jean-Luc Godard 1946–2006: In Search of a Lost Theorem), at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. The work looped on a tiny iPod screen placed within a shabby maquette, which detailed one of Godard’s original proposals for the exhibition. Voyage(s) en utopie was arranged as a three-room installation of films and objects in varying states of destruction, but its manifestation—and evolution—inhabited public consciousness well before its institutional debut. Prior to its mounting, a public narrative had already unfolded between the filmmaker and his partnering institution, which accounted for impossibly ambitious programming plans, artistic disagreements, depleted $1M budgets, six-month delays, and the firing of the exhibition’s curator. It is likely that the destructive conflict was actively engineered by Godard as a kind of crisis that would nourish his artistic output while congealing a metanarrative of the myopic institution curtailing his artistic agency.6

Voyage(s) en utopie, Jean-Luc Godard 1946–2006. Installation view, Centre Pompidou, Paris, May 11 – August 14, 2006. Image courtesy of Centre Pompidou, Mnam/Cci-Bibliotheque Kandinsky, JP Planchet.

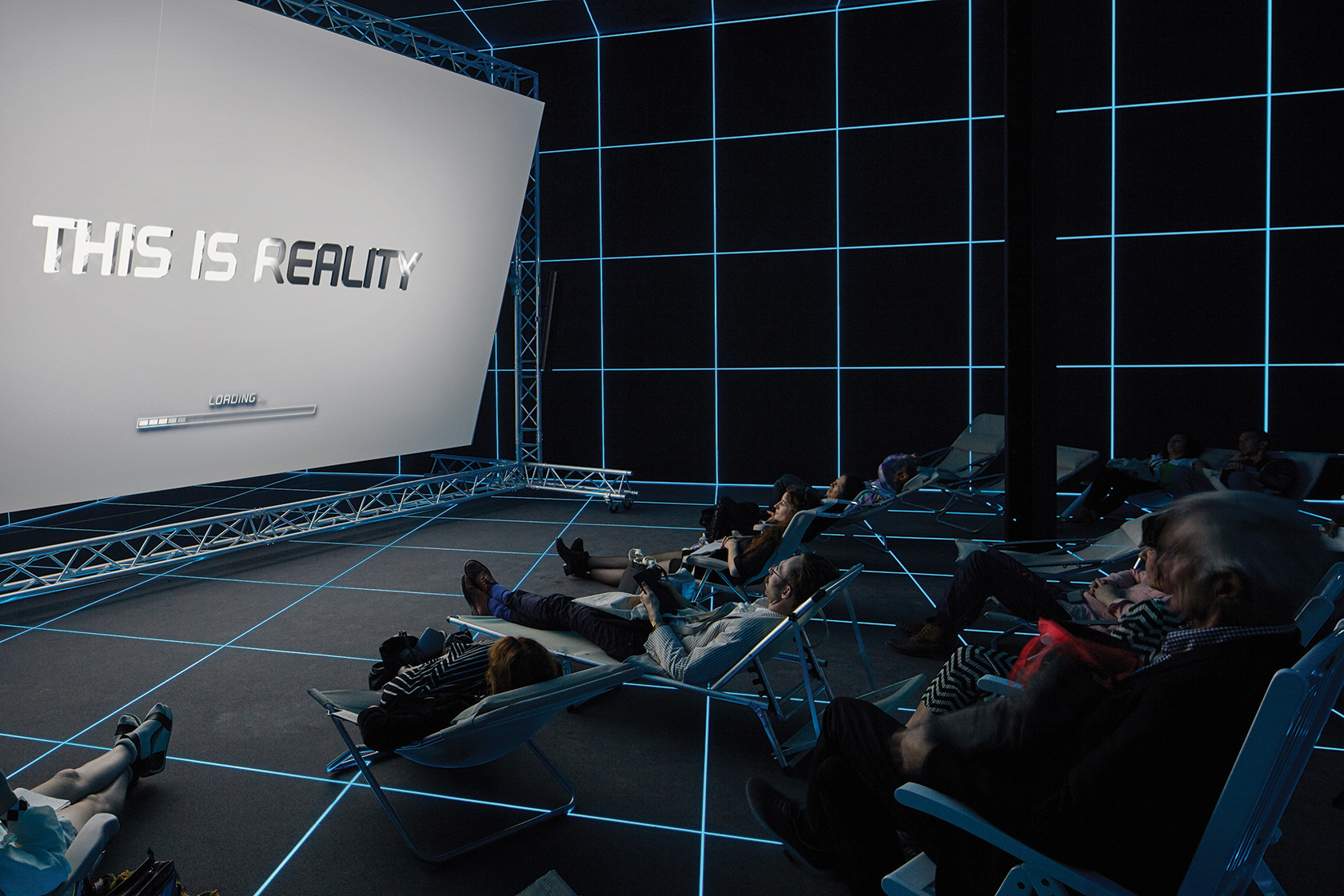

In Hito Steyerl’s 2015 film installation Factory of the Sun, a massive projection screen enclosed in a slick metal truss system peers down upon its viewers.7 The display construction is configured diagonally to the room’s enclosing architecture, which, with its darkened interior, connects to traditional variations of screening film. However, Steyerl’s installation is less a black box than a framework for representing immersive new worlds. The viewing space, gridded by cyan LED strips, configures itself as an allegorical motion capture studio (in the spirit of Star Trek’s holodecks) wherein the agency of bodily movement is recorded and transmitted to generate renderings of environments and political scenarios. Yulia, one of the film’s protagonists, narrates that Factory of the Sun is a dystopic video game in which users begin as forced laborers confined to the motion capture studio, where every movement is captured and converted to sunshine. Her disembodied, robotic voice speaks over whirling, gleaming metallic 3-D rendered text that reads: THIS IS NOT A GAME—THIS IS REALITY. For Steyerl, reality is deployed primarily through mediation: a world of images and avatars, one that is introduced by a loading progress bar. It is comprehended and disputed through media, within digital realms of combat and scoring, all of which shape the construction of human desire and perception. And it is precisely through encountering such an immense, complex rendering of artifice that one can accord the historically privileged status of “reality” to a space of otherwise representation. The real of the viewer is thus subordinate to this melodrama, positioned as a conduit that finds its entry sited in the installation/capture studio.8

Hito Steyerl, Factory of the Sun, 201 5. Installation view, Venice Biennale, German Pavilion, May 9–November 22, 201 5. Courtesy of the artist and Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York. Photo: Manuel Reinartz.

All of this aligns with Steyerl’s elaboration of “proxy politics,” her position that the political unfolds today between avatars, bots, or shadowy organizations that stand in for people or groups as agents.9 Agency, in the case of Factory of the Sun, is manifest as the data transmitted and ultimately rendered by one’s recorded movements within the scenarios circumscribed by the namesake video game. The film’s ending is hacked and interrupted by a typewritten “Bot manifesto,” calling for resistance to “total capture,” and that “all politics are proxy politics.” Today, with remotely operated drone warfare commonplace, it’s not difficult to imagine Steyerl’s argument concretely applied. But if this is indeed the case, how within the realm of the proxy do we account for human death—the kind that can’t be re-spawned in the form of new avatars? Where does one locate the suffering inflicted by miscalculated drone fire, or any form of political violence? The norm given to Factory of the Sun circumscribes reality to a complex array of renderings, indicators, and signs, wherein any notion of an “outside”—a break from mediation—is situated within the very installation space that, as a locus of encampment, serves to produces these signals. Norms, as Judith Butler observes, are “enacted through visual and narrative frames” that in their formation imply a level of decisive exclusion.10 This polarity begs for us to examine not only that which is seen and unseen, marked and unmarked but also that which vacillates between these frames’ borders. In Steyerl’s case, the dialectic between the frame and its outside is transformed into a synaptic link. The installation is mimetically subservient to the narrative of the filmic frame; in effect, the frame eclipses the installation. To recall Butler, “The image, which is supposed to deliver reality, in fact withdraws reality from perception.”11 Pressuring this, one could argue further that the museum space, spectacularly fashioned as a motion capture studio and inclusive of a film riddled with metanarratives, registers itself as a kind of image.12 And within this image, the representation of space (that of the viewer) is formulated according to the narratives playing out on the screen—a representation of the represented.

If Steyerl’s deployment of “reality” is toward a collapse of the real with the images and representational structures that powerfully mediate our understandings of it—a process within which there appears no outside text—one could think of Godard’s strategy as a collision between film and the real, a negotiation between representations of reality and the reality of representation. In Voyage(s) en utopie, one saw a glaring difference in film’s very treatment: it was nearly everywhere across monitors and handheld devices, and yet made feeble in stature and diffused across a number of historical practices and periods. For Godard, if the moving image was meant to break through the real, here the artist seemed to position the real itself as a victim of violent montage in the museum, with film acting as a museum prop at its side. AV equipment climbed up and around walls of uneven sheetrock, meandering in jumbled circuits. Dense foliage from houseplants in temporary pots crowded together, inhabiting the second room; in the exhibition’s final chamber, Godard’s life size mock-up of a blandly habitable contemporary domestic space appeared to be deliberately as forgettable in the museum space as it is ubiquitous outside of it. A slick HD monitor awkwardly wallowed as yet another horizontal surface in the kitchen corner as it played clips of pornography. Across the room, another monitor rested upright—aloof and alert, at the head of an impoverished double bed—and screened Ridley Scott’s 2001 big-budget Black Hawk Down. John Kelsey writes, “Godard travesties aesthetic strategies that no longer produce images of the world, that do nothing but blindly reproduce the sameness of museums or bedrooms (and the subjectivities that inhabit them).”13

Voyage(s) en utopie, Jean-Luc Godard 1946–2006. Installation view, Centre Pompidou, Paris, May 11– August 14, 2006. Image courtesy of Centre Pompidou, Mnam/Cci-Bibliotheque Kandinsky, JP Planchet.

If capitalism occurs at its most functional on the day-to-day level of the real, Godard stresses this force by presenting all of these quotidian objects together; in their sameness they represent the conditioning of desire (sexual, domestic, and affective) into something readymade. Butler’s emphasis on framing and its “outside” are pertinent, as here Godard gestures as if to frame that which is typically too banal to be captured (the quotidian norm) all the while leaving it in ruins. Reality appeared to percolate everywhere in Voyage(s) en utopie, itself an amalgam of many parts belonging outside the museum, shown as barely functional or visually exhausted. Any façade of completion or polish was either overtly avoided or undone across the installation. On institutional signage, marks from a Sharpie pen slashed the stated “technical and financial differences” that rendered Godard’s original proposal impossible; only one stated difference remained unblemished: the “artistic.” Holes were smashed between the rooms of “Yesterday” and “The Day Before Yesterday.” A model train, surrounded by wooden fence posts, circled through the openings. On the train’s tracks was adhered a quote by Sartre: “A dialectical thought is first of all, in the same movement, the examination of a reality in terms of it being the part of a whole, in terms of it negating this whole, in terms of the whole containing it, conditioning it and negating it.”14

Voyage(s) en utopie, Jean-Luc Godard 1 946–2006. Installation view, Centre Pompidou, Paris, May 11 – August 1 4, 2006. Image courtesy of Centre Pompidou, Mnam/Cci-Bibliotheque Kandinsky, JP Planchet.

Sartre’s tripartite dynamic is operative here in the way Godard treats the objects installed in the museum space. Steyerl made an apt characterization by calling the museum’s “reality” one of “blank horror and emptiness.” If anything, Godard appears to take this schema as a point of departure. But there is no capital R in this space of the real—all that is capitalized (and capitalist) is, to recall Sartre: retreated, worked through, and negated.

A viewer’s actions, or activity, are often decisive traits of film installations, and again, between these two artists, we see their configuration of spectatorial activity in radical opposition. Viewers of Factory of the Sun assume the position of more or less traditional spectators of cinema. Reclining white lawn chairs are bestrewn across the installation’s motion capture chamber, and individuals can lean supine to behold the immense radiance of the work’s broad projection screen. During a recent conversation at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, Steyerl remarked about how the German Pavilion’s fascist architecture represented to her an “almost churchlike structure to inspire awe, to overwhelm people,” and that this process of feeling overwhelmed was something she desired to produce within the context of the information age.15 Is the process of being overwhelmed necessarily an indicator of passivity or of mediation? Factory of the Sun enacts the pavilion’s historically totalizing architecture to produce a kind of contemporary media fascism, one that references a condition totally enveloped by technical apparatus to the extent that what is recognized as artifice might as well be called “reality,” given its lived effects. In comments on the “myth of activity” for spectators of contemporary film installations, Erika Balsom asserts how the binary notion of the passive cinema spectator and the active gallery visitor is rooted in a tenuous conflation of physical stasis with “regressive mystification” and physical ambulation with criticality.16 Any strict determinism between an exhibition’s architecture and the spectator’s criticality precludes an evaluation of the gallery space’s ideological determinations. And, considering how discourses concerning power have shifted from locating centralized nodes to elucidating flexible, broadened networks of control, the very acts of circulation and participation are “by no means activities of resistance, but in fact precisely what is demanded of us in the experience economy.”17 Indeed, though spectators in Factory of the Sun are configured to static viewer positions, their passivity has less to do with their physical orientation than the thematic and ideological environment enclosing them. By employing sundeck chairs, Steyerl’s proclivity toward kitsch becomes a kind of sculptural pun, whereby viewers are invited to perform the act of relaxation under the screen’s radiating white light, while simultaneously flatly gesturing to a rephrased Donna Haraway quote heralded during the film’s opening sequence: “Our machines are made of pure sunlight.”18

Hito Steyerl, Factory of the Sun, 2015. Video stills. Single channel high definition video, environment, luminescent LE grid, beach chairs. 23 minutes. Image CC 4.0 Hito Steyerl. Courtesy of the artist and Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York.

Can relaxation be prescribed? What interest might Steyerl’s project have in maintaining a passive crowd? Steyerl’s writings also draw allusions to Jacques Rancière, whose conception of the spectator as group raises concerns similar to Steyerl’s own work. The narrative in Factory of the Sun allegorizes the audience as a group of laborers, which parallels Steyerl’s position that cinematic politics today produces a crowd rather than educates it. Such post-representational politics “replace the gaze of the bourgeois sovereign spectator of the white cube with the incomplete, obscured, fractured, and overwhelmed vision of the spectator-as-laborer.”19 For Steyerl, the gaze of this multitude is distinctly not collective but rather “distracted and singular.”20 Rancière positions the spectator as an individual entity amidst a group that is specifically not a community but rather a kind of mosaic. The power of this group is not by a linked collectivity but rather an amassing of individual perceptions.21 Such an assessment is directly compatible with a work such as Factory of the Sun, wherein the spectator is identified as the participant of a metaphorical single-player video game. But what does individual translation and perception matter within the auspices of such a totalizing sensorial apparatus, the precise purpose of which is to produce affect? Steyerl’s spectator occupies a realm within which the gap between performers on the stage and spectators in theater—between overwhelming spectacle and passive consumer—are rejected. The body in the reclining sun chair is leveled with the role-playing avatar projected on the screen, all of which perform under the guidelines set out in the film’s narrative.

Visitors ambulating through Godard’s Voyage(s) en utopie faced a qualitative difference in relation to film and its presentation. Along with being able to move through multiple arrangements across tangible space, spectators encountered film through dozens of gleaming backlit displays. The vast selection of clips on view were made possible by the fact that such moving images were presented on screens suited for the individual consumer. Seven films by Godard, some with his longtime collaborator Anne-Marie Miéville, were sequenced on portable-sized LCD panels that were visible through gaudy frames or holes in sheetrock. Godard’s detailed maquettes teetered nearby in piles, decorated with dollhouse-like furniture, printed clippings of paintings, and mobile phones screening short films. These intricate, diminutive dioramas, along with the compact wall-mounted LCD displays, often precluded viewership to a singular body. If Steyerl places the spectator within a hazy collective of individuals linked through experience, Godard here rejects such a conceptual pairing, stressing how display technology and hegemonic ideology have produced alienated individuals, beholding and consuming images in isolation. Notably, he stresses this formulation having worked through various historical iterations of spectatorship accompanying cinema’s display, from the projector and black box to the TV set and now the mobile computer.

Hito Steyerl, Factory of the Sun, 2015. Installation view, Venice Biennale, German Pavilion, May 9–November 22, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York. Photo: Manuel Reinartz.

Godard’s installation further troubles spectatorship by rejecting the museum’s direct relation to its audience. The institution’s status as seamless host, as a site of production for historical truth and cultural value, was ruptured by signage informing visitors the installation is one of compromise and conflict—a collaboration brought to its knees by “artistic, technical, and financial difficulties,” the latter two factors being crossed out by Godard’s acrid permanent marker. This particular notice reappeared elsewhere in the halls of the installation, along with the artist’s corrective ink. Such intervening marks engaged a kind of piercing rhythm to the work, as the spectator saw as much the arrangement of film, digital displays, and tawdry, mundane groupings as their defacement, rearrangement, and destruction. The marker’s inscription, a kind of camera-sharpie along the lines of Alexandre Astruc, amended written tenses, it circumscribed visitor movement and knowledge, and to a broader extent served as synecdoche for Godard’s critical voice—one that is punny, intervening, and often establishes itself as a possessor of truth in the face of institutional power.22 In exercising his critical position, Godard insists on showing his audience how “things are not as they seem to be.” Has this clear-eyed, critical view of the system—sited within the museum—become an element of the system itself?23 To what extent does Godard’s tirelessly corrective mark, his displacement of film and television across myriad exiguous sites of viewing, and his violent collaging of museum space and quotidian objects—in other words, his valorized position of the critic—set up a rhetorical contradiction that produces the spectator as disenlightened and lacking the artist’s valuable knowledge, which itself is given a kind of currency? And how does my own position as critic accept and extend such a dynamic?

Voyage(s) en utopie, Jean-Luc Godard, 1946–2006. Installation view, Centre Pompidou, Paris, May – August 14, 2006. Image courtesy of Centre Pompidou, Mnam/Cci-Bibliotheque Kandinsky, JP Planchet.

Reintroducing Godard’s commentary in Je vous salue, Sarajevo delineates a stark contrast between it and Steyerl’s corresponding model of spectatorship and politics. By figuring art as an exception to the rule of mass culture, Godard holds out belief that art’s capability for social transformation is as ontologically inherent as it is continually threatened. By reshaping such a belief as a false offer corresponding to its own hegemonic structure, Steyerl’s project undercuts the potential for dialectical rupture, in turn reconfiguring critique itself as totality. While a case against the self-superior enlightened critic may be an attractive one, it’s uncertain how such a position renders the dynamics of knowledge production as anything but a standstill. To the extent that Godard and Steyerl each accommodate critique for their own ends, it is clear that such political modes point toward radically dissimilar understandings of reality. For Steyerl, to construct a representation of such immense and complex artifice, and to call it reality, gives a clearer, more precise glimpse of the real. In turn, reality is produced not only in the realm of the museum, but specifically in the space of the film studio, where movements are captured and rendered. Such a space of capture, where the camera records, is also where Godard locates the real, but in his case this environment is distinctly outside the studio or the museum. For him, these latter spaces are where representations of reality are violently clipped, stilled, countered, and reassembled into an allegory of social transformation. Given these differences, where do we locate art as an exception to reality? Is this so-called real any different from the one that we encounter in the museum? If the ultimate goal of representation is to reshape the real, our challenge vis à vis reality is less to confront a fear of it and more to reposition our distance from and access to it.

Nicolas Linnert is a critic and art historian based in New York.